We analyzed epidemiological, clinical characteristics, and the response to treatment in people living with HIV (PLHIV) who recently acquired hepatitis C (RAHC) in a multicentre study in Madrid (Spain).

MethodsMulticenter, ambispective, observational study of RAHC in men who have sex with men (MSM) infected with HIV. Clinical, epidemiological, and RAHC evolution were recorded prospectively in 2019 and 2020 and retrospectively in 2017 and 2018. In patients who received HCV treatment, sustained virological response (SVR) was provided 12 weeks after the end of treatment in an intention to treat analysis (ITT): all treated patients were included; and in analysis per-protocol (PP): missing patients were excluded.

ResultsOverall, 133 patients were included. Median (IQR) age was 40 (34.3–46.1) years, 90.9% had at least one previous sexual transmission disease (STD), and 33.6% had previously hepatitis C. More than half of the prospective sample included patients using chemsex related drugs (57.3%), 45.7% of them intravenously. The most prevalent genotype was G1a (66.2%), followed by G4 (11.3%). Ten of 90 patients evaluated for spontaneous cure (11%) cured the infection spontaneously, and 119 had treatment after a median time of 1.8 (0.7–4.6) months: sustained virological response (SVR) was achieved in 90.7% in the ITT and 94.7% in the PP analysis, with no differences regarding the direct-acting antiviral agents (DAA) combination used.

ConclusionsMSM infected by HIV with a RAHC were exposed to high-risk sexual behavior. Spontaneous cure rate was low, while SVR after treatment was achieved by more than 90%.

El objetivo de nuestro estudio fue analizar las características epidemiológicas, clínicas y la respuesta al tratamiento en personas que viven con VIH (PVIH) con hepatitis C recientemente adquirida (HCRA).

MétodosEstudio observacional multicéntrico que incluye PVIH, hombres que tienen sexo con hombres (HSH), con una HCRA durante los años 2017 y 2020 en Madrid. Los datos se recogieron prospectivamente los años 2019 y 2020 y retrospectivamente los años 2017 y 2018. En los pacientes que recibieron tratamiento se calculó la respuesta viral sostenida (RVS) a las 12 semanas de acabar el tratamiento en un análisis por intención de tratar (IT) (incluye todos los pacientes) y por protocolo (PP) (excluye las pérdidas).

ResultadosSe incluyeron 133 hombres: edad mediana (RIQ) 40 (34,3-46,1) años, 90,9% con antecedentes infecciones de transmisión sexual (ITS) y 33,6% con hepatitis C previa. Los pacientes incluidos prospectivamente rellenaron una encuesta sobre hábitos tóxicos y 57,3% declaró haber practicado chemsex (45,7% de estos por vía intravenosa). Los genotipos más frecuentes fueron el G1a (66,2%) y el G4 (11,3%). Tan sólo 10/90 pacientes evaluados (11%) curaron sin tratamiento. Tras una mediana de 1,8 meses (0,7-4,6), 119 pacientes recibieron tratamiento (43 de manera precoz y 76 tras evaluar posible curación espontánea). La RVS fue 90,8% (IT) y 94,7% (PP). No observamos diferencias en los diferentes regímenes de antivirales de acción directa usados.

ConclusionesLos HSH con infección por VIH con HCRA en Madrid están expuestos a prácticas sexuales con alto riesgo de ITS y reinfección del VHC. La curación espontánea es baja, mientras que la respuesta al tratamiento es mayor al 90%.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has an ambitious program to eliminate viral hepatitis as a major public health threat by 2030. Specifically, a 90% reduction in new hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections and a 65% reduction of HCV-related deaths should be achieved by 2030.1 Due to the efficacy and tolerability of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAA), this plan should be possible; however, significant challenges as access to affordable diagnosis and treatment programs (mainly in low and middle-income countries) are required to afford this plan.2

Another challenge for HCV elimination is the epidemic of HCV infections and reinfections described within the last two decades in men who have sex with men (MSM) in multiple metropolitan areas throughout the world.3–6 To address this problem, some recent guidelines recommend early treatment of recently acquired HCV (RAHC), especially in a population at higher risk of transmission.7–9 On the one hand, recent data from modeling studies and population cohorts suggest that an immediate treatment after HCV diagnosis may be a cost-effective strategy when including prevention benefits.10,11 On the other hand, although data are still scarce, the rates of response to RAHC treatment with DAA show very high cure rates.12–14

The objectives of our study were, first, to describe sociodemographic characteristics of PLHIV with RAHC in the Madrid area; second, to determine spontaneous cure in patients who did not start treatment very early; and third rates of sustained virological response (SVR) in patients who started treatment with DAA.

