The medical specialisation model in Spain is carried out in the context of specialised health training, through the residency programme. The aim of the study is to analyse, by an anonymous survey, the opinion on three aspects among final-year residents in Endocrinology and Nutrition (E&N): self-assessment of the knowledge acquired, working prospects, care and training consequences arising from the pandemic COVID-19.

Materials and methodsCross-sectional observational study using a voluntary and anonymous online survey, shared among final-year national interns in the last year of the E&N programme, carried out between June–July 2021.

Results51 responses were obtained, 66% of the fourth-year residents. Overall perception of their knowledge was 7.8 out of 10. Most external rotations were in thyroid and nutrition areas. A total of 96.1% residents, carried out some activity associated with COVID-19, with a training deterioration of 6.9 out of 10. 88.2% cancelled their rotations and 74.5% extended their working schedule. The average negative emotional impact was 7.3 out of 10. 80.4% would like to continue in their training hospital, remaining 45.1%. 56.7% have an employment contract of less than 6 months, most of them practising Endocrinology.

ConclusionThe perception of the knowledge acquired during the training period is a “B”. Residents consider that the pandemic has led to a worsening of their training, generating a negative emotional impact. Employment outlook after completing the residency can be summarised as: temporality, practice of Endocrinology and interhospital mobility.

El modelo de especialización médica en España se realiza a través de la formación sanitaria especializada, mediante el sistema médico interno residente (MIR). El objetivo del estudio es analizar, con una encuesta anónima, la percepción de tres aspectos entre los MIR de último año de Endocrinología y Nutrición (EyN): autoevaluación de conocimientos adquiridos, futuro laboral, consecuencias asistenciales y formativas derivadas de la pandemia COVID-19.

Materiales y métodosEstudio observacional transversal tipo encuesta online, voluntaria y anónima, distribuida entre los MIR de último año de EyN a nivel nacional, realizada en junio y julio de 2021.

ResultadosSe han obtenido 51 respuestas, el 66% de los MIR de cuarto año. La percepción global de sus conocimientos es 7,8 sobre 10. La mayoría de las rotaciones externas han sido en las áreas de tiroides y nutrición. El 96,1% de los residentes han desarrollado alguna actividad relacionada con la pandemia, con un deterioro formativo calificado de 6,9 sobre 10. El 88,2% han cancelado sus rotaciones, ampliando su jornada laboral el 74,5%. Un 80,4% querrían continuar trabajando en el hospital donde se han formado, siguiendo un 45,1%. El 56,7% tienen un contrato inferior a 6 meses, ejerciendo mayoritariamente Endocrinología.

ConclusiónLa percepción de los conocimientos adquiridos durante la formación es de un notable. Los residentes consideran que la pandemia ha supuesto un empeoramiento formativo generando un impacto emocional negativo. La perspectiva laboral tras finalizar la residencia se resume en temporalidad, ejercicio de Endocrinología y movilidad interhospitalaria.

The current configuration of specialised health training [formación sanitaria especializada] (FSE) in Spain is carried out by means of the internal resident physician system, better known as MIR [médico interno residente]. This method of learning was imported from the United States, where it was introduced in the late 19th century, reaching Spain in the 1960s. Since 1984, this system has constituted the only legal route to gaining access to medical specialisation, after completing four or five years of training, depending on the course chosen. The MIR contract is a dual model, with its working and training conditions defined in Spanish Royal Decree (RD) 1146/2006 and RD 183/2008, respectively. Therefore, the resident stage entails a number of years that involve working to learn. This involves external rotations in different departments and training areas, not forgetting the research facet.

This structure has been consolidated for decades, allowing residents to acquire the skills and knowledge that guarantee a high qualification, giving the system a great reputation. By means of an annual resolution, the Spanish Ministry of Health approves the offer of places and conducts a tender with selective tests for access to places for the degree in Medicine. As it has evolved, various modifications have been introduced with proposals for improvement in order to adapt to the needs of the present day. The specialisation of Endocrinology and Nutrition (E&N) is defined in RD 127/1984, as the branch of Medicine that deals with the study of the physiology and pathology of the endocrine system, as well as the metabolism of nutritional substances and the pathological consequences derived from their abnormalities. Four years of MIR training is required to qualify as an E&N specialist. The educational programme and pathway is regulated according to the published Order SCO/3122/2006 approved by the Ministry of Health.1

Three surveys were administered to residents across Spain to assess training in 2000,2 20053 and 2011.4 This last publication concluded that, despite the change in the academic programme compared to the previous one in 2005, the rotations have hardly undergone any changes. In addition, the perception among residents of the training they receive from the centre and medical specialists had improved significantly compared to previous reports. In terms of specialties, working groups have been formed to find out about the situation in Spanish hospitals, with findings published in 20015 and 2008.6 These results revealed that E&N is one of the specialties at the forefront of those offered. The median number of students looking to secure places has varied little, although it has been increasing with each tender (median in MIR10 of 1404 vs MIR20 2662). This is probably influenced by the increase in the number of places offered, from 74 in MIR10 to 89 in MIR20.

Despite the previously mentioned strengths of the system, over the last few decades the National Health System has been threatened by various factors, such as budget cuts, work overload and the consequences of the COVID-19 crisis. All of this has accentuated regional differences in access to healthcare. The pandemic created a health emergency situation, decreeing a state of alarm and the need to adopt extraordinary measures in order to minimise the damage. With regard to residents in their last year of training, RD 463/2020 approved an extension in hiring with suspension of rotations in progress or that were scheduled, with the possibility of being transferred from the autonomous community if necessary. This crisis paralysed ordinary activity, with a large proportion of staff devoted to the care of COVID-19 patients, emergencies and minimising care for non-preferential conditions. For this reason, resident evaluations were postponed, and their integration into the workforce was put back until the end of September 2020 and until July 2021 for the new residents.7

The main objective of this study was to learn the opinions of professionals across Spain who did the MIR tender in E&N in 2016 (fourth-year residents when completing the survey, current first-year specialists) regarding three areas: consequences arising from the COVID-19 crisis; training aspects of the residency; and job prospects as a first-year specialist.

