On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organisation declared a pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) due to coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. The virus has spread to over 180 countries, with 2,815,347 confirmed cases and 197,516 deaths.1

It is known that the spectrum of disease severity is broad, with many patients (80%) who are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic (fever, cough and asthenia), and that the disease's mortality rate may be less than 1%.2 Treatment is symptomatic, as these cases have a self-limiting course of 1-2 weeks, and isolation at home is recommended.3

There is growing evidence on radiological findings in the disease caused by coronavirus (COVID-19). A chest X-ray offers little sensitivity for detecting abnormalities (absent in over 40% of patients).2 Computed tomography (CT) of the chest is more sensitive, but has multiple disadvantages: the associated exposure to ionising radiation in mild disease; issues of availability and resource rationing; the patient's haemodynamic instability for transfer; and the risk of transmission of the infection, among other disadvantages, may eclipse the technique's potential benefits.

There is currently no evidence on the usefulness of thoracic ultrasound when monitoring the disease. The aim of this case series is to report the sequential thoracic ultrasound findings in 3 patients with mild COVID-19, from onset of symptoms up to complete resolution on ultrasound.

We report the cases of a 35-year-old man (patient 1), a 35-year-old woman (patient 2) and a 45-year-old woman (patient 3) who visited the emergency department with a dry cough, asthenia and low-grade fever. Physical examination was normal, and all 3 had positive reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) tests of nasopharyngeal exudate.

