We report the case of a 75-year-old woman with a history of recurrent urinary tract infections. A barium enema, ordered for evaluation of iron deficiency anaemia, revealed a large left staghorn calculus. Renal ultrasound and intravenous urography were ordered and demonstrated a loss of ipsilateral renal function in addition to the calculus (Fig. 1). In the following months, the patient received numerous cycles of antibiotic treatment. Two years later, she presented progressive asthenia and anorexia, with weight loss of 20kg and, in the two weeks prior to admission, pain in the left renal fossa, low-grade fever and occasionally fever of up to 38.5°C. Examination of systems was normal, except for soft four-way hepatomegaly and a painful mass on the left flank. Laboratory tests revealed microcytic anaemia (haemoglobin 8.2g/dl; MCV 72.9fl), 10,800 leukocytes/mm3 with neutrophilia (87.3% segmented) and thrombocytosis (561,000 platelets/mm3). Kidney function was normal. Liver clinical chemistry showed dissociated cholestasis (GGT 49 U/l; alkaline phosphatase 247 U/l; normal total bilirubin 0.46mg/dl) with normal transaminases. Urinalysis revealed pyuria with negative nitrites, microhaematuria and mild proteinuria. Inflammation parameters were markedly elevated: C-reactive protein was 250mg/l and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 38mm/h.

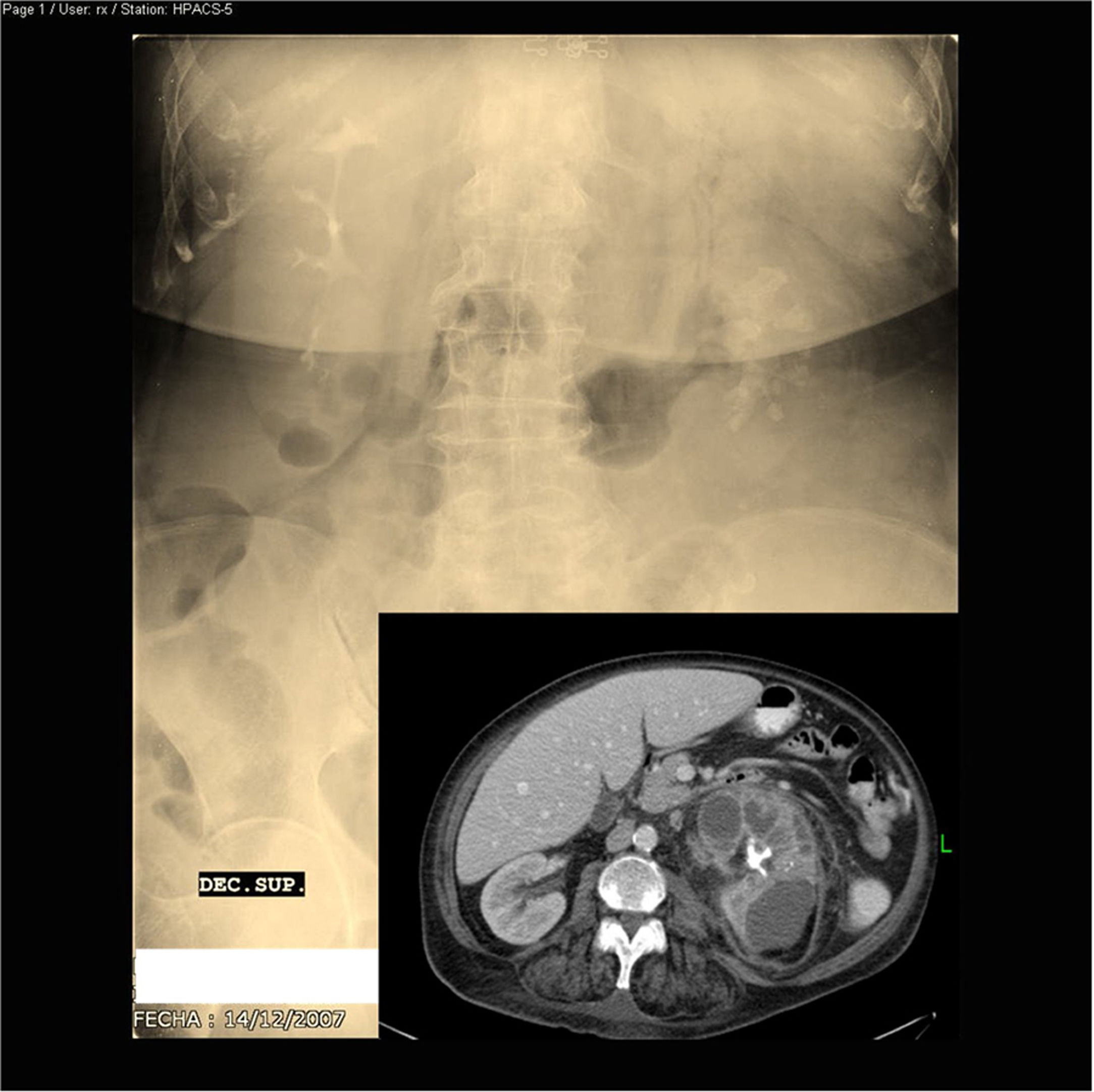

Urography: large staghorn calculus occupying practically the entire left excretory system with loss of ipsilateral kidney function and compensatory hypertrophy of the contralateral kidney. Abdominal CT scan with contrast: large calcified staghorn calculus, left nephromegaly, intrarenal collections and significant perirenal inflammatory changes.

