Interferon-gamma release assays are widely used for the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection in Spain. However, there is no consensus on their application in specific clinical scenarios. To develop a guideline for their use, a panel of experts comprising specialists in infectious diseases, respiratory diseases, microbiology, pediatrics and preventive medicine, together with a methodologist, conducted a systematic literature search, summarized the findings, rated the quality of the evidence, and formulated recommendations following the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations of Assessment Development and Evaluations) methodology. This document provides evidence-based guidance on the use of interferon-gamma release assays for the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection in patients at the risk of tuberculosis or suspected of having active disease. The guidelines will be applicable to specialist and primary care, and public health.

Las técnicas de detección in vitro de interferón-gamma (IGRA, del inglés interferon-gamma release assays), están ampliamente implantadas para el diagnóstico de infección tuberculosa en España. Sin embargo, no hay consenso sobre su aplicación en diferentes escenarios clínicos. Para desarrollar una guía de práctica clínica sobre su uso, un grupo de trabajo compuesto por especialistas en enfermedades infecciosas, neumología, microbiología, pediatría y medicina preventiva, junto con un metodólogo, llevaron a cabo una búsqueda sistemática de la literatura, sintetizaron la evidencia y gradaron su calidad, y formularon las recomendaciones siguiendo el método GRADE (Grading of Recommendations of Assessment Development and Evaluations). Este documento proporciona una guía basada en la evidencia para el uso de los IGRA para el diagnóstico de infección tuberculosa en pacientes en riesgo de tuberculosis o con sospecha de enfermedad activa. Esta guía es aplicable en la atención especializada y primaria, y salud pública.

The diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB) infection relied solely on the tuberculin skin test (TST) until a decade ago when in vitro immunodiagnostic tests, known as interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs), became available.

The TST, the reference method for the screening of people at risk, consists of the intradermal injection of PPD-S (Seibert's purified protein derivative), or the PPD-RT23 equivalent in Spain. The PPD contains a mixture of more than 200 antigens that are shared by mycobacteria other than Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and includes the vaccine strain of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) and most non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM). Therefore, people sensitized by previous exposure to NTM or the BCG vaccine may respond to a TST. Another major limitation is the loss of sensitivity of the test in certain groups, such as immunosuppressed patients and young children. It should also be remembered that a negative TST obtained early after the onset of infection with M. tuberculosis does not exclude infection because the test takes up to eight weeks to emerge as positive. This interval is usually referred to as the “window period.”

The IGRA tests are based on the in vitro quantification of the cellular immune response. IGRAs detect interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) release by sensitized T cells after stimulation with specific M. tuberculosis antigens. The two main antigens used are the 6-kD M. tuberculosis early-secreted antigenic target protein (ESAT-6) and the 10-kD culture filtrate protein (CFP-10), encoded in the region of difference 1 (RD1), which is present in M. tuberculosis but not in BCG nor in most NTM. This new technology was rapidly adapted from initial in-house methods to the two commercially available assays: the QuantiFERON®-TB Gold assay (QFT-G) (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and the T-SPOT®.TB assay (Oxford Immunotec, Oxford, UK). Like the TSTs, IGRAs have a window period of conversion after exposure to M. tuberculosis, but the duration of this window has not been clearly determined.

Scope and objectivesCurrently there is no consensus on the use of IGRAs in different clinical scenarios and settings. Despite the abundance of literature about IGRAs, there is a scarcity of good quality evidence evaluating important patient outcomes in given populations. This, in turn, is reflected in the inconsistency of the recommendations of official organizations and scientific societies, which largely rely on expert opinion (6, 7). Moreover, recommendations that are suitable for one area or country may not be appropriate for another. To this end, two consensus documents were produced in 2008 and 2010 on the diagnosis and treatment of TB in adults (8) and children (9), respectively, on the use of IGRAs in Spain. Therefore, there was a need for updated recommendations, based on the best available evidence and formulated according to the modern methodology for the elaboration of guidelines.

The current document provides evidence-based guidance to the specialist and primary health-care providers and public health authorities on the use of IGRAs for diagnosing TB infection in both immunocompetent and immunosuppressed adults and children of any age at risk for or suspected of having active TB. The final objective of the document is to minimize the uncertainty and variability in the diagnosis of TB infection by the IGRAs. It is beyond the scope of these guidelines to give advice on when the screening of TB infection should be performed or when and how they should be treated. The authors refer the readers to other guidelines that provided specific guidance on that (10).

A full version of the document can be found online.1

MethodologyA panel of experts comprising specialists in infectious diseases, respiratory diseases, microbiology, pediatrics and preventive medicine, and a methodologist conducted a systematic review and formulated specific recommendations following the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations of Assessment Development and Evaluations) methodology.

