Several sweeteners are introduced to replace sucrose in the human diet. However, they had their own limitations and concerns, particularly in terms of their taste and their long-term health consequences. This study examined the effect of a new mixture of sugars and sugar alcohol on the postprandial blood glucose levels and its possible gastrointestinal (GI) adverse reactions in human adults.

MethodsIn this double-blind three-way randomized clinical trial, adults (21 with type 2 diabetes and 20 healthy) received 300ml of three beverages containing 50g glucose, sucrose, and lacritose (a mixture of lactose, fructose, sucrose, and erythritol) when they were in the fasted state in a random order. Postprandial serum glucose was checked every 30min up to 2h and the gastrointestinal reactions were collected.

ResultsThe mean serum glucose was significantly lower in all time points after ingestion of the lacritose for participants with type 2 diabetes compared to glucose and sucrose (P<0.05). The blood glucose levels were significantly lower in the 30th and 60th min for healthy subjects (P<0.05). Adverse GI reactions were not significant between the test beverages.

ConclusionsThe ingestion of a 50g dose of lacritose containing lactose, fructose, sucrose, and erythritol, led to an improved blood glucose levels without any significant adverse effect compared to the same amount of glucose and sucrose. Studying the long-term effects of lacritose on appetite, metabolic markers and adverse reactions is recommended. The trial was registered in Iranian registry of clinical trials: IRCT2015050912571N2.

Se han utilizado varios edulcorantes para sustituir a la sacarosa en la dieta humana. Sin embargo, tenían sus propias limitaciones y problemas, sobre todo por su sabor y sus consecuencias a largo plazo para la salud. En este estudio se explora el efecto de una nueva muestra de azúcares y alcohol de azúcar en los niveles de glucemia posprandial y las posibles reacciones adversas digestivas a ella en adultos humanos.

MétodosEn este ensayo clínico doble ciego aleatorizado de tres vías, adultos (21 con diabetes tipo 2 y 20 sanos) recibieron 300ml de tres bebidas que contenían 50g de glucosa, sacarosa y lacritosa (una mezcla de lactosa, fructosa, sacarosa y eritritol) en orden aleatorio en ayunas. Se comprobó la glucose sérica posprandial cada 30 minutos hasta las dos horas y se recogieron las reacciones digestivas.

ResultadosLos valores medios de glucosa en suero eran significativamente menores en todos los puntos temporales tras la ingesta de lacritosa que tras la de glucosa y sacarosa en los participantes con diabetes tipo 2 (P<0,05). Los niveles de glucemia eran significativamente menores a los 30 y 60 minutos en los sujetos sanos (P<0,05). No había diferencias significativas en las reacciones digestivas adversas entre las bebidas estudiadas.

ConclusionesLa ingesta de una dosis de 50g de lacritosa que contiene lactosa, fructosa, sacarosa y eritritol, mejoró los niveles de glucemia sin efectos adversos importantes comparada con la misma cantidad de glucosa y sacarosa. Se recomienda estudiar los efectos a largo plazo de la lacritosa en el apetito, los marcadores metabólicos y las reacciones adversas. El ensayo se inscribió en el registro de ensayos clínicos de Irán: IRCT2015050912571N2.

Throughout history, inherent human's tendency to sweet taste make him effort to find a new source of sweeteners according to circumstances.1 In different people, this tendency is influenced by some factors such as genetics,2 exposure to sweets in childhood,3 satiety or hunger 4and mental status as stress.5 Finding different sweeteners other than sucrose is particularly important for patients with diabetes because these patients have low glucose tolerance and their blood glucose increases dramatically after ingesting sucrose.6 Diabetes is now one of the main problems in the health of human society and the most frequent cause of blindness, non-traumatic amputation and also the second most common cause of kidney failure.7 Therefore, patients with diabetes are recommended not to consume added sugar.8

Various compounds such as sugars, sugar alcohols and non-sugar compounds, for instance, stevia, xylitol, and aspartame have been introduced to induce the sweet taste in food industry.9,10 Substitutes of sucrose are the main component of low-calorie products.11 Consumers prefer these products for reducing calorie intake, controlling body weight and help to maintain healthy life.12 Although the majority of sweeteners are also low calorie, they do not have the same taste as sucrose 13and they do not affect the appetite or the quantity of food consumed by individuals.14

