To analyze the cases of acute mastoiditis, characteristics, management and complications in children attended in the emergency department.

MethodsRetrospective study of acute mastoiditis in a Spanish tertiary hospital over a 6-year period (2018–2023).

ResultsOne hundred two episodes of acute mastoiditis were analyzed (54% males, median age 1.8 years). Microorganisms were isolated in one third of cases, mainly Streptococcus pyogenes (64% of ear secretion cultures). Complications occurred in 27.5%, primarily subperiosteal abscess. A younger age, absence of vaccination schedule, previous history of otitis, cochlear implant carriers or white blood cell counts and C-reactive protein levels were not associated with complications. Complicated cases had longer hospitalizations. Treatment included antibiotics, corticosteroids, and surgery in 50% of cases.

ConclusionsThis study shows an increase of acute mastoiditis during 2023, with a relevant role of S. pyogenes. A younger age, absence of vaccination, personal history of otitis or cochlear implant, blood cell counts and C-reactive protein levels were not associated with complications.

Analizar los casos de mastoiditis agudas, características, manejo y complicaciones en niños atendidos en urgencias.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo en un hospital terciario en España durante 6 años (2018-2023).

ResultadosSe analizaron 102 episodios de mastoiditis aguda (54% varones, mediana de edad de 1,8 años). Se aislaron microorganismos en un tercio, principalmente Streptococcus pyogenes (64% de cultivos óticos). Hubo complicaciones en el 27,5%, mayoritariamente abscesos subperiósticos. No observamos más complicaciones en niños <2 años, aquellos con calendario vacunal incorrecto, antecedentes de otitis, portadores de implante coclear o aquellos con alteraciones analíticas (leucocitosis, elevación de proteína C reactiva). Los casos complicados tuvieron hospitalizaciones más prolongadas. El tratamiento incluyó antibioterapia, corticoterapia y cirugía en el 50% de los casos.

ConclusionesComunicamos un aumento de casos de mastoiditis aguda en 2023, con relevancia de S. pyogenes. Factores como la edad, estado vacunal, antecedentes de otitis o implante coclear y parámetros sanguíneos no se relacionaron con complicaciones.

Acute mastoiditis is the most frequent complication of acute otitis media (AOM); however, it is an uncommon occurrence. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes are the most common causative agents.1

Reports describing the incidence of acute mastoiditis in children are contradictory as to whether the incidence is rising.2–4 In recent years, different strategies for management of AOM have been established, such as the “watchful waiting approach” versus upfront antibiotic treatment,5 which may also influence rates of complications. It is also debated whether the incidence of acute mastoiditis is increasing due to the rise of antibiotic resistance6 or whether the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced.7 In addition, since December 2022, several countries published an alert on the increase of cases of S. pyogenes infections in children,8,9 which must be considered.

Given the limited data available on pediatric mastoiditis cases, our objective was to analyze the cases of acute mastoiditis, clinical characteristics, management and complications in children admitted to the Pediatric Emergency department (PED) of a tertiary hospital.

MethodsRetrospective study performed over a period of 6 years (from January 2018 to December 2023) in a tertiary hospital of Madrid (Spain). The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Clinical Research (PI-5996). Patients attended in the PED with a final diagnosis of acute mastoiditis were included. To establish the diagnosis, all patients were assessed by a pediatrician and an otolaryngologist. Demographic and clinical data were obtained from the electronic medical record system.

Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 20 program. The results are presented as absolute frequencies and percentages. Quantitative data are expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test, and continuous variables were compared with non-parametric tests. p values under 0.05 were considered significant.

ResultsDuring the study period, 102 episodes of acute mastoiditis in 96 patients were registered (six patients presented two episodes). Fifty-four percent were male, with a median age of 1.8 years (IQR 1.8–3.3 years). Ninety-seven percent of the cases (n=99) had the appropriate vaccination schedule, and 34.3% (n=35) had previously experienced AOM (nine patients had a history of mastoiditis). Eleven patients (10.8%) were cochlear implant recipients and four patients (3.9%) had craniofacial abnormalities.