Clinical questions and outcomesClinical questions were formulated according to the PICO structure (population, intervention [index test], comparison [reference test] and outcomes), with the outcomes of interest prioritized. The panel established the following outcomes, hierarchically classified according to their clinical relevance (from highest to lowest):

- 1.

The efficacy of chemoprophylaxis based on the IGRA results.

- 2.

The predictive values of the IGRAs for the development of active TB based on the IGRA results.

- 3.

The correlation between rate of exposure and risk factors for TB infection.

- 4.

The sensitivity and specificity of IGRAs for the diagnosis of active TB.

Search strategies were designed to identify systematic reviews of diagnostic studies and relevant individual studies that updated existing systematic reviews. The search was conducted in the following electronic databases, without language or temporal limitations, up to March 2013: MEDLINE (accessed through PubMed) and EMBASE (accessed through Ovid). The panel was kept updated of new literature until June 2015, to ensure the inclusion of relevant studies published while the guidelines were being developed. Publications on resource use and costs were identified by searching in the NHS EED database up to October 2014.

Quality of the evidence and recommendationsThe quality of the evidence was assessed according to the GRADE international working group. The panel assessed the quality of the evidence for the following outcomes: First, methodological adequacy; second, consistency between the results of the different studies; third, availability of direct evidence; fourth, precision of the estimators of effect, and fifth, publication bias. After the evaluation process, the quality of evidence was classified into four categories for each outcome: high, moderate, low, and very low.

The panel formulated the recommendations with the evidence available for each clinical question according to the GRADE methodology. For the direction (against/for an intervention) and the strength (strong/weak) of a recommendation, the panel weighed the overall quality of the evidence, the balance between benefits and harms, the relative importance of the outcomes, and the resource use and costs. When formulating the recommendations, studies reporting data from high-income, low-prevalence countries were prioritized whenever available. When there were no data from these settings, studies from intermediate- or high-prevalence countries were also included.

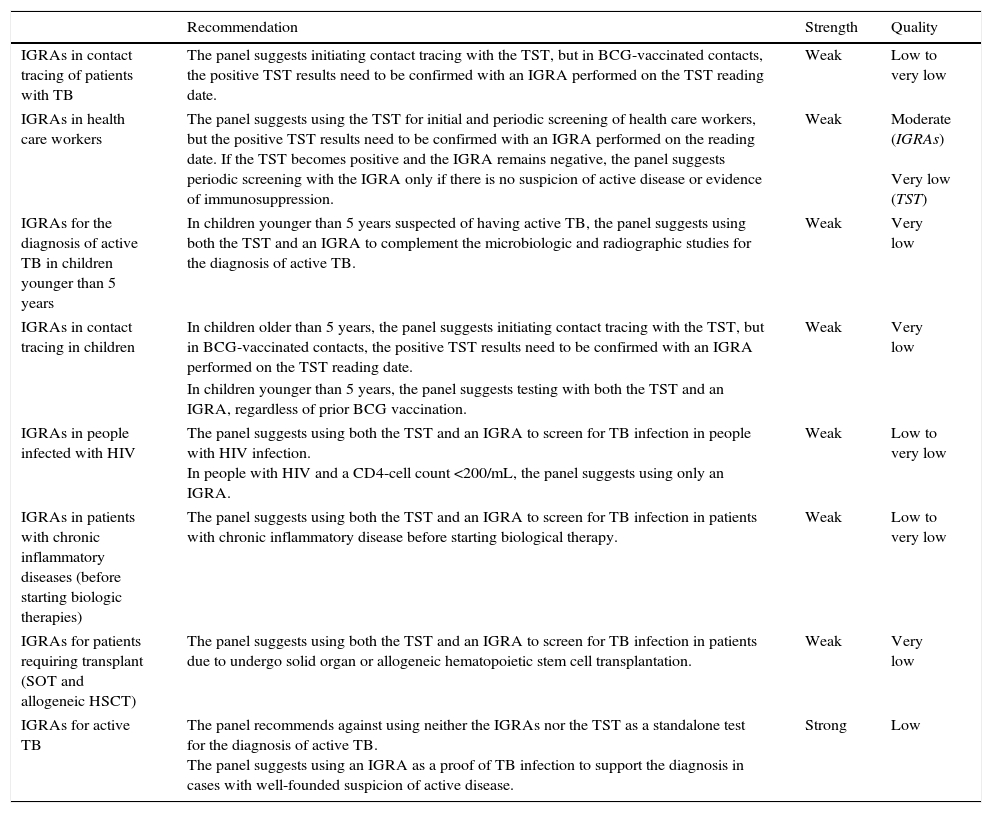

RecommendationsA summary of the recommendations and synthesis and quality of the evidence used is provided in Table 1.