According to the above, a new sweetener was introduced by mixing four sugars (lactose, fructose, sucrose, and erythritol) under the name of lacritose. This mixture of sugars compared to other conventional sweeteners contains sucrose,15 fructose16 and lactose which might have effects on reducing appetite. On the other hand, it has lower energy compared the pure sucrose. Furthermore, as it is not completely from sucrose, and contains erythritol, it might not dramatically increase the blood glucose concentrations which might be helpful for diabetic patients.17Erythritol is a member of sugar alcohols family also known as polyols 18with glycemic index equal to zero and 0.2 kcal per gram.19 These compounds exist in fruit and vegetables like mushrooms and grapes.20 Sugar alcohols are valuable because of their sweetness, low caloric content besides being non-carcinogen.21 Although previous studies have shown sugars can interact each other during absorption in the intestine and slow down or increase each other's absorption 22and lacritose is a mixture of four sweeteners currently used in food industry including lactose, fructose, sucrose and erythritol, glycemic response and also possible gastrointestinal adverse reactions to this sweetener are not clear yet. Therefore, the present study plans to examine the effect of one 50 gram dose of this sweetener on blood glucose levels and the possible gastrointestinal reactions compared with sugar and glucose in healthy adults and also patients with diabetes.

Patients and methodsThe study design and protocol was approved by Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences’ ethics committee (ethics certificate number: IR.SSU.SPH.REC.1394.31) and registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT: http://www.irct.ir), under registration code of IRCT2015050912571N2. All participants filled an informed consent at the start of the study. The study is also reported based on CONSORT statement.23 We modified the study flow diagram because the current investigation was a randomized three-way cross-over clinical trial.

SubjectsStudy participants were invited via advertisement from Baqaipoor obesity clinic, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. We recruited two groups of participants. Adults with type 2 diabetes (n=21) and healthy subjects (n=20). Inclusion criteria for patients with diabetes mellitus were as follows: (1) aged 20–60, (2) had fasting blood glucose (FBG) lower than 200mg/dl, (3) used hypoglycemic oral medications, (4) did not change their medication for dyslipidemia, hypertension or blood glucose control within the last month prior to the study and (5) did not use insulin. Healthy subjects were included in the study if they (1) aged 20–60, (2) free of any metabolic or chronic diseases based on their self-report (3) and their FBG was lower than 100mg/dl.

Participants were withdrawn if: (1) became pregnant, developed severe infection, endocrine disorders, and any other acute problems, (2) had willing to be excluded from the study and (3) did not attend more than two study periods. We did not assess the glucose lowering medications taken by the patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the present study. In fact, the glucose lowering medications because, we asked the participants not to change their medications during the study period. Furthermore, as this study was a crossover trial the participants were controlled by themselves. In addition, the duration of the study was low and the drugs did not change during the study.

Study designThe present study was a double-blind three way randomized cross-over clinical trial in which each participant served as his/her control. Participants were randomly assigned into six rolling methods (ABC, ACB, BAC, BCA, CAB, and CBA) to drink the three test beverages (lacritose, glucose and sucrose) by a person not aware of the study objectives. In order to blind the study personnel and participants, the three sugars which were the same in the appearance, smell and taste were packed in the similar containers which were marked as A, B and C once by a person not aware of the study protocol and its outcomes. The rolling method for each participant was written on a paper and concealed in an opaque envelope before the start of the study. The pockets were opened at the start of the study at the entrance of participants to the laboratory. Each participant received only one 50g dose of lacritose, sucrose and glucose beverage solved in 300ml of tap water. The intervention beverages were drank by the study participants on the same days of the week (6 days apart).

Intervention detailsOn each intervention day, participants were asked to be presented in the research laboratory when they were fasted overnight for at least 10h. After filling demographic questionnaire, anthropometric assessments were done. Then the rolling method pocket was opened for the study attendee. After that, a blood sample was taken when the participant was in the fasted state. After sampling the blood, the test beverage was drank by participant and after that blood samples were taken each 30min up to 2h. Participants were not allowed to consume any meals, tea, coffee, drugs and to smoke or to do intense physical activity until the last blood glucose test was taken. A gastrointestinal reaction questionnaire was filled for each participant one day after the intervention day by a trained nutritionist on the phone.