Thirty-one cases (30.4%) had recently received the diagnosis of AOM in the current process, and 31 (30.4%) were receiving oral antibiotic treatment, mainly amoxicillin and amoxicillin–clavulanate (93.5%).

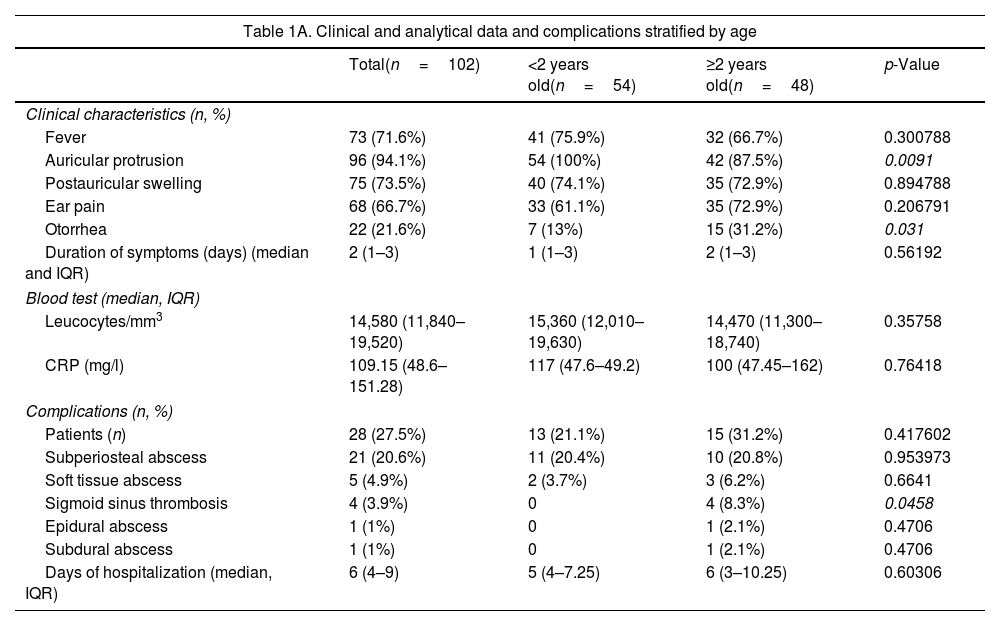

Table 1A summarizes the clinical and analytical characteristics and complications of the patients and compares them by age strata. Upon physical examination, bulging tympanic membrane was detected in 40 episodes (39.2%), and in almost a quarter (24.5%) the tympanic membrane could not be visualized.

Clinical and analytical characteristics and complications of the patients.

| Table 1A. Clinical and analytical data and complications stratified by age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total(n=102) | <2 years old(n=54) | ≥2 years old(n=48) | p-Value | |

| Clinical characteristics (n, %) | ||||

| Fever | 73 (71.6%) | 41 (75.9%) | 32 (66.7%) | 0.300788 |

| Auricular protrusion | 96 (94.1%) | 54 (100%) | 42 (87.5%) | 0.0091 |

| Postauricular swelling | 75 (73.5%) | 40 (74.1%) | 35 (72.9%) | 0.894788 |

| Ear pain | 68 (66.7%) | 33 (61.1%) | 35 (72.9%) | 0.206791 |

| Otorrhea | 22 (21.6%) | 7 (13%) | 15 (31.2%) | 0.031 |

| Duration of symptoms (days) (median and IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 1 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.56192 |

| Blood test (median, IQR) | ||||

| Leucocytes/mm3 | 14,580 (11,840–19,520) | 15,360 (12,010–19,630) | 14,470 (11,300–18,740) | 0.35758 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 109.15 (48.6–151.28) | 117 (47.6–49.2) | 100 (47.45–162) | 0.76418 |

