Group A Streptococcus (GAS) causes mild diseases, and unfrequently invasive infections (iGAS). Following the December 2022 alert from the United Kingdom regarding the unusual increase in GAS and iGAS infections, we analyzed the incidence of GAS infections in 2018–2022 in our hospital.

MethodsWe conducted a retrospective study of patients seen in a pediatric emergency department (ED) diagnosed with streptococcal pharyngitis and scarlet fever and patients admitted for iGAS during last 5 years.

ResultsThe incidence of GAS infections was 6.43 and 12.38/1000 ED visits in 2018 and 2019, respectively. During the COVID-19 pandemic the figures were 5.33 and 2.14/1000 ED visits in 2020 and 2021, respectively, and increased to 10.2/1000 ED visits in 2022. The differences observed were not statistically significant (p=0.352).

ConclusionsIn our series, as in other countries, GAS infections decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and mild and severe cases increased considerably in 2022, but did not reach similar levels to those detected in other countries.

Streptococcus del grupo A (GAS) causa infecciones leves y ocasionalmente invasivas (iGAS). Tras la alerta publicada en diciembre de 2022 en el Reino Unido respecto al aumento de infecciones por GAS leves e iGAS, analizamos la incidencia de estas infecciones en 2018-2022 en nuestro hospital.

MétodosRealizamos un estudio retrospectivo de los niños atendidos en urgencias pediátricas (UP) diagnosticados de faringitis estreptocócica y escarlatina y los ingresados por iGAS durante 5 años.

ResultadosLa incidencia de infecciones por GAS fue de 6,43 y de 12,38/1.000 visitas a UP en 2018 y 2019, respectivamente. Durante la pandemia fue de 5,33 y de 2,14/1.000 visitas en 2020 y 2021, respectivamente, y aumentó a 10,2/1.000 visitas en 2022. Estas diferencias no fueron estadísticamente significativas (p=0,352).

DiscusiónEn nuestra serie, al igual que en otros países, las infecciones por GAS disminuyeron durante la pandemia de COVID-19, pero en 2022 aumentaron considerablemente los casos leves y graves, sin alcanzar cifras similares a las detectadas en otros países.

Group A Streptococcus (GAS), also called Streptococcus pyogenes, causes mild diseases such as tonsillopharyngitis and scarlet fever and is the most common cause of bacterial pharyngitis in adolescents and children. In temperate climates, the incidence of GAS pharyngitis peaks during winter and early spring.1 However, unfrequently, GAS can lead to invasive infection (iGAS), defined as illness associated with detection of GAS in a normally sterile site (blood, pleural fluid, joint fluid, CSF, deep tissue) or from a nonsterile site obtained from a patient with toxic shock syndrome. iGAS can present as different clinical syndromes, including bacteremia without focus, pneumonia, and cellulitis, and severe manifestations, including necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS).2

On December 2nd 2022, an alert was published in the United Kingdom regarding the unusual increase in Streptococcus pyogenes infections (tonsillitis and scarlet fever mainly) and simultaneously of iGAS infections. A relevant number of deaths were reported in a short period of time in children under 10 years old.3 Other countries in Europe have also reported similar concerns of increased group A streptococcal infections.4

In this epidemiological context, we have analyzed the incidence of pharyngitis, scarlet fever, and iGAS diseases in children admitted to the emergency department (ED), in a tertiary hospital in Madrid, Spain.

MethodsThis is a retrospective study performed over a period of 5 years (from January 2018 to December 2022). Demographic and clinical data of the children were obtained from the electronic medical record system. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Clinical Research from the University Hospital La Paz, Madrid, Spain (PI-4781).

Cases of streptococcal pharyngitis or scarlet fever with detection of S. pyogenes in the pharynx by throat culture or rapid antigen test (OSOM Strep A Test) who met the McIsaac criteria were included.5 The existing protocols upon admission in our hospital include PCR screening for respiratory syncytial virus and influenza viruses. During the pandemic and post-pandemic years (2020–2022), SARS-CoV-2 antigen testing was frequently performed following the established protocols.

The following diagnoses were considered iGAS when S. pyogenes was isolated in a sterile sample (blood, pleural fluid, CSF, joint fluid, abscess): pneumonia, meningitis, necrotizing fasciitis, osteoarticular infection, deep abscess (including orbital cellulitis, pharyngeal and parapharyngeal abscesses), sepsis and toxic shock. Cases of clinical toxic shock in which the isolation of S. pyogenes was from a non-sterile site (throat, sputum, vagina, skin lesion) were also included. Sepsis was considered when GAS was isolated in blood and a change in Pediatric-SOFA score ≥2 was targeted.6

The results are presented as absolute frequencies and/or percentages; the quantitative data are expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test and continuous variables were compared with non-parametric tests. p values under 0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistic Version 21, IBM Inc., Chicago, IL).