Summary of the recommendations for different clinical settings.

| Recommendation | Strength | Quality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IGRAs in contact tracing of patients with TB | The panel suggests initiating contact tracing with the TST, but in BCG-vaccinated contacts, the positive TST results need to be confirmed with an IGRA performed on the TST reading date. | Weak | Low to very low |

| IGRAs in health care workers | The panel suggests using the TST for initial and periodic screening of health care workers, but the positive TST results need to be confirmed with an IGRA performed on the reading date. If the TST becomes positive and the IGRA remains negative, the panel suggests periodic screening with the IGRA only if there is no suspicion of active disease or evidence of immunosuppression. | Weak | Moderate (IGRAs) Very low (TST) |

| IGRAs for the diagnosis of active TB in children younger than 5 years | In children younger than 5 years suspected of having active TB, the panel suggests using both the TST and an IGRA to complement the microbiologic and radiographic studies for the diagnosis of active TB. | Weak | Very low |

| IGRAs in contact tracing in children | In children older than 5 years, the panel suggests initiating contact tracing with the TST, but in BCG-vaccinated contacts, the positive TST results need to be confirmed with an IGRA performed on the TST reading date. | Weak | Very low |

| In children younger than 5 years, the panel suggests testing with both the TST and an IGRA, regardless of prior BCG vaccination. | |||

| IGRAs in people infected with HIV | The panel suggests using both the TST and an IGRA to screen for TB infection in people with HIV infection. In people with HIV and a CD4-cell count <200/mL, the panel suggests using only an IGRA. | Weak | Low to very low |

| IGRAs in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases (before starting biologic therapies) | The panel suggests using both the TST and an IGRA to screen for TB infection in patients with chronic inflammatory disease before starting biological therapy. | Weak | Low to very low |

| IGRAs for patients requiring transplant (SOT and allogeneic HSCT) | The panel suggests using both the TST and an IGRA to screen for TB infection in patients due to undergo solid organ or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. | Weak | Very low |

| IGRAs for active TB | The panel recommends against using neither the IGRAs nor the TST as a standalone test for the diagnosis of active TB. The panel suggests using an IGRA as a proof of TB infection to support the diagnosis in cases with well-founded suspicion of active disease. | Strong | Low |

TB, tuberculosis; TST, tuberculin skin test; BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guerin; IGRAs, interferon-gamma release assays; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SOT, solid organ transplantation; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Recommendation: The panel of experts suggests as recommendations initiating contact tracing with the TST, but in BCG-vaccinated contacts, the positive TST results need to be confirmed with an IGRA performed on the TST reading date. (Weak recommendation; low to very low quality of evidence.)

Use of IGRAs to screen for TB infection in health care workersRecommendation: The panel of experts suggests as recommendations using the TST for initial and periodic screening of health care workers, but the positive TST results need to be confirmed with an IGRA performed on the reading date. (Weak recommendation; moderate and very low quality of evidence for IGRAs and TST, respectively.)

If the TST becomes positive and the IGRA remains negative, the panel suggests periodic screening with IGRAs only if there is no suspicion of active disease or evidence of immunosuppression. (Weak recommendation; very low quality of evidence.)

Use of IGRAs for the diagnosis of active TB in children younger than 5 yearsRecommendation: In children younger than 5 years suspected of having active TB, the panel suggests using both the TST and an IGRA to complement the microbiologic and radiographic studies for the diagnosis of active TB. (Weak recommendation; very low quality of evidence.)

Use of IGRAs for contact tracing in childrenRecommendation: In children older than 5 years, the panel suggests initiating contact tracing with the TST, but in BCG-vaccinated contacts, the positive TST results need to be confirmed with an IGRA performed on the TST reading date. (Weak recommendation; very low quality of evidence.)

In children younger than 5 years, the panel suggests testing with both the TST and an IGRA, regardless of prior BCG vaccination. (Weak recommendation; low quality of evidence.)

Use of IGRAs when screening for TB infection in people infected with HIVRecommendation. The panel of experts suggests as recommendations using both the TST and an IGRA to screen for TB infection in people with HIV infection. (Weak recommendation; low quality of evidence.)

In people with HIV and a CD4-cell count <200/mL, the panel suggests using only an IGRA. (Weak recommendation; very low quality of evidence.)

Use of IGRAs to screen for TB infection in patients with chronic inflammatory disease before treatment with biologic therapiesRecommendation: The panel of experts suggests as recommendations using both the TST and an IGRA to screen for TB infection in patients with chronic inflammatory disease before starting biological therapy. (Weak recommendation; low to very low quality of evidence.)

Use of IGRAs to screen for TB infection before transplantationRecommendation: The panel of experts suggests as recommendations using both the TST and an IGRA to screen for TB infection in patients due to undergo solid organ or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). (Weak recommendation; very low quality of evidence.)

