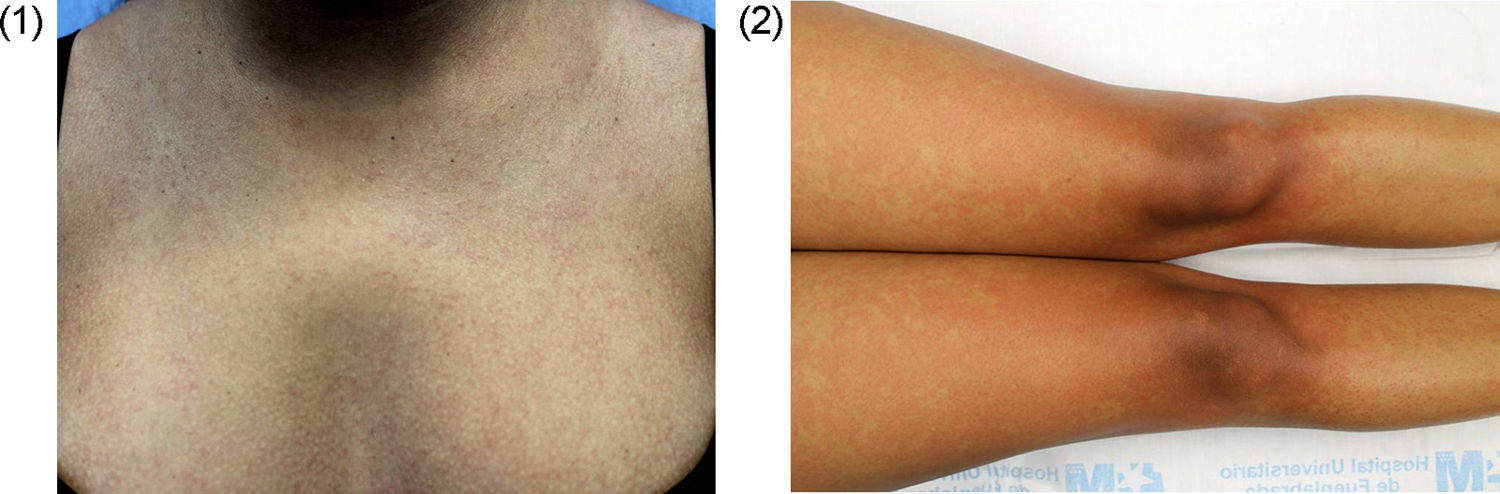

A 30-year-old woman, native of the Dominican Republic and 16 weeks pregnant, visited because of pruritic lesions that evolved over 2 days, which started in the facial area, and spread to the torso and extremities. She also had a fever of up to 38.0°C, arthralgia and conjunctival erythema that had been resolved spontaneously. She had started treatment with a vitamin complex 10 days earlier and had just returned from Santo Domingo that day. Her sister had presented similar symptoms the previous week. On examination, there were generalised macules and erythematous papules, confluent in the proximal extremities, which disappeared on performing the diascopy (Figs. 1 and 2).

