To study the characteristics of HIV infection in the gypsy (Roma) population in Spain, as compared with those of the Caucasian, non-gypsy majority.

DesignCross-sectional, historical cohort study from the Spanish VACH Cohort.

MethodsPatients attending VACH clinics between 1 June 2004 and 30 November 2004 were classified according to their racial and ethnic origin as “gypsies”, Caucasian non-gypsy Spanish natives (CNGN), and “other” (the last being excluded from this study). Their sociodemographic and clinico-epidemiological characteristics were compared, as well as the Kaplan–Meier curves of time to AIDS, or death, or disease progression (either of the 2 outcomes).

Results4819 (48%) of 10,032 cases included in the VACH database were eligible: 210 (4.2%) were gypsies and 4252 (84.8%) were CNGN. Differences were observed in age, household, academic, inmate, marital, and employment history. Injecting drug use had been the most frequent mechanism of transmission in both groups, but to a greater extent among gypsies (72% versus 50%; P<0.000). Sex distribution, CD4 cell counts, and viral loads at the first visit were similar in the 2 groups, as was the percentage of patients with previous AIDS, percentage receiving antiretrovirals, and percentage subsequently starting antiretroviral therapy. Up to 1 April 2005, 416 new AIDS cases and 85 deaths were recorded. The percentage of these outcomes did not differ between groups, but log-rank test showed a shorter time to AIDS and disease progression among gypsies.

ConclusionsThe sociodemographic characteristics of gypsies, the largest minority in the VACH Cohort, show differences relative to those of CNGN. HIV-related outcomes suggest that gypsies have a poorer prognosis.

estudiar las características de la infección por el VIH en gitanos en España, en comparación con las de la mayoría caucásica no gitana (CNG).

Métodosestudio transversal y de cohortes históricas en la Cohorte VACH. Clasificamos a los pacientes que acudieron a las clínicas participantes en VACH entre el 1 de junio de 2004 y el 30 de noviembre de 2004 de acuerdo a su raza y etnia, como «gitanos», «nativos españoles CNG» u «otros» (estos, excluidos de este estudio). Comparamos sus características sociodemográficas y clinicoepidemiológicas, así como sus curvas de Kaplan–Meier del tiempo hasta sida, muerte o progresión de la enfermedad (cualquiera de ambos).

Resultados4819 (48%) de 10.032 casos recogidos en la base de datos de VACH fueron incluidos en el estudio: 210 (4,2%) eran gitanos y 4.252 (84,8%) eran nativos CNG. Observamos diferencias en sus distribuciones por edad, domicilio, estudios, antecedentes penales, situación laboral y marital. La inyección de drogas había sido el mecanismo de transmisión del VIH más frecuente en los dos grupos, pero más marcadamente en los gitanos (72% frente a 50%; p<0,000). La distribución por sexos, los recuentos de linfocitos CD4 y las cargas virales en la primera visita fueron similares en ambos grupos, así como las proporciones de pacientes con sida previo y las de quienes estaban ya en, o iniciaron entonces, tratamiento antirretroviral. Hasta el 1 de abril de 2005 se registraron 416 nuevos casos de sida y 85 muertes. La proporción de ambos resultados fue similar en ambos grupos, pero la prueba del rango logarítmico demostró una evolución más rápida a sida y a progresión de la enfermedad para los gitanos.

ConclusionesLos gitanos constituyen la minoría étnica más numerosa en la Cohorte VACH. Observamos diferencias en sus características sociodemográficas en relación con las de los nativos españoles CNG. Las variables de evolución relacionadas con el VIH sugieren que los gitanos tienen peor pronóstico.

The gypsy (Roma) population is the largest ethnic minority in Spain and in several countries across Southeastern Europe. Despite this considerable presence, there are no official data on their existence, not to mention particular aspects of their socioeconomic or health situation.

Investigation elsewhere has demonstrated that socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic differences are major determinants of disparity in the quality of health care and of worse health outcome.1 In Europe, the assumption that equality under the law assures equality in health and health care protracts the development of comprehensive investigation.2 In addition, the identification of minorities for whatever purpose is viewed by many as further stigmatizing already marginalized groups.

