Septic thrombophlebitis of the portal vein or its branches, most often secondary to intra-abdominal infection is known as pylephlebitis. The frequency and the prognosis of this complication are unknown. The aim of this study was to determine the global and relative incidence of the most frequent intra-abdominal infections and the real prognosis of this disease.

MethodsAn observational retrospective study was conducted in a tertiary care hospital (University Hospital of Salamanca, Spain) from January 1999 to December 2008.

ResultsA total of 7796 patients with intra-abdominal infection were evaluated, of whom 13 (0.6%) had been diagnosed with pylephlebitis. Diverticulitis was the most frequent underlying process, followed by biliary infection. Early mortality was 23%. Survivors had no recurrences, but one of them developed portal cavernomatosis.

ConclusionsPylephlebitis is a rare complication of intra-abdominal infection, with a high early mortality, but with a good prognosis for survivors.

La tromboflebitis séptica de la vena porta o de sus ramas se conoce como pileflebitis. En la mayoría de ocasiones es secundaria a infecciones intraabdominales. La frecuencia y el pronóstico de esta complicación infecciosa no son conocidas. El objetivo de este estudio es describir la incidencia global, relativa y el pronóstico real de esta enfermedad respecto a las infecciones intraabdominales más frecuentes.

MétodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo en un hospital de tercer nivel (Hospital Universitario de Salamanca) desde enero de 1999 a diciembre de 2008.

ResultadosSe evaluó a 7.796 pacientes con infecciones intraabdominales. Trece (0,6%) fueron diagnosticados de pileflebitis. La diverticulitis fue el proceso subyacente más frecuente, seguida de la infección biliar. La mortalidad precoz fue del 23%. Los pacientes que sobrevivieron no presentaron recurrencias, pero uno de ellos desarrolló una cavernomatosis portal.

ConclusionesLa pileflebitis es una complicación poco frecuente de las infecciones intraabdominales. Presenta una elevada mortalidad precoz, pero tiene un buen pronóstico vital para los pacientes que sobreviven.

Pylephlebitis is septic thrombophlebitis of the portal vein or its branches.1 Although it has been described as a primary form, it normally occurs secondary to infectious intra-abdominal processes. On one hand, these are frequently accompanied by a selective bacteraemia of the mesenteric or portal veins,2 which predisposes the development of thrombosis of the portal vein or its branches. On the other hand, the infection may spread to the tree from the biliary tract or superinfected pancreatic necrosis. In addition, pylephlebitis has been seen as an iatrogenic complication secondary to liver biopsy.3

Definitive diagnosis of pylephlebitis requires percutaneous drainage of purulent material from the portal tree.4 In practice, however, the diagnosis is based on a high index of suspicion of the presence of an infectious process and visualising intra-abdominal thrombosis or gas in the portal venous system, after ruling out other potential causes of portal thrombosis.5

Existing data in the literature so far is based on case reports or short case series. It is probable that the increased use of abdominal ultrasonography and CT may be responsible for the increased number of cases of pylephlebitis diagnosed.1,5–7 However, based on these studies it is difficult to estimate the incidence, relative frequency, morbidity and the presence of late complications of different intra-abdominal infections.

The aim of this paper is to describe the incidence of pylephlebitis in our environment, and more fully understand the outcome of such infections and the associated late complications.

Patients and methodsThe design was an observational retrospective study. We reviewed the medical records from January 1999 to December 2008 in the University Hospital of Salamanca. A systematic search of pylephlebitis was made in the following diagnoses: (i) acute diverticulitis (CIE IX=562.11), (ii) acute apendicitis (CIE IX=540.9), (iii) acute cholecystitis (associated with calculi: CIE IX=574.8; without calculi: CIE IX=575.1), (iv) acute cholangitis (CIE IX=576.1), and (v) bowel perforation (CIE IX=531.9 and 532.9) only including those who had secondary peritonitis. The diagnosis of pylephlebitis was considered in the patients with the following circumstances: (i) percutaneous drainage of purulent material of portal vein or one of its branches, (ii) the existence of clinical evidence of systemic inflammatory response and radiological findings suggestive of thrombosis of the portal vein or one of its branches in the absence of other causes of portal thrombosis. We excluded patients with advanced cirrhosis, hepatoma or previous diagnosis of portal hypertension or portal thrombosis.

