Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHP) during pregnancy is an exceptional disorder with symptoms that can be confused with those of pregnancy itself.1 The physiological changes experienced by the patient complicate the diagnosis of PHP.1,2 Hypoalbuminemia, calcium transport through the placenta, high estrogen levels and the increase in glomerular filtration with the consequent rise in urinary calcium excretion inherent in pregnancy all result in apparently low blood calcium concentrations, thereby contributing to the masking of PHP.2

Maternal complications have been described in up to 67% of the patients3,4 (hyperemesis, nephrolithiasis, muscle weakness and psychological symptoms, among others)5 and in 80% of the fetuses (hypoparathyroidism, hypocalcemic tetany, mental retardation and low birth weight).5 The untreated disease can alter fetal development2 and increase fetal mortality.5

The diagnosis is based on the laboratory test findings (elevated serum calcium and PTH levels), and a differential diagnosis should be made with familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia.6 Neck ultrasound exploration and parathyroid scintigraphy with 99mTc-sestamibi are useful for the localization of PHP, though the latter technique is contraindicated during pregnancy, due to the risk of fetal irradiation.4

The medical treatment options include hydration and the administration of calcitonin for short-term control; bisphosphonates in the case of medical emergencies (since they cross the placental barrier); and calcimimetic agents such as cinacalcet, which offer long-term hypercalcemia control, though little experience is available concerning their use during pregnancy.7 Adequate treatment can result in a four-fold decrease in the incidence of complications.3

We present the case of a 36-year-old woman, an ex-smoker with no relevant diseases, who had been subjected to septoplasty in childhood. Her family history comprised esophageal and gastric cancer at age 64 years in the father, hyperthyroidism in three paternal aunts, and lung cancer and parathyroid adenoma subjected to surgery in her maternal great aunt.

With regard to the obstetric history, the patient had two previous pregnancies with two eutocic deliveries to term in 2012 and 2013 (two females with good birth weight). Hyperemesis gravidarum was recorded during both pregnancies. During follow-up of her second pregnancy, the patient presented an altered O'Sullivan test, with a subsequent negative long oral glucose tolerance test result.

At the time, she was being monitored for a new pregnancy in a private clinic, with normal laboratory test results in the first trimester and low risk aneuploidy screening findings. In August 2016, in the seventh week of pregnancy, the patient started to suffer nausea and vomiting, and lost 5kg in weight. The laboratory test findings were within normal limits, and metoclopramide was prescribed. In week 17 of pregnancy, total serum calcium was found to be 12.9mg/dl (normal range: 8.6–10.2mg/dl); PTH was determined and found to be 264pg/ml (normal range: 12–65pg/ml). Primary hyperparathyroidism was diagnosed, and the patient was admitted to the same center for two days for hydration purposes. Total serum calcium at discharge was 11.3mg/dl, and no serum albumin or calciuria measurements were made. Neck ultrasound revealed a lesion suggestive of a parathyroid adenoma posterior to the upper pole of the right thyroid lobe. Renal ultrasound in turn showed evidence of nephrocalcinosis. The patient subsequently reported to our high risk obstetrics clinic for treatment.

In our hospital the study was completed with the multidisciplinary participation of the Departments of Obstetrics, Endocrinology and ENT.

While awaiting the results of complementary tests requested by these Departments, the patient developed incoercible vomiting and a poor general condition. A physical examination revealed dehydration, and the laboratory tests showed serum calcium 13.6mg/dl (14.2mg/dl corrected with albumin) and magnesium 1.48mg/dl (normal range: 1.8–2.4mg/dl). Admission for supportive medical treatment and symptoms control was, therefore, decided upon.