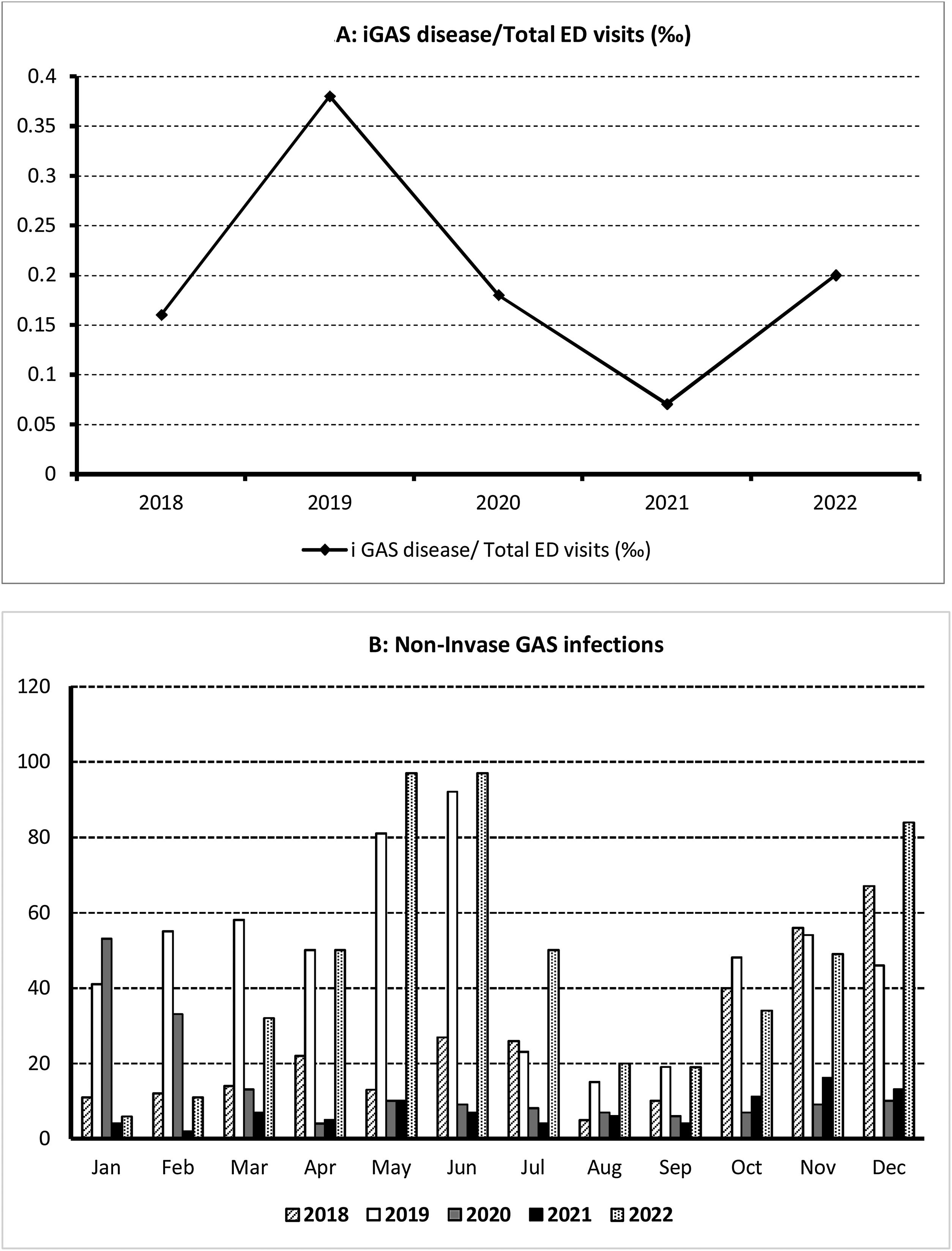

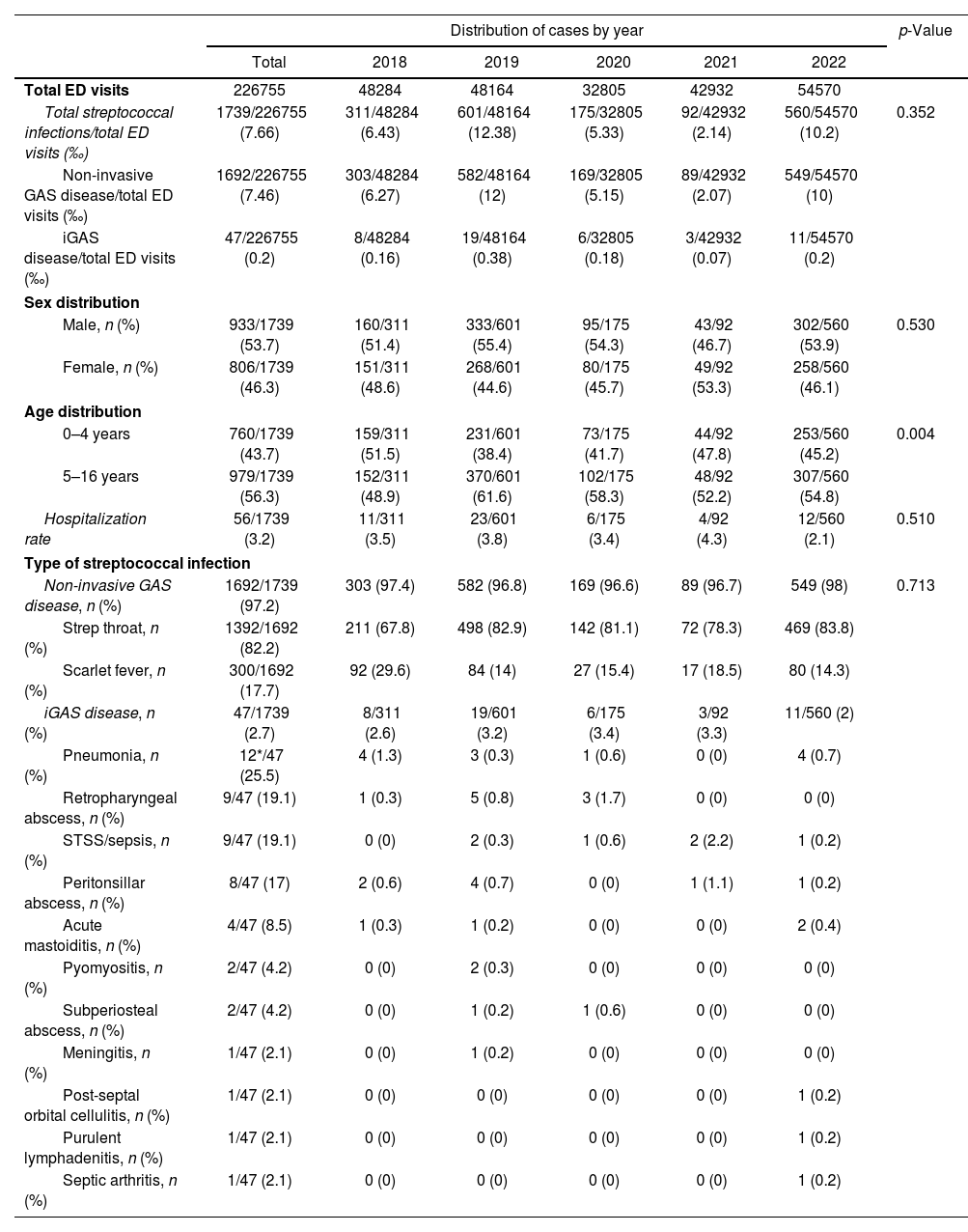

ResultsDuring the study period consisting of two pre-pandemic years 2018–2019, two years during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021) and the first post-pandemic year (2022), 226,755 children were attended in our ED, of whom 1739 were diagnosed of GAS infections, 1692 (97.3%) with scarlet fever and streptococcal throat and 47 (2.7%) of iGAS. The median age was 5.3 years (IQR: 3.8–7.9); 53.7% of all affected children were male and 46.3% female. The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. iGAS incidence and monthly distribution is shown in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of the patients with Streptococcus pyogenes infections.