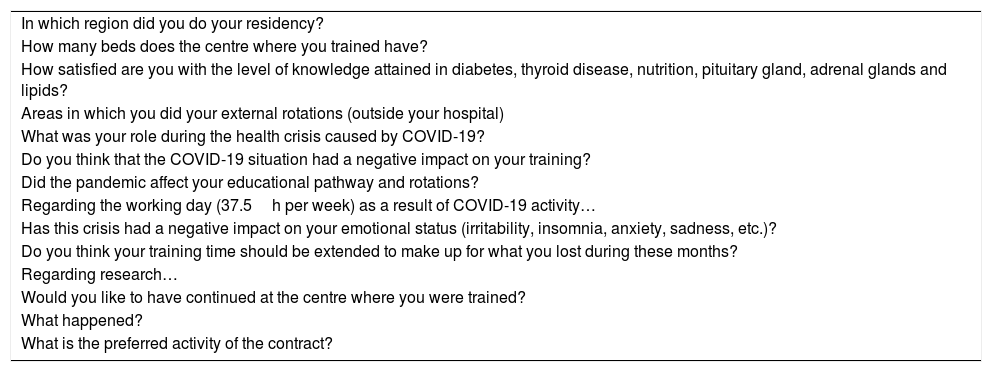

Material and methodsThis was a descriptive observational study that used a survey containing 20 multiple-choice questions (Table 1). An anonymous and voluntary form was created, using the open online platform Google Drive®. It was distributed among all residents nationwide who did the MIR tender in 2016, with instant messaging and email used to disseminate the survey. Information was collected between 02/06/2021 and 09/07/2021, although the questions refer to activity since the start of the pandemic. The estimated target population was 77 people, according to the places offered as reported in the Official Gazette of Spain (order SSI/1461/2016) for access in 2017.8

Heading of the questions asked in the survey.

| In which region did you do your residency? |

| How many beds does the centre where you trained have? |

| How satisfied are you with the level of knowledge attained in diabetes, thyroid disease, nutrition, pituitary gland, adrenal glands and lipids? |

| Areas in which you did your external rotations (outside your hospital) |

| What was your role during the health crisis caused by COVID-19? |

| Do you think that the COVID-19 situation had a negative impact on your training? |

| Did the pandemic affect your educational pathway and rotations? |

| Regarding the working day (37.5h per week) as a result of COVID-19 activity… |

| Has this crisis had a negative impact on your emotional status (irritability, insomnia, anxiety, sadness, etc.)? |

| Do you think your training time should be extended to make up for what you lost during these months? |