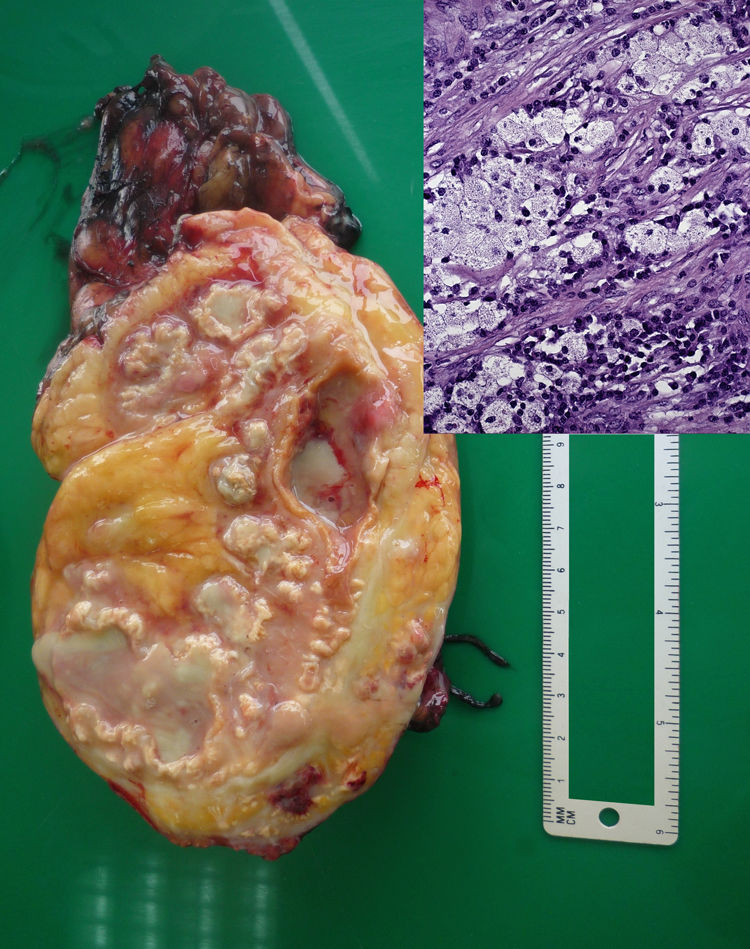

Empirical treatment with piperacillin/tazobactam was started, and the patient was afebrile on the seventh day. Blood and urine cultures, conventional and for mycobacteria, were negative. Abdominal ultrasound showed the known large calculus, mild hepatomegaly with uniform echogenicity and homogeneous splenomegaly (14.4cm). The abdominal CT scan with contrast (Fig. 1) was consistent with xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis with spread to the anterior and posterior pararenal space and left psoas with no evidence of fistulas. The right kidney was normal. A left simple nephrectomy was performed; no samples were sent for culture. The kidney was very destructured, with a large amount of purulent material and a stone occupying the pelvis and renal calyces (Fig. 2). Microscopically, fibrosis and aggregates of lipid-laden macrophages were observed, alternating with multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells (Fig. 3). This confirmed the diagnosis of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. The patient subsequently followed a satisfactory clinical course, with resolution of symptoms and normalisation of abnormal laboratory values. Ten years later, the patient was disease-free.

Macroscopic description: renal hemisection with pseudocystic dilations occupied by purulent material and yellowish–orange areas ("xanthic areas"). Microscopic description: detail of foam cells accompanied by plasma cells and lymphocytes. Haematoxylin–eosin stain. Original magnification (OM) 252×.

Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis is a chronic bacterial infection of the renal parenchyma and surrounding tissues that occurs in a context of chronic obstruction and suppuration of the renal parenchyma. From a pathology point of view, it is characterised by the appearance of large lipid-laden macrophages (foam cells).1 There are three forms: diffuse, segmental and focal. It is an uncommon disease, affecting just 18 of 3000 patients with a histological diagnosis of chronic pyelonephritis seen during a 53-year period at the Mayo Clinic (<1%).2 It can appear at any age; it predominantly appears between the fifth and seventh decades of life2–4 and mainly affects women.3–5 Time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis varies, ranging from two weeks to five years (mean of 10 months).2 There are no specific clinical findings; the most common signs and symptoms are constitutional syndrome (74%), flank pain (75%), fever (42%–69%), flank mass (11%–35%), weight loss (26%) and hepatomegaly (4%).2–5 Reactive liver clinical chemistry abnormalities ("nephrogenic liver dysfunction")2,6 are common and normalise after nephrectomy. The disease can be divided into three stages: I or renal (process confined to the kidney), II or perirenal (spread to the perirenal fat) and III or pararenal (spread to the retroperitoneum).2

A differential diagnosis should be made with adenocarcinoma, tuberculosis and kidney abscesses.5 Sample yield ranges from 57% for urine culture to 87%–100% for intraoperative culture2,6 (it is low [22%] for blood cultures).6 The most commonly isolated bacteria are Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis, with polymicrobial infection in one out of every three cases.6 There is often a discrepancy between preoperative urine culture results and renal parenchyma cultures. This point must be considered when empirical antibiotic therapy is selected.2 The treatment of choice is surgery, which is curative.5

In conclusion, xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis should be suspected in a context of recurrent urinary tract infections in patients with renal lithiasis who experience gradual clinical worsening.

FundingNot funded.

Conflicts of interestNo conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Gómez FJ, Chinchón-Espino D, Martínez-Marcos FJ, Merino-Muñoz D. Síndrome febril prolongado, dolor en flanco izquierdo y pérdida de peso en mujer con infecciones urinarias de repetición. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:254–255.