The importance of the metabolic disorders and their impact on patients with HIV infection requires an individualized study and continuous updating. HIV patients have the same cardiovascular risk factors as the general population. The HIV infection per se increases the cardiovascular risk, and metabolic disorders caused by some antiretroviral drugs are added risk factors. For this reason, the choice of drugs with a good metabolic profile is essential.

The most common metabolic disorders of HIV infected-patients (insulin resistance, diabetes, hyperlipidemia or osteopenia), as well as other factors of cardiovascular risk, such as hypertension, should also be dealt with according to guidelines similar to the general population, as well as insisting on steps to healthier lifestyles.

The aim of this document is to provide a query tool for all professionals who treat HIV-patients and who may present or display any metabolic disorders listed in this document.

La importancia de las alteraciones metabólicas y su repercusión en los pacientes con VIH requiere un estudio particularizado y actualización continua. A los factores de riesgo presentes en población general se añaden los propios de la infección y/o del tratamiento antirretroviral que obligan a la adecuación de las pautas terapéuticas con fármacos antirretrovirales actualmente disponibles, con un mejor perfil metabólico.

Actualmente, las alteraciones metabólicas más comunes de los pacientes con el VIH (resistencia a la insulina, diabetes, hiperlipidemias u osteopenia), así como otros factores de riesgo vascular como la hipertensión arterial, deben tratarse según directrices similares a las de la población general, debiendo insistir en medidas encaminadas a estilos de vida más saludables.

El objetivo del presente documento es proporcionar una herramienta de consulta para todos los profesionales que atienden a pacientes con infección por el VIH y que pueden presentar o presentan alguna de las alteraciones metabólicas recogidas en este documento.

The importance of alterations in carbohydrate, lipid metabolism, and its impact on organ systems in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) requires specific study and continuous update.

The purpose of this document is to provide practical information from the health care perspective on the major metabolic changes that occur in HIV infection in order to offer appropriate treatment strategies to each patient and provide a reference tool for all professionals caring for patients with HIV infection who present with any of the metabolic alterations contained in this paper.1