| Regarding research… |

| Would you like to have continued at the centre where you were trained? |

| What happened? |

| What is the preferred activity of the contract? |

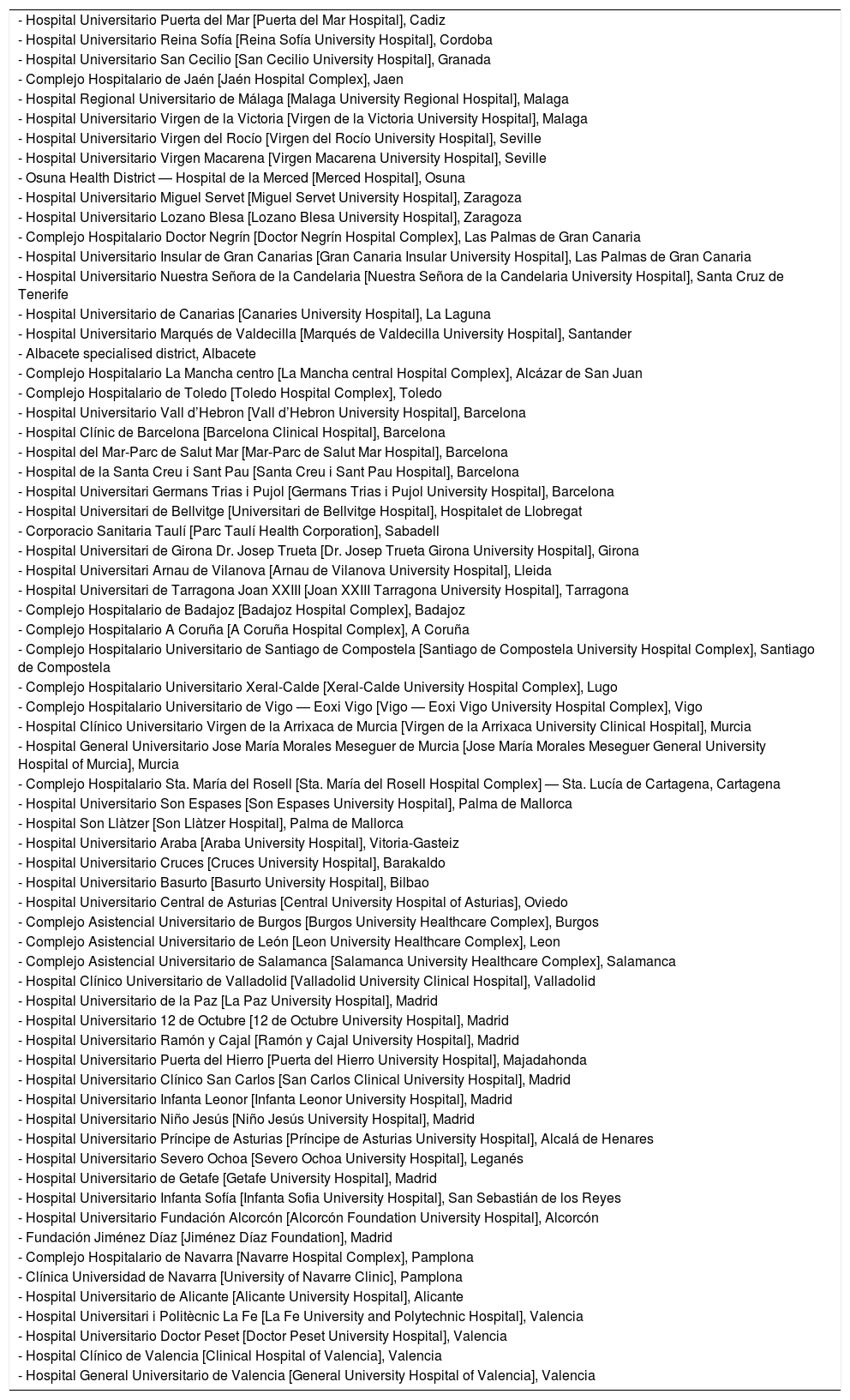

The centres to which the residents to whom the survey was distributed belong are detailed in Table 2.

Centres to which the residents to whom the survey was distributed belong.

| - Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar [Puerta del Mar Hospital], Cadiz |

| - Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía [Reina Sofía University Hospital], Cordoba |

| - Hospital Universitario San Cecilio [San Cecilio University Hospital], Granada |

| - Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén [Jaén Hospital Complex], Jaen |

| - Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga [Malaga University Regional Hospital], Malaga |

| - Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria [Virgen de la Victoria University Hospital], Malaga |

| - Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío [Virgen del Rocío University Hospital], Seville |

| - Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena [Virgen Macarena University Hospital], Seville |

| - Osuna Health District — Hospital de la Merced [Merced Hospital], Osuna |

| - Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet [Miguel Servet University Hospital], Zaragoza |

| - Hospital Universitario Lozano Blesa [Lozano Blesa University Hospital], Zaragoza |

| - Complejo Hospitalario Doctor Negrín [Doctor Negrín Hospital Complex], Las Palmas de Gran Canaria |

| - Hospital Universitario Insular de Gran Canarias [Gran Canaria Insular University Hospital], Las Palmas de Gran Canaria |

| - Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria [Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria University Hospital], Santa Cruz de Tenerife |

| - Hospital Universitario de Canarias [Canaries University Hospital], La Laguna |

| - Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla [Marqués de Valdecilla University Hospital], Santander |

| - Albacete specialised district, Albacete |

| - Complejo Hospitalario La Mancha centro [La Mancha central Hospital Complex], Alcázar de San Juan |

| - Complejo Hospitalario de Toledo [Toledo Hospital Complex], Toledo |

| - Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron [Vall d’Hebron University Hospital], Barcelona |

| - Hospital Clínic de Barcelona [Barcelona Clinical Hospital], Barcelona |

| - Hospital del Mar-Parc de Salut Mar [Mar-Parc de Salut Mar Hospital], Barcelona |

| - Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau [Santa Creu i Sant Pau Hospital], Barcelona |

| - Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol [Germans Trias i Pujol University Hospital], Barcelona |

| - Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge [Universitari de Bellvitge Hospital], Hospitalet de Llobregat |

| - Corporacio Sanitaria Taulí [Parc Taulí Health Corporation], Sabadell |

| - Hospital Universitari de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta [Dr. Josep Trueta Girona University Hospital], Girona |

| - Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova [Arnau de Vilanova University Hospital], Lleida |

| - Hospital Universitari de Tarragona Joan XXIII [Joan XXIII Tarragona University Hospital], Tarragona |

| - Complejo Hospitalario de Badajoz [Badajoz Hospital Complex], Badajoz |

| - Complejo Hospitalario A Coruña [A Coruña Hospital Complex], A Coruña |

| - Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago de Compostela [Santiago de Compostela University Hospital Complex], Santiago de Compostela |

| - Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Xeral-Calde [Xeral-Calde University Hospital Complex], Lugo |

| - Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo — Eoxi Vigo [Vigo — Eoxi Vigo University Hospital Complex], Vigo |

| - Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca de Murcia [Virgen de la Arrixaca University Clinical Hospital], Murcia |

| - Hospital General Universitario Jose María Morales Meseguer de Murcia [Jose María Morales Meseguer General University Hospital of Murcia], Murcia |

| - Complejo Hospitalario Sta. María del Rosell [Sta. María del Rosell Hospital Complex] — Sta. Lucía de Cartagena, Cartagena |

| - Hospital Universitario Son Espases [Son Espases University Hospital], Palma de Mallorca |

| - Hospital Son Llàtzer [Son Llàtzer Hospital], Palma de Mallorca |

| - Hospital Universitario Araba [Araba University Hospital], Vitoria-Gasteiz |

| - Hospital Universitario Cruces [Cruces University Hospital], Barakaldo |

| - Hospital Universitario Basurto [Basurto University Hospital], Bilbao |

| - Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias [Central University Hospital of Asturias], Oviedo |

| - Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Burgos [Burgos University Healthcare Complex], Burgos |

| - Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León [Leon University Healthcare Complex], Leon |

| - Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca [Salamanca University Healthcare Complex], Salamanca |

| - Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid [Valladolid University Clinical Hospital], Valladolid |

| - Hospital Universitario de la Paz [La Paz University Hospital], Madrid |

| - Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre [12 de Octubre University Hospital], Madrid |

| - Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal [Ramón y Cajal University Hospital], Madrid |