MethodsOurs was a multicenter, ambispective, observational study conducted in the city of Madrid (Spain). Eligible patients were MSM or transexual women, 18 years of age or older who had a documented HIV infection and a RAHC diagnosed since January 2017 to December 2020. RAHC was defined according to the European Treatment Network for HIV, Hepatitis and Global Infectious Diseases (NEAT-ID) Consensus Panel definition of recently acquired hepatitis C virus infection.9 This is, having a positive anti-HCV IgG and a documented negative anti-HCV IgG in the previous 12 months or a positive HCV-RNA with a documented negative HCV-RNA or negative anti-HCV IgG in the last 12 months.

Eight centers in the public health system of the Madrid area participated in the study. The study had two phases. From January 1, 2019, to December 31, 2020, RAHC patients were invited to participate and prospectively enrolled the study. Patients diagnosed with RAHC between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2018, were retrospectively reviewed.

Sociodemographic characteristics (age, race, place of birth), HIV-related variables (years since diagnosis, stage of infection, CD4 T cell lymphocytes count, and HIV viral load), and a history of sexually transmitted diseases (STD) were recorded in the entire sample. In addition, prospectively included participants completed a self-reported survey that included questions about sexual behaviors (number of sexual partners, condom use, receptive anal sex, fisting practices), general drug use, and the use of chemsex related drugs within the last six months. The use of chemsex related drugs was considered when participants used mephedrone or other cathinones, crystal methamphetamine, or y-hydroxybutyrate (GHB)/y-butyrolactone (GBL). They also completed the Spanish version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HADS) to assess anxiety and depression symptoms and answer questions about the way they thought they became infected with HCV.15

Concerning hepatitis C characteristics, HCV-RNA viral load and HCV genotype, were recorded. In the prospective phase of the study, a sample was collected and saved for subsequent phylogenetic analysis.

EvolutionA spontaneous cure was evaluated in patients who had at least two HCV-viral load measurements separated by at least one month. When there was not a decrease of at least 2 log of HIV-RNA during the first month or undetectable HCV-RNA at month 6 spontaneous clearance was excluded. Patients who started treatment as soon as the diagnosis was performed were excluded from this analysis as spontaneous HCV clearance could not be excluded.

In patients treated with DAA, the time from diagnosis to treatment and type of DAA combination used were recorded.

Sustained viral response (SVR) was defined as an undetectable HCV RNA, 12 weeks after treatment. Results were given as intention to treat (ITT) analysis and as per-protocol (PP) analysis, where missing patients were excluded.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies; continuous variables were expressed as median and interquartile ranges (IQR). Baseline characteristics between retrospective and prospective patients included in the study were compared using the Chi-squared or Fisher exact test for categorical variables and the T-test for continuous variables. A comparison of SVR regarding the DAA used was performed using the χ2 test.

ResultsBaseline characteristics133 patients of 8 different centers were included in the study: 34 in 2017, 32 in 2018, 39 in 2019, and 28 in 2020.