The characteristics and safety of lacritoseThe organoleptic, microbiological and chemical tests for lacritose were done by the laboratory of Food and Drug Department in Yazd province and also its lower calorie content and its similar taste compared to sucrose was approved. Each 100g of lacritose was consisted of 27.4g of lactose, 12.9g of fructose, 5.57g of sucrose, and 54.13g of erythritol. Its glycemic index was 19.72 and it had about 1.98 kcal/g energy. The maximum tolerated dose for erythritol which is a sugar alcohol is about 0.71 g/kg body weight and this amount is about 0.72 g/kg body weight for lactose.1,24 Therefore, a reference man with about 70 kg body weight25 can consume 91.8 g lacritose per day. As the present study was an exploratory one, we used just one 50g dose of the sweetener for each participant. Based on the tolerable doses for lactose and erythritol, this 50 g dose can be tolerated by an individual with 19.2kg body weight. Therefore, the each ingredient was lower than the maximum tolerated doses. The control sugars were glucose and sucrose.

Anthropometric measurementsA trained practitioner assessed anthropometric measurements at baseline. Height was measured with the accuracy of 0.5cm using stadiometer attached to the wall, and weight was measured with the accuracy of 100 grams using a digital scale (Seca, model no.: 803, Homburg, Germany) with minimum possible clothing. All the measurements were done three times and the mean was recorded then BMI was calculated [weight (kg) divided by the height square (m2)].

Blood glucose measurementCapillary blood samples were used to identify blood glucose levels in healthy subjects (Arkray, model: Glucocard 01, Japan). Participants’ venous blood samples were taken at fasted state (T0), then every 0.5h (T1, T2 and T3) till 2h after the ingestion of test beverages (T4) and analyzed by glucose oxidase method using an automatic analyzer (BioSystem model: BA 400, Barcelona, Spain).

Adverse reactions assessmentThe participants were contacted the day after each intervention day to assess possible gastrointestinal adverse effects including pain in the stomach and abdomen, heart burn, reflux, appetite, etc. using a gastrointestinal symptoms questionnaire which was validated previously for this purpose.26

Statistical analysisRandomization and statistical analysis were done using IBM SPSS software version 20 (IBM SPSS, Tokyo, Japan). Descriptive statistics are shown as means ± standard deviations (SDs) or standard error of means (SEs) where indicated. Normal distribution of outcome variables was assessed by using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Differences in blood glucose level between tests beverages were analyzed using generalized linear model (GLM) repeated measures adjusted for age, gender, BMI and rolling method as between person covariates. The proportion of gastrointestinal symptoms one day after ingestion of the test beverages was compared using Cochran's Q test. P values less than 0.05 (two tailed) were considered as statistically significant.

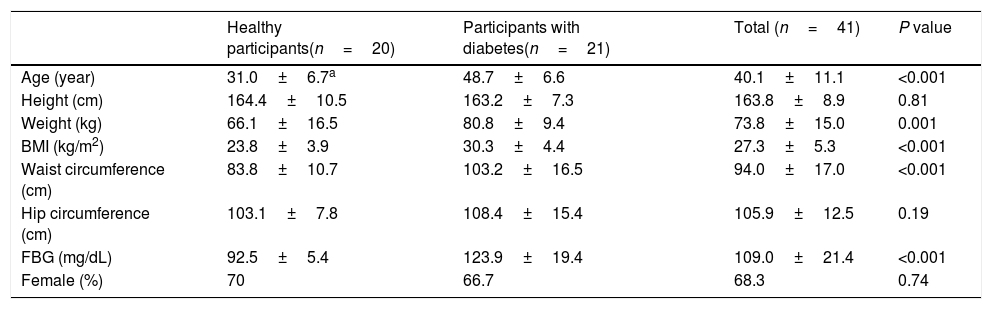

ResultsIn total, out of 41 participants assessed for eligibility to be included in the present study 40 participants, including 20 diabetic patients and 20 healthy individuals, aged 40.10 ± 11.09 (mean ± SD) years were enrolled and successfully completed the study. The recruitment started from February 2016 to October 2016. The study flow diagram for patients with type 2 diabetes and healthy subjects are presented in Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2, respectively. Baseline characteristics of the study attendants are presented in Table 1.