In this scenario, the HIV epidemic and its impact on the gypsy minority represents a challenging subject. Scattered reports suggest that this population may be at increased risk for viral infection, both enteric and blood borne.3–5 In addition, HIV infection interacts with other social stigmata to increase any degree of marginality.

However, the existence of a problem can be anticipated, and the search for solutions starts by identifying its terms and magnitude. This study investigates whether there are any differences in the characteristics of the HIV epidemic between gypsies and Caucasian non-gypsy Spanish natives in our area, and to what extent these differences might influence the outcome of HIV infection.

Patients and methodsThe aims and methods of the VACH Study Group have been presented elsewhere.6 Briefly, the group was established in 2000 by an association of clinicians working in 16 (currently, 19) public hospitals throughout Spain who shared a common software tool, AC&H®, which has undergone 6 major operative updates. The fourth one, performed in June 2004, uploaded a racial and ethnic classification selected from the Dictionary of Demographic and Reproductive Health Terminology of the United Nations Population Information Network.7

On this basis, we performed a cross-sectional analysis of the clinical and epidemiological characteristics at the time of the first visit to a VACH-associated clinic, of HIV-infected patients of gypsy ethnic origin as compared with those of HIV-infected Caucasian non-gypsy Spanish natives (CNGN). Additionally, we collected historical cohort data on the risk of progression of HIV diseases according to this ethnic classification.

To be included in the VACH Cohort, a patient must have documented HIV infection and have attended at least 1 visit to any VACH-associated clinic after 1 January 1997. Patients who came to the clinics between 1 June and 30 November 2004 were asked to give informed consent for their data to be used in this study. We updated their racial and ethnic information at each site, and subsequently, in the VACH central database. Non-Caucasian patients and non-Spanish Caucasians were excluded from the study, so that all remaining patients would be classified as either “gypsy” or “CNGN”.

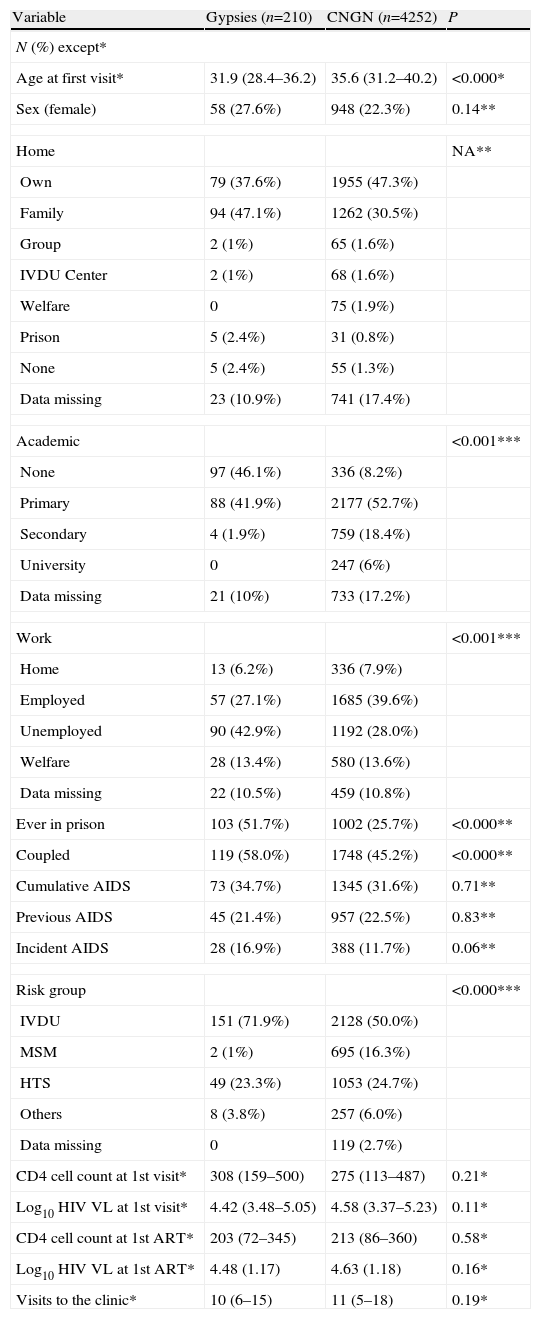

The variables selected for the cross-sectional analysis and their categories are presented in Table 1, together with their results. We defined “cumulative AIDS”, “previous AIDS”, and “incident AIDS”, respectively, as an AIDS-defining disease previous to or during follow-up, an AIDS-defining disease prior to inclusion in the cohort, and an AIDS-defining disease after inclusion in the cohort. We defined “new HIV diagnoses” as patients with HIV infection diagnosed in the preceding 3 months who had not attended another specialized HIV clinic previously. The percentage of patients who had ever initiated ART and those who had started it after inclusion were also studied. The longitudinal analysis is described below.