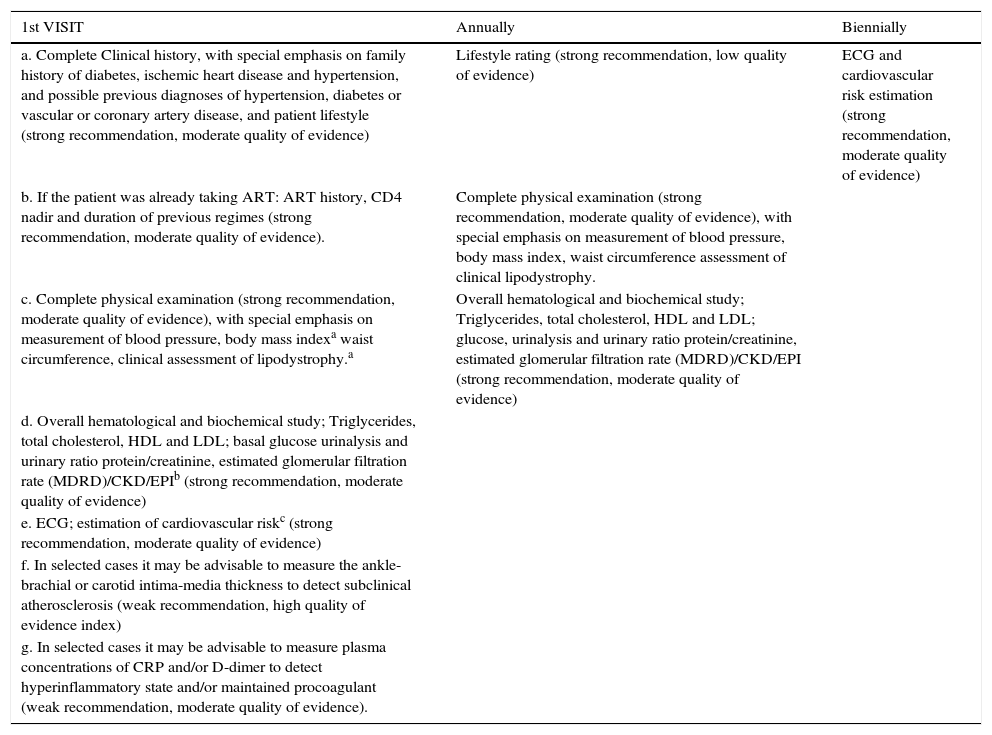

Clinical evaluationRecommendations for clinical evaluation of metabolic disorders in HIV infection are shown in Table 1.

Recommendations for clinical evaluation of a patient in terms of metabolic disorders and HIV infection.

| 1st VISIT | Annually | Biennially |

|---|---|---|

| a. Complete Clinical history, with special emphasis on family history of diabetes, ischemic heart disease and hypertension, and possible previous diagnoses of hypertension, diabetes or vascular or coronary artery disease, and patient lifestyle (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) | Lifestyle rating (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence) | ECG and cardiovascular risk estimation (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) |

| b. If the patient was already taking ART: ART history, CD4 nadir and duration of previous regimes (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence). | Complete physical examination (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence), with special emphasis on measurement of blood pressure, body mass index, waist circumference assessment of clinical lipodystrophy. | |

| c. Complete physical examination (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence), with special emphasis on measurement of blood pressure, body mass indexa waist circumference, clinical assessment of lipodystrophy.a | Overall hematological and biochemical study; Triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL and LDL; glucose, urinalysis and urinary ratio protein/creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (MDRD)/CKD/EPI (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) | |

| d. Overall hematological and biochemical study; Triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL and LDL; basal glucose urinalysis and urinary ratio protein/creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (MDRD)/CKD/EPIb (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) | ||

| e. ECG; estimation of cardiovascular riskc (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) | ||

| f. In selected cases it may be advisable to measure the ankle-brachial or carotid intima-media thickness to detect subclinical atherosclerosis (weak recommendation, high quality of evidence index) | ||

| g. In selected cases it may be advisable to measure plasma concentrations of CRP and/or D-dimer to detect hyperinflammatory state and/or maintained procoagulant (weak recommendation, moderate quality of evidence). |

In order to meet the body composition would be desirable to perform a DEXA in cases in which the same are available. If it is not possible to be performed: Body mass index, waist circumference and morphological assessment of lipodystrophy.

Overall, in all patients but especially those where it is intended to use a drug with potential nephrotoxic effect.

Following, systems that each professional or facility deemed appropriate (Framingham scales, Score or other). Hypertension (blood pressure); ART (antiretroviral therapy); ECG (electrocardiogram); HDL (high density lipoproteins); LDL (low density lipoprotein); Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD); Creatinine equation (CKD/EPI); CRP (Polymerase Chain Reaction).

It should be based on three fundamental aspects, healthy nutrition, quitting tobacco smoking and doing exercise regularly. The objectives depend on the cardiovascular risk of each individual.

Healthy nutritionThe patient with HIV infection requires nutritional support in situations of undernourishment-related weight loss, metabolic abnormalities, or body composition changes.

The practice of a healthy lifestyle in the HIV population, including regular exercise tailored to their health, abandonment of substance abuse and healthy eating habits can improve the quality of life of patients and reduce their cardiovascular risk (CVR).

Smoking cessationAccording to the American Heart Association, smoking is the greatest modifiable cardiovascular risk factor contributing to premature morbidity and mortality. We must not forget that about 60–80% of HIV+ patients smoke regularly.

Adequate therapeutic, behavioral and/or pharmacological intervention involves individual diagnosis to know the circumstances of addictive behavior, the associated stimuli, the short and long term benefits, the barriers to change and available resources, so that patients are able to secure the success of intervention.

Physical activityInterventions aimed at the progressive practice of exercise have been shown in patients with HIV, improvements in function and muscle strength, in fat redistribution and cardiovascular function (especially aerobic exercise) and lipid profile and insulin sensitivity, all of them resulting in improved CVR.

