A 56-year-old female patient with an unremarkable history was admitted to hospital in August 2009 for constitutional symptoms with a weight loss of 8kg over the previous year, early satiety, and epigastric pain treated with omeprazole and domperidone on an outpatient basis. Physical examination revealed hepatomegaly extending 3cm below the right costal margin and palpation of the spleen apex in the left hypochondriac region. Laboratory test results included: Hb, 11.3g/dL (<12g/dL); ESR, 73mm/h (>20mm/h); HbA1c, 6.7% (>5.7%); basal blood glucose, 117mg/dL (60–100mg/dL); LDH, 708 (>380U/L).

Fiberoptic gastroscopy showed a 3cm×4cm lesion extrinsically compressing the antrum. An abdominal CT scan revealed multiple focal hepatic lesions with characteristics of hypervascular metastasis affecting 70% of the liver, and a focal lesion in the tail of the pancreas that caused splenic vein thrombosis. Ultrasound-guided FNA of the liver disclosed hepatic metastases from a well differentiated, synaptophysin-positive neuroendocrine carcinoma. Ki67 and chromogranin A could not be tested in the sample. Octreoscan showed a positive activity of somatostatin receptors in the liver. Tissue from primary tumor could not be obtained, and a histological characterization was therefore not possible.

Based on a diagnosis of metastatic, well differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (NET), chemotherapy was started with streptozocin and adriamycin. Two days later, the patient was admitted to hospital for urinary tract infection and pain in the liver, and required dexamethasone. She had hyperglycemic decompensation, which was treated with subcutaneous insulin as a basal-bolus regimen, which was continued after discharge. A CT scan performed in April 2010 showed a significant decrease in the size and number of liver metastases, and a slight decrease in size of the pancreatic tail mass. Treatment was then started with octreotide LAR 30mg IM every four weeks.