Characteristics of patients, classified according to their ethnic origin.

| Variable | Gypsies (n=210) | CNGN (n=4252) | P |

| N (%) except* | |||

| Age at first visit* | 31.9 (28.4–36.2) | 35.6 (31.2–40.2) | <0.000* |

| Sex (female) | 58 (27.6%) | 948 (22.3%) | 0.14** |

| Home | NA** | ||

| Own | 79 (37.6%) | 1955 (47.3%) | |

| Family | 94 (47.1%) | 1262 (30.5%) | |

| Group | 2 (1%) | 65 (1.6%) | |

| IVDU Center | 2 (1%) | 68 (1.6%) | |

| Welfare | 0 | 75 (1.9%) | |

| Prison | 5 (2.4%) | 31 (0.8%) | |

| None | 5 (2.4%) | 55 (1.3%) | |

| Data missing | 23 (10.9%) | 741 (17.4%) | |

| Academic | <0.001*** | ||

| None | 97 (46.1%) | 336 (8.2%) | |

| Primary | 88 (41.9%) | 2177 (52.7%) | |

| Secondary | 4 (1.9%) | 759 (18.4%) | |

| University | 0 | 247 (6%) | |

| Data missing | 21 (10%) | 733 (17.2%) | |

| Work | <0.001*** | ||

| Home | 13 (6.2%) | 336 (7.9%) | |

| Employed | 57 (27.1%) | 1685 (39.6%) | |

| Unemployed | 90 (42.9%) | 1192 (28.0%) | |

| Welfare | 28 (13.4%) | 580 (13.6%) | |

| Data missing | 22 (10.5%) | 459 (10.8%) | |

| Ever in prison | 103 (51.7%) | 1002 (25.7%) | <0.000** |

| Coupled | 119 (58.0%) | 1748 (45.2%) | <0.000** |

| Cumulative AIDS | 73 (34.7%) | 1345 (31.6%) | 0.71** |

| Previous AIDS | 45 (21.4%) | 957 (22.5%) | 0.83** |

| Incident AIDS | 28 (16.9%) | 388 (11.7%) | 0.06** |

| Risk group | <0.000*** | ||

| IVDU | 151 (71.9%) | 2128 (50.0%) | |

| MSM | 2 (1%) | 695 (16.3%) | |

| HTS | 49 (23.3%) | 1053 (24.7%) | |

| Others | 8 (3.8%) | 257 (6.0%) | |

| Data missing | 0 | 119 (2.7%) | |

| CD4 cell count at 1st visit* | 308 (159–500) | 275 (113–487) | 0.21* |

| Log10 HIV VL at 1st visit* | 4.42 (3.48–5.05) | 4.58 (3.37–5.23) | 0.11* |

| CD4 cell count at 1st ART* | 203 (72–345) | 213 (86–360) | 0.58* |

| Log10 HIV VL at 1st ART* | 4.48 (1.17) | 4.63 (1.18) | 0.16* |

| Visits to the clinic* | 10 (6–15) | 11 (5–18) | 0.19* |

CNGN: Caucasian non-gypsy natives; IVDU: intravenous drug use; MSM: men who had sex with men; HTS: heterosexual; NA: not applicable (5 boxes had expected values lower than 5; see text for pairwise analyses); ART: antiretroviral treatment; HIV VL: HIV plasma viral load CD4+ counts: in cells/μL. *Quantitative variables are represented as the median and interquartile range, and corresponding P values were obtained by the Mann–Whitney U test. All remaining variables are represented as frequency and (percentage) and **P values are derived from the Fisher exact test or ***χ2 test.