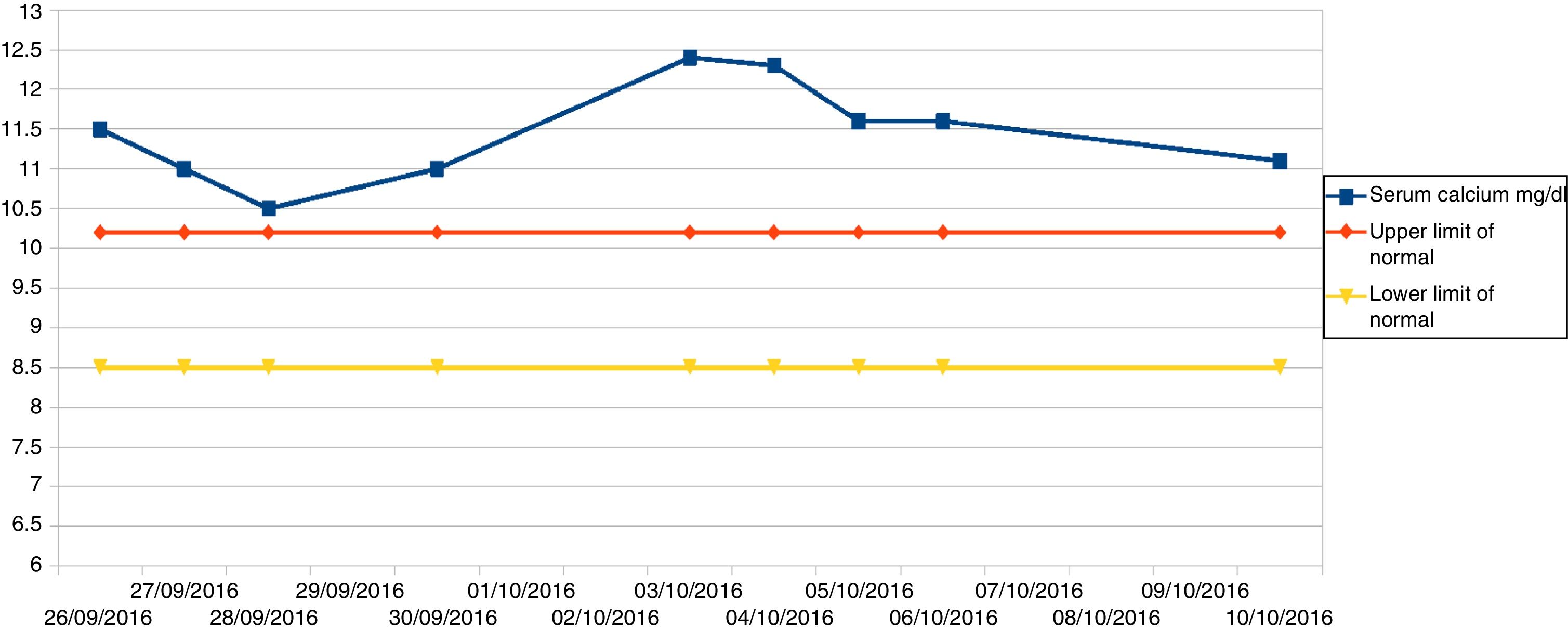

The patient remained under observation with intense fluid therapy (3l a day) and laboratory controls. Fig. 1 shows the total serum calcium levels recorded during admission.

The full laboratory tests yielded the following results: hemoglobin 8.8g/dl, calcium 11.5mg/dl (12.1mg/dl corrected with albumin), phosphorus 1.7mg/dl, IGF-1 63ng/ml, vitamin D (calcidiol) 15ng/ml, PTH 94pg/ml, and potassium, chloride, creatinine, thyroid hormones, antithyroid antibodies, daytime basal serum cortisol, GH, calcitonin, prolactin, FSH, LH, gastrin, Ca19.9 marker and serum chromogranin A within normal limits, as were 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, vanillylmandelic acid, catecholamines and metanephrines in 24h urine.

After discarding pheochromocytoma on the basis of the laboratory test findings, and in the absence of surgical contraindications, minimally invasive surgery was decided upon at 21 weeks and four days of pregnancy. A right superior parathyroidectomy was performed. The surgical piece measured 15mm in maximum diameter and weighed 773mg (normal parathyroid gland dimensions: 5mm in maximum diameter and 30mg in weight). An intraoperative PTH decrease of 69.23% was observed (156pg/ml before surgery, versus 48pg/ml as determined 15min after the removal of the adenoma); the other glands were therefore not explored. The intraoperative biopsy identified an increased parathyroid parenchyma weight consistent with adenoma/hyperplasia. The deferred study reported parathyroid gland parenchyma with histological alterations consistent with adenoma/hyperplasia of the parathyroid gland.