General characteristics of study participants.

| Healthy participants(n=20) | Participants with diabetes(n=21) | Total (n=41) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 31.0±6.7a | 48.7±6.6 | 40.1±11.1 | <0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 164.4±10.5 | 163.2±7.3 | 163.8±8.9 | 0.81 |

| Weight (kg) | 66.1±16.5 | 80.8±9.4 | 73.8±15.0 | 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.8±3.9 | 30.3±4.4 | 27.3±5.3 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 83.8±10.7 | 103.2±16.5 | 94.0±17.0 | <0.001 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 103.1±7.8 | 108.4±15.4 | 105.9±12.5 | 0.19 |

| FBG (mg/dL) | 92.5±5.4 | 123.9±19.4 | 109.0±21.4 | <0.001 |

| Female (%) | 70 | 66.7 | 68.3 | 0.74 |

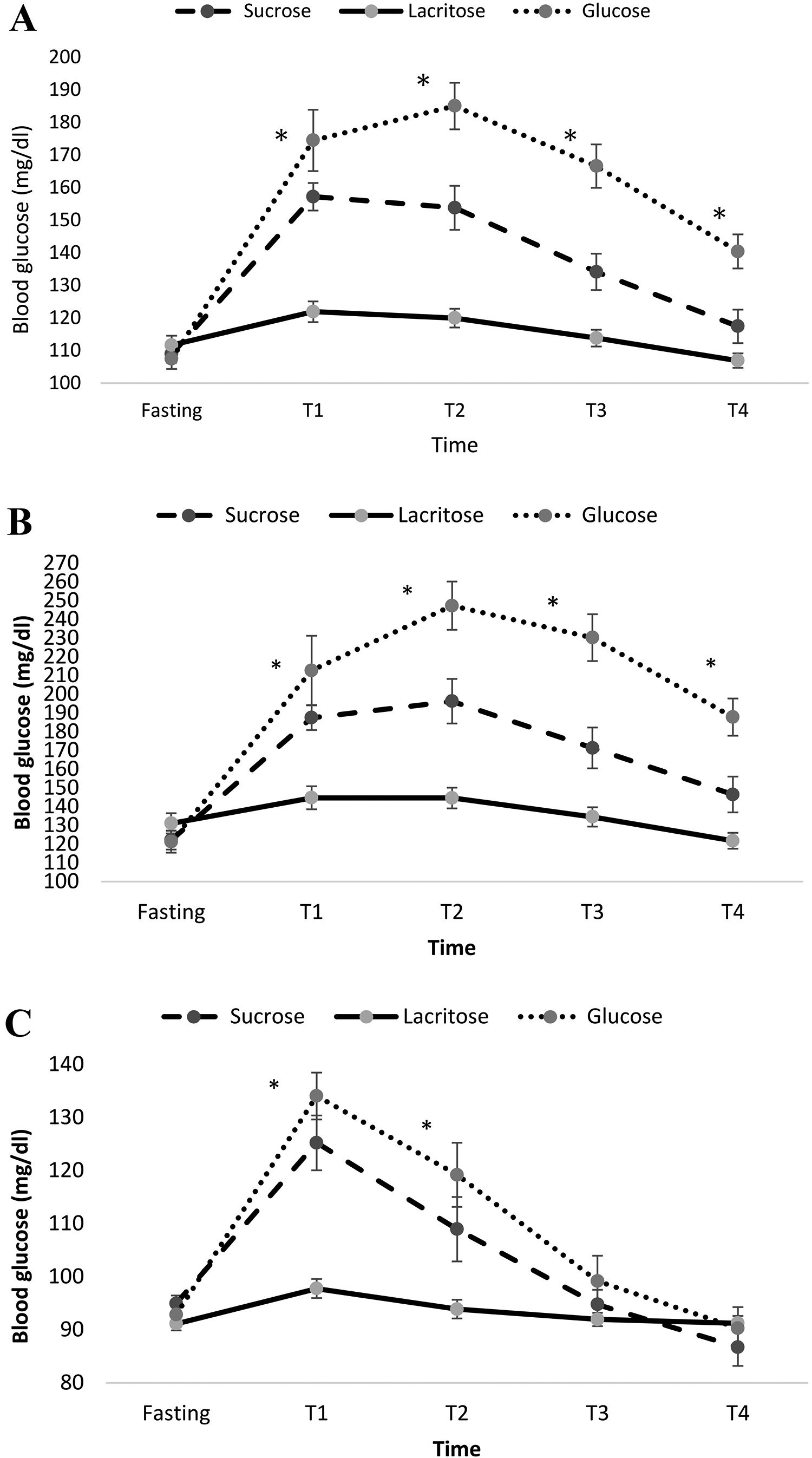

Fig. 1A represents the effects of the three test beverages on blood glucose in fasting, T1 (half hour), T2 (one hour) T3 (one and half hour) and T4 (two hour) for the total population. The mean blood glucose levels were compared after adjusting for BMI, gender, age and rolling method. Mean blood glucose was significantly lower during consumptions of lacritose compared to sucrose and glucose (mean ± standard error (SE) for lacritose: 114.9±2.5, glucose: 154.8±5.0, sucrose: 134.3±4.0, P-value ˂0.001). Also the increasing of blood glucose at different times was significantly different between the three drinks. Mean ± SE of blood glucose levels for participants with diabetes mellitus and healthy subjects, are represented in Fig. 1B and C respectively. In both groups blood glucose was significantly lower after ingesting lacritose when compared to other beverages, after adjustment for BMI, gender, age and rolling method (P-value <0.05). Blood glucose in T3 and T4 returned to baseline normal levels for healthy subjects after drinking each beverage.

Mean±standard error (SE) of blood glucose form fasting and each half hour after consumption of the test beverages in the total population (A), participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus (B) and healthy participants without diabetes (C). Results were adjusted for group, age, gender and BMI. Significant difference between the test beverages at each time point is represented using asterisk (P<0.05).

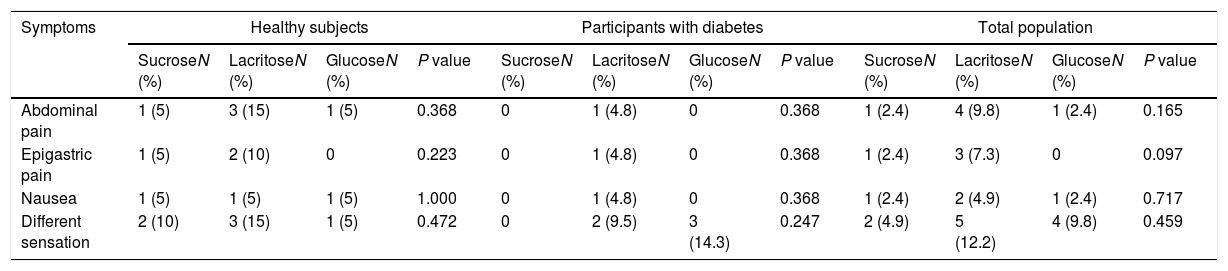