We present summary statistics of the variables listed in Table 1, broken down by study group, as the median and interquartile range for quantitative variables and the percentage with 95% confidence interval (95% CI), when appropriate, for categorical variables. The homogeneity of the distribution of these variables in the study groups was determined by the Mann–Whitney U test (quantitative variables) or the χ2 and Fisher exact tests (qualitative variables). Estimates of the differences between means with the 95% CI and odds ratios (OR) with the 95% CI are presented when the additional information they provided was regarded as appropriate.

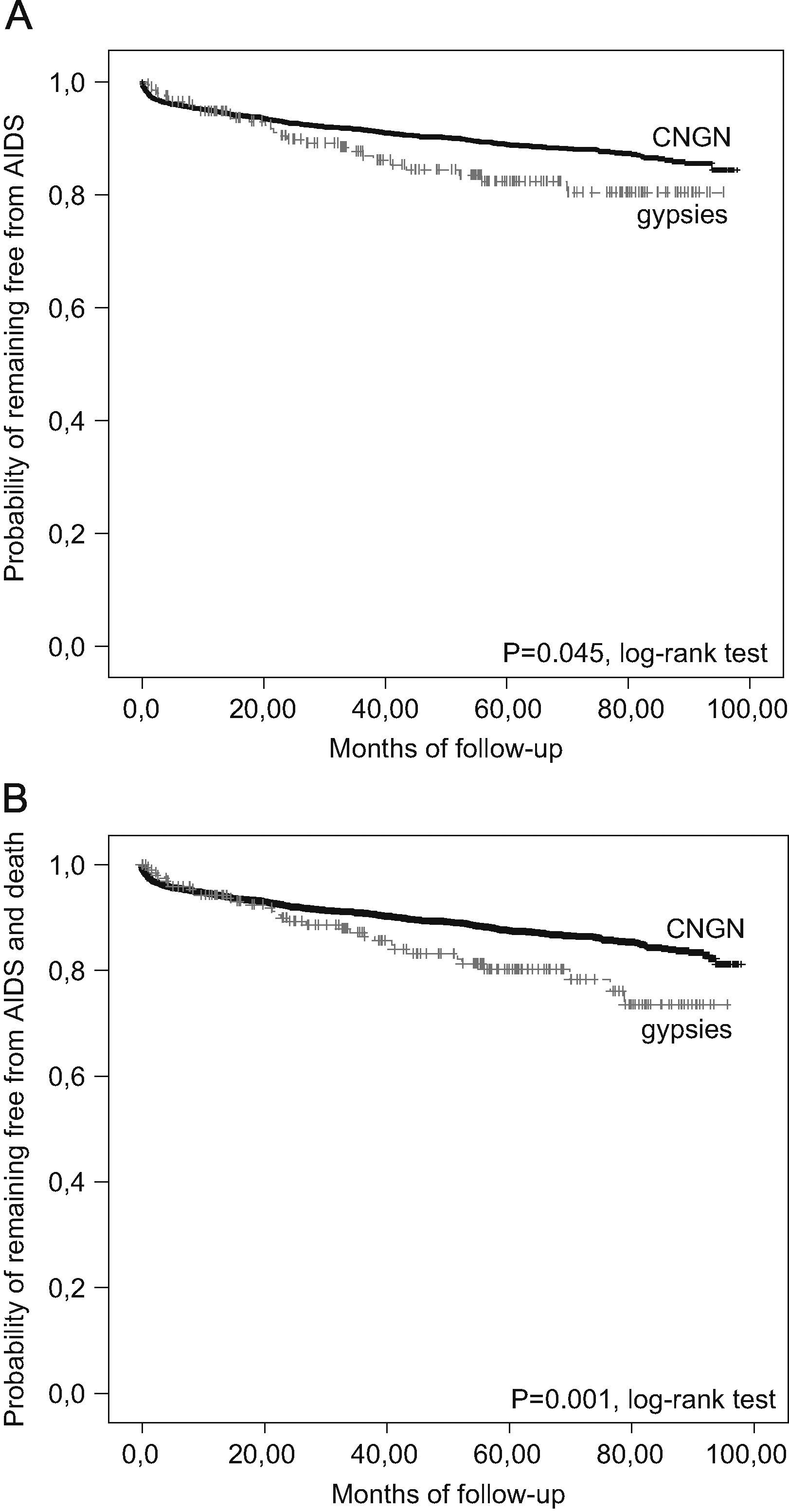

Kaplan–Meier curves were constructed for the survival analysis, with the following separate outcomes: (a) disease progression (defined as the occurrence of a first diagnosis of AIDS or death from any cause), (b) first diagnosis of AIDS, and (c) death. Follow-up calculations used the date of the first visit to the VACH-associated clinic as the initial date. Possible differences between the study groups were tested with a log-rank test. Incidence rates (IR), calculated for each of the 3 outcomes and reported as cases per 100 patient-years (C% PY) were obtained by dividing the total number of recorded outcomes by the accumulated number of patient-years (sum of months that each patient had remained on follow-up from his/her first visit up to whatever date occurred first among the following possibilities: study closure, pre-defined loss to follow-up, or outcome of interest, divided by 12), and multiplying by 100, both in each category. Finally, we used Cox proportional hazards models to adjust for the imbalanced distribution of several prognostic variables regarding their influence on the probability of HIV disease progression, as defined above. CD4 cell counts were modelled as a continuous variable, as the log10 transformation, and as a categorical variable (categories defined within each 50cell/μL additional increase and 100cell/μL increase).

