The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) 1951 Refugee Convention (July 28th) on the status of refugees defines a refugee as a person who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it”.1

According to the report of the UNHCR published in June 2014, it was estimated that at the end of 2013, a total of 51.2 million people were living outside their home countries because of persecution, armed conflict, violence, and systematic violation of human rights. This is the highest figure recorded since the end of the Second World War. Data from the first six months of 2014 show that, for the first time, Syria has become the main country of origin, followed by Afghanistan, Somalia, South Sudan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Myanmar, Iraq, and Colombia. The list of countries that accept the most refugees is led by Pakistan, followed by Lebanon, Iran, Turkey, Jordan, Ethiopia, Kenya, Chad, Uganda, and China,2,3 many of which have difficulty attending to the needs of their own populations.

UNHCR data for 2014 show that 866,000 people sought international protection in the 44 most industrialized countries. This is the highest figure recorded in the last 20 years. Of these 44 countries, only 5 (Germany, the United States, Turkey, Sweden, and Italy) received 60% of the requests for asylum. The European Union (28 countries) received 216,000 requests, and the Russian Federation received 168,000 requests (mainly as a result of the conflict in Ukraine). In Turkey, it is estimated that in August 2014, around 1 million people were taken in. Of these, 217,000 were living in refugee camps.4 In the year 2014 alone, it is estimated that 218,000 refugees and migrants crossed the Mediterranean. Of these, at least 3419 died.

During the year 2014 in Spain, a total of 5615 applications for international protection were received, compared with 4285 in 2013 and 2580 in 2012. The main countries of origin were Syria (1510 applicants), Ukraine (895 applicants), and Mali (595 applicants). Nevertheless, only 385 were eventually recognized as refugees in Spain in 2014.2

The crisis now being faced by Europe as a result of the distribution and settlement of refugees led the European Commission to propose a distribution strategy based on four criteria: population, GDP, level of unemployment, and the previous efforts of each country to accept refugees (weighted 40–40–10–10%). Thus, the quota assigned to Spain would be 14,931 refugees, the third highest figure in the EU after Germany (31,443 refugees) and France (24,031).5

Refugees are exposed to serious health risksEach phase of a refugee's journey (leaving the home country, the journey itself, the arrival, and an eventual return) carries health risks. Starting in their country of origin, refugees suffer the consequences of armed conflict, food shortages, poor medical attention, and the destruction of their communities. All of these factors exert a harmful effect on mental and physical health. The journey does not improve the refugee's condition owing to the many difficulties that have to be faced: lack of suitable health and hygiene, famine, overcrowding, exploitation, accidents, violence, exposure to extreme temperatures, financial ruin, and the distress associated with abandoning one's country of origin.6,7 As an example, of the 137,000 refugees who crossed the Mediterranean between January and June 2015, approximately 1850 are thought to have died or disappeared in the sea, that is, three times more than the 590 who died crossing the sea in all of 2014.8

These factors lead to increases in the frequency of infectious diseases, such as food poisoning, respiratory infections, typhoid fever, cholera, and tuberculosis as well as measles epidemics. The difficulties refugees face are made worse by poor vaccination campaigns (e.g., polio) and sexually transmitted diseases affecting women and girls as a result of abuse and rape. However, one of the major impacts of this situation is on mental health, which takes the form of post-traumatic stress disorder and other conditions, which, in the long term, can exacerbate existing mental disorders, mood disturbances, anxiety disorders, psychosis, and substance abuse.9–11

The potentially most common infections in refugeesThe crises during the last 20 years in Iraq, Somalia, Libya, Ivory Coast, Yemen, and, more recently, Syria have revealed a new phenomenon: displaced persons who originate from urban areas and who now make up more than half of all refugees. Furthermore, the sociodemographic and epidemiologic profile of these persons has changed, in that they are now older and from middle-income countries, with a lower prevalence of contagious diseases and more chronic non-infectious diseases.12,13

