A 42-year-old male, active smoker, homosexual, with a history of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) stage A1 since 2009, currently on monotherapy with darunavir/cobicistat with good viroimmunological control (<20copies/ml and 750 CD4 lymphocytes/mm3, respectively), and syphilis treated correctly in 2015. He went to an outpatient clinic for symptoms of two months’ evolution consisting of a large number of watery diarrhoeal stools without pathological products, which did not relent during night-time rest and were unrelated to intake or fasting, together with abdominal cramps. He denied having fever, nausea, vomiting or rectorrhagia, as well as recent risky sex. In the analysis performed, there were no alterations to haematological parameters; renal function, liver parameters and ions were normal, as was thyrotropin. Of note was elevated IgE (2.699IU/ml). Syphilis serology: RPR negative, total antibodies and TPHA positive. Study of eggs and parasites in faeces obtained with 3 samples was negative, as were stool culture, antigen determination of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia spp., anti-transglutaminase antibodies, HLA-DQ2/DQ8, anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies and faecal calprotectin. Computed tomography of the abdomen showed no pathological findings. An informed normal colonoscopy was performed, taking biopsies of the colonic mucosa.

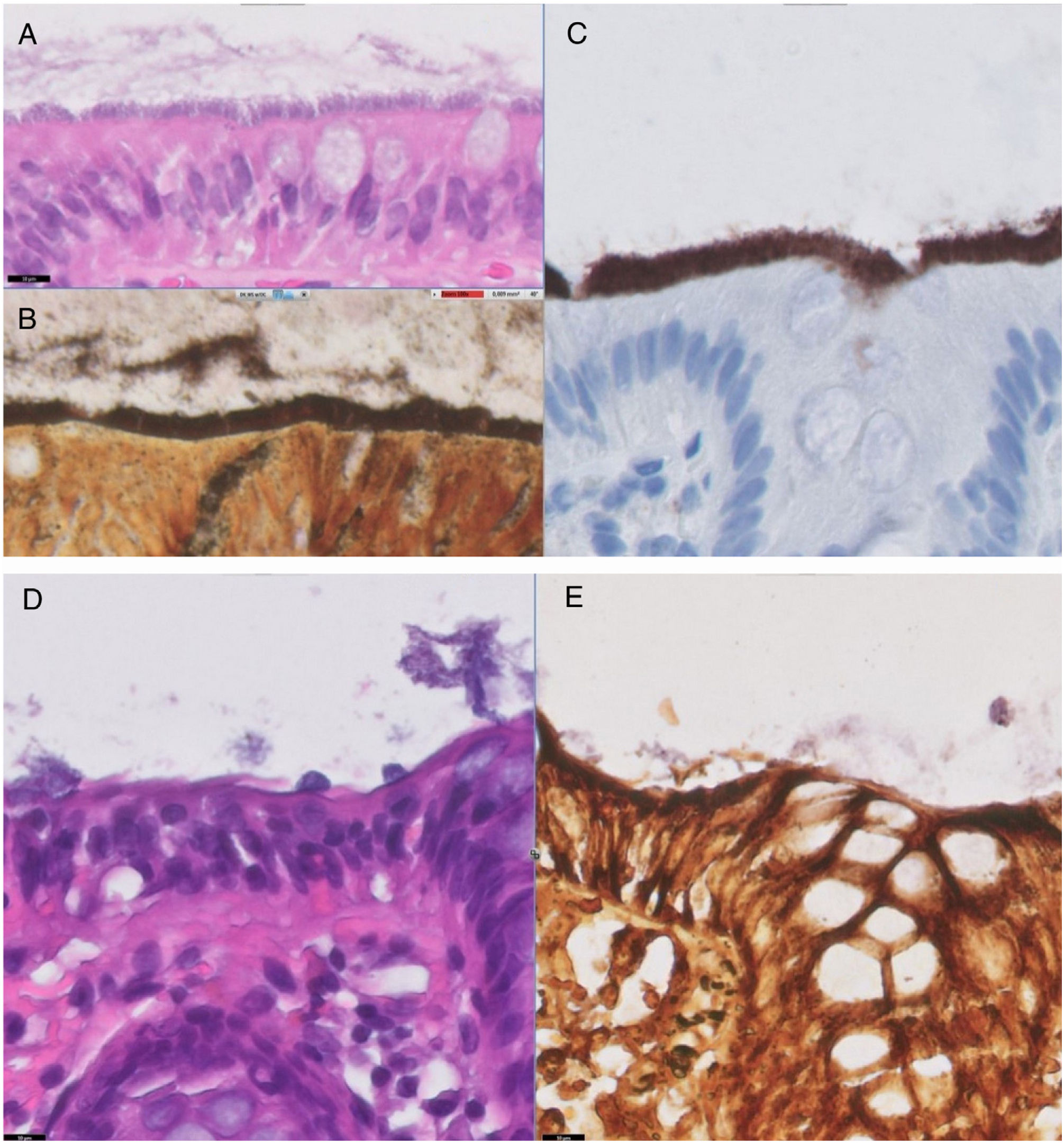

EvolutionThe pathological result was a brush image along the entire border of the intestinal epithelium that was stained with Warthin–Starry staining (Fig. 1A and B), the standard staining for spirochete detection. Staining with polyclonal anti-Treponema pallidum antibody was performed due to immunohistochemistry in the colonic mucosa that was positive due to the existing cross reaction with the genus Brachyspira,1 all suggestive of intestinal spirochetosis (Fig. 1C). Treatment with metronidazole was initiated at doses of 500mg/3 times a day/for 10 days, with partial improvement, but persistence of abdominal symptoms and diarrhoea, so a second cycle was administered. Following this, the patient improved until he was asymptomatic and the biopsies obtained in the control colonoscopy (Fig. 1D and E) revealed signs of mild chronic lymphoplasmocytic colitis without signs of spirochetosis (Warthin–Starry negative).

The microscopic study with haematoxylin–eosin (A) shows a colonic mucosa with a basophilic layer that corresponds to the strip of microorganisms on the luminal surface of the colonic epithelium. Image (B) corresponds to the Warthin–Starry histochemical staining, revealing microorganisms stained with silver impregnation on the luminal surface of the colonic epithelium, corresponding to spirochetes. Image (C) shows the positive immunohistochemical staining for the antitreponema antibody on the luminal surface of the colonic epithelium. After treatment, image (D) (haematoxylin–eosin) shows a colonic mucosa without the presence of the basophilic layer on the luminal surface of the colonic epithelium. Image (E) confirms the absence of microorganisms with Warthin–Starry histochemical staining.