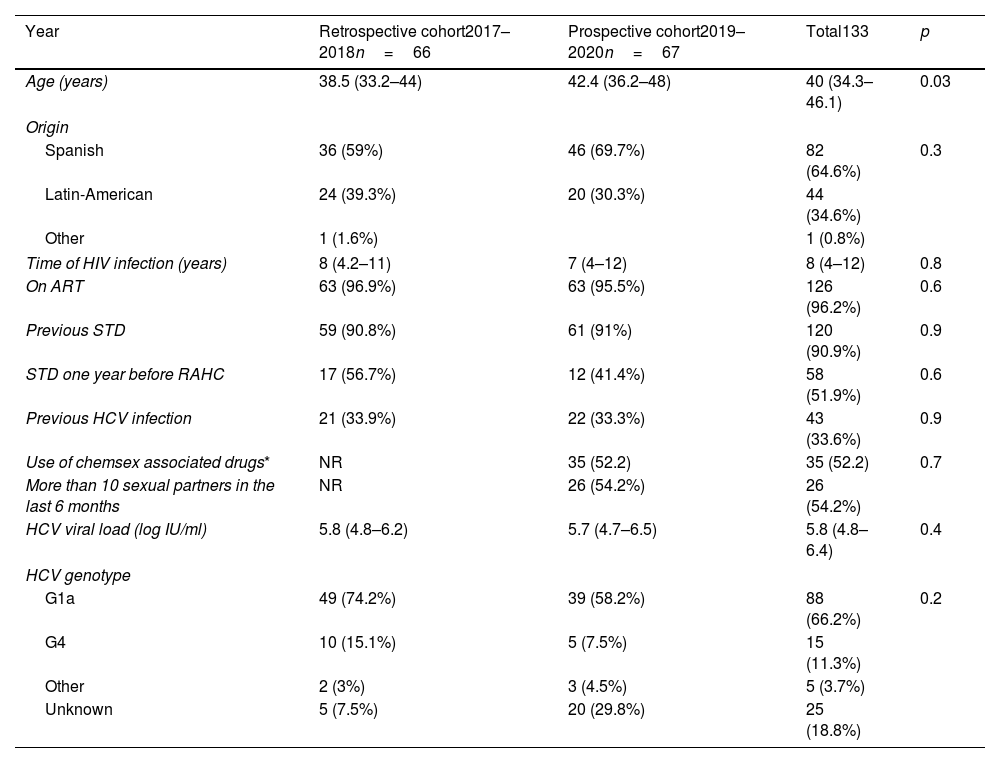

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Median age (IQR) and median time since HIV diagnosis were 40 (34.3–46.1) and 8 (4–12) years, respectively. Overall, more than 90% of the patients had at least one STD, and 33.6% had previously hepatitis C. The most prevalent HCV genotype was G1a in 66.2% of the cases, followed by G4 (11.3%). The median baseline HCV viral load was 5.8 log10 IU/ml.

Characteristics of HIV infected MSM with recently acquired hepatitis C in Madrid.

| Year | Retrospective cohort2017–2018n=66 | Prospective cohort2019–2020n=67 | Total133 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38.5 (33.2–44) | 42.4 (36.2–48) | 40 (34.3–46.1) | 0.03 |

| Origin | ||||

| Spanish | 36 (59%) | 46 (69.7%) | 82 (64.6%) | 0.3 |

| Latin-American | 24 (39.3%) | 20 (30.3%) | 44 (34.6%) | |

| Other | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | ||

| Time of HIV infection (years) | 8 (4.2–11) | 7 (4–12) | 8 (4–12) | 0.8 |

| On ART | 63 (96.9%) | 63 (95.5%) | 126 (96.2%) | 0.6 |

| Previous STD | 59 (90.8%) | 61 (91%) | 120 (90.9%) | 0.9 |

| STD one year before RAHC | 17 (56.7%) | 12 (41.4%) | 58 (51.9%) | 0.6 |

| Previous HCV infection | 21 (33.9%) | 22 (33.3%) | 43 (33.6%) | 0.9 |

| Use of chemsex associated drugs* | NR | 35 (52.2) | 35 (52.2) | 0.7 |

| More than 10 sexual partners in the last 6 months | NR | 26 (54.2%) | 26 (54.2%) | |

| HCV viral load (log IU/ml) | 5.8 (4.8–6.2) | 5.7 (4.7–6.5) | 5.8 (4.8–6.4) | 0.4 |

| HCV genotype | ||||

| G1a | 49 (74.2%) | 39 (58.2%) | 88 (66.2%) | 0.2 |

| G4 | 10 (15.1%) | 5 (7.5%) | 15 (11.3%) | |

| Other | 2 (3%) | 3 (4.5%) | 5 (3.7%) | |

| Unknown | 5 (7.5%) | 20 (29.8%) | 25 (18.8%) | |

ART: antiretroviral drugs; STD: sexually transmitted diseases; RAHC: recently acquired hepatitis C.

Comparison between prospective and retrospective cohorts in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in any baseline characteristics except for age: patients included in the prospective cohort were older.

Regarding self-reported data completed by patients prospectively included (n=67), 61 participants completed valid drug-related questions. Of them, 57.3% (n=35) reported the use of chemsex related drugs in the last 6 months: cathinones (54.1%), GHB (47.6%), cocaine (27.9%), methamphetamine (26.2%), ketamine (6.4%) and ectasis (1.5%). None of the patients reported having used heroin. In the last six months, sixteen patients (26.2%) had used drugs intravenously and 6 (9.8%) anally.

Furthermore, 47 patients answer valid questions about sexual risk behaviors. Of them, 45 (91.8%) had unprotected anal sex, 26 (54.2%) had had more than ten sexual partners, and 13 (27.7%) had practiced fisting in the last six months. Forty-five patients answered a question about possible modes of having acquired HCV infection: 37 (82.2%) thought they could have acquired it by sexual relationship, 5 (11.1%) by sharing needles or other injection drug use material, 9 (7.1%) by sharing sex toys or similar objects and 11 (8.7%) by sharing material while snorting drugs.