Recommendations- 1.

Modify behavioral habits for a healthy life (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence)

- 2.

Avoid or stop smoking (strong recommendation, high quality of evidence).

- 3.

Spend at least 30min on aerobic exercise daily (strong recommendation moderate quality of evidence).

There may be two important body fat abnormalities in HIV-infected patients: lipoatrophy (LA) and fat accumulation, which likely have different pathogenic mechanisms.

HIV infection contributes to the development of lipoatrophy by alteration of gene expression in adipose tissue, resulting in an increase of PGC-1a, TNFa, and α-2 microglobulin and a decline in COX-2 mRNA, COX-4, UCP2, C/EBP-a, PPAR-γ, GLUT4, LPL, leptin, and adiponectin.

Antiretroviral drugs (ARV) mainly thymidine analogs (NRTIs), protease inhibitors (PI) particularly first generation ones, and efavirenz (EFV) appear to modify adipogenesis, promote lipolysis and adipocyte apoptosis and affect decisively the secretory functions of adipose cells. In addition, some NRTIs and PI may promote insulin resistance.

The exact mechanisms that lead to visceral adiposity are largely unknown, although it has been shown that ARV exerts characteristic effects on the deposits of visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue.

Current diagnosis, except in facial assessment, is based on the objective measurement of fat with dual X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA). Other objective methods to quantify adipose tissue are ultrasonography (especially for LA Face), bioimpedance and anthropometric measurements.

Prevention is set based on therapeutic strategies including avoidance of thymidine NRTIs.

The surgical alternative should be also considered when available. In patients with facial lipoatrophy, it has an evident benefit with important psychological and social repercussion.

RecommendationsDiagnosis- 1.

The use of DEXA is recommended as a diagnostic method for the distribution of body fat (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence). If DEXA is not available, anthropometric measurements, bioelectrical impedance or ultrasound could be used instead (weak recommendation, high quality of evidence).

- 1.

Carry out a healthy lifestyle (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence).

- 2.

Avoid thymidine NRTIs (strong recommendation, high quality of evidence).

- 1.

Facial reconstructive surgery with autologous fat or synthetic substances in patients with lipoatrophy (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

- 2.

Ultrasonic liposuction is recommended only to correct cervicodorsal fat accumulation, in cases causing functional impotence (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence).

- 3.

Surgical resection in cases of localized fat deposits (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence).

Alterations in glucose metabolism are a risk factor for developing cardiovascular disease, and the risk is directly proportional to the duration of hyperglycaemia. It is recommended to measure fasting blood glucose levels at the time of HIV diagnosis, before the beginning of treatment, at 3–6 months of any antiretroviral change, and annually in patients with stable antiretroviral therapy. In case of impaired fasting glucose (≥100mg/dL) or known diabetes, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) should be measured.

Regarding the management of diabetes, lifestyle changes along with metformin therapy if needed should be the initial approach. If metformin is not enough, pioglitazone either alone or combined with metformin should be considered, but this drug should be avoided in women with osteoporosis because it may increase fracture risk. Sulfonylureas are relegated to non-obese patients with severe hyperglycaemia, because of cardiovascular concerns with some of them. Although there are no clinical studies in HIV patients to support it, the group of incretin (glucagon-like 1 (GLP-1) peptid: inhibitors of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (IDPP4) (oral) and agonists the GLP-1 receptor (AGLP-1, subcutaneous injection)) is a good alternative to sulfonylureas due to their safety so far and few interactions with antiretroviral drugs. Finally, if glucose control cannot be achieved with combinations of oral agents in type 2 diabetes or if the patient has type 1 diabetes, insulin therapy with the same pattern as the general population is recommended.

It is important to bear in mind potential drug interactions (ex. through P450) and the associated toxicity hypoglycaemic TAR in treating diabetes as with other drugs.

Recommendations- 1.