| Complications (n, %) | ||||

| Patients (n) | 28 (27.5%) | 13 (21.1%) | 15 (31.2%) | 0.417602 |

| Subperiosteal abscess | 21 (20.6%) | 11 (20.4%) | 10 (20.8%) | 0.953973 |

| Soft tissue abscess | 5 (4.9%) | 2 (3.7%) | 3 (6.2%) | 0.6641 |

| Sigmoid sinus thrombosis | 4 (3.9%) | 0 | 4 (8.3%) | 0.0458 |

| Epidural abscess | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (2.1%) | 0.4706 |

| Subdural abscess | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (2.1%) | 0.4706 |

| Days of hospitalization (median, IQR) | 6 (4–9) | 5 (4–7.25) | 6 (3–10.25) | 0.60306 |

| Table 1B. Comparison between patients with complications and patients without complications | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total(n=102) | Complications(n=28) | No complications(n=74) | p-Value | |

| Age <2 years | 54 | 13 (46.4%) | 41 (55.4%) | 0.417602 |

| Age ≥2 years | 48 | 15 (53.6%) | 33 (44.6%) | 0.417602 |

| Inadequate vaccination | 3 | 2 (7.1%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0.182 |

| Previous history of otitis | 35 | 10 (35.7%) | 25 (33.8%) | 0.854585 |

| Cochlear implant carriers | 11 | 2 (7.1%) | 9 (12.2%) | 0.7229 |

| Leucocytes/mm3 (median, IQR) | 14,580 (11,840–19,520) | 14,400 (7,500–20,600) | 14,870 (12,450–18,700) | 0.35758 |

| CRP (mg/dl); median (IQR) | 109.15 (48.6–151.28) | 157 (62.1–264.6) | 96.7 (48.5–131.9) | 0.76418 |

| Duration of symptoms (days) (median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3.7) | 2 (1–3) | 0.08012 |

| Days of hospitalization (median, IQR) | 6 (4–9) | 10.5 (3–6) | 5 (4–7) | <0.00001 |

IQR: interquartile range; CRP: C-reactive protein. The p-value with statistical significance is shown in italics.

Blood culture was performed on 83 patients, and only one yielded a positive result (S. pneumoniae). A sample of ear secretion was collected for culture in 43 episodes, and in 28, at least one microorganism was isolated: S. pyogenes (n=18), S. pneumoniae (n=2), Staphylococcus aureus (n=2), S. pneumoniae+Haemophilus influenzae (n=1), Streptococcus mitis (n=1), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n=1), Turicella otitidis (n=1), Achromobacter xylosoxidans (n=1), mixed microbiota with Finegoldia magna (n=1). S. pyogenes (n=3), S. pneumoniae (n=1), and H. influenzae (n=1) were also isolated from cultures from skin abscess/subperiosteal abscess.