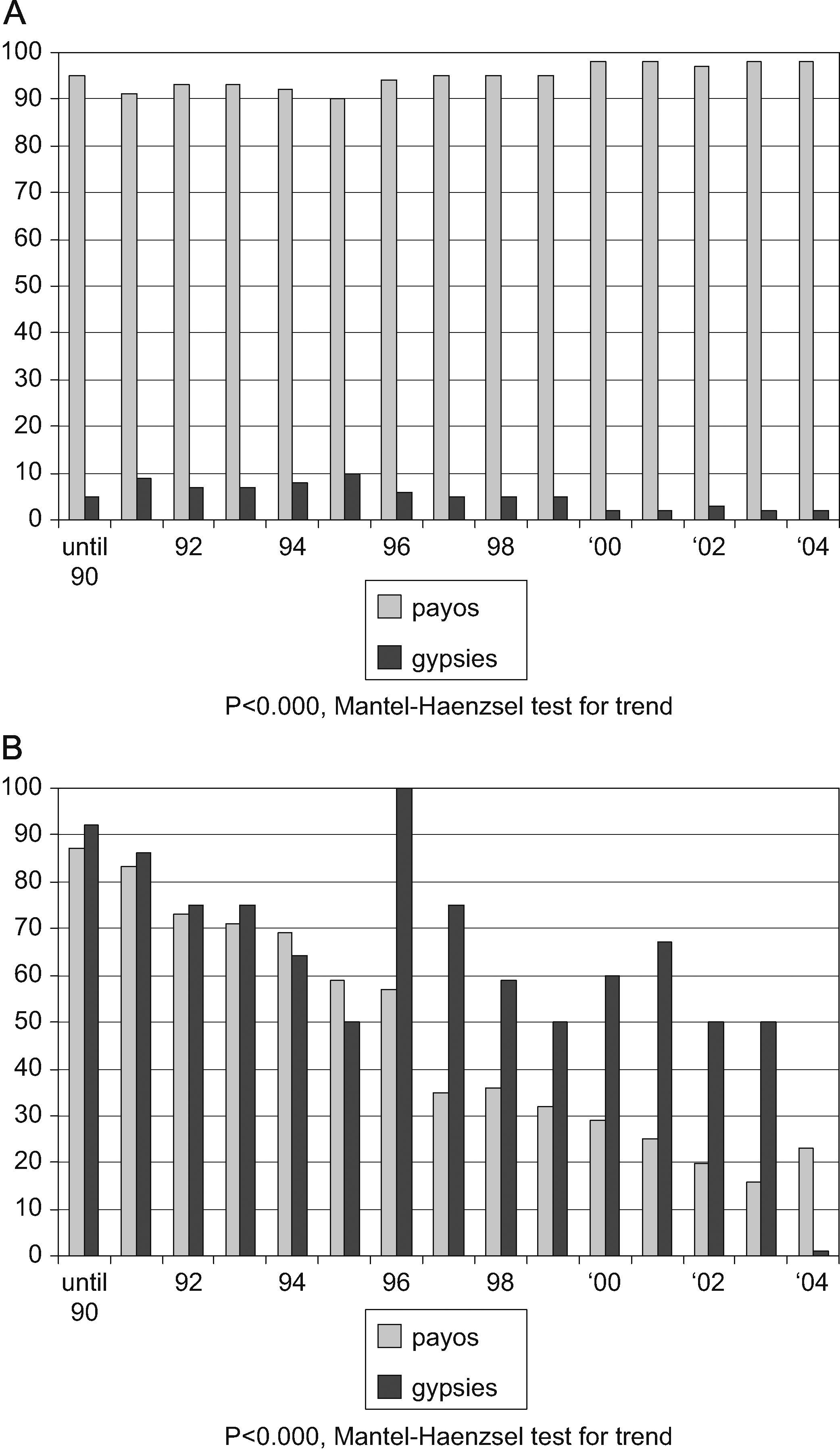

ResultsBy December 2004, 10,032 patients had been included in the VACH Cohort database. Among them, 4816 (48%) had at least one visit at a VACH-associated clinic in the pre-defined period; hence, their racial/ethnic data had been updated and they were eligible for participation. Among these candidates, 4252 (84.8%) were CNGN, 210 (4.2%) were gypsies, and 354 (11%) belonged to other ethnic groups or nationalities and were excluded (202 South Americans of different ethnic groups, 108 black individuals, 33 from Arabic countries, and 11 from the Far East). Newly diagnosed cases of HIV infection in gypsies significantly decreased as a percentage of the total number of new diagnoses included in the cohort along the period studied (Fig. 1A).

Temporal trend in the diagnoses of HIV infection and in cases attributed to an intravenous drug use-related mechanism of transmission (IVDU), among gypsies and Caucasian non-gypsy natives (CNGN) in Spain, 1997–2004: (A) Percentage of all cases of the diagnoses, according to ethnic origin. (B) Percentages of cases attributed to IVDU, according to ethnic origin.

Table 1 presents a summary of the most relevant clinico-epidemiological characteristics of the 4462 patients. One-fourth of the total was women, with no differences between gypsies and CNGN, although the latter were a significantly older group. Socioeconomic variables (academic, employment, private home, and inmate history) consistently showed lower achievements for gypsies. In contrast, the most representative clinico-epidemiological variables (CD4 cell count, HIV plasma viral load, and previous AIDS diagnosis) were remarkably similar between gypsies and CNGN at the first visit. Gypsy patients were less likely to live in a home of their own (OR: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.45–0.79) or be admitted to a shelter or welfare facility (OR: 0; 95% CI: 0–0.89), but there were no differences in the percentage who came from a prison, their families’ home or centers for intravenous drug users.