| - Hospital Universitario Puerta del Hierro [Puerta del Hierro University Hospital], Majadahonda |

| - Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos [San Carlos Clinical University Hospital], Madrid |

| - Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor [Infanta Leonor University Hospital], Madrid |

| - Hospital Universitario Niño Jesús [Niño Jesús University Hospital], Madrid |

| - Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias [Príncipe de Asturias University Hospital], Alcalá de Henares |

| - Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa [Severo Ochoa University Hospital], Leganés |

| - Hospital Universitario de Getafe [Getafe University Hospital], Madrid |

| - Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía [Infanta Sofia University Hospital], San Sebastián de los Reyes |

| - Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón [Alcorcón Foundation University Hospital], Alcorcón |

| - Fundación Jiménez Díaz [Jiménez Díaz Foundation], Madrid |

| - Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra [Navarre Hospital Complex], Pamplona |

| - Clínica Universidad de Navarra [University of Navarre Clinic], Pamplona |

| - Hospital Universitario de Alicante [Alicante University Hospital], Alicante |

| - Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe [La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital], Valencia |

| - Hospital Universitario Doctor Peset [Doctor Peset University Hospital], Valencia |

| - Hospital Clínico de Valencia [Clinical Hospital of Valencia], Valencia |

| - Hospital General Universitario de Valencia [General University Hospital of Valencia], Valencia |

The blocks of questions were arranged in three sections:

–Training aspects (10 questions).

–Related to the crisis arising from COVID-19 (6 questions).

–Future career (4 questions).

The study complies with the ethical principles established in the World Medical Association (WMA) Declaration of Helsinki,9 the guideline for Good Clinical Practice and the European Data Protection Regulation (EU 2016/679).10 Qualitative variables are described by absolute and relative frequencies (percentage) of their categories with a 95% confidence interval. The differences in the self-assessment of knowledge acquired were analysed using the Student’s t-test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. For the statistical analysis, the IBM SPSS Statistics v25 (Armonk, NY, USA.) program was used. Data such as age and gender were not specified in the survey, so they have not been taken into account for the statistical analysis.

ResultsA total of 51 completed surveys were analysed, representing 66.2% of the sample. The questions and their associated results are detailed below.

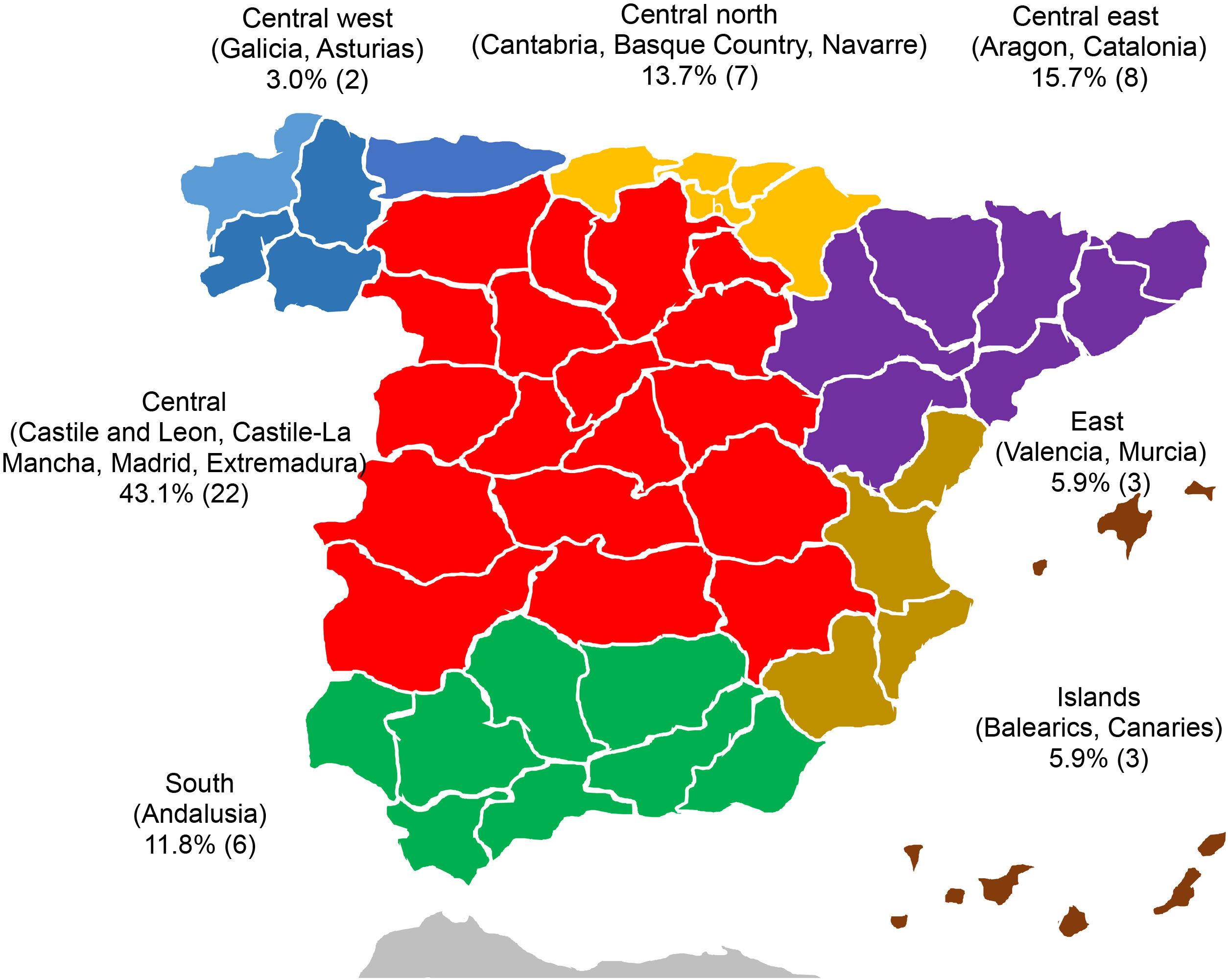

Fig. 1 specifies the geographical distribution of the place of residency of the MIRs (question 1).