The BACTEC 9240 blood-culture system (Becton Dickinson Diagnostic Instrument Systems, Sparks, MD) with a standard aerobic and anaerobic medium was used in all blood samples.

In the study of thombofilia, activity antithrombin, protein C and protein S were measured by chromogenic substrate assays (HemosIL, MA, USA). FV Leiden, prothrombin 20210G>A and C677T MTHFR mutations (heterozygous mutation in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene) were demonstrated by polymerase chain reactions.8,9 Lupus anticoagulant (LA) was detected using diluted Russell's viper venom time (LAC screen, Instrumentation Laboratory). LA-positive samples were identified by mixing studies and a confirmation test (LAC confirm, HemosIL, MA, USA). An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, Diamedix Diagnostics, Inc-Florida) was used to assess aCL (IgG and IgM antibody isotypes) and anti-β2GPI. Levels of homocysteine were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography.10

We estimated the incidence of pylephlebitis in the Salamanca province out of the total population on the 1st of January 1999 (351.128 inhabitants). Statistical tests were carried out using the SPSS Statistical Package 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The results are expressed as means and SDs or medians, ranges and percentages.

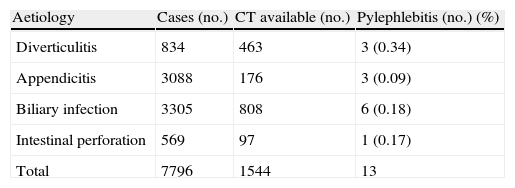

ResultsDuring the study period a total of 7796 patients with diagnoses of intra-abdominal infection were admitted (Table 1): 3305 (42.3%) patients with acute infectious disease of the biliary tract (1890 lithiasis with acute cholecystitis, acalculous acute cholecystitis 536, 879 with acute cholangitis), 3088 (39.6%) with acute appendicitis, 569 (7.2%) with abdominal perforation and 834 (10.6%) with acute diverticulitis.

