Testosterone replacement therapy has been used for male hypogonadism since 1930. In recent decades, gel preparations of this hormone have been preferred by many patients, since in most cases a daily application suffices to obtain stable physiological concentrations. It is important to warn about the side effects that result when the drug is transmitted to someone other than the patient for whom it has been prescribed. In this regard, it is advisable for the user to cover the application zone with clothing or to wash it before coming into contact with other people.1

We report two cases of children seen for the early development of sexual characteristics to different degrees, whose fathers had been receiving treatment with testosterone gel.

The first case was a two-year-old boy referred due to penile growth with frequent erections, pubarche, and exaggerated growth in stature in the previous few months. A physical examination revealed tallness for the age of the patient and the height of the parents, a muscled body, pubarche, enlarged penis (Tanner class III), and a rough and pigmented scrotum, but no change in testis volume. Laboratory tests showed a very high total testosterone level for his age, with suppressed LH and FSH, and no response of these hormones to leuprolide stimulation. The bone age was advanced by three years. His testosterone level normalized after gel exposure was discontinued, with a regression of the phenotypical changes. The boy had a normal growth rate and prepubertal testicular volume over the subsequent four years.

The second case was a 6-year-old boy seen due to the appearance of pubic hair and penile growth over the previous three months. The examination also revealed tallness and a testicle volume of 3mL. Laboratory tests showed isolated total testosterone elevation with suppressed gonadotropins and no response to leuprolide. The bone age was advanced by 1.5 years. Three months after the suppression of exposure to the gel, the testicle volume had increased to 4mL, indicating the start of puberty, with a high growth rate. The testosterone concentrations remained high, and an increase in gonadotropin levels was also noted, indicative of central activation. Hypothalamic-pituitary magnetic resonance imaging showed no abnormal findings, and treatment was started with monthly triptorelin.

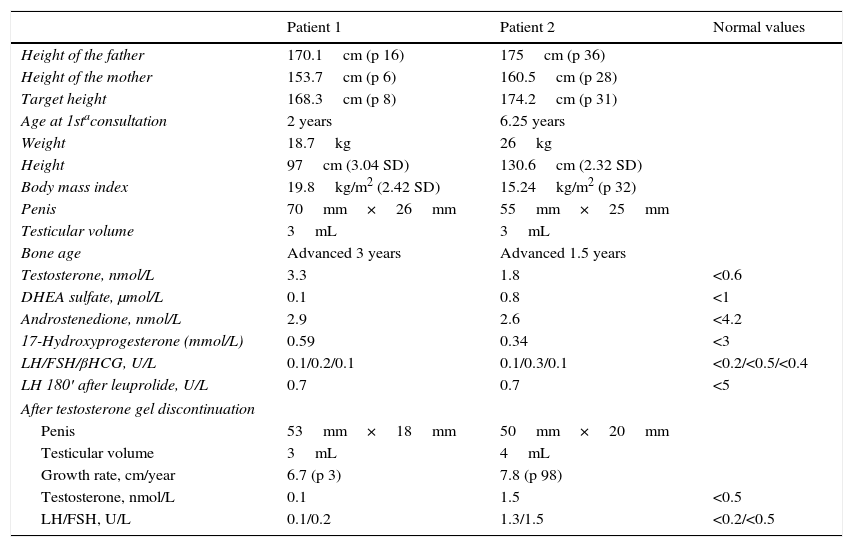

In both cases, the fathers had undergone orchiectomy due to seminoma and were receiving replacement therapy with testosterone gel. The fathers were aware of the risk of transferring the gel to their partners, and followed the recommendations for avoiding exposure. However, they did not apply such measures in the case of their children, and played and hugged them while naked from the waist up after applying the gel to the abdomen or chest (both patients were seen during the summer months). Table 1 shows the clinical and laboratory data for the two patients.

Patient clinical and laboratory test data.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Normal values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height of the father | 170.1cm (p 16) | 175cm (p 36) | |

| Height of the mother | 153.7cm (p 6) | 160.5cm (p 28) | |

| Target height | 168.3cm (p 8) | 174.2cm (p 31) | |

| Age at 1staconsultation | 2 years | 6.25 years | |

| Weight | 18.7kg | 26kg | |

| Height | 97cm (3.04 SD) | 130.6cm (2.32 SD) | |

| Body mass index | 19.8kg/m2 (2.42 SD) | 15.24kg/m2 (p 32) | |

| Penis | 70mm×26mm | 55mm×25mm | |

| Testicular volume | 3mL | 3mL | |

| Bone age | Advanced 3 years | Advanced 1.5 years | |

| Testosterone, nmol/L | 3.3 | 1.8 | <0.6 |

| DHEA sulfate, μmol/L | 0.1 | 0.8 | <1 |

| Androstenedione, nmol/L | 2.9 | 2.6 | <4.2 |

| 17-Hydroxyprogesterone (mmol/L) | 0.59 | 0.34 | <3 |

| LH/FSH/βHCG, U/L | 0.1/0.2/0.1 | 0.1/0.3/0.1 | <0.2/<0.5/<0.4 |

| LH 180′ after leuprolide, U/L | 0.7 | 0.7 | <5 |

| After testosterone gel discontinuation | |||

| Penis | 53mm×18mm | 50mm×20mm | |

| Testicular volume | 3mL | 4mL | |

| Growth rate, cm/year | 6.7 (p 3) | 7.8 (p 98) | |

| Testosterone, nmol/L | 0.1 | 1.5 | <0.5 |

| LH/FSH, U/L | 0.1/0.2 | 1.3/1.5 | <0.2/<0.5 |

βHCG: beta-human chorionic gonadotropin; SD: standard deviation; DHEA: dehydroepiandrosterone; FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone; LH: luteinizing hormone; p: percentile.

The immediate consequence of testosterone gel transmission from father to prepubertal offspring is hyperandrogenism, which produces precocious virilization (an increase in size of the penis or clitoris, with no associated increase in testicle size in males, early pubarche, accelerated growth and advanced bone age). A number of such cases have been documented in the literature.2–5 There has even been a report of prenatal virilization in a female fetus.6 Hyperandrogenism was transient in all those cases, with a normalization of testosterone levels once exposure was ended.

Another less common consequence is the triggering of central early puberty due to exposure to testosterone, a situation which is not reversible. It is known that children with high exogenous or endogenous sex steroid levels, such as those induced by a tumor, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, McCune-Albright syndrome, or testotoxicosis, may develop central early puberty by two possible mechanisms: hypothalamic priming by the high steroid levels if not adequately treated7 or after a sudden decrease in such levels once control of the disease has been achieved, or the discontinuation of exposure in the case of an exogenous origin,8 as occurred in the second case reported. The former mechanism was implicated in the case of a 5-year-old boy who developed central precocious puberty after 5 years of exposure to testosterone, and that persisted after the ending of this exposure.9

In 2009, the United States Food and Drug Administration published a warning on the risk of testosterone transfer to children.10 Patients who use the drug should be warned about the possible consequences for their offspring and for other children in the family, and a potential history of exposure should be sought in children seen for early sexual characteristics or excess growth.

Please cite this article as: García García E, Jiménez Varo I. Posibles consecuencias en los niños del uso de gel de testosterona por sus padres. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2017;64:278–280.