In total, 41.2% (21) completed their residency in a secondary hospital (200–800 beds), compared to 58.8% (30) in a tertiary hospital (more than 800 beds).

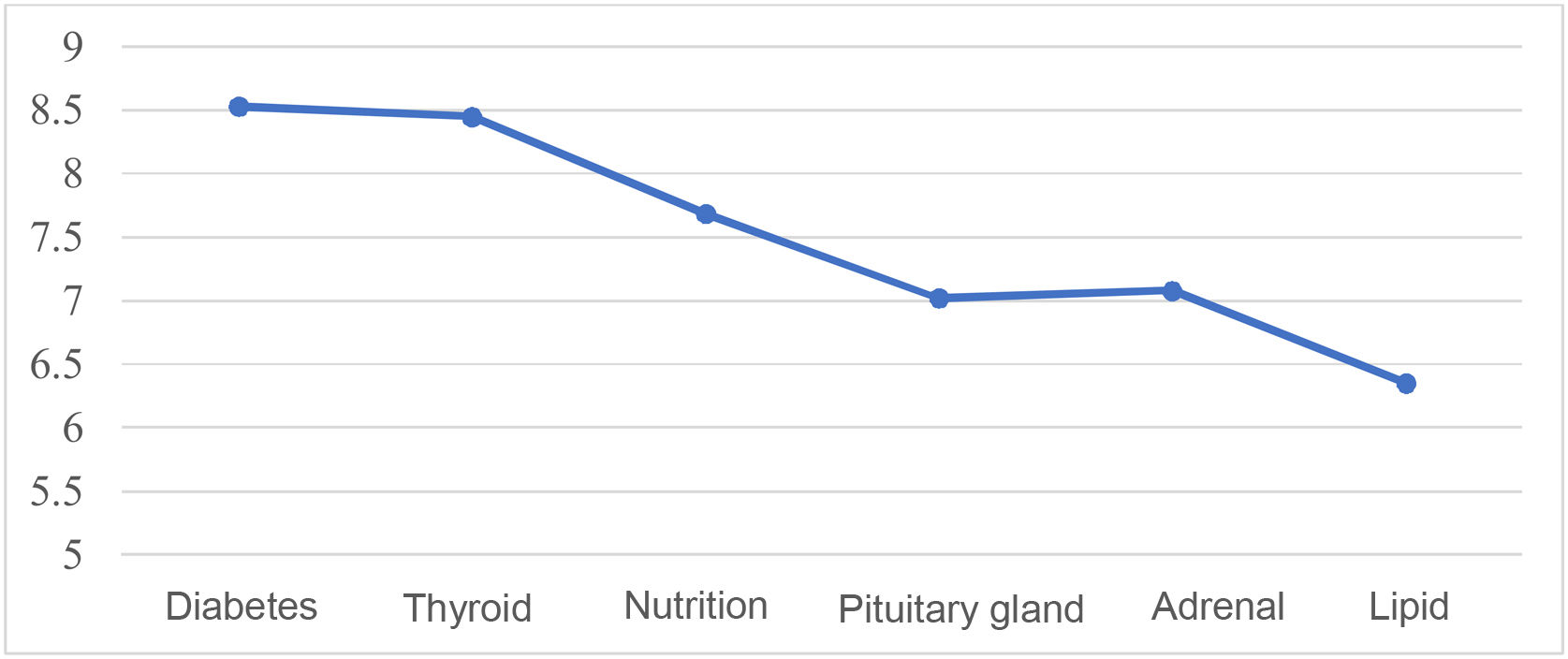

Fig. 2 shows the self-assessed average score of the knowledge acquired by the MIRs in the six areas under investigation (questions 3–8).

Question 9. Areas in which you did your external rotations (outside your hospital)The areas in which most residents did their rotations are the following: a total of 20 in thyroid disease (ultrasound, FNA, etc.), followed by nutrition with 17, diabetes (new technologies, gestational) and pituitary gland tied at 11, followed by paediatric endocrinology with five residents having done rotations, four in gender dysphoria and one in adrenal disorders, the lipid unit and neuroendocrine tumours. A total of four residents were not able to do external rotations due to the pandemic.

Question 10. What was your role during the health crisis caused by COVID-19?Most (80.4%, 41 people) were working in the COVID-19 area (hospital, ICU, emergency department, etc.), while 15.7% (8) provided indirect support without direct contact with COVID-19 patients (data collection, phone calls), compared to 3.9% (2) who continued in the E&N department without performing to COVID-19-related activities.