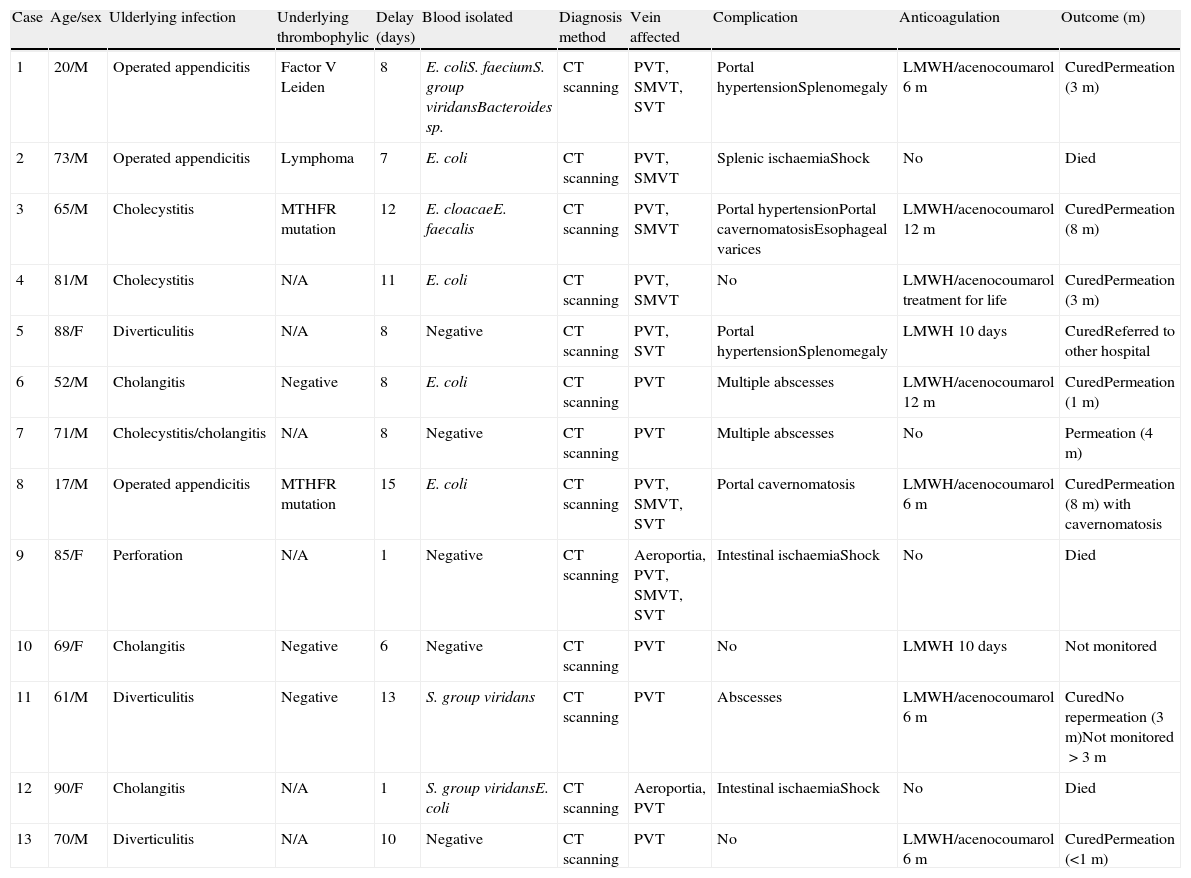

Among these patients, 0.16% of total population met the diagnostic criteria of pylephlebitis. The detected cases of pylephlebitis are summarised in Table 2. The average age of these patients was 64.7 years, with a range of 17–90 years; nine patients were male (69.2%). Pylephlebitis occurred in all the states studied, although the most frequent was in patients with diverticulitis with three cases, followed by infections of the bile duct (cholangitis and/or cholecystitis) in six cases. Pylephlebitis only complicated three (0.09%) cases of appendicitis, although only CT imaging was only performed in 5% of patients diagnosed with appendicitis. The cumulative incidence was 0.37 cases per 100,000 inhabitants/year.

Cases of pylephlebitis studied. Main clinical characteristics and evolution.

| Case | Age/sex | Ulderlying infection | Underlying thrombophylic | Delay (days) | Blood isolated | Diagnosis method | Vein affected | Complication | Anticoagulation | Outcome (m) |

| 1 | 20/M | Operated appendicitis | Factor V Leiden | 8 | E. coliS. faeciumS. group viridansBacteroides sp. | CT scanning | PVT, SMVT, SVT | Portal hypertensionSplenomegaly | LMWH/acenocoumarol 6m | CuredPermeation (3m) |

| 2 | 73/M | Operated appendicitis | Lymphoma | 7 | E. coli | CT scanning | PVT, SMVT | Splenic ischaemiaShock | No | Died |

| 3 | 65/M | Cholecystitis | MTHFR mutation | 12 | E. cloacaeE. faecalis | CT scanning | PVT, SMVT | Portal hypertensionPortal cavernomatosisEsophageal varices | LMWH/acenocoumarol 12m | CuredPermeation (8m) |

| 4 | 81/M | Cholecystitis | N/A | 11 | E. coli | CT scanning | PVT, SMVT | No | LMWH/acenocoumarol treatment for life | CuredPermeation (3m) |

| 5 | 88/F | Diverticulitis | N/A | 8 | Negative | CT scanning | PVT, SVT | Portal hypertensionSplenomegaly | LMWH 10 days | CuredReferred to other hospital |

| 6 | 52/M | Cholangitis | Negative | 8 | E. coli | CT scanning | PVT | Multiple abscesses | LMWH/acenocoumarol 12m | CuredPermeation (1m) |

| 7 | 71/M | Cholecystitis/cholangitis | N/A | 8 | Negative | CT scanning | PVT | Multiple abscesses | No | Permeation (4m) |

| 8 | 17/M | Operated appendicitis | MTHFR mutation | 15 | E. coli | CT scanning | PVT, SMVT, SVT | Portal cavernomatosis | LMWH/acenocoumarol 6m | CuredPermeation (8m) with cavernomatosis |

| 9 | 85/F | Perforation | N/A | 1 | Negative | CT scanning | Aeroportia, PVT, SMVT, SVT | Intestinal ischaemiaShock | No | Died |

| 10 | 69/F | Cholangitis | Negative | 6 | Negative | CT scanning | PVT | No | LMWH 10 days | Not monitored |

| 11 | 61/M | Diverticulitis | Negative | 13 | S. group viridans | CT scanning | PVT | Abscesses | LMWH/acenocoumarol 6m | CuredNo repermeation (3m)Not monitored>3m |

| 12 | 90/F | Cholangitis | N/A | 1 | S. group viridansE. coli | CT scanning | Aeroportia, PVT | Intestinal ischaemiaShock | No | Died |

| 13 | 70/M | Diverticulitis | N/A | 10 | Negative | CT scanning | PVT | No | LMWH/acenocoumarol 6m | CuredPermeation (<1m) |

N/A: Not available.