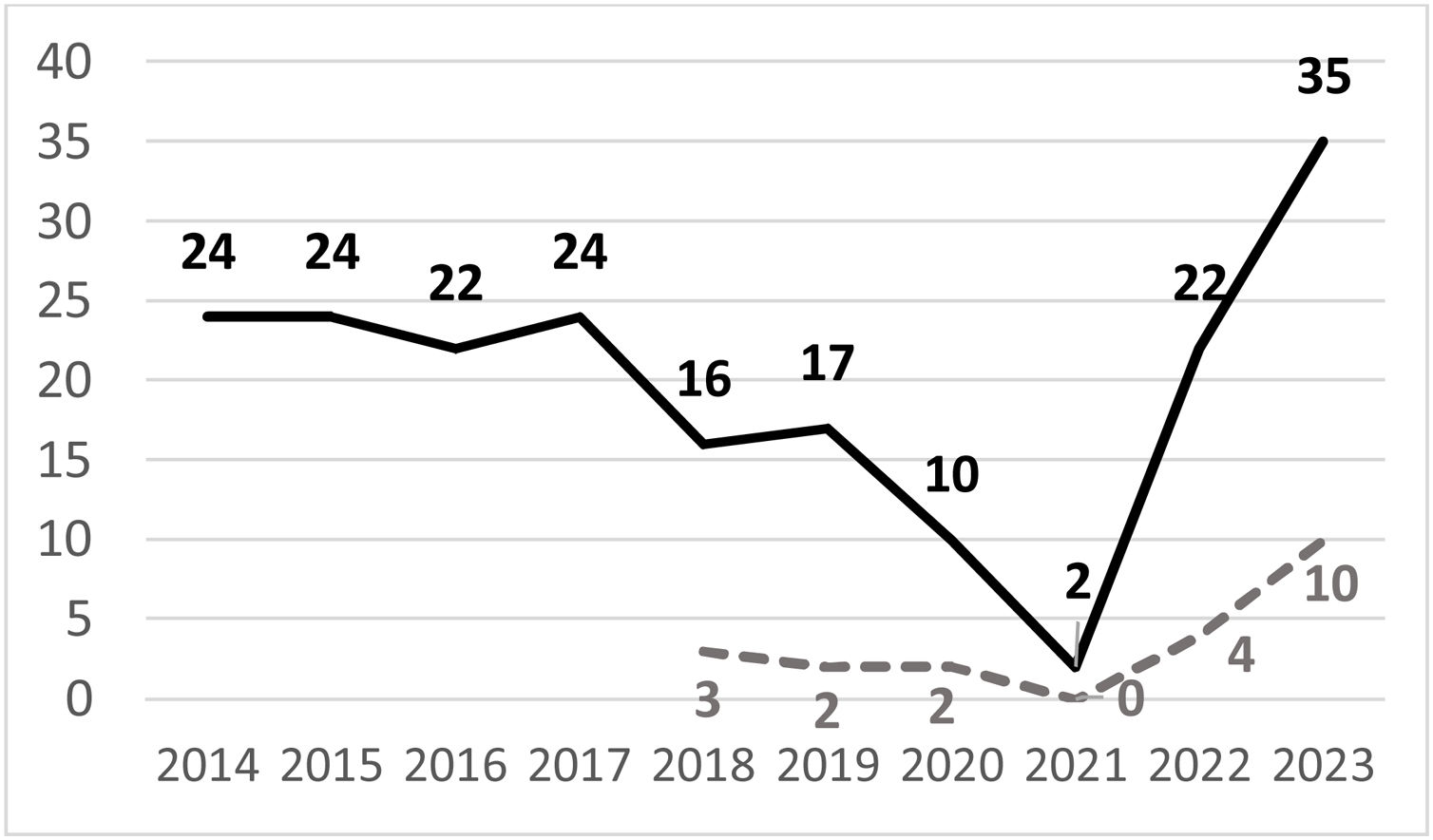

Fig. 1 shows the number of cases of acute mastoiditis per year.

A total of 26 cases (25.5%) underwent computed tomography (CT). Twenty-eight episodes (27.5%) developed complications, primarily subperiosteal abscess (Table 1A). Age, adequacy of vaccination schedule, previous history of AOM, cochlear implant possession, duration of symptoms and blood tests, leukocytes and C-reactive protein (CRP), were compared between patients with complications (n=28) and patients with no complications (n=74) (Table 1B). No significant differences were found, except for the duration of hospitalization, longer in patients with complications (median 10.5 days, versus 5 days; p<0.00001).

Only one patient was discharged home because of a very incipient mastoiditis. The rest of patients were hospitalized, and the median hospitalization duration was 6 days (IQR 4–9 days). All hospitalized patients received intravenous antibiotic treatment, and 26 episodes (25.5%) received corticosteroids. The most common antibiotic used was cefotaxime/ceftriaxone (n=76; 74.5%), followed by amoxicillin–clavulanate (n=6; 5.9%) and the combination of cefotaxime and clindamycin (n=6, 5.9%). Other antibiotics were administered in 13 episodes (12.7%).