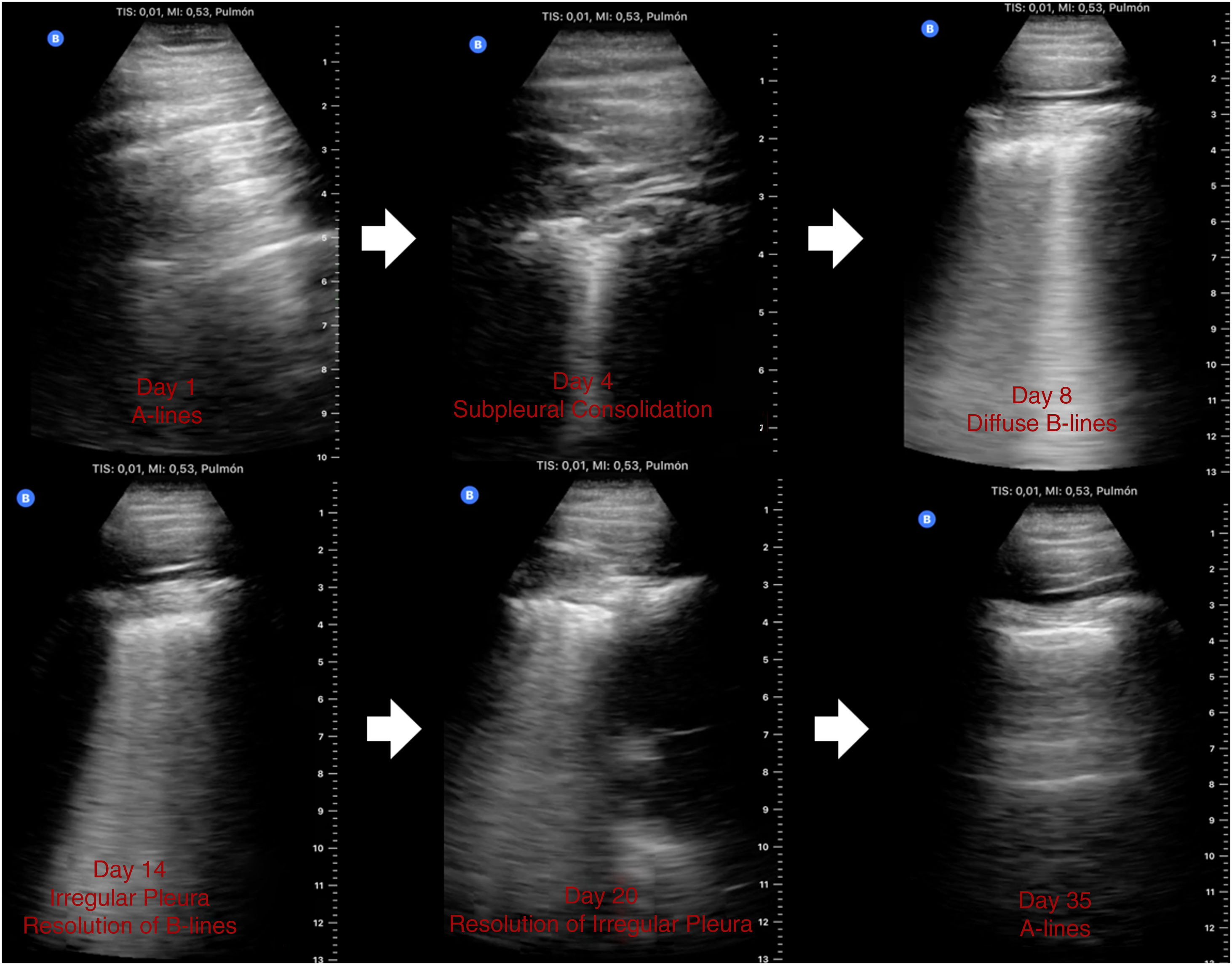

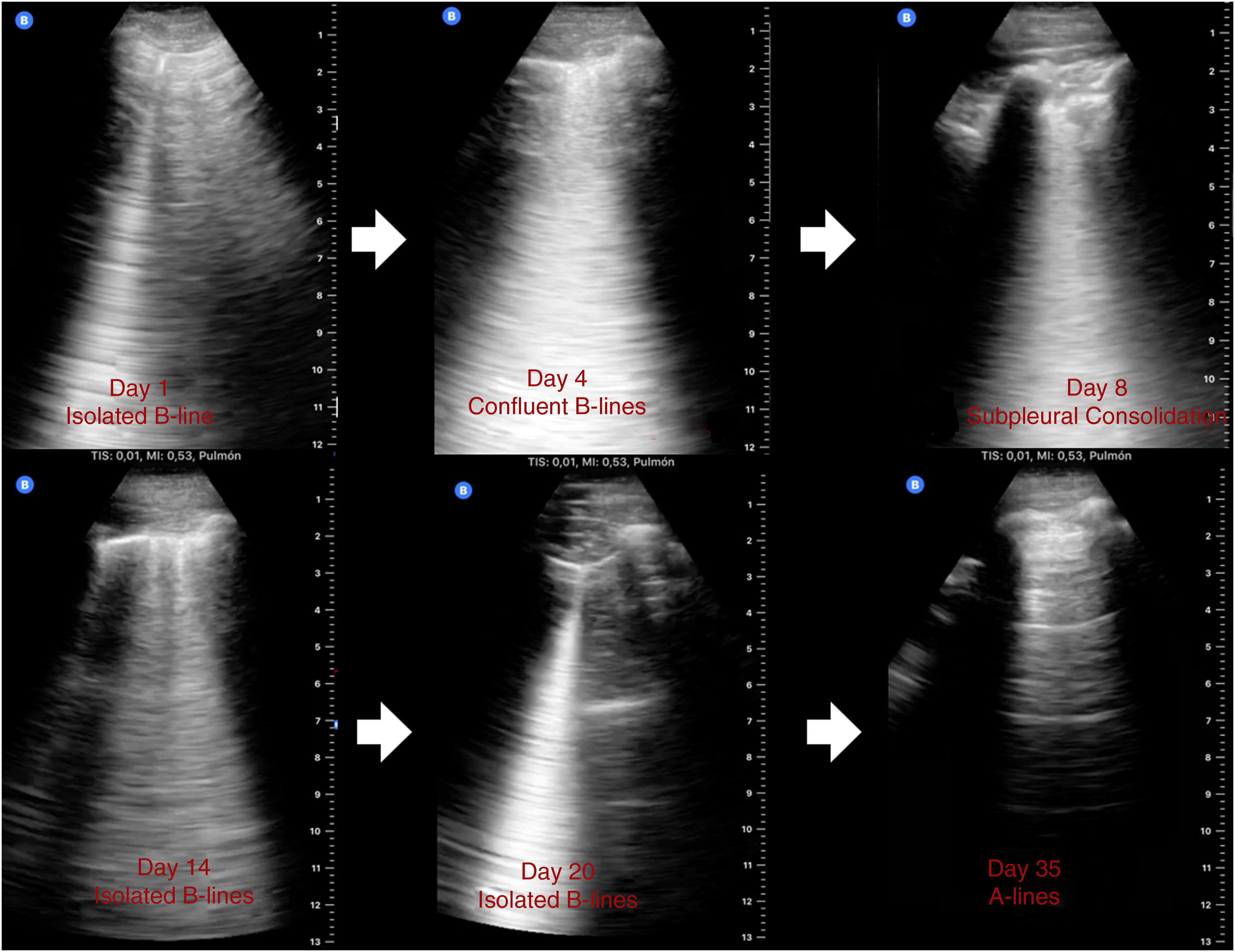

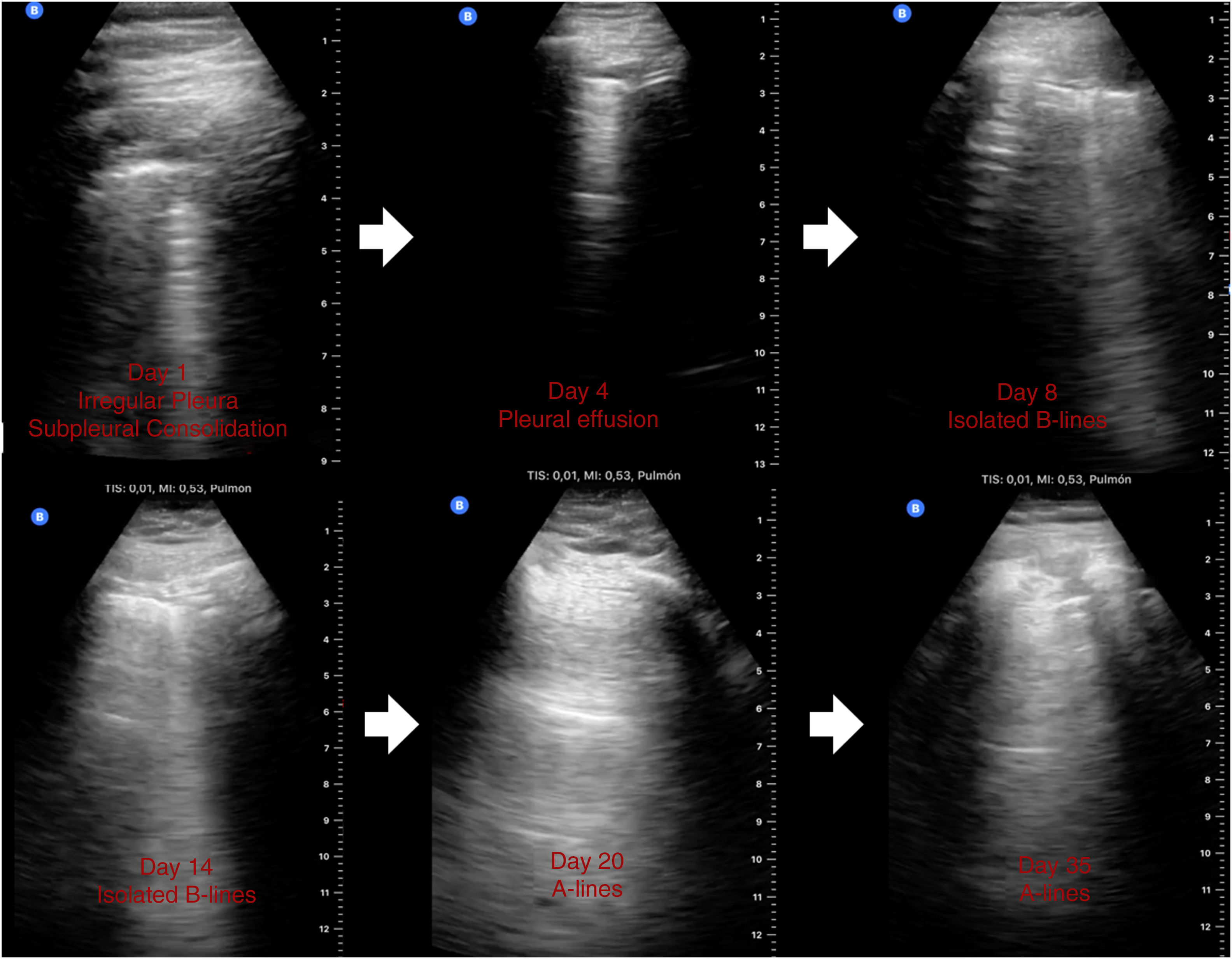

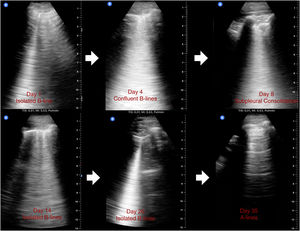

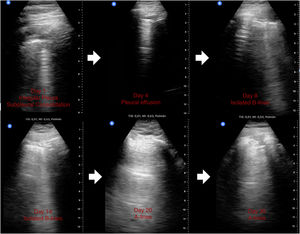

A thoracic ultrasound that schematically examined the anterior, lateral and posterior areas bilaterally using a pocket-sized device (Butterfly IQ) showed an A-line pattern (patient 1, Fig. 1), isolated B-line (patient 2, Fig. 2), irregular pleura and subpleural consolidation (patient 3, Fig. 3), all on the posterior bases. All 3 patients were discharged from hospital with symptomatic treatment and hydroxychloroquine (2 patients) and had daily follow-up ultrasounds (Figs. 1–3). In the days that followed, progression towards larger numbers of isolated, confluent B-lines; pleural effusion; and subpleural consolidations (at the most symptomatic time) were seen. While signs and symptoms were resolving, the thoracic ultrasound showed the progressive replacement of consolidations with isolated B-lines, and finally the reappearance of normal A-lines (asymptomatic), though this happened on different days in each patient. Resolution of symptoms occurred between day 14 and day 21, though with patients 1 and 2, signs and symptoms of dyspnoea and asthenia on exertion persisted until practically day 35.