Intravenous drug use (IVDU) was the most common mechanism for HIV transmission in both groups over the study period as a whole, but was still significantly more common among gypsies. In addition, when broken down by calendar year, there was a significant decline in the percentage of intravenous drug-related cases in both gypsies and CNGN, but the decline was steeper among the latter (Fig. 1B).

Median follow-up (and interquartile range) was 1533 days (694–2124) for gypsies and 1505 days (680–2221) for CNGN (P=0.59, U test). Although the percentage of patients who developed a new AIDS-defining complication did not differ between the study groups, the time to the event was significantly shorter for gypsies. Incidence rates for gypsies and CNGN, respectively, were 3.9 and 2.6 cases per 100 patient-years (C% PY); relative risk (RR): 1.49; 95% CI: 1.02–2.16; P=0.0447, Fig. 2A). The percentage of deaths and time to death was similar between gypsies and CNGN (IR, respectively, 0.84 and 0.53 C% PY; RR: 1.59; 95% CI: 0.62–3.79; P=0.255), but the time to HIV disease progression showed a significant difference favoring CNGN (IR for gypsies and CNGN: 4.6 and 2.95 C% PY; RR: 1.56; 95% CI: 1.07–2.26; P=0.017, Fig. 2B). A trend was found for CNGN to ever initiate antiretroviral treatment (ART) more frequently than gypsies do (85% versus 77%; OR: 1.40; 95% CI: 0.99–1.97; P=0.058). A non-significant higher percentage had done so before inclusion in the cohort (24% versus 19%; OR: 1.19; 95% CI: 0.72–1.83; P=0.33) and the same was true for the prospective follow-up (77% versus 72%; OR: 1.21; 95% CI: 0.92–1.88; P=0.14).

