D-lactic acidosis is an uncommon cause of metabolic acidosis. Its incidence is unknown, but it is probably more common than usually thought.1D-lactic acidosis has been reported more frequently in recent years due to the increased survival rate of patients with short bowel syndrome (SBS) and to the development of home parenteral nutrition (HPN) programs.2

The case of a 39-year-old male patient, monitored by the nutrition unit of the endocrinology department of our hospital for 20 years due to SBS requiring HPN, is reported. His personal history included a traffic accident where he sustained an abdominal trauma that required massive bowel resection, leaving a left colon remnant and 15cm of jejunum.

Over the previous two years, the patient had complained of self-limited episodes consisting of ataxia, dysarthria, and limb incoordination lasting less than 24h. He had visited other centers, where the condition had been considered a vertiginous syndrome. In the three months prior to admission, both the frequency and duration of these episodes had increased until they were occurring weekly and were longer than 24h. Because of this clinical impairment, the patient was advised to attend our hospital when one of these episodes occurred.

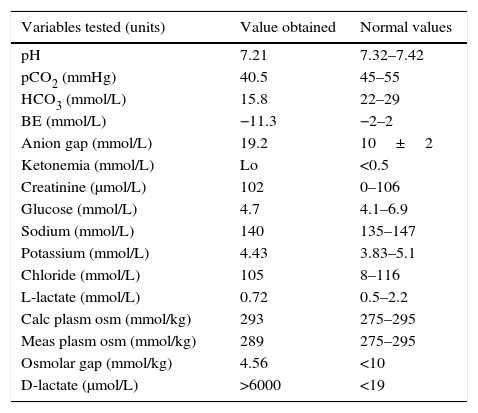

He attended our hospital with clinical signs of head instability, difficulty in speaking, and ataxia. A neurological examination revealed dysarthria, nystagmus, and unstable gait. Based on an initial diagnosis of central vertiginous syndrome, a CT scan of the head, MRI of the brain and an electroencephalogram were performed, with normal results. Laboratory tests requested showed that metabolic acidosis had increased the anion gap and the normal osmolar gap. His blood chemistry was otherwise unremarkable (Table 1). In this patient with a history of SBS and remnant colon showing encephalopathy and metabolic acidosis with an elevated anion gap for no apparent cause, D-lactic acidosis was suspected. A sample was therefore sent to an external laboratory, which reported a markedly increased D-lactate level (>6000μmol/L).

Laboratory measurement performed during an episode.

| Variables tested (units) | Value obtained | Normal values |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.21 | 7.32–7.42 |

| pCO2 (mmHg) | 40.5 | 45–55 |

| HCO3 (mmol/L) | 15.8 | 22–29 |

| BE (mmol/L) | −11.3 | −2–2 |

| Anion gap (mmol/L) | 19.2 | 10±2 |

| Ketonemia (mmol/L) | Lo | <0.5 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 102 | 0–106 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 4.7 | 4.1–6.9 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 140 | 135–147 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.43 | 3.83–5.1 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 105 | 8–116 |

| L-lactate (mmol/L) | 0.72 | 0.5–2.2 |

| Calc plasm osm (mmol/kg) | 293 | 275–295 |

| Meas plasm osm (mmol/kg) | 289 | 275–295 |

| Osmolar gap (mmol/kg) | 4.56 | <10 |

| D-lactate (μmol/L) | >6000 | <19 |

D-lactic acidosis was thus confirmed, and the patient was kept hydrated and given sodium bicarbonate by the intravenous route. An oral diet with a high protein content was also started, and slow absorption carbohydrates (CHs) were subsequently reintroduced with adequate tolerance. Oral antibiotic therapy with metronidazole for seven days was also given, with the disappearance of the clinical signs. The patient was discharged home with no symptoms.

After a year of follow-up, the patient remains paucisymptomatic on a diet with controlled slow absorption CHs and restricted fast absorption CHs, a probiotic supplement producing no D-lactate, Bivos® (Lactobacillus rhamnosus), and antibiotic therapy for one week monthly. No new disabling episodes have occurred, but the patient occasionally experiences mild symptoms after dietary transgressions.

D-lactic acidosis does not only appear in SBS. It may also occur after bariatric surgery, the provision of propylene glycol, or diabetic ketoacidosis.3 L-lactate is the main isomer in humans, and D-lactate may occur in low concentrations from the metabolic pathway of glyoxilase after fermented food is taken.4 D-lactate is metabolized through the enzyme D-2 hydroxyacid dehydrogenase (D-2-HDH), which is mainly found in the kidney and liver and whose activity is decreased in a state of acidosis.1,4

In SBS, D-lactate formation occurs due to the massive arrival in the colon of undigested CHs which are fermented by bacterial flora, leading to the increased production of organic acids and the acidification of the intestinal environment. This promotes the growth of acid-fast bacteria that generates greater amounts of D-lactate and L-lactate and inhibits D-2-HDH, thus creating a vicious cycle in which the production of D-lactate exceeds the capacity to remove it.4

Symptoms appear from a few months to several years after the underlying disease is established,5 and consist of episodic encephalopathy typically occurring after the intake of food rich in CHs, especially fast absorption CHs.6 The most common symptoms include dysarthria, ataxia, gait disturbance, or motor incoordination. Headache, visual disturbance, seizure, or coma may also occur. The pathophysiological mechanism is not fully known,7 but plasma D-lactate levels do not correlate to symptom severity, so that other organic acids may act as false neurotransmitters.4

Diagnosis is often delayed, and requires a high index of suspicion. D-lactic acidosis should be suspected in patients with SBS and an intact colon who have episodic neurological symptoms and experience metabolic acidosis not otherwise explainable. Metabolic acidosis with a high anion gap is typical, but hyperchloremic acidosis may occur. The measurement of plasma D-lactate levels requires a special test containing D-lactate dehydrogenase, which is not available in most clinical laboratories. It is a challenging diagnosis because of the episodic nature of the condition, and it is essential to investigate the patient's clinical history to establish the relationship between the symptoms and the intake of CH-rich food.1,4

In the acute phase, treatment is based on water and electrolyte replacement, the use of sodium bicarbonate, and the suppression of oral/enteral CHs. Oral antibiotics with poor intestinal absorption such as clindamycin, vancomycin, neomycin, or metronidazole are used. In severe cases, hemodialysis has been successfully used.1,4

The long-term effectiveness of the treatment is limited.1 Exogenous enteral/oral CH sources, especially simple sugars, should be reduced. Periodic antibiotic cycles based on the antimicrobial susceptibility of germs present in fecal cultures have been proposed.1,8 The use of probiotics is controversial, and no conclusive data are available.4 When the above measures fail, surgical options may be considered, including bowel lengthening, small bowel transplant and, in extreme cases, total colectomy.2,5

D-lactic acidosis is a rare condition with a negative impact on the quality of life of patients with SBS. It is usually difficult to detect, and clinicians should keep it in mind in order to be able to make an early diagnosis and provide adequate treatment.

AuthorshipAll the authors have substantially contributed to one or more of the following: study conception and design, the collection of information, data analysis and the interpretation, and approval of the final version of the manuscript for submission to the journal.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Planas-Vilaseca A, Guerrero-Pérez F, Marengo AP, Lopez-Urdiales R, Virgili-Casas N. Acidosis por D-lactato: una causa inusual de acidosis metabólica. Endocrinol Nutr. 2016;63:433–434.