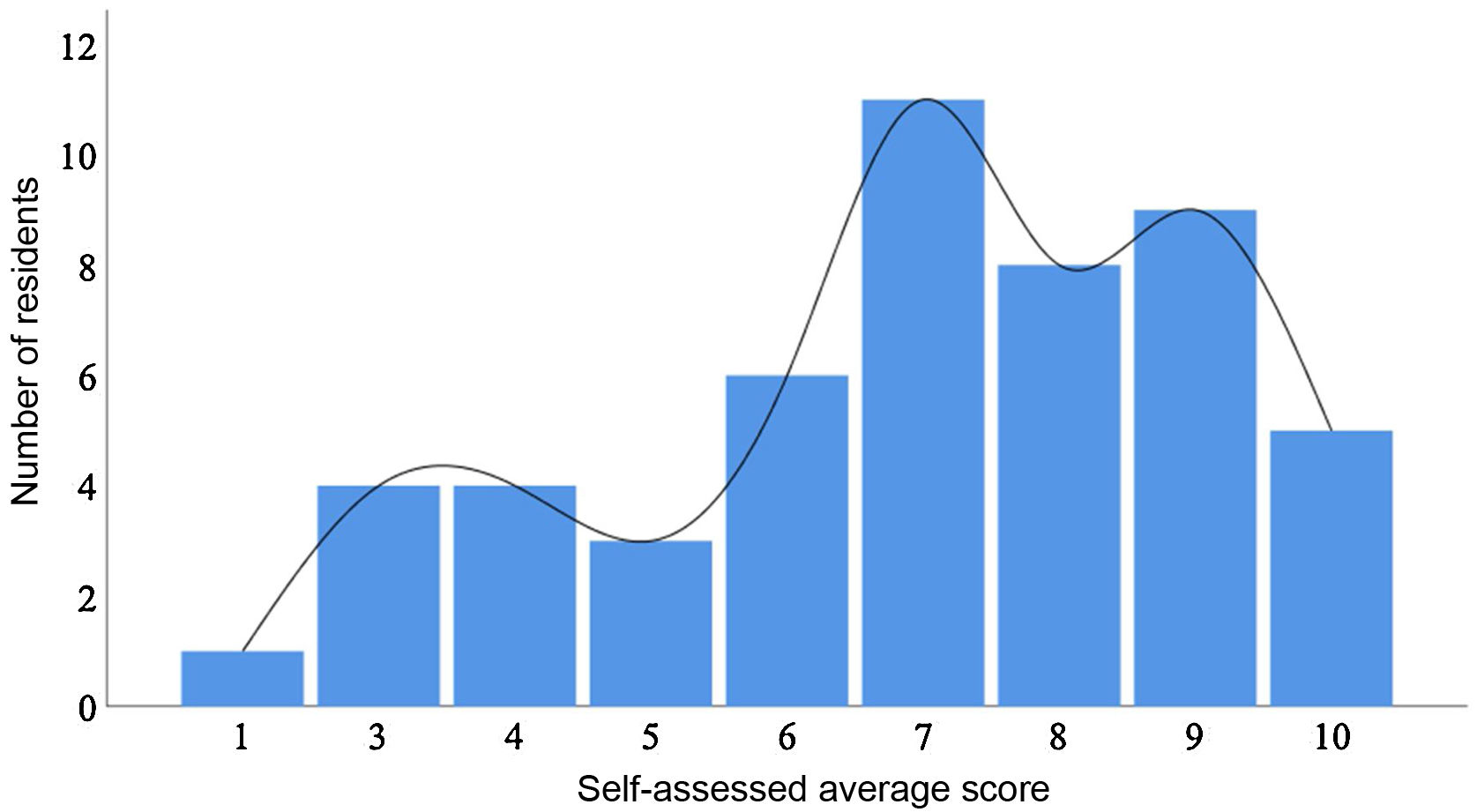

Fig. 3 shows the distribution of the self-assessed average score of the deterioration in training as a result of the pandemic (question 11).

Question 12. Has the pandemic affected your educational pathway and rotations?In total, 11.8% (6) felt their pathway was not affected, compared with 88.2% who had their rotations cancelled. Of the latter, 62.7% (32) have not been able to reschedule them compared to 25.5% (13) who have.

Question 13. Regarding the working day (37.5h per week) as a result of COVID-19 activitySome 25.5% (13) did not extend their working hours compared to 74.5% (38) who did. Of these, 40% (15) did not receive overtime pay compared to 60% (23) who did.

Question 14. Has this crisis had a negative impact on your emotional status (irritability, insomnia, anxiety, sadness, etc.)? (0 “little impact”, 10 “high impact”)The average score of the impact caused was 7.3 out of 10. One resident scored this 3; three scored it 4; seven scored it 5; six scored it six; seven scored it 7; 12 scored it 8; seven scored it 9; and eight scored it 10.

Question 15. Do you think your training time should be extended to make up for what you lost during these months?In total, 49.1% (25) would like to have their training time extended. Of these, nine (17.6%) think that what they have missed learning during COVID-19 is essential for their future compared to 16 (31.4%) who believe they are sufficiently trained. The other 50.9% advocate for not extending the training period, with 11 respondents (21.6%) believing they are well-trained and 15 (28.8%) believing they will be less well-trained than in previous years.

Question 16. Regarding research…The majority, at 68.6% (35), do research outside of their working hours, compared to six (11.8%) for whom it is included in their daily work. Overall, 9.8% (5) think it is important but have not found the time and 9.8% (5) have no interest.

Question 17. Would you like to have continued at the centre where you were trained?Some 80.4% (41) would like to have continued at the hospital where they did their residency compared to 19.6% (10) who preferred to change.

Question 18. What has happened?Overall, 45.1% (23) continued at the centre where they were trained compared to 50.1% (26) who changed hospitals and two (3.9%) who do not have a contract.