Finally, 46 participants completed valid HADS for screen anxiety and depression. Of them, 22 (47.8%) had scores suggestive of clinical mood disorders (depression sub-scale scores >8) and 16 (34.8%) suggestive of possible clinical anxiety (anxiety sub-scale scores >8).

RAHC evolutionOnly 90 patients could be evaluated for spontaneous cure (those who had at least two HCV-viral load measurements separated by at least one month before starting HCV treatment). Ten of them spontaneously cleared HCV: 11% (95% CI 0.6–20). Among the other 123 patients (90 without spontaneous cure and 43 with early treatment), 119 started treatment, and 4 were lost of follow-up before HCV treatment.

Treatment was started at a median time of 1.8 months (0.7–4.6) since the diagnosis. DAA used was Elbasvir/Gazoprevir in 10 patients, Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir in 29, Glecaprebir/Pibrentasvir in 46, Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir in 31 and Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir/Voxilaprevir in 3.

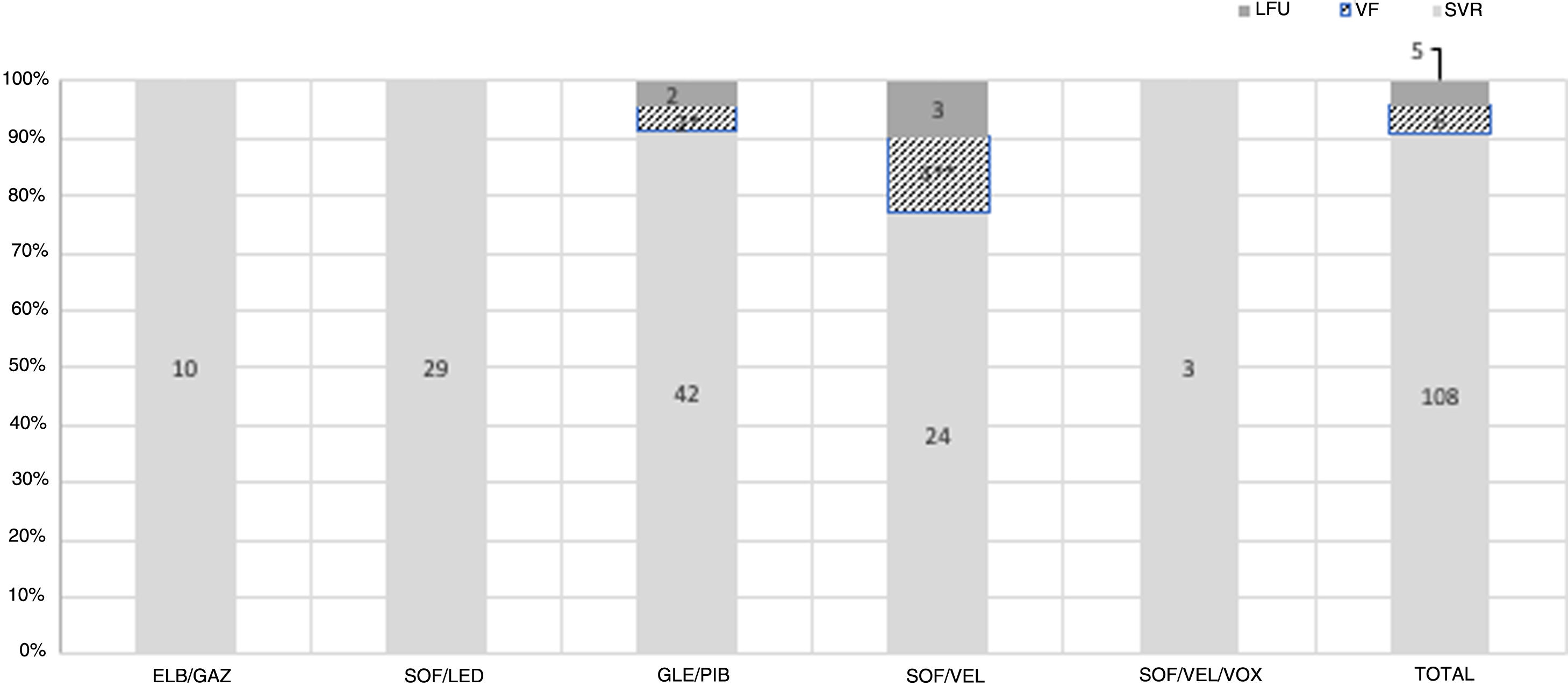

SVR was 90.7% (108/119) in the ITT analysis and 94.7% (108/114) in the PP analysis. Six patients had HCV relapse 12 weeks after completing treatment. All relapses were with the same genotype. Reinfection could not be ruled out in four of them, as patients recognized having recent high-risk sexual practices or the diagnosis coincided with another STD. Finally, 5 patients were lost to follow-up. There were no statistical differences in SVR regarding the DAA combination used (p=0.7) [Fig. 1].