There is growing evidence for the use of imaging techniques in the management of COVID-19. A previous study of 1,049 patients who had RT–PCR and CT scans found CT to be more sensitive to abnormalities (59 versus 88%, respectively).4 This would suggest that CT should be considered as a detection tool, particularly in epidemic areas. Another study in 21 patients with pneumonia caused by uncomplicated COVID-195 found that performing CT scans every 4 days enabled physicians to determine that radiological findings peaked on approximately day 10, and resolution was very gradual, persisting beyond day 26, when a follow-up CT scan was performed.

Subpleural consolidations, pleural irregularity and B-lines in the context of this pandemic may suggest lung infection caused by COVID-19. As exemplified in the 3 cases reported, it is possible to correlate thoracic ultrasound findings to symptoms and their resolution, which in 2 of the cases this did not happen until the fifth week, when A-lines (normal aeration pattern) were seen to reappear. This accounts for some of the residual symptoms that many patients report after discharge and avoids other, more invasive complementary tests.

To date, thoracic ultrasound and CT have been used for the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with COVID-19, particularly in patients with residual symptoms; however, these resources may not be available everywhere or their use may be contraindicated. Hence, alternative methods must be considered.

Thoracic ultrasound is harmless and may be completed quickly by following simple, easily applied protocols. Currently there is a wide range of available portable, pocket-sized ultrasound devices which allow studies to be performed on asymptomatic and unstable patients, either in their homes or in a hospital setting. Although there is ongoing debate about how it should be applied, there is a general consensus on its usefulness.6

The main limitation of thoracic ultrasound is its low specificity, meaning its findings can be similar to findings in different diseases. However, in the current pandemic, detection of these findings may be highly suggestive of COVID-19 infection.

In conclusion, it is worthwhile to consider using thoracic ultrasound in follow-up until complete resolution of symptoms.

Declaramos que no existe financiación externa ni conflicto de intereses por parte de los autores.

Please cite this article as: Tung-Chen Y, Marín-Baselga R, Soriano-Arroyo R, Muñoz-del Val E. Cambios evolutivos pulmonares en la ecografía torácica en pacientes con COVID-19. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:46–48.