Half of the episodes (n=52) underwent surgery. Myringotomy plus tympanostomy tube placement (TTP) was performed in 29 episodes (28.4%), myringotomy plus TTP plus drainage of abscess was performed in 12 cases (11.8%), mastoidectomy plus drainage of abscess plus TTP was performed in four patients (3.9%), mastoidectomy plus myringotomy plus TTP was performed in one (1%), mastoidectomy plus drainage of abscess in two (2%), and radical mastoidectomy was performed in one patient (1%). None of the patients died.

DiscussionThis study analyzes 102 episodes of acute mastoiditis in pediatric patients attended in a PED of a tertiary hospital in Spain, observing an increase of cases during the year 2023, with a relevant role of S. pyogenes.

Our study is consistent with the literature referred to clinical presentation.10 Symptoms were compared between patients younger and older than 2 years, without observing significant differences in the presence of fever, postauricular swelling, ear pain, duration of symptoms, blood tests, complications or days of hospitalization. However, differences were found referred to atrial protrusion and otorrhea (Table 1A).

Some authors have described a higher risk of mastoiditis or complications in children <2 years, absence of vaccination schedule, previous history of AOM or cochlear implant carriers.4,6,11 In our series, none of these variables showed statistically significant differences when comparing patients with and without complications. In fact, the finding of sigmoid sinus thrombosis was only found in four patients >2 years (p<0.05). Nor were differences observed when comparing these two groups in terms of duration of symptoms or analytical parameters, and we only observed a longer hospital stay in patients with complications (p<0.00001).

Regarding the reported increase of cases of acute mastoiditis, some aspects must be considered. In March 2020 the World Health Organization cataloged the situation caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus as an international pandemic,12 with the implementation of specific health measures. Until 2020 (pre-pandemic period) cases of acute mastoiditis in our center remained stable (range 16–24 cases per year) (Fig. 1). During the two COVID-19 pandemic years (2020–2021) we observed a marked decrease in cases (ten episodes in 2020 and two in 2021), and during the post-pandemic period we observed an increase in cases (especially during 2023). Global infections caused by any microorganism decreased significantly during the pandemic period due to social distancing and lockdown, which may explain the low incidence of mastoiditis. The subsequent increase in cases observed after the COVID-19 pandemic could be due to an increased susceptibility to infection after a period of social isolation, and could also be related to the marked increase in respiratory viral infections during 2022 and 2023. Likewise, the role of S. pyogenes is relevant. Since December 2022, several countries have published an alert on the increase of cases of group A Streptococcus infections in children.8,9 In the same line, our center reported a considerable increase in pediatric cases of S. pyogenes infections after the pandemic.13 Our results show a parallel increase in the cases of total mastoiditis and in the cases of mastoiditis with isolation of S. pyogenes in recent years. Other pathogens such as S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, H. influenzae, have been relegated to a secondary role. This differs from other previous publications, where S. pneumoniae is described as the main etiological agent, although these are from not-so-recent periods.6,10

Routine radiological imaging assessment is also controversial. Some authors propose to perform imaging tests in all suspected cases of mastoiditis,1 while most advocate reserve imaging tests for suspected complications.14 In our series, cranial CT was performed in 42 episodes (41%). Therapeutic management in terms of antibiotic therapy and surgery is similar to that reported in literature.10,11

Our study has limitations such as being retrospective and performed in a single center. Up to 30% of the patients had received antibiotic treatment prior to sample collection, which may justify this low rate of positive cultures. Nevertheless, the data analyzed reflects an increase in the number of cases in recent years. Prospective and multicenter studies are necessary in order to verify this rising trend.

In summary, this study shows an increase in the cases of acute mastoiditis during 2023. At least one microorganism was isolated in more than 30% of the episodes, mainly S. pyogenes. A younger age, personal history of previous AOM or cochlear implant, or analytical abnormalities were not associated with further complications. It is important to keep a close surveillance on this pathology.

Ethical approvalThe study has been assessed and approved by the center's Ethics and Research Committee.

FundingNo funding has been received to carry out this study and prepare the article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.