Treatment response in recent hepatitis C infected PLHIV. PLHIV: people living with HIV; SVR: sustained virologic response; VF: virologic failure; LFU: lost to follow-up; ELB/GAZ: Elbasvir/Grazoprevir; SOF/LED: Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir; GLE/PIB: Glecaprebir/Pibrentasvir; SOF/VEL: Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir; SOF/VEL/VOX: Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir/Voxilaprevir. *Possible reinfection; **two possible reinfections, 1 bad adherence; ***no statistical differences were seen between different treatment used.

There were no significant differences in SVR regarding HCV genotype in the ITT analysis. SVR in the most prevalent genotypes were: 89.7% (70/78) in G1a and 100% (12/12) in G4 (p=0.7). Only two patients were G3 infected, and both were treated with SOF/VEL. One of them achieved SVR, and the other was lost to follow-up. Baseline HCV viral load was neither associated with SVR: β 0.76 (0.54–1.56) for every log HCV increase (p=0.9).

DiscussionDeclines in HCV incidence and prevalence in MSM living with HIV have been reported in some countries such as Australia16 and Germany since the broad implementation of HCV treatment programs. Although Spain is one of the countries with the highest rates of HCV treatment and elimination,17 especially among PLHIV18 we did not observe this decrease in RAHC. Since 2016 Spain has had universal and unrestricted treatment for hepatitis C, which allowed us to carry out this study to assess the impact of treatment on high-risk people in the next years.

Absolute numbers of RAHC infections did not decrease during the last four years in 8 HIV reference centers in Madrid and were usually accompanied by risky sexual practices and other STIs. In 2020, we observe a slight decrease in the cases, although this is likely due to the lack of clinic visits due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to confinement policies in 2020, a greater decrease in cases should be expected. We believe multiple reasons can explain the lack of decrease cases observed in our population. First, as previously reported, RAHC appeared in MSM-PLHIV with high-risk sexual behaviors.20,21 The acquisition of hepatitis C has been associated with risky sexual practices such as condomless anal sex, fisting, or having a high number of casual sexual partners co-existence of other STDs and other risky practices such as recreational drug use during sex (including intravenous drug use). As in previous studies, our entire sample had high rates of having had at least another STD in their lifetime and the previous year to HCV diagnosis (90 and 52%, respectively). Moreover, the data collected in our group of patients prospectively included show high rates of condomless (92%), fisting practice (28%), a high number of casual sexual partners (54%), and use of chemsex related drug use (57%). Interestingly, most patients thought they had been infected by HCV during sexual relationships, but nearly 10% associated it with sharing needles, snorting paraphernalia, or sexual toys. These data highlight the need for multidisciplinary sexual health programs and a holistic approach to address this problem. Second, a hidden undiagnosed HCV population may be acting as a reservoir. In this context, some HIV-negative MSM have similar sexual risk practices and risk of HCV acquisition, but unlike HIV-infected MSM, STD screening is less frequent as they do not always routinely engage with the health care system.19,20

HCV re-infection either after spontaneous clearance or treatment-induced sustained viral response is a well-recognized phenomenon, especially in HIV-positive MSM with ongoing risk behaviors. In our sample, 43 (33.6%) patients from the retrospective and prospective cohorts had an HCV reinfection. Similar data have also been reported in the German GECCO cohort6 and the Madrid-Core21 (reinfection rates of 5.93 patients-years among MSM HIV infected). In Madrid-Core, reinfections have been detected a median of 15 weeks after SVR, suggesting that patients continued to engage in risk behaviors shortly after or even during DAA therapy. Identifying new HCV infections should be based on whether the individual engages in risky activities associated with HCV transmission. However, the high rate of HCV reinfection in MSM underlines the difficulties in changing or modifying ongoing risk behavior. Fortunately, early HCV treatment as prevention has been followed by a dramatic decrease in new HCV infections in recent study reports from different countries in Europe.11,22

Since we did not have paired pre-and post-treatment samples, we could not classify rebound of viral load as relapse or reinfection. A phylogenetic study was not carried out in six patients who relapsed with the same genotype. In fact, in 4 of the 6 patients, the diagnosis of reinfection was the most likely as they recognized high-risk sexual practices or RAHC diagnosis was concurrent with other STDs.