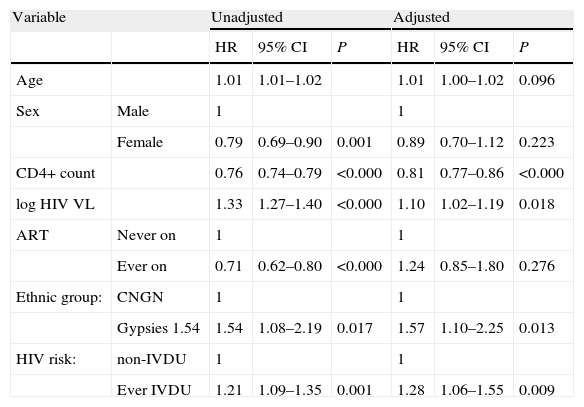

In a Cox regression model, ever being on ART was associated with longer time to disease progression when it was included as the only covariate, but this association disappeared in the final multivariate model. Other variables associated with disease progression in the crude analysis are presented in Table 2, together with the results of the final model. The CD4+ cell count was the strongest predictor of progression, even after adjusting for HIV plasma viral load and ART. More surprisingly, gypsies had a poorer prognosis than CNGN also after adjusting for ART and IVDU (and the remaining prognostic variables). When CD4 cell counts were modelled as the log10 transformation, age remained significantly associated with disease progression in the multivariate model (OR: 1.013, 95% CI: 1.002–1.024 per year older). Results for the remaining variables tested were notoriously similar, independently of how CD4 cell counts were modelled. We chose to present this variable as 100cell/μL-increment categories because of their intuitiveness and direct clinical correlation.

Factors associated with HIV disease progression (AIDS or death) in unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazards models.

| Variable | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Age | 1.01 | 1.01–1.02 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 0.096 | ||

| Sex | Male | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 0.79 | 0.69–0.90 | 0.001 | 0.89 | 0.70–1.12 | 0.223 | |

| CD4+ count | 0.76 | 0.74–0.79 | <0.000 | 0.81 | 0.77–0.86 | <0.000 | |

| log HIV VL | 1.33 | 1.27–1.40 | <0.000 | 1.10 | 1.02–1.19 | 0.018 | |

| ART | Never on | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Ever on | 0.71 | 0.62–0.80 | <0.000 | 1.24 | 0.85–1.80 | 0.276 | |

| Ethnic group: | CNGN | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Gypsies 1.54 | 1.54 | 1.08–2.19 | 0.017 | 1.57 | 1.10–2.25 | 0.013 | |

| HIV risk: | non-IVDU | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Ever IVDU | 1.21 | 1.09–1.35 | 0.001 | 1.28 | 1.06–1.55 | 0.009 | |

HR: hazard ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

Age OR, per 1 year increase.

CD4+ count OR, per 100cells/μL increase.

HIV VL: HIV plasma viral load. OR, per 1 log10 increase.

ART: antiretroviral treatment.

IVDU: intravenous drug use.

The unadjusted results were obtained from Cox models with the specified variable as the only covariate. The adjusted results were those of a Cox model with all the variables as covariates (Wald, forward).

The gypsy population is the largest ethnic minority among HIV-infected patients registered in the Spanish VACH Cohort. This is consistent with the hypothesis that this group constitutes the largest ethnic minority living in Spain, but could also be an indication that the HIV epidemic has stricken them particularly hard through the high prevalence of IVDU observed in this population in scattered reports.8,9

The transmission of HIV through heterosexual contact seems to have reached a level in gypsies similar to that seen in CNGN. However, the association with IVDU, characteristic of Spanish HIV epidemics in the earlier and middle years,10 seems to have been significantly stronger for gypsies. This population seems to have shared in the progressively decreasing percentage of IVDU-related new HIV diagnoses reported in recent years, but to a lesser extent than in CNGN. Thus, the percentage of gypsies within new diagnoses of HIV infection has significantly decreased along the years, as IVDU has become a less predominant mechanism for HIV transmission in Spain (Fig. 1).