| Distribution of cases by year | p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

| Total ED visits | 226755 | 48284 | 48164 | 32805 | 42932 | 54570 | |

| Total streptococcal infections/total ED visits (‰) | 1739/226755 (7.66) | 311/48284 (6.43) | 601/48164 (12.38) | 175/32805 (5.33) | 92/42932 (2.14) | 560/54570 (10.2) | 0.352 |

| Non-invasive GAS disease/total ED visits (‰) | 1692/226755 (7.46) | 303/48284 (6.27) | 582/48164 (12) | 169/32805 (5.15) | 89/42932 (2.07) | 549/54570 (10) | |

| iGAS disease/total ED visits (‰) | 47/226755 (0.2) | 8/48284 (0.16) | 19/48164 (0.38) | 6/32805 (0.18) | 3/42932 (0.07) | 11/54570 (0.2) | |

| Sex distribution | |||||||

| Male, n (%) | 933/1739 (53.7) | 160/311 (51.4) | 333/601 (55.4) | 95/175 (54.3) | 43/92 (46.7) | 302/560 (53.9) | 0.530 |

| Female, n (%) | 806/1739 (46.3) | 151/311 (48.6) | 268/601 (44.6) | 80/175 (45.7) | 49/92 (53.3) | 258/560 (46.1) | |

| Age distribution | |||||||

| 0–4 years | 760/1739 (43.7) | 159/311 (51.5) | 231/601 (38.4) | 73/175 (41.7) | 44/92 (47.8) | 253/560 (45.2) | 0.004 |

| 5–16 years | 979/1739 (56.3) | 152/311 (48.9) | 370/601 (61.6) | 102/175 (58.3) | 48/92 (52.2) | 307/560 (54.8) | |

| Hospitalization rate | 56/1739 (3.2) | 11/311 (3.5) | 23/601 (3.8) | 6/175 (3.4) | 4/92 (4.3) | 12/560 (2.1) | 0.510 |

| Type of streptococcal infection | |||||||

| Non-invasive GAS disease, n (%) | 1692/1739 (97.2) | 303 (97.4) | 582 (96.8) | 169 (96.6) | 89 (96.7) | 549 (98) | 0.713 |

| Strep throat, n (%) | 1392/1692 (82.2) | 211 (67.8) | 498 (82.9) | 142 (81.1) | 72 (78.3) | 469 (83.8) | |

| Scarlet fever, n (%) | 300/1692 (17.7) | 92 (29.6) | 84 (14) | 27 (15.4) | 17 (18.5) | 80 (14.3) | |

| iGAS disease, n (%) | 47/1739 (2.7) | 8/311 (2.6) | 19/601 (3.2) | 6/175 (3.4) | 3/92 (3.3) | 11/560 (2) | |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 12*/47 (25.5) | 4 (1.3) | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.7) | |

| Retropharyngeal abscess, n (%) | 9/47 (19.1) | 1 (0.3) | 5 (0.8) | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| STSS/sepsis, n (%) | 9/47 (19.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (2.2) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Peritonsillar abscess, n (%) | 8/47 (17) | 2 (0.6) | 4 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Acute mastoiditis, n (%) | 4/47 (8.5) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.4) | |

| Pyomyositis, n (%) | 2/47 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Subperiosteal abscess, n (%) | 2/47 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Meningitis, n (%) | 1/47 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Post-septal orbital cellulitis, n (%) | 1/47 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Purulent lymphadenitis, n (%) | 1/47 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Septic arthritis, n (%) | 1/47 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | |

ED: emergency department; iGAS: invasive group A Streptococcus disease; STSS: streptococcal toxic shock syndrome.

The incidence of GAS infections in the two pre-pandemic years analyzed were 6.43/1000 ED visits (2018) and 12.38/1000 ED visits (2019). During the 2 pandemic years (2020 and 2021), we observed a decrease in the incidence to 5.33/1000 and 2.14/1000 ED visits respectively; which increased during the first post-pandemic year (10.2/1000 ED visits). The differences observed were not statistically significant (p=0.352). The incidence of iGAS followed a parallel course to mild infections, with a minimum in 2021 (0.07/1000 ED visits) returning in 2022 to the pre-pandemic figures detected in 2019, but not higher. The percentage of GAS infections among patients aged 5–16 years was significantly higher during 2019. The hospitalization rate was 3.2%, and we did not observe significant differences between the 5 years analyzed (p=0.510).