Over the last decade, the advent of efficacious and well-tolerated oral DAA treatments dramatically altered the treatment paradigm in chronic hepatitis C, increasing cure rates to more than 95%.7 Guidelines for chronic HCV infection generally recommend using pan-genotypic regimens wherever possible because of their very high efficacy and the ability to avoid genotyping. Data on the two pan-genotypic regimens of Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir and Glecaprevir/Pibrentasvir in the setting of recent infection are currently limited. A total of 108 patients with RAHC received antiviral treatment in a median time of less than two months from diagnosis. This is facilitated by universal access to therapy in our region and clinicians’ awareness of the need for early treatment in high-risk groups. Efficacy by intention-to-treat was very high (SVR >90%) and comparable to other studies in people with HIV. No differences were observed between the different DAA used, suggesting that any regimen used for chronic hepatitis C is useful for RAHC. Although there are few data on treatment response to DAA for RAHC in clinical trials, they show high rates of SVR. For example, 8 weeks of SOF/LED obtained an SVR of 100% in 27 PWHIV12 and 8 weeks of ELB/GAZ obtained an SVR of 99% in 80 patients.23 According to these data and ours, an Austrian clinical setting study showed 100% of SVR in 38 RAHC PLHIV, treated with different combinations following recommendations for chronic hepatitis C treatment.24 Treatment was well-tolerated, and there were no treatment interruptions due to adverse events. On note, 3 patients received SOF/VEL/VOX although this regimen is indicated as second line after treatment failure. All three cases were reinfections and not relapses (negative HCV-RNA was observed 3 months after the end of the previous treatment) but their doctors decided to prescribe this treatment.

On the contrary, a spontaneous cure is low, 11% in our cohort, like other reports. Rates of spontaneous viral clearance in HIV-positive MSM with recently acquired hepatitis C in the large PROBE-C cohort have been low at 11.8%.25 This proves that following a recently acquired HCV infection, transition to chronic hepatitis C is the most common outcome in individuals with or without HIV infection. With the high rates of treatment SVR and the high rates of reinfection in this high-risk population, this data suggests that treatment deferral to await spontaneous clearance might not be justified. Treatment delays may lead to HCV transmission in the setting of ongoing risk behavior.

Our study has some limitations. First, to have a follow-up over the years, we had to include years 2017 and 2018 retrospectively. We acknowledge that data collection rigor is not the same. However, all HCV infected patients who received treatment in Madrid have to be included in a compulsory prospective registry.25 For this reason, we do not believe we have missed any patients with RAHC, at least those who have received treatment. Second, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, patients had fewer clinical visits; therefore, the number of cases in 2020 may have been underestimated. However, we believe that our data shows that RAHC in HIV-MSM with high-risk sexual behaviors continues to be an important handicap in terms of HCV elimination in developed countries. Our study also highlights the high rates of SVR in RAHC treated very early in a clinical setting.

In conclusion, we did not observe a decrease in RAHC cases among HIV-MSM with high-risk sexual practices since the implementation DAA treatment. Spontaneous cure rates are low, while SVR after treatment is above 90%. Our results reinforce recent recommendations of AASLD and EACS guidelines for initiating HCV treatment as soon as possible, without waiting for spontaneous resolution.

Ethical approvalThe study was approved by La Paz Hospital Ethics committee. All patients were informed before any study procedure was performed and signed informed consent. Study data were all anonymized and collected using the tool Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) hosted at “Association Ideas for Health”.26 All research was carried out following the right to privacy, as stipulated in the Organic Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of April 27, 2016, on data protection (GDPR), on the protection of personal data, and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Authors’ contributionsProtocol design: LMC, AGB, SR, JHG, PR.

Patient selection, include data on base-data: LMC, AG, OB, JV, CR, MJV, JS, BA, MP, IS, PR.

Statistical analysis: LMC, PR.

Sample processing: SR, DSC.

Manuscript writing: LMC, AGB, PR.

Manuscript review: All

English review: JCS

FundingThis study was partially supported by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III/ISCIII: PI20/00474 and PI20/00507.

Competing interestsThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.