In our cohort, HIV disease progressed faster to AIDS (and to AIDS or death) in gypsies than in CNGN. Differences in a wide array of intermediate variables are often found in relation to race or ethnic origin. Nonetheless, differences in the rates of disease progression have been only exceptionally reported.11,12 In the present study, ethnic origin remained associated with an increased risk of progression after adjusting for other prognostic variables.

Markers of lower socioeconomic status are associated with a poorer prognosis of HIV infection, but their relationship with race or ethnic group have not been reported in related studies.13–16 We found a trend towards restricted prescription of ART to gypsies, as compared with CNGN. However, even though ART prescription was associated with a decreased risk of disease progression in the univariate analysis, the association disappeared in the multivariate model, while ethnicity remained in the model. In the United States, differences in drug prescription according to race are observed more commonly than differences in outcome.17–21 We found no parallel information from countries with universal health care coverage such as ours. Wood et al15 found a gradient of HAART prescription according to socioeconomic level in Canada, and data from European cohorts also suggest that there is a potential for biased HAART prescription related to surrogate markers of lower socioeconomic status in countries with a universal healthcare system.13,22 Our data do not enable clarification of whether this trend towards differing ART prescription is mainly due to the patient's or the physician's decision.

A biological basis for the difference in outcomes in our cohort cannot be excluded, since differential genetics and genetically-based diseases are well recognized in gypsies.23 However, Roma people are more notorious for their sociocultural peculiarities (hence, their classification as an ethnic group), many of which have been repeatedly reported, as in this study. We believe that the search for reasons to explain the difference in outcomes should start on that basis.

In the background described, we suggest that “initiating” HAART is a just surrogate marker and not an optimal one, for “being” on HAART. Unfortunately, in the VACH Study Group we have not yet found a good solution for managing data regarding “adherence to” and “being on” effective treatment. Therefore, we can only hypothesize that gypsies may be less adherent to therapy, and effectively remain less on HAART, than CNGN. In previous studies, we found that gypsies attend the VACH clinics less regularly and are lost to follow-up more often, than CNGN.24,25 Gypsies are more deeply affected than CNGN by alcoholism,9,26 IVDU,9 suboptimal educational levels,9,27 and other conditions associated with lower adherence to HAART.28 Gypsies were also less likely than CNGN to remain in a naltrexone maintenance program 4 and 8 weeks after starting the program.29

The finding of worse health-related outcomes for gypsies immediately raises concerns regarding equality in access to health care. The most relevant steps in this process, that is, where differences can occur, include the time elapsed before entering medical care, the pattern of medical care use, and the type of health care setting.28 Since care for HIV-infected patients in Spain is almost exclusively provided through clinics within the National Health System, including all the VACH-associated clinics, the type of health care setting does not merit consideration as a possible source of differential access. As to the pattern of medical care use, we cannot provide accurate data. In one of the VACH centers, we found a different pattern of medical care use by gypsies,4,25 in which outpatient services are used less often, and emergency and inpatient services more frequently. In non-HIV-related settings, other authors have reported similar findings.30,31 Lastly, taking CD4-lymphocyte count as a surrogate marker of the time elapsed from HIV infection to engagement in health care, as proposed by Samet et al,32 we conclude that the delay was not longer for gypsies than for CNGN in our series, in contrast to what has been reported for ethnic, racial, and national minorities in Europe and the USA.12,33–35

Our study has several limitations. With regard to extrapolation of the results, the data are likely to be highly representative of the population of HIV-infected persons in Spain who are aware of their condition and who decided to attend a specialized clinic in the period under study. Infected individuals who ignored their condition or were reluctant to attend the clinics are likely to represent a population systematically different from the one reported. There are reasons to believe that whatever may be the factors determining unawareness or reluctance, they are probably unevenly distributed between gypsies and CNGN. Therefore, even generalizing our findings to the overall population of Spain is subject to uncertainty, which further increases in attempts to extrapolate them to different settings. Finally, the retrospective survival analysis may have been hampered by missing data and lost information and their consequent biases; attempts were made to keep these factors within predefined standards, but this limitation can still occur, as in most observational studies.

This study was funded in part by FIPSE (Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Glaxo SmithKline, Merck Sharp and Dome, and Roche Pharma, exp 000/99). A summary was presented at the XVI International AIDS Conference, held in Toronto, August 2006.