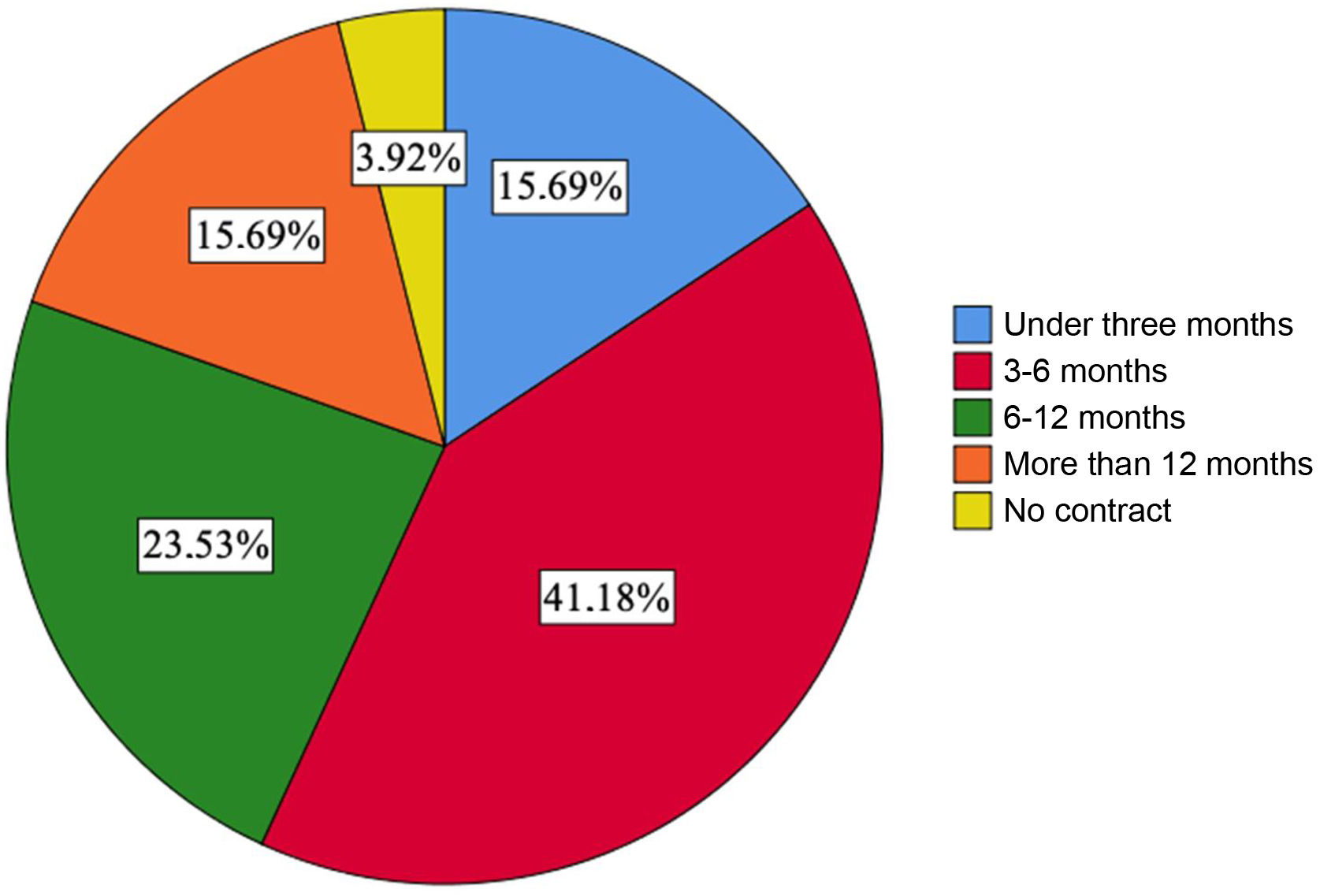

Fig. 4 shows the average duration in months of the contracts signed after completing the residency period (question 19).

Question 20. What is the preferred activity of the contract?In 49% of respondents (25), it is exclusively endocrinology, in 45.1% (23) mixed E&N and 5.9% (3) exclusively nutrition.

No differences were found in the knowledge acquired in any of the areas, comparing the centres with the lowest volume of beds (200–800) to those with more than 800 beds (p>0.05).

DiscussionThis anonymous survey has enabled us to find out directly about three fundamental aspects of the E&N specialty: firstly, an analysis of the perception of the quality of training received during the four years of the residency; secondly, future job prospects; and, finally, the consequences arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. The objective is to send these results to E&N organisations and societies, to promote the strengths and to improve the shortcomings. It may also serve to provide information to future new residents who are considering specialising in this area.

The 51 completed surveys obtained from the 77 E&N final-year residents, who are currently first-year specialists, represent a participation of 66.2%. The previous surveys were published in 2006 and 2011, with a response rate of 63% and 60%, respectively.3,4 This participation may be the result of the awareness of the group regarding the questions posed.

The residents rated their level of knowledge in these areas as satisfactory overall. No objective scale has been used with regard to the training programme for the specialty. Not all areas of theoretical knowledge have been evaluated since the main objective was to assess the most representative sections and avoid the fatigue that could be caused by completing a broader questionnaire. The highest score in the areas of diabetes, thyroid and nutrition is possibly due to the high prevalence of this disease in daily practice.11 There may also be an interest in promoting training in areas where there is a wide variety of treatments available that are continuously updated and renewed. On the other hand, adrenal and pituitary disorders may be rated less highly given the lower incidence in daily practice, added to the fact that many residents had their scheduled rotations cancelled, reinforcing these training deficits. This high overall average score, which is of note, could possibly be explained by the uniformity achieved thanks to Order SCO/3122/2006.1 With this, the National Commission for the Specialty of E&N, together with verification by the Consejo Nacional de Especialidades Médicas [Spanish National Council of Medical Specialties], published the training programme for the specialty. Added to this was the document prepared by the SEEN (Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición [Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition]) Nutrition group.12 This helped to lay the foundations of the knowledge that must be acquired during the residency and to unify the teaching plans of the different centres by specifying the portfolio of services offered by the specialty.13 With this same aim of homogenisation, courses are carried out annually across the country by the different societies.