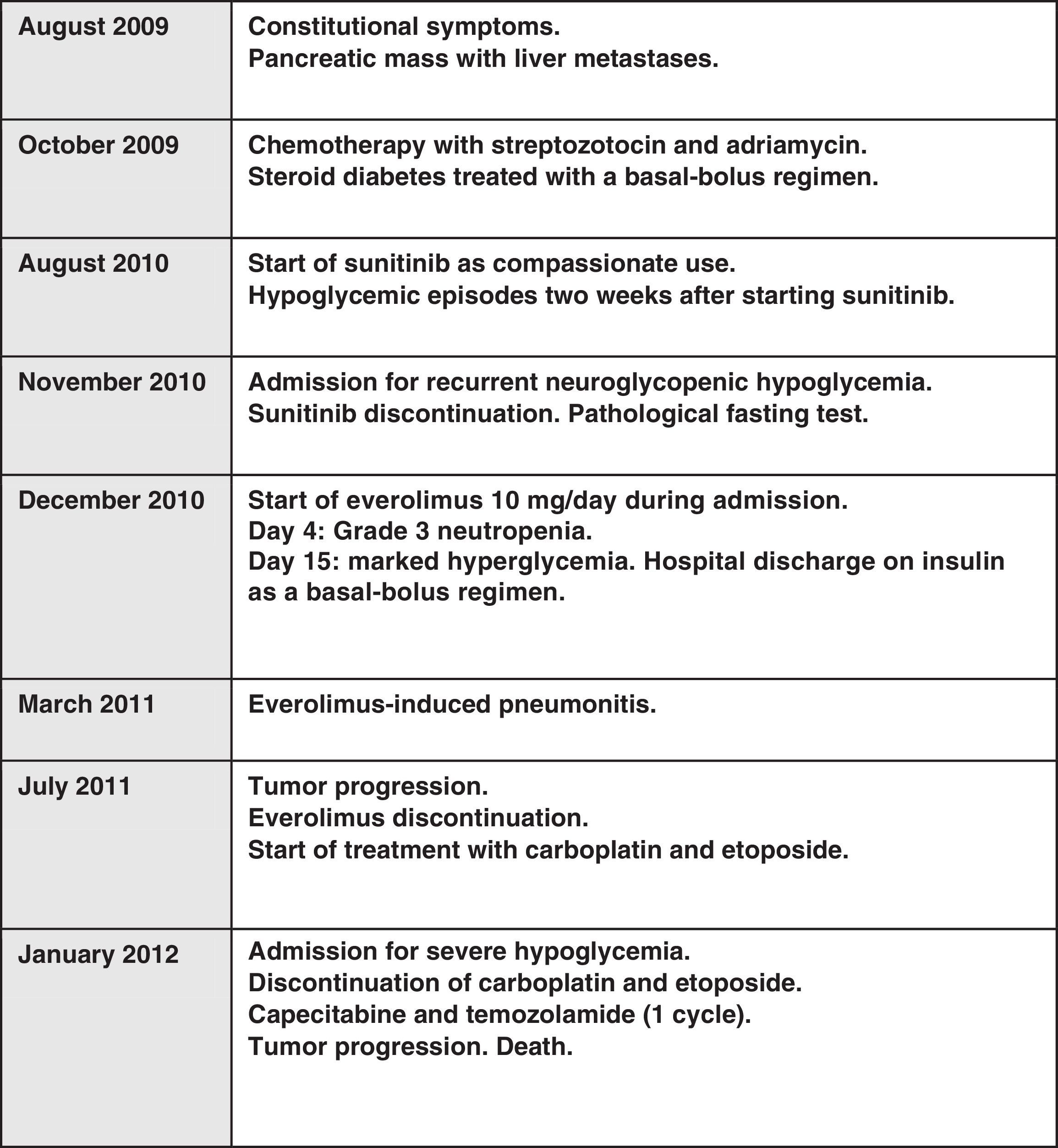

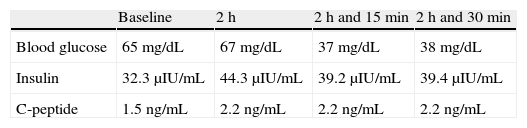

An abdominal CT performed in August 2010 showed a growth of the pancreatic lesion and an increased number and size of liver lesions. Treatment was started with oral sunitinib 37.5mg/day on a compassionate use basis, causing dysgeusia and constipation as toxic effects. Two weeks after sunitinib start, the patient experienced hypoglycemia, documented as an outpatient finding. In November 2010, the patient was admitted to the endocrinology department for difficult to control recurrent hypoglycemic episodes despite progressive fractionated diet, diazoxide up to 300mg/day, and prednisone 30mg/day. During admission, she required a continuous provision of 10% glucose. Sunitinib was discontinued due to its coinciding with the occurrence of hypoglycemia. A fasting test was performed, severe hypoglycemia and a biochemical pattern of glucose, insulin, and C peptide consistent with endogenous hyperinsulinism being found (Table 1). A urine drug screen ruled out the presence of metformin, repaglinide, glipizide, gliclazide, glibornuride, nateglinide, glimepiride, glibenclamide, and gliquidone. A malignant insulinoma was suspected as the first possibility. During the same admission, everolimus 10mg daily was added as a treatment for the primary tumor and for the management of severe refractory hypoglycemia with neuroglycopenic clinical signs. On the fourth day after the start of everolimus, the patient had neutropenia (600neutrophils/μL), and the dose was therefore decreased to 5mg/day. After the normalization of CBC on day 10 of treatment, the dose was increased to 10mg/day. Selective embolization of liver metastases was planned to control the symptoms and tumor disease. However, 15 days after the start of everolimus the patient experienced frank hyperglycemia which continued throughout the remainder of her admission.

The patient remained four months without hypoglycemia. However, she developed marked hyperglycemia as toxicity associated with everolimus and octreotide, which required insulin as a basal-bolus regimen. A new CT scan of the chest and abdomen performed in March showed new pulmonary infiltrates related to everolimus-induced pneumonitis and stability of the tumor disease. Three months later, the dose was decreased to 5mg/24h because of the radiographic progression of pulmonary infiltrates associated with everolimus.