Hyperglycaemia is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and requires being treated (strong recommendation, high quality of evidence).

- 2.

Periodic screening is recommended at initiation of ART and annually over the age of 45 or below if there are associated risk factors (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

- 3.

Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) should be used for confirming diagnosis and follow-up (strong recommendation, high quality of evidence). The target is the same as for the general population (HbA1c<7%) (strong recommendation, high quality of evidence).

- 4.

ART modification should be considered in all patients with risk factors for developing DM, especially those with lipodystrophy, family history of DM or high BMI. In these patients ARVs clearly related to insulin resistance or diabetes mellitus (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence) should be avoided.

- 5.

Use similar treatment algorithm as in the general population. Metformin remains the drug of choice except in patients with severe lipoatrophy, lactacidosis risk or advanced renal disease (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence).

- 6.

If metformin is not enough to achieve glycaemic control, other drugs should be considered. Pioglitazone has its role in patients with marked insulin resistance and lipoatrophy (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence).

- 7.

Insulin is still the drug of choice when oral anti-diabetic drugs fail in type 2 diabetes, or in case of type 1 diabetes, with similar management as in the general population (strong recommendation, high quality evidence).

- 8.

Treatment of other associated cardiovascular risk factors (dyslipidaemia, hypertension) has proved to be of paramount importance for the prevention of cardiovascular events and should be considered (strong recommendation, high quality of evidence).

- 9.

Follow-up of HIV patients with abnormal carbohydrate metabolism should include HbA1c, renal function, lipid every 6 months and retinal funduscopy and microalbuminuria every year (strong recommendation, high quality of evidence), ruling out the possibility of polyneuropathy, not only due to DM, but to the virus itself, ARV, or concomitant infections.

Lipid pattern more frequently detected in HIV-infected patients is usually that of atherogenic dyslipidaemia characterized by low HDL cholesterol and increased triglyceride (TG) levels, accompanied by variable elevations of total (TC) and LDL cholesterol. This pattern is usually associated with atherogenic particles, including small dense LDL. Antiretroviral-naïve patients usually have low CT and HDL and high TG.

HIV patients should achieve LDL cholesterol levels below 100mg/dL. In case that triglycerides >00mg/dL, non-HDL cholesterol should be used as therapeutic target. Regardless of the target value of LDLc, HDL cholesterol value should be always considered in due its protective effect against the development of CVD.

StatinsThey are lipid-lowering drugs of choice for their safety, clinical effectiveness, ability to lower LDL cholesterol levels and cost.

The first choice drug should be atorvastatin due to efficacy, tolerability, experience and price, but rosuvastatin and pravastatin can also be considered. The choice of a given statin over the rest will be based on the potential for drug interactions, and the intensity of lipid disorders. Their hypolipidemic effectiveness by decreasing order is: rosuvastatin, atorvastatin and pravastatin. It is essential to evaluate potential for drug interactions due to serious reactions such as myopathy including rhabdomyolysis.

Pitavastatin is a new drug in this family has as main advantage its poor capacity to cause interactions. Only clinical interaction with lopinavir/r has been assessed, and it is not clinically relevant.

It is generally recommended to start treatment with low doses of statins and to increase the dose based on efficacy and/or toxicity.

FibratesFibrates may be considered of choice in the management of severe hypertriglyceridemia unresponsive to dietary measures or history of pancreatitis. Among them, fenofibrate (200mg/day) has a clear anti-atherogenic profile in patients with HIV.

The combination of fibrates and statins may be occasionally required, and in this case, close monitoring to detect muscular toxicities is needed.

Other drugsThere are data on the use of ezetimibe with low-dose statins in HIV-positive patients in whom the response to statins alone is poor.

ART switches to improve metabolic profileBefore initiating ART, cardiovascular risk should be assessed to choose the most appropriate treatment from a metabolic point of view. The consideration of modifying ART before using lipid-lowering agents should be analyzed in a patient-per-patient basis provided there is no risk of virologic failure and considering that the patient will be exposed to the adverse effects of the new drug. By contrast, adding a lipid lowering drug means increasing complexity of therapy and the possibility of adverse outcomes.