The most common iGAS infections were pneumonia (25.5%), retropharyngeal abscess (19.1%), streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS)/sepsis (19.1%), peritonsillar abscess (17%), acute mastoiditis (8.5%), pyomyositis (4.2%), subperiosteal abscess (4.2%), meningitis (2.1%), post-septal orbital cellulitis (2.1%), purulent lymphadenitis (2.1%), and septic arthritis (2.1%). Three patients diagnosed with pneumonia resulted in STSS, two of them during the pre-pandemic period. No significant differences were observed in the percentage of iGAS cases among the 5 years analyzed (p=0.713). Respiratory coinfections were detected in 8/47 (17%) patients with iGAS, 5 were in the pre-pandemic years and 3 in the post-pandemic years. Influenza A was isolated in 5 cases, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in 2 cases and rhinovirus, SARS-CoV-2 and influenza simultaneously in 1 case. All invasive infections received empirical treatment with third-generation cephalosporins or penicillin usually associated with clindamycin (which was maintained after confirmation). In our series we did not have any deaths.

DiscussionIn this study we analyzed the evolution of GAS infections during the last 5 years in a large hospital in Spain. Mild and invasive GAS infections decreased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic period. During 2022, first post-pandemic year, we have seen a noticeable increase of cases, but it has not exceeded the incidence found in 2019, the year with the highest number of cases.

Rates of GAS infections have gradually declined during the 20th century due to improved living conditions and access to antibiotics. However, changes in host susceptibility to infection and genetic changes in circulating GAS strains can lead to increases in specific disease rates. In the late 1980s, a marked increase in the number of iGAS infections was observed in Europe and in the U.S. Although this initial peak is thought to be associated with the emergence of more virulent strains (e.g., M1T1), multiple emm types have been found to comprise iGAS infections in industrialized societies.7 In Madrid, Gonzalez-Abad et al. described an increase in the incidence of iGAS infections between 2011 and 2018, with emm1 and emm3 types being the most commonly isolated and associated with pneumonia and deep soft tissue infections8 and Villalón et al. analyzed the microbiological characteristics of iGAS isolated in Spain between 2007 and 2019, highlighting that emm1, emm3, emm4 and emm6 were mostly associated with respiratory infections in children.9 In our study we have not determined the emm types, so we do not know if they have changed over the period of study.

Since the United Kingdom published the alert on the increase of GAS infections in children at the beginning of December 2022,3 other countries in Europe (France, Ireland, The Netherlands, and Sweden),10 and in North America (USA) have joined in.11 The alert reported an increase not only in mild infections such as pharyngitis and scarlet fever, but also in invasive infections. One theory for this increase, although debated, is that the social isolation that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in reduced exposure to GAS and, therefore, young children lacked immunity to these bacteria, increasing their susceptibility.3 This could explain the significantly higher age of affected children in 2019 compared to 2022. In addition, an early start of the GAS infection season coinciding with a high circulation of respiratory viruses (influenza and RSV) and possible viral coinfection may increase the risk of invasive GAS disease. Other authors suggest that the reason for this rise in children's infections is due to immune system damage caused by SARS-CoV-2 infections.12

In our study, we analyzed the incidence of streptococcal pharyngitis and scarlet fever in the emergency department, and iGAS cases admitted to a large teaching hospital in Madrid in three periods: pre-pandemic (2018–2019), COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021) and post-pandemic (2022). We found no significant differences in the incidence of GAS pharyngotonsillitis and scarlet fever during the pre- and post-pandemic periods as described by other authors.

During the COVID-19 pandemic years (2020–2021), infections caused by GAS, like other non-COVID infectious diseases, decreased significantly due to social distancing and lockdown. Therefore, in our series, mild GAS infections and iGAS infections decreased significantly during the pandemic period, and in 2022 we have observed a reemergence of GAS infections reaching the pre-pandemic levels, but not higher as described in the United Kingdom alert.

Although mortality is well described, especially in the most severe cases (septic shock and necrotizing fasciitis), which can reach 1–2% of iGAS cases, no deaths were recorded in our series.

Our study has limitations such as being retrospective and performed in a single-center. Nevertheless, it is a large hospital, the methodology has been homogeneous throughout the study period and the relationship between mild and severe infections has been taken into account. In addition, it is possible that we identified the onset of an increase in cases in the months following our study and that we were unable to detect them since in this study we only included cases up to December 2022. Prospective and multicenter studies in different regions are necessary in order to analyze the incidence of GAS infections in our country.

In summary, in our series as in other countries, GAS infections decreased markedly during the COVID-19 pandemic, but in 2022 there has been a considerable increase in both mild and severe cases, but did not reach figures similar to the levels detected in other European countries. It is important to keep a close surveillance on S. pyogenes infections in the coming months to confirm this trend.

FundingNo funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rosario López López MD, PhD, Marta Bueno-Barriocanal MD, José A. Ruiz Domínguez MD, PhD, Begoña de Miguel MD, PhD