Use of IGRAs for the diagnosis of active TBRecommendation: The panel of experts suggests as recommendations against using the IGRAs or TST as a standalone tests for the diagnosis of active TB. (Strong recommendation; low quality of evidence.)

The panel suggests using an IGRA as a proof of TB infection to support the diagnosis in cases with well-founded suspicion of active disease. (Weak recommendation; low quality of evidence.)

Further considerationsThe panel noted the following additional considerations:

- 1.

The resources needed for IGRAs to be implemented are low. However, implementation in non-urban settings, where a close laboratory for rapid handling of samples is required, may be difficult. This was acknowledged to be particularly important when using the T-SPOT.TB, which should be performed within the first 24h, or in the case of the T-SPOT.TB® Extend, within 48h after incubation. Furthermore, the need for venous punctures in large collectives and requirement of a reference laboratory to handle sample batches, could make the use of IGRAs difficult for contact tracing at a community level.

- 2.

Although there was no attempt to distinguish between the two IGRAs in the final guidelines, some panel members favored the use of the T-SPOT.TB in HIV-infected (CD4 <200) and children, based on the perception of higher sensitivity over the QTF-GIT. However, it was acknowledged that the available evidence showed no clear difference between the two tests.

- 3.

An emphasis was placed on the importance of screening before any underlying disease becomes too advanced, because this can compromise the yield of IGRAs. This was particularly relevant for patients with HIV and for candidates for transplantation or biologic therapies. Likewise, performing the QTF-GIT when leucopenia is present (particularly in HSCT) should be avoided because it increases the likelihood of indeterminate results.

- 4.

There was no specific recommendation on whether the TST and an IGRA should be performed simultaneously or sequentially (start with TST and follow with an IGRA in case of negativity) when both tests are recommended. The panel considers that the choice of strategy should be guided by the circumstances of a given patient and the singularities of each center.

- 5.

Regarding the use of IGRAs in the diagnostic work-up of TB, the panel emphasizes:

- •

Ensure rational use of IGRAs by using them only when there is a well-founded clinical suspicion.

- •

A positive IGRA in patients with compatible symptoms, particularly in immunosuppressed patients and children, must prompt active investigation for active TB.

- •

It remains important to establish a diagnosis of TB by conventional microbiologic and/or molecular methods.

- •

- 6.

If a baseline test is negative (IGRAs or the TST) in HIV-infected patients with very low CD4 cell counts, it should be repeated once immunity has improved with antiretroviral therapy. This approach may be useful to detect additional positive cases.

- 7.

In general, an IGRA is preferred when testing those who are unlikely to return for TST reading, such as patients with alcoholism, drug abuse disorders, and the homeless. In these groups, the use of IGRAs may increase test completion rates.

- 8.

Finally, the panel emphasizes the need for health care workers to adhere to TB prevention protocols in place.

The panel considers that these guidelines should be updated within five years of their publication, or earlier if relevant information becomes available.

Conflict of interestAll the authors provided a conflict of interest statement. M.S. declared the following conflicts of interest: he received a fee for speaking at two conferences sponsored by Inverness Medical Iberica, S.A.U., supplier of the QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-tube in Spain, and he is the PI of a Clinical Trial assessing QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-tube in contact-tracing, which was supplied with blood collection tubes by Cellestis, Inc. (Carnegie, Australia). Any declared conflicts of interest were not deemed relevant to preclude involvement in the deliberations of the panel.

Funding and editorial independenceThe panel received no funding from any for-profit companies or organizations. The Spanish Society of Respiratory Diseases and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) hosted the in-person meetings, while SEPAR and the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC) funded the travel and housing costs for members to attend the meetings. Neither the SEIMC nor SEPAR have direct or indirect influence on the elaboration of the guidelines.

The authors extend their sincere gratitude for the following External Reviewers: Fernando Alcaide (Service of Microbiology, Bellvitge University Hospital, University of Barcelona, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona), Ángel Domínguez (Service of Infectious Diseases, Hospital Virgen Macarena, Sevilla), Jordi Dorca (Service of Pneumology, Bellvitge University Hospital, University of Barcelona, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona), María J. Mellado Peña (Service of General Pediatrics and Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Hospital Universitario Infantil La Paz, Madrid), Juan J. Palacios (Regional Laboratory for Mycobacteria, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias), Antonio Rivero (Service of Infectious Diseases, Hospital Reina Sofía, Córdoba), Anna Rodés (Program of Prevention and Control of Tuberculosis, Public Health Agency of Catalonia), Juan Ruíz Manzano (Service of Pneumology, Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona, Barcelona).

The working group thanks SEPAR for providing the venue and infrastructure for the panel's meetings.