Subdural empyema (SE) is defined as a purulent collection between the duramater and arachnoid. The most common pathogenic mechanism is contiguous infection or cranial surgery, being extremely rare an spontaneous presentation,1,2 and the most common etiology is streptococci and staphylococci.3 We present a case of spontaneous SE by Escherichia coli, including a critical literature review.

A 69-year-old man debuted with 48h of 4/5 right hemiparesis and unsteady gait. He had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and dysuria, ten days before that was labeled as urinary tract infection (UTI) and treated with one dose of fosfomycin. Hemogram showed leukocytosis-neutrophils, elevated C-reactive protein (206mg/L). Unenhanced-CT showed a hypodense left frontoparietal subdural collection (30mm) and midline shift (10mm). On suspicion of chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH), two burr holes were performed, after durotomy, abundant purulent material was obtained, so we made a minicraniotomy to complete the evacuation. Empiric therapy was started with vancomycin (1g/8h), metronidazole (500mg/8h) and cefotaxime (2g/8h); Gram stain was identified Gram-negative bacilli, so vancomycin was suspended, continuing rest of therapy for 5 days until the arrival of culture. E. coli was isolated sensitive to cefotaxime, increasing dose to 2g/6h. The patient presented fever the sixth day, and a 14mm ring enhanced collection was found on the control CT, so a new surgical revision with larger craniotomy was done for evacuation of purulent, and increase of cefotaxim to 4.5g/6h (200mg/kg [90kg]) until 6 weeks. The patient improved until complete recovery, brain MRI after 27 days showed minimal collection. The urine and blood cultures were negative.

SE has a high mortality rate and is associated with severe neurological disabilities. The most common cause is meningitis in children and adjacent infections in adults.3–5 Neurological focal symptoms, leukocytosis and elevated inflammatory reactants are typical. CT and MRI show a subdural collection with contrast ring enhancement, and a restricted diffusion in the diffusion-weighted imaging.

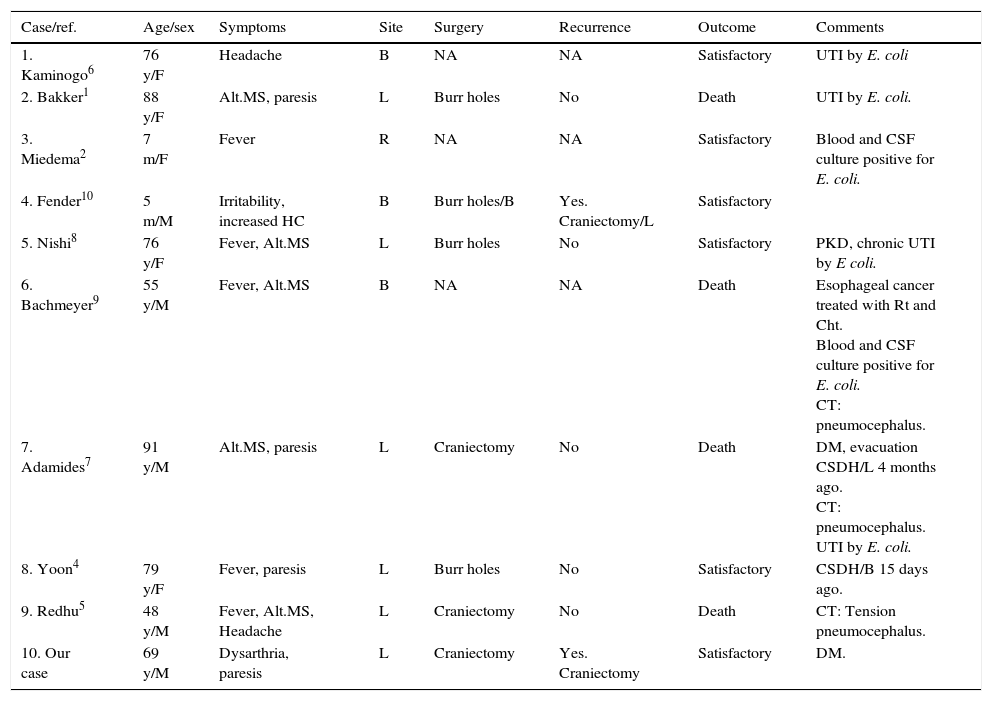

On extensive search in the literature, only 9 cases were found (Table 1): age ranged from 5 months to 91 years, no gender predilection. Six cases presented previous infections, four UTI1,6–8 and two meningitis.2,9 They had history of CSDH (20%) and diabetes mellitus (20%). The most common symptoms were altered mental status and fever (50% each), followed by paresis and headache. Pneumocephalus was observed in 30% at the moment of diagnosis and it has been associated with a worse prognosis.5,7,9 The surgical treatments were burr holes (40%) and craniotomy (30%). Two cases presented recurrences (minicraniotomy 1, burr hole 1), forcing an expanded craniotomy. The mortality was 40%.