Immigrant and refugee health status is as much a consequence of exposure, living conditions, and access to health care in the country of origin as it is a consequence of the journey itself.14 Refugees, who by definition have been forced to abandon their country of nationality, are at increased risk of overcrowding, precarious living conditions, and violence. Mental health is a basic element in the health care of these persons.15

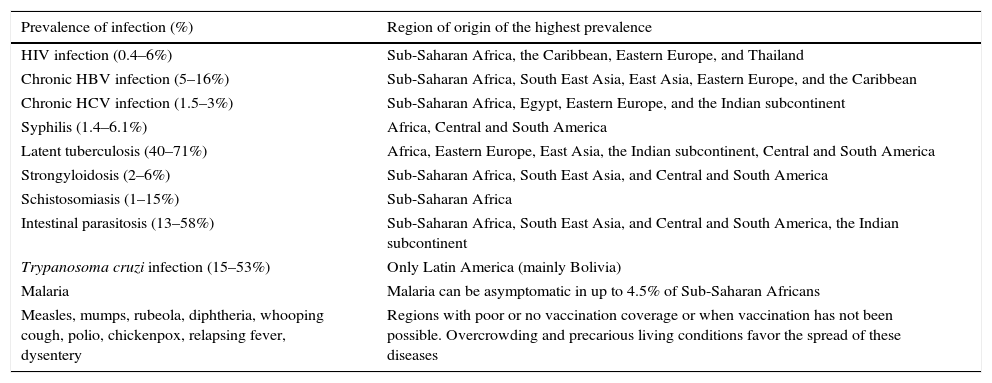

Data on the prevalence of infectious diseases among refugees are scarce, although much of the information could probably overlap with that of immigrants from the same region. Therefore, when infectious diseases are suspected among refugees, both cosmopolitan and geographically restricted infections should be borne in mind. Table 1 shows the main infections in terms of public and individual health. The frequency of the different infections depends largely on the region of origin and the living conditions found there. In addition, epidemics are often favored by overcrowding.9,14,16–22 Cases of epidemic louse-borne relapsing fever have recently been reported among Eritrean refugees.23

Most common infections suitable for screening in asymptomatic immigrants and refugees.

| Prevalence of infection (%) | Region of origin of the highest prevalence |

|---|---|

| HIV infection (0.4–6%) | Sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, Eastern Europe, and Thailand |

| Chronic HBV infection (5–16%) | Sub-Saharan Africa, South East Asia, East Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Caribbean |

| Chronic HCV infection (1.5–3%) | Sub-Saharan Africa, Egypt, Eastern Europe, and the Indian subcontinent |

| Syphilis (1.4–6.1%) | Africa, Central and South America |

| Latent tuberculosis (40–71%) | Africa, Eastern Europe, East Asia, the Indian subcontinent, Central and South America |

| Strongyloidosis (2–6%) | Sub-Saharan Africa, South East Asia, and Central and South America |

| Schistosomiasis (1–15%) | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| Intestinal parasitosis (13–58%) | Sub-Saharan Africa, South East Asia, and Central and South America, the Indian subcontinent |

| Trypanosoma cruzi infection (15–53%) | Only Latin America (mainly Bolivia) |

| Malaria | Malaria can be asymptomatic in up to 4.5% of Sub-Saharan Africans |

| Measles, mumps, rubeola, diphtheria, whooping cough, polio, chickenpox, relapsing fever, dysentery | Regions with poor or no vaccination coverage or when vaccination has not been possible. Overcrowding and precarious living conditions favor the spread of these diseases |

Medical care for refugees should take into account both the health status of the migrant and the well being of the host community. Refugees differ from other immigrant groups in that they have specific health care needs. In addition to a greater risk of diseases that are prevalent in their countries of origin (see above), refugees may have been exposed to unhealthy living conditions and subjected to violent acts and traumatic situations. Therefore, clinical care should be based on a multidisciplinary approach that covers infectious diseases, mental health, chronic conditions, and obstetric-gynecologic care.24,25

One of the main strategies for provision of medical care to refugees should be the design and application of screening protocols that can detect the more prevalent health problems early, not only in adults but also in children (infectious diseases, chronic conditions and mental health), and take into consideration the cultural and linguistic peculiarities of the population they are applied to. Such an approach should be complemented by vaccination programs for both children and adults in order to prevent epidemics, especially in vulnerable groups. Ethical considerations aside, these measures require the application of specific resources to ensure that the health of the displaced persons and the host population is not negatively affected.26,27

Screening programs for immigrants and refugees have been questioned from an ethical viewpoint, since they could be considered a limitation to these groups’ rights.28 However, it is important to highlight that a screening program is not a threat in itself, but that ethical considerations could arise with respect to the use made of the results.