In general, it seems reasonable to refer the patient to the lipid specialist when LDLc goals cannot be achieved with the use of lipid-lowering drugs indicated above the maximum dose, especially when the patient's CVR is high.

Recommendations- 1.

Monitor plasma lipids in patients on ART (strong recommendation, high quality of evidence).

- 2.

Treat dyslipidaemia firstly with dietary and life style recommendations based on patient's specific lipid abnormalities (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

- 3.

HIV patients with dyslipidaemia should aim for a therapeutic LDLc target below 100mg/dL (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

- 4.

Atorvastatin should be considered as the first choice statin. Rosuvastatin and pravastatin may be alternative options. These drugs should be used for both primary and secondary prevention (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

- 5.

Fibrates are recommended as the most effective drug treatment of severe hypertriglyceridemia (>500mg/dL) refractory to dietary treatment (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

- 6.

Combination therapy with statin and fibrates is not systematically recommended because statin toxicity may be potentiated (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

- 7.

The association of ezetimibe plus statin may be useful to control dyslipidaemia in patients unable to get such a control with statins alone (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

- 8.

In patients with cardiovascular risk factors, ART should be also chosen because of its metabolic profile (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

- 9.

In patients developing metabolic abnormalities or worsening CVR, ART switch (plus lipid-lowering therapy as needed) should be considered whenever it does not compromise virological efficacy (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

There is no evidence that HIV infection per se is associated with an increased risk of hypertension (HT). Therefore, it is assumed that monitoring, clinical implications and treatment should be similar to the general population with the exception of considering avoiding risk of interactions between antiretroviral therapy and antihypertensive.

Correct blood pressure (BP) measurement should be routine practice in the care of patients with HIV infection. It is recommended to be performed at the initial HIV visit and then at least once a year whenever values are normal (SBP<130mmHg and SBP<85mmHg) and more frequently if they are above upper normal limit (SBP 130–139mmHg or DBP 85–89mmHg) or if other cardiovascular risk factors are present. The decision to start treatment is based on BP values and CVR. All patients with grade 2 or 3 hypertension are candidates for therapeutic intervention. Scientific evidence supports the goals of reducing BP values below 140/90mmHg but there is no evidence supporting larger reductions to achieve better goals.

The decision on which specific antihypertensive drug to use should take into account potential drug interactions or toxic effects that limit their use. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are the best tolerated antihypertensive drugs and the least risky for interactions with antiretroviral drugs (see http://www.hiv-druginteractions.org/). Thiazide diuretics and amlodipine in general are also safe and can be used in certain clinical situations, if the above mentioned drugs ACEI or ARB cannot be used or if combined treatment of hypertension is necessary.

Recommendations- 1.

Recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of hypertension in patients with HIV infection should be the same as those of the general population. Diet and lifestyle changes should be first considered and if necessary, antihypertensive treatment, in order to reduce cardiovascular risk, morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease (strong recommendation, high quality of evidence).

- 2.

On selecting antihypertensive drugs in patients with ARV is recommended to consider potential drug interactions and adverse effects. ACE inhibitors and ARBs combine both the best tolerably and the lowest risk of interactions (strong recommendation, high quality of evidence).

Patients with HIV infection have a higher risk of CVD than the general population. Although the mechanism of vascular injury are not well known, different factors are involved including traditional cardiovascular risk factors, ART and HIV-related parameters such as inflammation and immunodeficiency even in patients with good immunovirological control. It is plausible that the immunological and inflammatory consequences of chronic HIV infection may promote development of premature atherosclerosis and accelerated aging.

The antiretroviral drugs currently recommended in first-line regimens have limited impact in terms of metabolic and cardiovascular parameters.