Summary of previous cases of spontaneous SE by Escherichia coli.

| Case/ref. | Age/sex | Symptoms | Site | Surgery | Recurrence | Outcome | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Kaminogo6 | 76 y/F | Headache | B | NA | NA | Satisfactory | UTI by E. coli |

| 2. Bakker1 | 88 y/F | Alt.MS, paresis | L | Burr holes | No | Death | UTI by E. coli. |

| 3. Miedema2 | 7 m/F | Fever | R | NA | NA | Satisfactory | Blood and CSF culture positive for E. coli. |

| 4. Fender10 | 5 m/M | Irritability, increased HC | B | Burr holes/B | Yes. Craniectomy/L | Satisfactory | |

| 5. Nishi8 | 76 y/F | Fever, Alt.MS | L | Burr holes | No | Satisfactory | PKD, chronic UTI by E coli. |

| 6. Bachmeyer9 | 55 y/M | Fever, Alt.MS | B | NA | NA | Death | Esophageal cancer treated with Rt and Cht. Blood and CSF culture positive for E. coli. CT: pneumocephalus. |

| 7. Adamides7 | 91 y/M | Alt.MS, paresis | L | Craniectomy | No | Death | DM, evacuation CSDH/L 4 months ago. CT: pneumocephalus. UTI by E. coli. |

| 8. Yoon4 | 79 y/F | Fever, paresis | L | Burr holes | No | Satisfactory | CSDH/B 15 days ago. |

| 9. Redhu5 | 48 y/M | Fever, Alt.MS, Headache | L | Craniectomy | No | Death | CT: Tension pneumocephalus. |

| 10. Our case | 69 y/M | Dysarthria, paresis | L | Craniectomy | Yes. Craniectomy | Satisfactory | DM. |

Ref: reference; Sex: F: female, M: male; age: y: years, m: months; symptoms: Alt.MS: altered mental status, HC: head circumference; subdural empyema site: L: left, R: right B: bilateral; comments: UTI: urinary tract infection, PKD: polycystic kidney disease, DM: diabetes mellitus, Rt: radiotherapy, Cht: chemotherapy, CSDH: chronic subdural hematoma; NA: data not available.

Hematogenous spread seems to be the pathophysiological mechanism of spontaneous SE. In 40% of cases presented a distant infection with same germ.1,6–8 Other risk factors for overt infections could be previous CSDH,4,7 diabetes mellitus and immunosuppression states.7,9 In our case, we relate the genesis of spontaneous SE to hematogenous spread of an unconfirmed UTI, in association with diabetes mellitus.

The treatment of choice is surgical evacuation associated to culture adjusted intravenous antibiotics during 4–6 weeks.4,9 The most appropriate surgical approach is still under discussion, as some authors argue that the burr holes are sufficient for evacuation; others suggest that wider exposure as a craniotomy is more effective.3 Yilmaz et al.3 presented a lower recurrence rate on craniotomies (10%) vs. burr holes (38%). In cases with difficult pus extraction, as in multiloculated collections,4 parafalcine location3 and recurrences, is better to carry out a wide craniotomy. Both surgical techniques must perform thorough washing until clear liquid outlet, take care to remove the adherent material in the cortex for its lesion risk; placement of subdural drainage can be left up to 72h. In our case, the realization of minicraniotomy does not allow an extensive cavity wash, and the initial treatment with cefotaxime (2g/8h) was with low dose; these may favor the recurrence.

In conclusion, the spontaneous SE should be suspected in patients with fever and hypodense subdural collections in the head CT, and the administration of intravenous contrast may to increase its sensitivity. To achieve a favorable outcome must make an early surgery and begin antibiotic therapy. It seems that the craniotomy is associated with a lower relapse rate, however more studies are needed to confirm this fact.