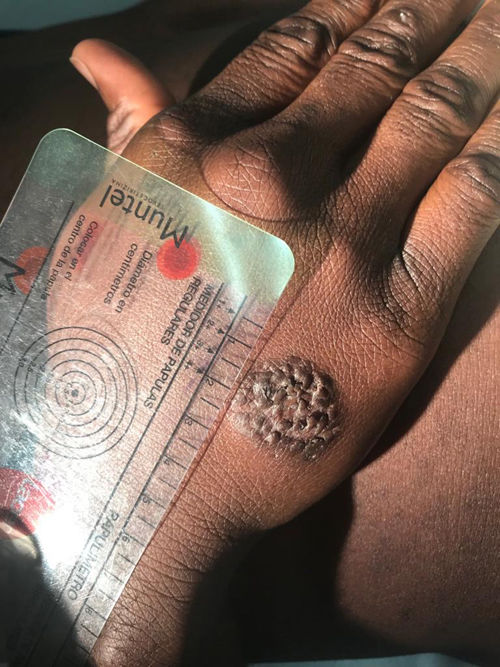

A 25-year-old man from Mali with a history of malaria and haematuria in childhood arrived in Spain in July 2018 with a total of 12 skin lesions on his chest and limbs. The lesions were papules and nodules ranging from 5 mm to 55 mm in diameter. Two of the lesions had an ulcerated centre and presented secretion suggestive of superinfection. The first lesion, located in the right pectoral area, appeared 3–4 months prior to the patient's arrival in Spain (between March and April 2018), when he was in Bamako (Mali). All other lesions gradually developed during his migration to Morocco. The patient denied having fever, asthenia, anorexia or other toxic symptoms, though he did report occasional pain in his ulcerated lesions. Physical examination revealed the patient to be afebrile and haemodynamically stable, with no cardiorespiratory, neurological or abdominal abnormalities, apart from the above-mentioned skin lesions (Figs. 1 and 2).

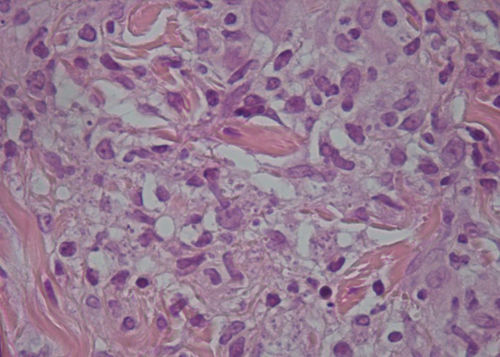

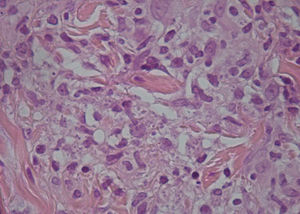

A microbiological culture was performed of the lesions with secretions, and a fine-needle aspiration biopsy (punch biopsy) was done of the peripheral area of several lesions. The culture showed colonies of Staphylococcus aureus, and the biopsy found the presence of amastigotes in the cytoplasm of the epithelioid cells (Fig. 3).

Punch of the lesion in Fig. 1. Intracellular amastigotes can be seen.

In addition, to complete the suspected diagnosis and immigrant patient study, the following were performed: blood test with haemogram, leukocyte formula, kidney function and liver profile (within normal limits); tuberculin skin test and QuantiFERON®-TB (both negative); human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), Strongyloides stercoralis and Schistosoma serologies (all negative); determination of immunoglobulins, proteinogram and lymphocyte subpopulations (all normal); 3 samples of faeces with Entamoeba dispar (negative polymerase chain reaction [PCR] for E. histolytica); and 3 urine samples (no evidence of parasites).

Given the suspected diagnosis, PCR of the sample from the previously performed biopsy was ordered. With the results pending, treatment was started with intramuscular meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime®) 20 mg/kg/day for 20 days plus 5 weekly sessions of intralesional antimoniate until the patient presented a total reduction of his lesions, which was achieved 6 months after starting treatment.

Closing remarksThe PCR result for the punch biopsy of the skin lesions was positive for Leishmania major.

This case offered an opportunity to review the differential diagnosis of multiple skin lesions in immunocompetent sub-Saharan patients.

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease endemic in Europe, Africa, Asia and South America1 caused by more than 20 species of parasite that are transmitted by the sand fly (Phlebotomus).2 It may present in various forms according to species and immune response: visceral (potentially fatal), cutaneous (most common) or mucocutaneous.3,4

In this case, it was disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis, as we found more than 10 lesions in different states in two or more parts of the body. This presentation is more typical in immunocompromised patients.5 Lesions are usually asymptomatic except in case of superinfection.

The suspected diagnosis is based on the patient's epidemiological and clinical context. The geographic distribution of the various subgenera of Leishmania and their most characteristic clinical presentation must be taken into consideration.

For diagnosis, biopsy (sensitivity 50%–70%) and PCR (sensitivity 97%) are preferred, since they are more effective than the Montenegro test (sensitivity 50%) and Novy-MacNeal-Nicolle (NNN) culture medium.3–5 To increase their sensitivity, samples must be taken from the affected area and the active border.

Systemic treatment is indicated in visceral forms, cutaneous forms with lesions measuring more than 4 cm or multiple lesions and/or facial or articular involvement. The first-line treatment option consists of parenteral pentavalent antimonials (Glucantime® 20 mg/kg/day for 20 days in cutaneous forms and 28 days in mucocutaneous and visceral forms). The most common possible adverse effects must be borne in mind. These include cardiac conduction disturbances, transaminitis, pancreatitis and kidney failure. There are other treatments, although they are less effective (miltefosine, ketoconazole, amphotericin B and pentamidine). Local treatment can be administered with paromomycin creams, intralesional antimonials or cryotherapy.4–6

Leishmaniasis is considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) to be one of the seven most significant tropical diseases in the world. In Spain, the disease is endemic.5

It is important to highlight the importance of applying a protocol in immigrant patients so as to rule out the most frequent diseases according to the area of origin.

Please cite this article as: Muelas-Fernandez M, Medina-Jerez F, Serra-Ramonet J, Flor-Perez A. Lesiones cutáneas en un mundo globalizado. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:151–152.