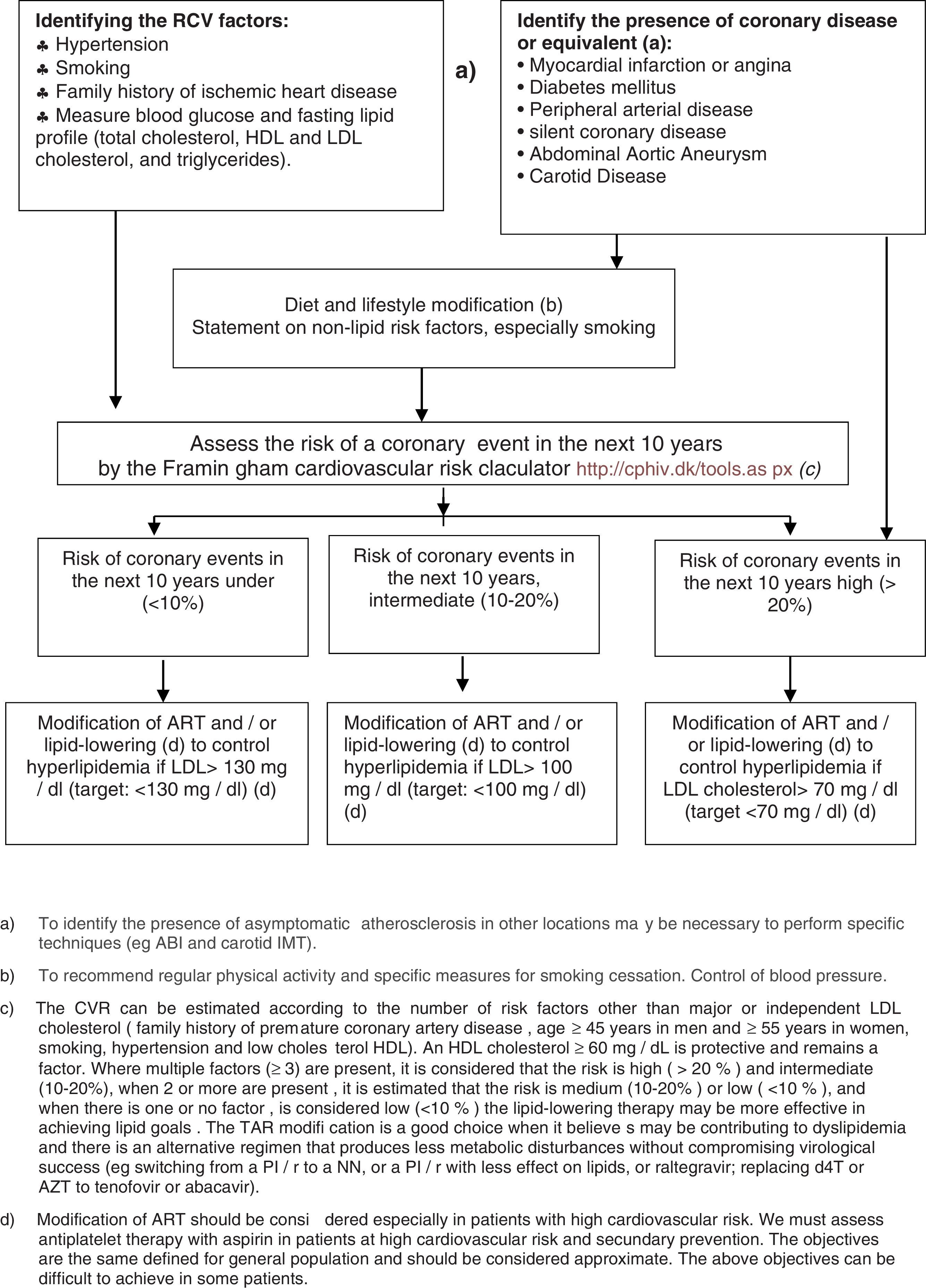

Identifying patients at high risk of CVD is essential for establishing preventive measures and CV risk assessment should be routinely included in the clinical evaluation of patients with HIV infection, especially those receiving ART (Fig. 1).