A Few participants reported abdominal pain, epigastric pain and also nausea after ingestion of the test beverages. The number of participants reporting these symptoms were higher when they ingested lacritose, however the difference between beverages were not statistically significant for abdominal pain (P-value=0.165), epigastric pain (P-value=0.097) and nausea (P-value=0.717). The feeling of a different sensation in the gastrointestinal tract was also asked and it was not significant between the test beverages (P-value >0.05). Table 2 shows the difference in adverse symptoms in total population as well as participants with diabetes and healthy subjects. None of the study participants reported postprandial or fasting abdominal pain, epigastric pain during the whole day or when asleep, heartburn, regurgitation, abdominal rumbling, bloating, feeling empty, vomiting, loss of appetite, postprandial fullness, belching, flatulence, hematemesis, dysphagia, and unusual symptoms in stool; therefore, the data are not provided in Table 2.

Gastrointestinal reaction based on test beverages in healthy and diabetics patients as well as total population.

| Symptoms | Healthy subjects | Participants with diabetes | Total population | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SucroseN (%) | LacritoseN (%) | GlucoseN (%) | P value | SucroseN (%) | LacritoseN (%) | GlucoseN (%) | P value | SucroseN (%) | LacritoseN (%) | GlucoseN (%) | P value | |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (5) | 3 (15) | 1 (5) | 0.368 | 0 | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 0.368 | 1 (2.4) | 4 (9.8) | 1 (2.4) | 0.165 |

| Epigastric pain | 1 (5) | 2 (10) | 0 | 0.223 | 0 | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 0.368 | 1 (2.4) | 3 (7.3) | 0 | 0.097 |

| Nausea | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 1.000 | 0 | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 0.368 | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.4) | 0.717 |

| Different sensation | 2 (10) | 3 (15) | 1 (5) | 0.472 | 0 | 2 (9.5) | 3 (14.3) | 0.247 | 2 (4.9) | 5 (12.2) | 4 (9.8) | 0.459 |

To our knowledge, this is the first study on the effect of a blend of natural sugars (lactose, fructose, sucrose, erythritol), on blood glucose and its possible adverse reaction. Our results show that the consumption of lacritose significantly improves blood glucose control when compared to the same amount of glucose and sucrose while this mixture tastes like sucrose and its energy content is nearly half of the sucrose. On the other hand, although lacritose contains lactose, the gastrointestinal adverse reactions after its ingestion was not significantly different compared to glucose and sucrose.