During the immediate postoperative period, the patient experienced transient paresthesias in both hands. Serum calcium measurements every 12h revealed no early or late hypocalcemia or other complications, and no calcium supplements proved necessary. Total serum calcium after 24h was 8.5mg/dl (9.3mg/dl corrected with albumin), with ionized calcium 1.16mmol/l (normal range: 1.15–1.29), albumin 3g/dl (normal range: 2.8–5) and phosphate 2.8 (normal range: 2.7–4.5). In view of the favorable course, the patient was discharged with scheduled controls at the high risk obstetric clinic, and at the Departments of Endocrinology and ENT.

Follow-up in the second trimester of pregnancy revealed mild nausea, while the laboratory tests showed a positive O'Sullivan test and serum calcium 8.9mg/dl (9.5mg/dl corrected with albumin). The anemia improved with iron treatment. Vomiting subsided in week 27, and the oral glucose tolerance test (100g) proved normal. In week 32 the vitamin D (calcidiol) levels (30ng/ml) were seen to have normalized after treatment with cholecalciferol. The remainder of the pregnancy progressed normally, without nausea or vomiting, and with an estimated fetal weight of 3079g in week 36.

With regard to the fetal ultrasound findings, slight triple-vessel disproportion was observed in week 20, with no other significant findings. Slight right-side cavity dominance was noted in week 24, and in week 32 an average-high suspicion of aortic coarctation was documented, with an estimated fetal weight of 1998g.

Spontaneous delivery took place following 8h of premature membrane rupture after 40 weeks and three days of pregnancy, with the birth of a male with good body weight. Neonatal echocardiography showed no aortic coarctation, though a small anterior interventricular communication was identified. The control laboratory tests showed ionic calcium 1.26mmol/dl, total calcium 9.6mg/dl, PTH 17pg/ml and vitamin D 27ng/ml, all of these values being within the normal ranges. The study was completed with an abdominal ultrasound exploration that revealed a punctate liver calcification of scant relevance.

Although PHP is the third most common endocrine disorder in the general population after diabetes mellitus and thyroid gland disease, less than 1% of all cases of PHP are diagnosed during pregnancy.4

The nausea and vomiting in our patient were probably not exclusively due to PHP but also to hyperemesis gravidarum. In fact, these symptoms did not subside until week 27 of pregnancy. We found no evidence relating the neonatal findings (liver calcification, small interventricular communication, mild aortic isthmus hypoplasia) to the maternal antecedent of PHP.

Approximately 200 articles reporting PHP in pregnancy have been published to date; of these, four cases were treated with cinacalcet7 and fewer than 40 underwent surgery. Two of these latter cases were secondary to an ectopic parathyroid adenoma located in the mediastinum,8 while one coexisted with thyroid papillary carcinoma.5 All the authors consider the diagnosis during pregnancy to be complicated; the clinical manifestations are highly variable, and the maternal-fetal complications are very important.

Surgery is the treatment of choice in the second trimester of pregnancy, and is a safe option.9–11 Such treatment has classically been based on exploration and direct visualization of all four parathyroid glands. The aim is to locate the diseased gland and check that the other glands are apparently normal, so avoiding the risk of leaving residual disease in cases of double hyperplasia or adenomas. However, improvements in preoperative localization techniques, and especially the possibility of a biochemical resolution of the disease through the intraoperative determination of PTH, have facilitated the adoption of more limited surgical approaches. This allows for a significant shortening of surgery time, and, in particular, the manipulation of healthy glands is avoided, thereby substantially reducing the appearance of postoperative hypoparathyroidism.

In conclusion, the early detection of this disorder, followed by adequate treatment, has been shown to greatly reduce maternal and fetal complications.1

Please cite this article as: Rostom A, de la Calle M, Bartha JL, Castro A, Lecumberri B. Hiperparatiroidismo primario diagnosticado y tratado quirúrgicamente durante la gestación. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2018;65:239–241.