Fifty-five-year-old male without toxic habits or relevant personal history. He presents with a fever of 102°F, nausea and vomit of 24-h duration. He is initially assessed in our center ER and diagnosed with a fever syndrome without a focus; the patient is prescribed with antiemetic and antipyretic drugs and discharged from the hospital. Given the persistence of symptoms and the appearance of skin lesions, two days after his initial visit, the patient comes back to the hospital and is hospitalized in the Internal Medicine Unit.

The physical examination confirms the existence of several painful maculo-papular skin lesions of approximately 2cm in diameter, with a first location in the facial area, and spreading posteriorly toward the patient's upper limbs, chest, back, gluteal region, and lower limbs (Fig. 1). After a detailed anamnesis, the patient claims that one week prior to the symptom onset he had been manipulating the corpse of a cow with a knife that he would later use to cut food and eat it. In the light of this clinical picture, two hemocultures are drawn and the patient is referred to the Microbiology Unit.

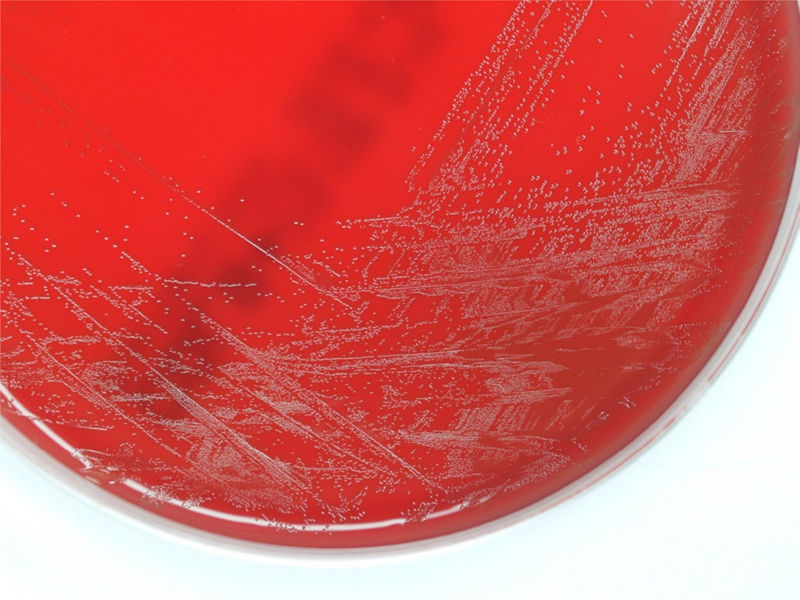

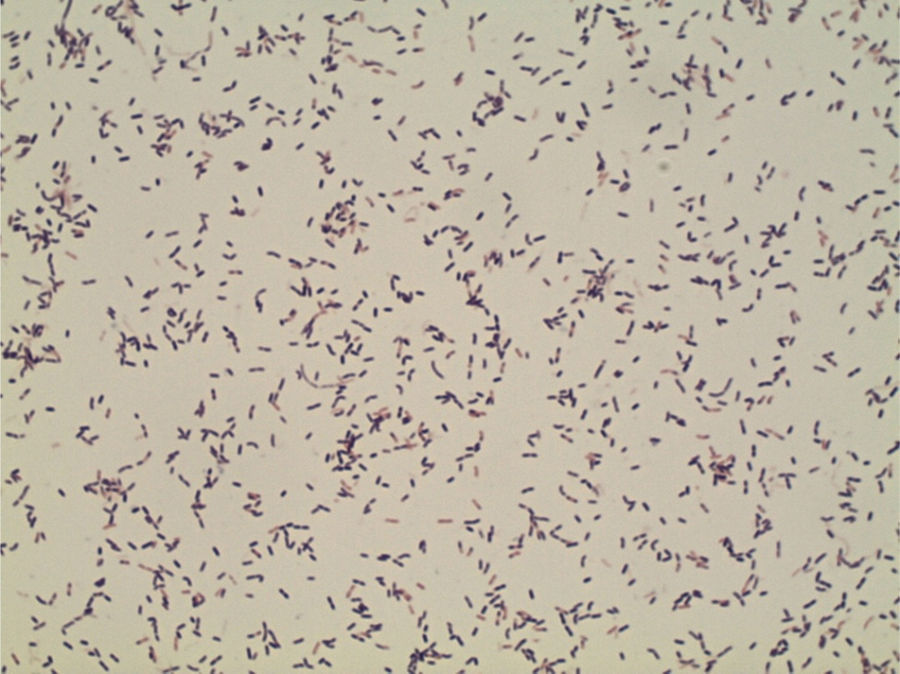

ProgressionTwenty-four hours after incubation, the BD BACTEC™ 9240 system detects growth both inside the aerobic and anaerobic hemoculture bottles. One direct Gram staining of the sample reveals pleomorphic gram-positive bacilli. Later, the subcultures drawn on blood agar and chocolate agar in a 5 per cent CO2 atmosphere confirm growth of catalase-negative alpha-hemolytic smooth colonies (Fig. 2). The Gram staining of the colonies shows short, unevenly stained, non-spore forming gram-positive bacilli (Fig. 3).

The identification is done through mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF Vitek® MS) that confirms the presence of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, and additional biochemical tests such as API® Coryne (Biomèrieux) (4020140 profile). Additionally, classical methods such as the production of SH2 on Triple Sugar Iron (TSI) agar medium reveals the typical “brush”1 shape (Fig. 4).

The strain sensitivity is determined using Etest® on Mueller-Hinton agar adding 5 per cent horse blood, and β-NAD (MHF, Oxoid) to the following antibiotics: penicillin, cefotaxim, meropenem, erythromycin, clindamycin, levofloxacin, gentamicin, and vancomycin. After applying cutting points from the CLSI M45-Ed3 document, it is confirmed that the strain responds to all the antibiotics tested except for vancomycin and gentamicin, as described in the reference.2