In July 2011, eight months after the start of everolimus, the patient was readmitted for severe hypoglycemic episodes associated with the progression of the tumor disease at the pancreatic and hepatic level. Everolimus was discontinued and carboplatin and etoposide were started. A control CT did not show the prior pneumonic infiltrates. A new admission was required in January 2012 for severe hypoglycemic episodes with loss of consciousness difficult to manage in the outpatient setting. After assessment in the endocrinology department, treatment was started with diazoxide 300mg/24h as three divided doses, dexamethasone 2mg/8h, 50% dextrose as a continuous perfusion, maltose dextrin 500g in 1000mL at a rate of 40mL/h through nasogastric tube, and octreotide 30mg LAR every four weeks, despite which the patient experienced hypoglycemia with glucose levels less than 30mg/dL with severe neuroglycopenic symptoms. An initial cycle of capecitabine plus temozolamide was completed. The patient died soon afterwards from urinary sepsis and refractory hypoglycemia (Fig. 1).

The reported patient had a pancreatic NET with a possible change in tumor phenotype during the clinical course, as she experienced hypoglycemic episodes with severe symptoms one year after the diagnosis of an apparently non-functioning pancreatic tumor. Although the patient had previously experienced steroid hyperglycemia, she subsequently developed recurrent hypoglycemia. The use of hypoglycemic drugs was ruled out, and a fasting test revealed endogenous hyperinsulinism (detectable C-reactive peptide with very low glucose levels). The patient had previously been treated with sunitinib. Hypoglycemia has been reported as an adverse effect of this tyrosine kinase inhibitor whose specific pathophysiology is unknown, although it could be related to inhibition of c-kit (tyrosine kinase c-kit of CD117) and PDGFRβ (platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta). However, hypoglycemia persisted after sunitinib discontinuation, and increased in frequency and severity.

The management of progressive malignant insulinoma with severe recurrent hypoglycemia represents a true medical challenge. Symptom control is essential to improve patient quality of life, and multiple therapies have been used for this purpose with variable response. The treatment of progressive tumor disease may also be difficult, as few comparative studies are available and the various drugs are associated with a high toxicity. Less than 10% of patients with insulinoma experience distant metastases (in liver, bone, and lymph nodes). The median survival of these patients is less than two years.1

Treatments used include debulking surgery, therapies for liver disease (embolization, chemoembolization, radiofrequency ablation, laser-induced interstitial thermotherapy, selective internal radiotherapy using microspheres), interferon alpha, cytotoxic chemotherapy, or radionuclides. When possible, the resection of primary pancreatic tumor, even in the presence of liver metastases, may help control symptoms and increase survival.2

The combination of doxorubicin with streptozotocin, with or without 5-fluorouracyl, has traditionally been used as the first-line treatment with response rates up to 70%3–5 (toxicity: myocarditis, kidney or liver insufficiency, mucositis, asthenia, diarrhea and/or myelosuppression). Results have recently been achieved with temozolamide plus capecitabine as the first-line treatment for pancreatic NETs, including metastatic malignant insulinomas, achieving a median progression-free survival of 18 months, with a tumor response in 70% of patients.6

The molecular pathways implicated in sporadic malignant insulinomas are mostly unknown. Decreases in TSC2 (tuberous sclerosis protein 2) and PTEN (phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate 3-phosphatase) lead to activation of the mTOR pathway (mammalian target of rapamycin), which has been implicated in cell response in many tumors. All of these result in growth, proliferation, decreased apoptosis, and increased angiogenesis.7,8 Everolimus (RAD001, Affinitor®) is an inhibitor of the mTOR pathway which was shown to increase median survival from 4.6 to 11 months in a Phase III double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on 410 patients with low to intermediate grade NETs (the RADIANT 3 study).9 However, the number of patients with progressive malignant insulinoma included in that series was not reported. Everolimus is frequently associated with side effects including stomatitis, mouth sores, rash, diarrhea, neutropenia, anemia, asthenia, non-infectious pneumonitis, infections, and hyperglycemia, amongst others.

Everolimus may induce hyperglycemia by inhibiting insulin release by beta cells through the AMPK(5′-AMP-activated protein kinase)/c-Jun pathway, and maybe also by causing peripheral insulin resistance.10 Glucose control improvement appears to be independent, at least partly, of tumor mass changes, which supports a direct effect on insulin release/function.

Please cite this article as: Cuesta Hernández M, Gómez Hoyos E, Marcuello Foncillas C, Sastre Valera J, Díaz Pérez JÁ. Insulinoma maligno avanzado. Respuesta y toxicidad con everolimus. Endocrinol Nutr. 2014;61:e1–e3.