The current trend of personalised medicine leads to sub-specialisation, with experts in increasingly defined fields.14 The objective of the residency is transversality, in order to offer training in all the areas in which the MIR could be involved as a specialist in the future. The main purpose is to train medical specialists in the skills, techniques and knowledge they will need for proper professional practice. To achieve this, it is essential to promote external rotations in reference centres, provide training mechanisms and promote scientific production.15 This contrasts with a majority of residents who have had their external rotation programme cut short, thus being at a training disadvantage compared to other years. The residents’ responses reveal that the internships are in very specific medical conditions, without specifying whether they were mandatory within the educational plan. This is probably because, due to their lower prevalence, they need to go to specific reference centres to acquire training and cover those academic shortfalls. Regarding this argument of insufficiency due to the pandemic, half of the sample considers that their residency period should be extended. The data are similar to the survey carried out by the Sociedad Española de Neurología [Spanish Society of Neurology] among its residents.16

The health crisis generated by COVID-1917 affected the MIR educational calendar. Most of the residents (96.1%) performed COVID-19-related activities for a variable period, although Zugasti et al. found that it was for at least one month in 76.2% of respondents.18 The pandemic has posed a challenge for society in general that extends beyond financial losses.19 It has also had a great emotional impact, a factor that is more difficult to measure objectively.20,21 This is a consequence of the high risk of infection, social isolation, in addition to the lack of personal contact and countertransference deriving from clinical practice. The survey reveals that this situation is causing mental health problems of varying degrees (stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, insomnia, fear, etc.) in the majority of MIRs. The detriment suffered in regards to the acquisition of knowledge was scored as 6.9 out of 10. Along these lines, a study carried out on E&N residents on the impact of the pandemic on this group has recently been published,22 as well as in other specialties such as Neurology,16 Oncology23 and, at a European level, the data from the meeting of the European Junior Doctors.18 There are probably factors that are difficult to assess but that have had a positive impact, such as the use of new technologies through telemedicine, teamwork, health education, organisation and management skills against the backdrop of a health crisis.

The model proposed in 2003 by Rizza et al.24 to determine workforce needs for endocrinologists for the years 1999–2020, seems to have been fulfilled. Their analysis demonstrated how the number of specialists that were being recruited into the workforce would not be enough to meet demand. These data were later updated by Vigersky et al.25 in 2014, confirming a shortage of professionals by 2025 due to the increase in prevalence and demand generated by diabetes mellitus, among others. Their proposal was to close this gap in five and 10 years by increasing the number of resident positions by 14.4% and 5.5% per year, respectively. In terms of demand, there is an ageing population trend that conditions the maintenance of chronic diseases, the type 2 diabetes epidemic, new technologies for diagnosis and treatment in addition to the expectation of society that healthcare is easily accessible. The survey on the situation of the medical profession in Spain (ESPM) in the 6th wave of 201926 found that unemployment is in the upper tercile compared to the rest, with 1.9% of professionals unemployed. Data on the situation of the E&N specialty in Spain from the 2007 survey6 show that the shortage of endocrinologists has diminished. The ratio of personnel per 100,000 inhabitants was 2.38 in 2006 compared to 1.47 in 1990. This is under the three recommended by the SEEN, two dedicated to endocrinology and one to nutrition,27 although in 2018 it was estimated to be 2.59, with a relatively low percentage of variability between autonomous communities of 21.53%.28 The report prepared in 2018 by Pérez et al.28 provides very relevant data, such as that in Spain there are 1,149 E&N specialists, 41.4% of whom are over 50 years of age, with a situation that is close to equilibrium. The estimated growth with a 15-year outlook is equilibrium/growing. The planning model foresees a slight surplus for 2030, with a projection of supply for that year of 2018 specialists, equivalent to 4.1/100,000 inhabitants.

The future of healthcare points to modernisation in aspects relating to a mixed care model. In other words, with a commitment to transformation and investment in technology that promotes teleworking in some sectors.29 This development and evolution of the specialty goes hand in hand with scientific, technological and pharmacological discoveries. This has led to a change in how the diagnosis and treatment of different conditions are approached.30 It is therefore essential to invest in research, something that seems to be of interest to many MIRs, although they do it during their free time.

It is striking that most of the residents (80.4%) wanted to continue in the centre where they were trained. This data reveals satisfaction with the training and the system in which it has taken place, as well as factors outside the workplace that have not been studied in this case. This is in contrast to the low rate of respondents who continued working at the centre where they were trained (45.1%). Job prospects are precarious in terms of contract duration, with 56.9% of the total being under six months. Regarding the daily exercise of the profession, the majority of contracts are in Endocrinology (49%), almost tied with the mixed model of Endocrinology and Nutrition (45.1%), with a minority (5.9%) exclusively in Nutrition. This result is a reflection of usual practice, inasmuch as the current healthcare burden of the pathology most closely linked to Nutrition is constantly growing. Professionals with the ability to be interchangeable and practice both sides of the specialty are increasingly in demand. The increased value of nutrition as a result of growing demand, awareness and its increased incidence is reflected in scientific search engines. This is so in PubMed, where an upward trending curve can be seen over the last few decades of articles published with the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) term “nutrition”, among others.

ConclusionsThe SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has led to a significant change in the training programmes of E&N MIRs throughout Spain. This has caused overexertion at work, modification of rotations with a deterioration in training, massive mobilisation towards COVID-19-related work and a negative effect on mood. The perception about the acquisition of knowledge on the most prevalent diseases of the specialty is notable. Most of the MIRs wanted to continue working at the centre where they were trained, with 45.1% continuing in their training hospital, with a contract duration of under six months and 49% exclusively practising Endocrinology.

FundingThis research did not receive any funding for its conduct.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest in relation to this study.

The authors would like to thank all the Endocrinology and Nutrition residents who participated by completing the survey.