Evaluation of CVR in HIV-patients and recommendations for the prevention of cardiovascular events. (a) To identify the presence of asymptomatic atherosclerosis in other locations may be necessary to perform specific techniques (e.g. ABI and carotid IMT). (b) To recommend regular physical activity and specific measures for smoking cessation. Control of blood pressure. (c) The CVR can be estimated according to the number of risk factors other than major or independent LDL cholesterol (family history of premature coronary artery disease, age ≥45 years in men and ≥55 years in women, smoking, hypertension and low cholesterol HDL). An HDL cholesterol ≥60mg/dL is protective and remains a factor. Where multiple factors (≥3) are present, it is considered that the risk is high (>20%) and intermediate (10–20%), when 2 or more are present, it is estimated that the risk is medium (10–20%) or low (<10%), and when there is one or no factor, is considered low (<10%) the lipid-lowering therapy may be more effective in achieving lipid goals. The TAR modification is a good choice when it believes may be contributing to dyslipidemia and there is an alternative regimen that produces less metabolic disturbances without compromising virological success (e.g. switching from a PI/r to a NN, or a PI/r with less effect on lipids, or raltegravir; replacing d4T or AZT to tenofovir or abacavir). (d) Modification of ART should be considered especially in patients with high cardiovascular risk. We must assess antiplatelet therapy with aspirin in patients at high cardiovascular risk and secundary prevention. The objectives are the same defined for general population and should be considered approximate. The above objectives can be difficult to achieve in some patients.

- 1.

Individual risk of suffering a cardiovascular event should be estimated as accurately as possible (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence).

- 2.

Diet and lifestyle changes should be considered as well as the modification of all potentially modifiable factors, especially smoking risk (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

- 3.

Referral to cardiologist should be done in patients with a history of CVD and should be considered in those with high CVR (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence).

Erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, and impaired ejaculation and orgasm have been described in men. Decreased sexual desire and less satisfaction in sex have been reported in women.

Sexual dysfunction (SD) assessment should include plasma lipids and testosterone and estradiol, preferably determination of free/total testosterone ratio, as HIV seropositive patients may have increased levels of sex-binding globulin. If hypogonadism is detected, gonadotropins and prolactin should be also determined. In patients without evidence of hypogonadism, referral to specialist should be considered.

In men, detection of hypogonadism must lead to considering testosterone replacement therapy. If erection problems exist, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (sildenafil, vardenafil and tadalafil) can be prescribed. It should be taken into account that these drugs may interact with PIs, and lower doses of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors should be initially used. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors inhibitors are contraindicated in patients taking nitrates because they can enhance their hypotensive effects.

In women, topic estrogen improves dyspareunia but the role of systemic estrogen or testosterone is unclear.

If there is no obvious cause for sexual dysfunction after initial assessment or if treatment is ineffective, patients should be referred to the specialist.

Recommendations- 1.

SD assessment should be part of HIV patients because of its high prevalence and its consequences (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence).

- 2.

Use of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors should always take into consideration potential for interactions with antiretroviral drugs, especially with PIs (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

Hormonal changes may be caused by direct effect of HIV on the endocrine organs, systemic effect mediated by cytokines, opportunistic infections and HIV-associated malignancies, ARVs, or drug use. Assessment should be individualized and guided by the presence of symptoms. Symptoms are often nonspecific and common to HIV infection itself or related diseases, and a high level of suspicion is required for diagnosis.

Routine measurement of hormones is not recommended, except where there is a clinical indication by hypo or hyperfunction as in the general population. Treatment recommendations in HIV seropositive patients are similar to those of the general population.

Recommendations- 1.

Recommendations for treatment of hormonal changes in HIV patients are limited and should follow those ones used in the general population (strong recommendation, very low level of evidence).

HIV infection and ARVs may promote side effects similar to those observed in the metabolic syndrome, including hepatic steatosis. Its prevalence in HIV positive patients is 30–50%.