The key role of qualified professionalsIn recent years, the emergence and re-emergence of infections have proven to be major health problems. More frequent travel, international trade, and migration (unavoidable in some cases and the result of extremely poor living conditions in others), play a major role in the transmission of pathogens. This problem is compounded by increasingly easy international travel and, in the case of undocumented migrants and refugees, the poor conditions of the journey to the host country and the lack of health care during the journey. Examples of recent infections include the H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009 and infections caused by Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), West Nile virus, chikungunya virus, and Ebola virus.29 In addition, it is important to remain vigilant with respect to common infections (see above), such as tuberculosis, HIV infection, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and soil-transmitted helminth infections, whose incidence can increase in developed countries with the arrival of migrants and refugees from areas with poorer health care.17,20,30 We must also be prepared against rare pathogens and infections that are no longer common in our areas but are now being detected among refugees (e.g., cutaneous diphtheria, shigellosis, and louse-borne relapsing fever).9,23,31 Finally, the emergence (or re-emergence) of exotic pathogens is yet another potential risk associated with population movements. Malaria, chikungunya virus infection, dengue fever, and Congo-Crimean hemorrhagic fever are a few examples of diseases that can be transmitted by vectors already present in Spain.29,32–34

In order to address current challenges and those that will undoubtedly appear in the future, we need professionals who are qualified and experienced in the fields of infectious diseases and clinical microbiology. This need has already been demonstrated in infections such as HIV, where the experience of the health care professionals was associated with patient survival.35 Spain has one of the highest percentages of experts in infectious diseases in Europe and is renowned internationally in this field. During the period 2000–2013, Spain occupied the fourth position worldwide in the production of manuscripts in the specialty of infectious diseases and the sixth position for manuscripts in the field of clinical microbiology.36 It is therefore difficult to understand how the field of infectious diseases has not been officially recognized as a medical specialty in its own right. The Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology has spent 20 years requesting the creation of a specialty in infectious diseases,37 yet no system has been created to ensure that training in infectious diseases and the physicians working in this area benefit from legal recognition. In most neighboring countries, the specialty of infectious diseases is fully recognized.38 Royal Decree 639/2014 (dated 25th July)39 does nothing to improve this situation, since it excludes infectious diseases as a new specialty and relegates microbiology to a branch of laboratory work with a training program that is insufficient to cover present and future needs.

It is paradoxical that a group of professionals who have never failed to step up to the challenges presented by infectious diseases (AIDS epidemic, emergence of multiresistant pathogens, rational use of antimicrobial drugs, infections in transplant recipients, and severe emergencies such as Ebola virus disease) receive almost no recognition from the health authorities. Moreover, the education and training possibilities proposed in the Royal Decree are patently insufficient according to the recommendations of the European Union in Directive 2005/36/EC and the European Union of Medical Specialists in the section of infectious diseases.40,41 Given the scarce incentives to train in these areas, the transfer of knowledge between generations of clinical microbiologists and infectious disease specialists is under threat. This problem will clearly have a negative impact on future crises and on the daily care of patients.

ConclusionsThe extent of the refugee crisis goes far beyond the human dignity and safety of displaced persons. Its reach is much wider through the spread of epidemics, political instability, and the potential emergence of violent conflicts. With respect to health in general and infectious diseases in particular, refugees are a particularly vulnerable group, as a result of the poor conditions in their country of origin and during their journey. Health care protocols must be implemented for the diagnosis and prevention of infectious diseases, while taking into account mental health, chronic conditions, and pediatric care.