Delay: time between the beginning of symptoms of pylephlebitis and diagnosis.

Vein affected: PVT, portal vein thrombosis; SMVT, superior mesenteric vein thrombosis; SVT, splenic vein thrombosis.

The median time between the initial abdominal infection and hospital admission was three days (range 1–60) and the time between the final diagnosis of pylephlebitis was eight days post-admission (range 1-15). The diagnosis was made in eight patients due to the persistence of SIRS after abdominal surgery and the remaining 10 because the septic symptoms continued after conservative management with antibiotic treatment of intra-abdominal infectious process.

The radiological findings on CT of portal vein thrombosis were seen in thirteen cases and in two of these, gas was also visualised. Thrombosis affecting the superior mesenteric vein was seen in seven (53.8%) cases and in five in the splenic vein (38.4%). Ten patients diagnosed of pylephlebitis had previously ultrasound but this only detected evidence of thrombosis in four (40%).

Blood cultures were positive in eight (61.5%) patients. Microbiological agents most frequently detected were Escherichia coli in six cases (46.1%), Streptococcus viridans in three (23.0%) cases and one case of each of Bacteroides sp., Enterococcus faecium, Enterococcus faecalis and Enterobacter cloacae (7.6%). Only three (23.0%) of our patients had mixed bacteremia. Thrombophilia screening was performed in seven (53.8%) of the thirteen patients included in the study. In three (23.0%) thrombophilia was detected: one patient was heterozygous for factor V Leiden, hyperhomocysteinemia and other two patients had heterozygous mutations for MTHFR. Other prothrombotic factors predisposing to thrombosis included one case of intestinal lymphoma and one of non-cirrhotic alcoholic liver disease.

12 patients received antibiotic treatment (92.3%). Empirical antibiotics were used: (in order of frequency) five had piperacillin and tazobactam (38.4%), three were prescribed carbapenems (23.0%), two had piperacillin, tazobactam and an aminoglycoside (15.2%), or the combination of cephalosporin-metronidazole (7.6%) or a cephalosporin and ciprofloxacin (7.6%). In 9 patients, an anticoagulant treatment with LMWH (Low molecular weight heparin) was implemented and in 7 patients acenocumarol was also administrated [1 patient was transferred to another hospital] for a median of 6 moths (range 0.3–12).

Serious immediate complications secondary to pylephlebitis were observed in ten patients (76.9%): four patients had portal hypertension of whom there was one case of splenomegaly and oesophageal varices, three patients had liver abscesses, three patients had ischaemic events: one had splenic ischaemia and two had massive mesenteric ischaemia. The three patients who developed intestinal infarction died of septic shock and multiple organ failure and none of the three patients received anticoagulation given the catastrophic diagnosis.

Only two patients required drainage after diagnosis of pylephlebitis: one by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for cholangitis and one patient by endoscopic drainage of the mesenteric abscess while the remaining 11 cases (84.6%) were managed conservatively.

Seven cases (of the ten who survived the admission) were followed-up as outpatients for an average of three months (range: 10 days–8 months) but no recurrence of fever was detected in any of these patients. Reperfusion was detected in the portal system of all cases. Only one patient had radiological evidence of persistent portal vein cavernous thrombosis eight months after the episode without complications of portal hypertension.

DiscussionSeptic thrombophlebitis of the portal vein has always been considered a rare complication of intra-abdominal infection. The papers published to this date have been isolated cases or reviews of published cases in which the possibility was noted to be more common disease than previously realised.1,7 In this paper we have reviewed all the cases of pylephlebitis treated at a single hospital in 10 years. The data reported here demonstrate an incidence of 0.37 cases per 100,000 inhabitants/year. This low incidence supports the use of surgical protocols and existing guidelines of the use of broad spectrum antibiotics for treatment of intra-abdominal infections.1

In our study the relative frequency of pylephlebitis in each intra-abdominal infection was assessed. Diverticulitis appeared to be the process that most often predisposes to pylephlebitis, followed by biliary tract infections and less commonly, appendicitis. This has already been suggested by others, as opposed to the first studies that highlighted appendicitis as the main predisposing factor.1,7 It is likely that initial conservative treatment with antibiotics in diverticulitis and biliary tract infections, compared with early surgery for appendicitis, may contribute to the increased frequency of this complication. However, it should be noted that only 5% of patients with appendicitis underwent CT imaging, so subclinical pylephlebitis cannot be excluded despite good prognosis associated with appendicitis.