In this context, the patient is diagnosed with bacteremia due to E. rhusiopathiae. One transthoracic ECG and one transesophageal ECG are performed and since they are both normal, the presence of endocarditis is ruled out. After completing an 11-day therapy with a dose of penicillin G 5.000.000U, the skin lesions and the symptoms resolve and the patient is discharged from the hospital.

Final commentE. rhusiopathiae is one microorganism of wide distribution in nature and common in the animal kingdom that, occasionally, may cause infections in the human being and has three different ways of presentation: localized skin infection or erysipeloid of Rosenbach, generalized skin infection, and lastly, bacteremic infection with or without skin affectation and usually associated endocarditis.3

The E. rhusiopathiae microorganism can survive long periods of time both in the environment and in animal tissues, which is the reason why it is considered an occupational disease to which people who have a direct contact with infected animals or manipulate contaminated meat or fish (fishmongers, butchers, cooks, veterinarians, etc.) are exposed. Contagion usually happens through skin contact and, exceptionally, through the intake of contaminated products.2,3 In our case, it seems reasonable to consider the digestive way as the most likely entry site, since there was no prior skin inoculation in the patient's hand and the initial symptoms were digestive symptoms only.

For the correct identification of this bacteria it is necessary to differentiate it from bacterial genera of similar morphological or biochemical characteristics (Listeria, corynebacteria and streptococci), and gram-positive vancomycin-resistant bacteria (Lactobacillus spp., Pediococcus spp., Leuconostoc spp.).4 This is why the complete identification of all isolated gram-positive bacilli in hemocultures is essential and may reveal a greater number of bacteremic infections due to this microorganism.

With the presentation of this case, we wish to highlight the importance of systemic infection suspicion due to E. rhusiopathiae, even in immunocompetent patients,5 without any toxic habits, or a clear skin entry site.6

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interests associated with this article whatsoever.

Please cite this article as: Angulo López I, Fernández Torres M, Baldeón Conde C, Alonso Buznego L. Lesiones máculo-papulosas diseminadas en paciente en contacto con ganado. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35:603–604.