Insulin resistance is a key pathogenic factor. Steatosis per se does not usually cause symptoms. Laboratory diagnosis usually shows elevated transaminases below five times normal upper limits with GPT>GOT, and elevated GGT and alkaline phosphatase; hypertriglyceridemia is not uncommon. Ultrasound is the confirmatory method of choice, and it informs on whether there are other liver or extrahepatic problems. Magnetic resonance, computed tomography or elastography are also useful.

The prognosis is usually benign. As in the general population is important to distinguish hepatic steatosis from steatohepatitis, which occurs in patients with visceral obesity and insulin resistance, as well as other clinical and biological manifestations found in the metabolic syndrome. These patients have a significant risk of progression of liver damage and development of cirrhosis.

Treatment includes diet and lifestyle modification. In patients with diabetes or dyslipidaemia or chronic hepatitis virus infection, specific therapies for these conditions should be prescribed. If previously mentioned treatment is not effective enough, vitamin E for 1–2 months could be considered treatment although available data are limited.

Recommendations- 1.

In patients with diabetes or metabolic syndrome and elevated transaminases without defined etiology, hepatic steatosis should be ruled out (strong recommendation, low level of evidence).

- 2.

In patients with risk factors for the progression of hepatic steatosis, early detection and treatment to prevent the progression of liver damage should be done (strong recommendation, low level of evidence).

- 3.

At least one imaging method is recommended for diagnostic confirmation (strong recommendation, moderate level of evidence).

- 4.

Treatment should be addressed to change unhealthy diet and lifestyle habits and adequately treat existing diabetes or dyslipidaemia (strong recommendation, moderate level of evidence).

The preparation of this document has been financed with the funds from the SPNS (Spanish National AIDS Plan Secretariat).

Conflicts of interestsIn order to avoid and/or minimize any conflicts of interests, the individuals who make up this Expert Group have made a formal declaration of interests. In this declaration, some of the authors have received funding to take part in conferences and to conduct research, as well as having received payments as speakers for public institutions and pharmaceutical companies. These activities do not affect the clarity of the present document as the fees and/or grants received do enter into the recommended conflict of interests. It must be pointed out, as regards the drugs in this document, that it only mentions the active ingredient and not the commercial brand.

The SPNS (Spanish National AIDS Plan Secretariat) and the Board of Directors of GEAM (Study Group on AIDS metabolic disorders) and GeSIDA (AIDS Study Group) Directorates are grateful for the support and opinions of Adrián Curran and Juan Emilio Losa, that have contributed to improve the writing and enrich the contents of the document.

Writing Committee: Rosa Polo Rodríguez, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Secretary of the National AIDS Plan, Madrid. María José Galindo Puerto, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valencia. Carlos Dueñas, Specialist in Internal Medicine Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital Universitario, Burgos. Carmen Gómez Candela, Specialist in Endocrinology and Nutrition, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid. Vicente Estrada, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital Clínico Universitario San Carlos, Madrid. Noemí GP Villar, Specialist in Endocrinology and Nutrition, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid. Jaime Locutura, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital Universitario, Burgos. Ana Mariño, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital Arquitecto Marcide, Ferrol. Javier Pascua, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Complejo Hospitalario de Cáceres. Rosario Palacios, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga. Miguel Ángel Von Wichmman, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital Donostia, San Sebastian. Julia Álvarez, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá Henares, Madrid. Victor Asensi, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo. José Lopez Aldeguer, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital La Fe, Valencia. Fernando Lozano, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital Universitario de Valme, Sevilla. Eugenia Negredo, Fundació Lluita contra la Sida(Lluita Foundation against AIDS), Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Barcelona. Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona. Enrique Ortega, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital Universitario Valencia. Enric Pedrol, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital de Figueres, Gerona. Félix Gutiérrez, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital General Universitario, Elche. Jesús Sanz Sanz, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital Universitario de La Princesa, Madrid. Esteban Martínez Chamorro, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital Universitario Clinic, Barcelona.

All members of the Panel are authors of this publication. Writing Committee is presented in Appendix A.