The co-existence of other prothrombotic factors that could facilitate the development of septic thrombophlebitis were also studied. Thus three thrombophilias (inherited and acquired) were detected within the seven patients investigated. Clear links have already been established between the presence of the MTHFR mutation and Factor V Leiden or lymphoma detected here and the development of intra-abdominal thrombosis. These data are somewhat higher than those reported in other series in which about 30% have other prothrombotic factors associated primarily neoplasias.7

Liver disease has been considered in some studies as the most important predisposing factor for the diagnosis of pylephlebitis: up to 50% of cases of pylephlebitis have been associated with a severe liver disease, cirrhosis or hepatoma.11 In our series only one patient (7.6%) had hepatic steatosis in liver disease. This lower frequency observed is because we excluded patients with advanced liver cirrhosis or hepatocarcinoma,12 who may have up to 8–25% thrombosis of the portal system not linked to a pylephlebitis.12,13

The normal clinical setting of pylephlebitis was the persistence of SIRS after diagnosis of intra-abdominal infection despite continuing medical or surgical input. The median delay from onset of primary symptoms to the diagnosis of pylephlebitis was eight days and in two patients the diagnosis was the same day as the start of clinical episode. This reflects that the process of infection usually occurs early despite delay in the diagnosis of the primary infection. This is shown in the work of Juric in which bacteremia is detected selectively in the portal system in the early stages of appendicitis.2

In our paper we reviewed the requested blood cultures in our patients that detected 61.5% positivity. This positivity rate is similar to that detected in some series7 and is remotely reflective of the 88% positivity seen in the Plemmons series.1 This high percentage of positivity may be due to publication bias. It is also possible that the use of empirical antibiotic therapy prior to extraction of blood culture in any patient in our centre has contributed to a lower frequency of positivity. Although as described, the infection is often polymicrobial, only three of our patients had mixed bacteremia. The organism most often implicated in our series was E. coli (six cases) followed by three cases of S. viridans. These same agents are those most frequently detected in the bacteremias of patients with apendicitis2 and in published case series.1,7,11

Treatment after diagnosis consisted of broad-spectrum antibiotics and anticoagulants. Only two patients required surgical invasive treatment (for mesenteric intra-abdominal abscess) and endoscopic sphincterotomy (cholangitis secondary to choledocholithiasis).

In terms of immediate complications detected, the most frequent were multiple liver abscesses and radiological evidence of portal hypertension (splenomegaly, esophageal varices and cavernous portal). In the same way as reported in the literature, no patient had symptoms of portal hypertension (variceal bleeding, gross ascites or hypersplenism).

Overall mortality in our study was 23%; similar to other retrospective series, described between 19 and 32%.1,7 In our series, we found an association between anticoagulation and mortality (100% non-anticoagulated mortality vs 0% in the anticoagulated). This association is due to an obvious selection bias, due to the catastrophic deterioration in these patients with shock and multiorgan failure that did not allow time for early initiation of anticoagulant therapy before the patient died. The small number of patients determines the conclusions of our work. Indeed, death may be due to other causes.

A recent retrospective study also showed a lower mortality among patients who received anticoagulant therapy, although the information in the study did not exclude obvious selection bias of patients.7 No patients received percutaneous drainage of the portal vein, a technique that has proven effective in the diagnosis and treatment of this pathology.4

Follow-up after discharge of survivors occurred for seven of the ten surviving patients with a median time of twelve weeks. No patients had evidence of recurrence of infection and in all those in whom reperfusion was detected, none displayed clinical signs of portal hypertension. Reperfusion was detected in 14% of non-anticoagulated and 25% of the anticoagulated.7 This high degree of reperfusion detected in our series compared with previous series justifies the exclusion of patients with chronic portal vein thrombosis and favours an early diagnosis and treatment of our patients.

In conclusion, pylephlebitis remains an uncommon disease in intra-abdominal infections with high morbidity and early mortality; nevertheless, prolonged treatment with antibiotics and anticoagulants is associated with a low recurrence rate and a high probability of reperfusion of the portal system.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

We are grateful to Elisabeth Kane for their help with the translation.