It is supposed that the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is an important metabolic substance which is believed to stimulate insulin secretion and help to normalize blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes.27 A Study showed that, GLP-1 secretion increases after ingestion of glucose and fructose but not aspartame, acesulfame K28 or sucralose.28,29 In another hand, replacement of sucrose with erythritol in meals caused lower blood glucose after ingestion but not 2h after ingestion and the GLP-1 levels were similar.30

In a study done by Gregersen et al.,31 on another natural sweetener, stevia, it was shown that stevia can control the postprandial blood glucose. Shin et al.,32 also showed erythritol consumption does not significantly affect the fasting blood glucose in pre-diabetic patients. Fructose also did not show a high insulin response.33 Erythritol is revealed to lower the insulin response in comparison with sucrose.30 This is while a study done by Tey et al.34 showed that sweetened beverages by aspartame, monk fruit, stevia in comparison with sucrose, not only did not reduce blood glucose but also led to consuming more calories at an ad libitum lunch. The difference of the present sweetener to the existing ones is that it is a mixture of four common sugars. It is suggested that, erythritol might exert its anti-hypoglycemic effect, using two mechanisms. First, it reduces glucose absorption in the first quarter of small intestine, and then, in patients with diabetes, erythritol reduces the induction of raising glucose 6 phosphatase activity in liver.17

In a recently published study, it was revealed that the calorie-free beverages containing aspartame-, monk fruit, and stevia-sweetened beverages do not significantly affect postprandial glucose, insulin and total daily energy intake when compared with sucrose.34

Lohner et al.35 reviewed publications on the health outcomes of non-nutritive sweeteners (NNS). They included studies on artificial, natural and non-caloric sweeteners. Health outcomes which were investigated were mostly about appetite, the risk of diabetes, cancer, dental cavities and also weight gain and obesity. Other outcomes such as mental and neurological effects, risk of preterm delivery, other chronic diseases such as cardiovascular and kidney diseases were also investigated. They could not reveal any conclusive evidence regarding the beneficial or harmful effect of NNS on the mentioned outcomes. Lacritose is a mixture of four sugar which are available in the daily diet, concerns for its effect on risk of diseases seem to be lower.

There are some limitations that should be considered when interpreting our results. In this work we included a limited number of participants and also we did not investigate the effect of lacritose on appetite and long-term outcomes. As we were testing the lacritose as a mixture of sucrose, fructose, lactose, and erythritol for the first time, we used a 50g dose to test its acute effect on blood glucose levels and its possible gastrointestinal symptoms. The long-term effect of lacritose on health as well as its possible effect on microbiota are still unknown and need to be more studied in the future. Although, results for gastrointestinal adverse reactions were not significant, the reactions tended to be higher when lacritose was consumed and the sweetener had relatively high amount of lactose and erythritol which might cause some adverse reaction in long-term use; therefore, further studies are needed to evaluate the maximum tolerable dose of lacritose in order to investigate better about its secondary gastrointestinal effects. Also, the effect of lacritose on appetite and insulin response is not clear, yet.

Lacritose used during the study was in powder like sugar. In order to blind the participants, lacritose was similar to sucrose and glucose. But after approval of the advantage and its safety for individuals, it can be prepared in different formulations like sugar, like beverages, confections, and also pills/capsules in industrial phase.

In conclusion, blood glucose levels were significantly lower after ingestion of one 50g dose of lacritose; this is while the adverse reaction was not statistically different. Even though lacritose's energy content is nearly half of glucose and sucrose. Further studies with more study participants examining the long-term effects of lacritose on appetite, body weight and other metabolic markers of long-term glucose control are recommended.

Funding sourceThe study was financially supported by Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences and Health Services (grant no. 4259).

Authors’ contributionASA, RN, FK conceived the study. ASA and MAM carried out the study. Data analysis and interpretation were conducted by ASA and MAM. The first draft of the paper was written by MAM and ASA. All authors contributed to the study conception, design and drafting of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The present study was extracted from a MSc thesis approved by International Branch, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd Iran. The research executive team would like to warmly thank all the participants and the staff of Baqaipoor obesity clinic of Shahid Sadoughi University of medical Sciences. We also have to thank the research council of Nutrition and Food Security research center, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences for the scientific support of the present study.