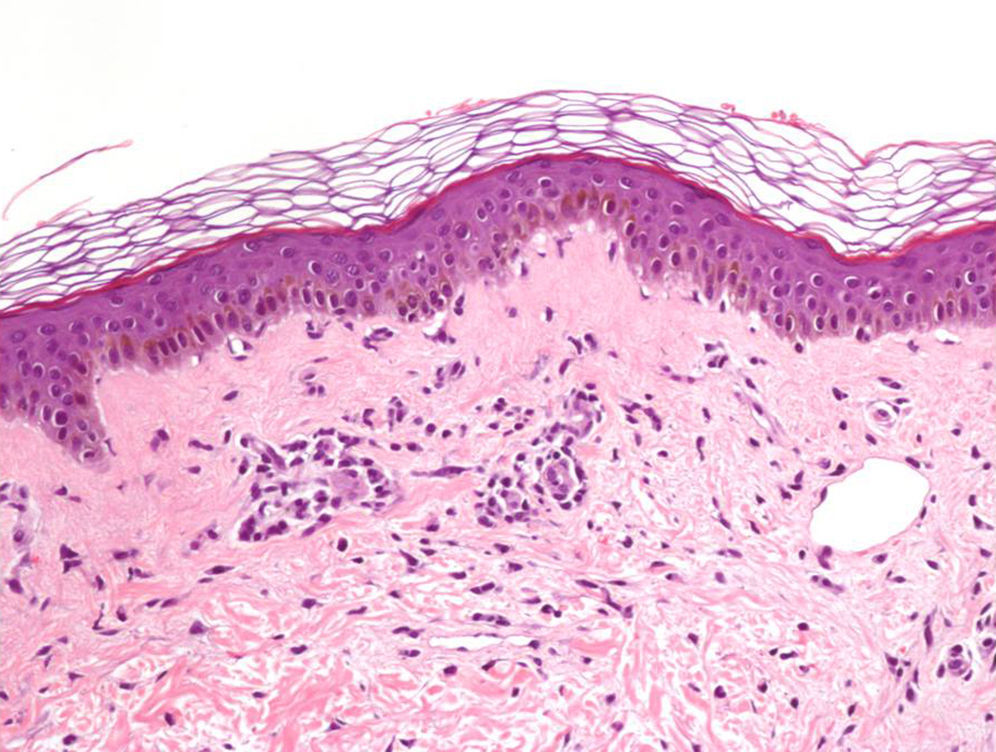

Diagnosis and evolutionWe requested basic analysis of emergencies with C-reactive protein (CRP) and Paul-Bunnell, without findings except CRP of 4.03mg/dl. We expanded serologies, with negative results for HIV, syphilis and Rickettsia, and of past infection for Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus and parvovirus B19. In light of the condition and the history that is more suggestive of chikungunya fever than dengue fever, we requested serologies of this virus, with the result of positive IgM, indeterminate IgG and negative polymerase chain reaction. A skin biopsy was performed to rule out toxicoderma, finding a mild vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer and a mild lymphohistiocytic superficial perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, compatible with viral exanthema (Fig. 3). After 10 days of treatment with dexchlorpheniramine, topical mometasone and paracetamol, the lesions had disappeared, but the arthralgias had worsened, persisting for months. The follow-up with analytical, ultrasound and foetal echocardiography in high-risk obstetric appointments did not detect any alterations and the baby was born 5 months ago, healthy. At present the patient is IgM negative and IgG positive for chikungunya virus.

CommentsThe chikungunya virus is transmitted through the bite of a mosquito of the genus Aedes, primarily Aedes aegypti, which is distributed in tropical and subtropical areas. A mutation at position 226 of the E1 envelope protein of the virus was detected in 2004, which increased the virus transmission capacity by Aedes albopictus or Asian tiger mosquito.1 Europe had received imported cases of chikungunya fever, but between 2007 and 2010 there were 2 outbreaks due to autochthonous transmission mediated by Aedes albopictus,1 which had established colonies in the Mediterranean basin.1 In 2013 another colony started in America,1 which could become an endemic zone.2 Europe will continue to receive imported cases, along with the presence of Aedes albopictus in the Mediterranean area, this provides for cases of autochthonous transmission in Spain, especially in the east and in the summer, which is the time when the vector is most active.2

Clinically, also during pregnancy,3 acute infection manifests with the triad of fever, morbilliform rash and polyarthralgias/polyarthritis. Chikungunya fever rash, unlike dengue, is not purpuric and is not accompanied by haemorrhagic complications and, in addition, arthralgias are more intense and durable. However, urticarial, vesicle-blister, vasculitic or hyperpigmentation conditions4,5 and severe manifestations such as myopicarditis or fulminant hepatitis1 have been described.

With regard to chikungunya fever during pregnancy, a comparative study of 655 uninfected pregnant women and 658 infected pregnant women found no differences after analysing birth weight, foetal mortality rate or congenital anomalies, nor in the rates of pre-term delivery, Caesarean section or gestational bleeding.3 The authors did not observe alterations in the course of pregnancy attributable to the infection.3 Another study conducted on 678 pre-term pregnant women registered 3 miscarriages, all before week 22 of gestation and newborns had no symptoms.6 However, the peripartum transmission rate reaches up to 50%1 and Caesarean section does not protect against contagion.7 40% of infants infected peripartum have neurological, cardiac or haemorrhagic complications,7 and half will develop neurological delay.8

The diagnosis is confirmed by serology in a patient with a compatible epidemiological and clinical history. The laboratory must notify all diagnosed cases. Treatment is symptomatic1 and there is no vaccine.

In conclusion, we must suspect chikungunya fever for any patient with a history of fever, polyarthralgia/polyarthritis and skin lesions. In the coming years imported cases may increase and outbreaks of autochthonous transmission in Spain may occur.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Puente-Pablo N, Khedaoui R, Freites-Martínez AD, Borbujo J. Exantema, fiebre y artralgias en una embarazada. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35:384–385.