Psittacosis or ornithosis is a worldwide zoonosis caused by Chlamydia psittaci (C. psittaci). Birds are the main reservoir, and transmission occurs by direct contact or by inhalation of respiratory secretions or dry faeces of infected birds.1 The cases of human psittacosis described in Spain, both sporadic and epidemic, are rare and often associated with people connected to birds.2 We report an outbreak of pneumonia due to C. psittaci, of which the focus of infection was an unauthorised centre for the sale of exotic birds.

During the months of March and April 2019, four members of the same family, residents of Murcia, went to the emergency department with a fever, severe headache, cough and general malaise. A chest X-ray was performed, observing in all of them pulmonary infiltrates located in different lobes. The haematological and biochemical parameters were normal except for C-reactive protein, which was elevated in all of them (Table 1). As a history of interest, they reported having been in direct contact with a couple of lovebirds, which had died in the days prior to them falling ill. Given the symptoms and the contact with the birds, serologies were performed for the detection of anti-C. psittaci antibodies. The serological study was performed using indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) (Chlamydophila pneumoniae IFA IgG, Vircell, Granada), collecting serum samples in the acute phase and convalescent phase (at 3 weeks).

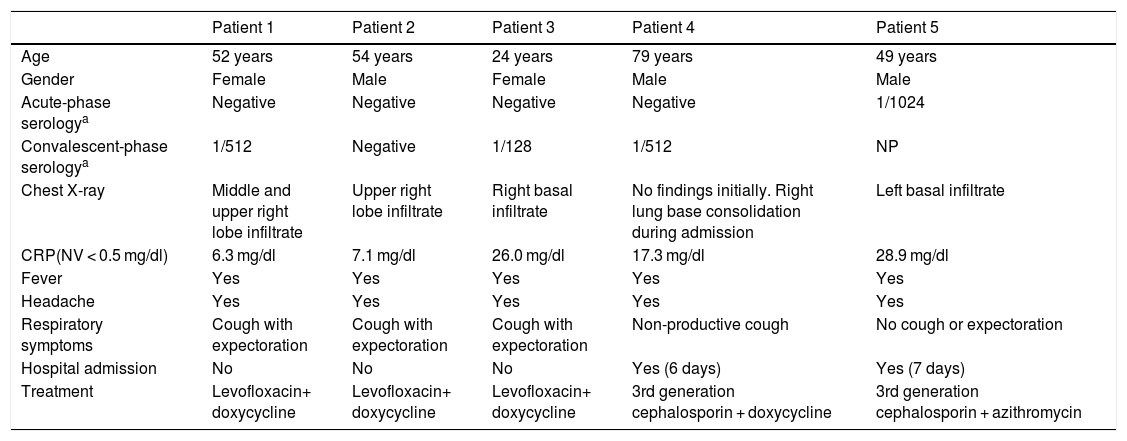

Description of cases of psittacosis.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 52 years | 54 years | 24 years | 79 years | 49 years |

| Gender | Female | Male | Female | Male | Male |

| Acute-phase serologya | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | 1/1024 |

| Convalescent-phase serologya | 1/512 | Negative | 1/128 | 1/512 | NP |

| Chest X-ray | Middle and upper right lobe infiltrate | Upper right lobe infiltrate | Right basal infiltrate | No findings initially. Right lung base consolidation during admission | Left basal infiltrate |

| CRP(NV < 0.5 mg/dl) | 6.3 mg/dl | 7.1 mg/dl | 26.0 mg/dl | 17.3 mg/dl | 28.9 mg/dl |

| Fever | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Headache | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Respiratory symptoms | Cough with expectoration | Cough with expectoration | Cough with expectoration | Non-productive cough | No cough or expectoration |

| Hospital admission | No | No | No | Yes (6 days) | Yes (7 days) |

| Treatment | Levofloxacin+ doxycycline | Levofloxacin+ doxycycline | Levofloxacin+ doxycycline | 3rd generation cephalosporin + doxycycline | 3rd generation cephalosporin + azithromycin |

CRP: C-reactive protein; NP: not performed; NV: normal value.

For the definition of cases, the criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were used3: 1) Confirmed case: clinically compatible and confirmed in a laboratory; 2) Probable case: clinically compatible and epidemiological link to a confirmed case or positive serology.

Three of the four family members had seroconversion at three weeks, while in the fourth the serology remained negative; however, he was treated as a probable case of psittacosis as he had compatible symptoms, an epidemiological relationship with the other patients, and a good response to treatment.

After the outbreak was declared, a fifth patient in contact with sick lovebirds acquired in the same centre went to the emergency department with a similar clinical picture, requiring hospital admission for respiratory distress. This person was considered a confirmed case after initial positive serology of C. psittaci.

The evolution in all cases was favourable, with a combination of doxycycline or macrolide plus a fluoroquinolone or a third-generation cephalosporin being administered as treatment.

In similar episodes that occurred in Spain, the cause of the outbreaks was contact with infected lovebirds, with the disease being contracted by both buyers and workers in hatcheries and sales centres1,4,5; however, in this case only the buyers of the birds were affected. Usually, C. psittaci infection is mild and presents as atypical pneumonia with high fever, headache and dry cough, symptoms which were present in our patients.6 However, cases of severe respiratory infection and fatal consequences in outbreaks similar to that which occurred have been reported, requiring the admission of patients in intensive care units with prolonged stays.1,4 In our case, hospital admission was only necessary in two of the patients, while the rest were treated on an outpatient basis, with good progress in all of them.

In the diagnosis of psittacosis, the clinical interview is of great importance because the symptoms that occur can be indistinguishable from other atypical pneumonias. For this reason, knowing whether the patient has been in contact with birds can be key when requesting microbiological studies that confirm it. Currently, there are no commercialised molecular techniques and carrying out cultures of C. psittaci is complex and not available to all laboratories. This makes serology, together with symptoms and epidemiology, the basis of the diagnosis of psittacosis.1,3

In this case, the microbiological diagnosis was made using serology, since the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique is not included in our laboratory's portfolio of services. A drawback of the serological diagnosis is the possible appearance of cross-reactions with other species of the genus Chlamydia. However, in our case the antibody titres against C. psittaci were high and no antibodies against other species were observed.

Tetracyclines are the treatment of choice for psittacosis; however, macrolides have been shown to be an equally effective alternative.2 All of our patients received a combination of a tetracycline or a macrolide plus a second antibiotic, with marked improvement observed in all of them.

Although psittacosis is not a disease that it is mandatory to report in Spain, we consider it advisable to report cases to epidemiological surveillance systems to perform an active search for patients and implement preventive measures that limit their spread.4

Please cite this article as: Fernández P, Iborra MA, Simón M, Segovia M. Brote de neumonía por Chlamydia psittaci en la Región de Murcia. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2020;38:300–301.