Intestinal spirochetosis, initially described in 1967,2 consists of a colonization of the apical membrane of the colonic mucosa and the appendix by spirochetes of the genus Brachyspira, with these two species, Brachyspira aalborgi and Brachyspira pilosicoli,3 being the main ones responsible for infection in humans, although their main reservoirs are other mammals (pigs, primates, etc.) and birds (chickens), especially for B. pilosicoli.4

Its prevalence varies depending on the geographical area, being 1.1–5% in developed countries and up to more than 30% in developing countries.5 It is more common in men who have sex with men and are HIV positive, suggesting a faeco-oral and sexual transmission.4,5

In a high percentage of cases it is asymptomatic, and constitutes an endoscopic finding; however, it can cause nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, rectorrhagia,6 weight loss and, very rarely, hepatitis and bacteraemia.7 Coinfection with other microorganisms such as H. pylori, Shigella, Giardia or Salmonella is common.7

Colonoscopy does not usually show macroscopic abnormalities, although erythema, pustules and even ulcers can be seen, which can simulate inflammatory bowel disease.8,9 Being slow-growing anaerobic bacteria, culture is not usually useful and they are not visible by Gram staining, so the diagnosis is made by identifying spirochetes at the border of the intestinal epithelium by haematoxylin–eosin and Warthin–Starry staining, producing an image called “false epithelial barrier” or “false brush border”.10 Sometimes there are signs of mucous inflammation. The application of molecular techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) allows the identification of the species.6,10

In asymptomatic cases due to a casual finding, antibiotic treatment would not be indicated. In symptomatic cases, macrolides, clindamycin and metronidazole have been used,5 with the latter being the most used and considered the drug of choice, although there is no evidence in this regard. The duration of treatment is not stipulated, nor is the dose,6 although 500mg/every 6 or 8h for 5–10 days is normally used. Recurrence is frequent, and several cycles may be required for its elimination. The improvement of the symptoms and the disappearance of histological lesions in control biopsies are the best indicators of its having been cured.

FundingThe authors declare that they have not received funding to carry out this work.

Please cite this article as: Rosales-Castillo A, Hidalgo JL, Tenorio CH. Una causa infrecuente de diarrea crónica. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2020;38:240–242.