Scrub typhus (ST) is an arthropod-borne disease caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi. It is endemic throughout the “tsutsugamushi triangle”, which stretches from northern Japan to northern Australia, and to Pakistan and Afghanistan.1 However, autochthonous cases of Chile suggest the existence of an endemic focus in South America.2

Due to the increase in international travellers, multiple imported cases have been reported in non-endemic regions. In Europe, Costa et al.3 collected 40 patients since 1986. However, to our knowledge, no scrub typhus cases from travellers returning to Spain have been published. Herein, we report a PCR-confirmed-case of a patient diagnosed of ST.

In November 2021, a 51-year-old Chinese male attended the Emergency Department of Hospital 12 de Octubre (Madrid, Spain) suffering four-days-fever up to 39°C and retroocular headache. The patient had no remarkable medical records and he had returned 3 days before, from a one-month trip in a rural area of Haian (in Jiangsu, 200km from Shanghai) where he had been working in rice fields.

Laboratory tests revealed increased transaminases, especially cholestatic enzymes, and C-reactive protein. A chest X-ray showed mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Abdominal ultrasound showed slight thickening of the gallbladder. Antibiotic therapy was initiated under suspicion of acute cholangitis (Fig. 1).

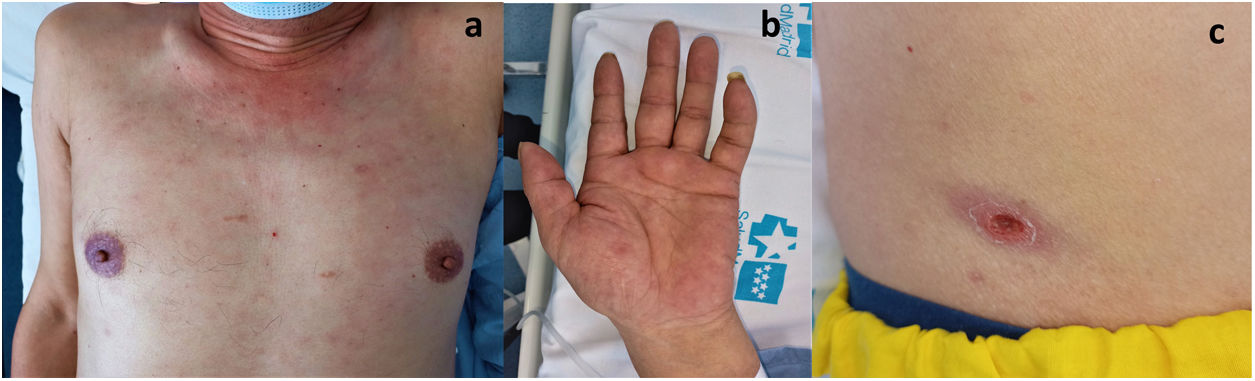

Two days later, the patient developed a maculopapular rash with palmar involvement. On physical examination, he presented a necrotic crust over a well-delimited ulcer compatible with a black eschar. Suspecting a rickettsia infection, we started empirical treatment with doxycycline.

Serology for R. conorii (the only one available in our hospital) was negative. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay targeting 56-kDa type-specific antigen gene (TSA56) from an eschar swab sample was performed at the Center of Rickettsiosis and Arthropod-Borne Diseases (Logroño, Spain). Nucleotide sequence analysis showed the presence of O. tsutsugamushi. Hence, the patient was diagnosed with ST. After treatment with doxycycline, skin lesions rapidly improved and liver enzymes normalized.

O. tsutsugamushi is transmitted to humans by the bite of larval stages of trombiculid mites.1 The infection begins at the bite-site with a papule that becomes an eschar (observed in 60–100% of patients). After 10–12 days of incubation, high fever, headache and arthromyalgias begin. The maculopapular rash affecting the trunk and limbs usually appears around the fifth day. Cutaneous manifestations are frequently the key for suspicion of this disease. Liver disorders may be found, mainly increased levels of AST and ALT, though cholangitis has been described as a possible manifestation of scrub thypus.4 Polyadenopathies are often present in these patients. Jeong et al.5 published a review about the radiological manifestations, observing gallbladder wall thickening and mediastinal lymphadenopathy in 47% and 91% of patients, respectively. In severe cases, encephalitis, cardiomyopathy, and interstitial pneumonia develop, and without proper treatment, the disease can progress to death.

Classical manifestations are not always present, Nachega et al.6 described lower frequency of rash and black eschar in travellers compared to local cases, which can be explained by differences in host immunity, geographical differences in disease epidemiology, or investigators’ clinical diagnostic skills.

Diagnosis can be made by serological studies. However, low antibody titres are common in the first 4–5 days of illness and for confirmation a posterior seroconvertion or seroreinforcement is required. In addition, the potential cross-reactions with other rickettsiae are described. PCR on eschar biopsies has demonstrated high sensitivity in the early stages of the disease and like in other diseases produced by ricketsiae that present an eschar, a swab eschar also has shown high sensitivity using molecular tools.7

The treatment of choice is doxycycline twice daily for 3–7 days and it should be started as soon as the diagnosis is suspected.6

We report the first case of imported scrub typhus in Spain to our knowledge. In the series reported by Costa et al.3 there is not a single case imported from China despite being included in the “tsutsugamushi triangle”.

Prior to the 1980s, cases of ST were observed mainly in the south of Yangtze River regions. However, over the past decade, ST prevalence has increased in several areas of China that can be divided into three distinct regions, namely North (Anhui, Jiangsu, Shandong), Southwest (Yunnan, Sichuan), and South (Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Hunan, Jiangxi, Zhejiang).8

The greater knowledge of other diseases produced by rickettsiae and initially described in other regions of Europe, Asia or Africa, such as Dermacentor-borne necrotic erythema and lymphadenopathy (R. slovaka), lymphangitis-associated rickettsiosis (R. sibirica subsp. Mongolitimonae) or African tick bite fever (R. africae),9,10 has allowed us to improve our ability to diagnosis these conditions in our country. Therefore, we consider necessary to highlight the importance of suspecting this disease in patients who come from endemic areas. Although it is something exceptional, it will be increasingly likely to find cases like this in the future, and an early diagnosis will let start an empirical treatment and avoid more serious and even fatal cases.1

Funding sourcesNone reported.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.