A previously healthy 53-year-old woman presented with a one-week history of progressive right-sided weakness and diplopia. Upon interrogation, she referred episodes of headache, nausea, and fever up to 39°C for the past three weeks. At admission, her vital signs were within normal limits. Neurological examination was relevant for bilateral vertical gaze palsy without nystagmus or other cranial nerve palsies, right-sided hemiparesis, and left-sided cerebellar syndrome. There were no signs of meningeal irritation, and the rest of the examination was unremarkable.

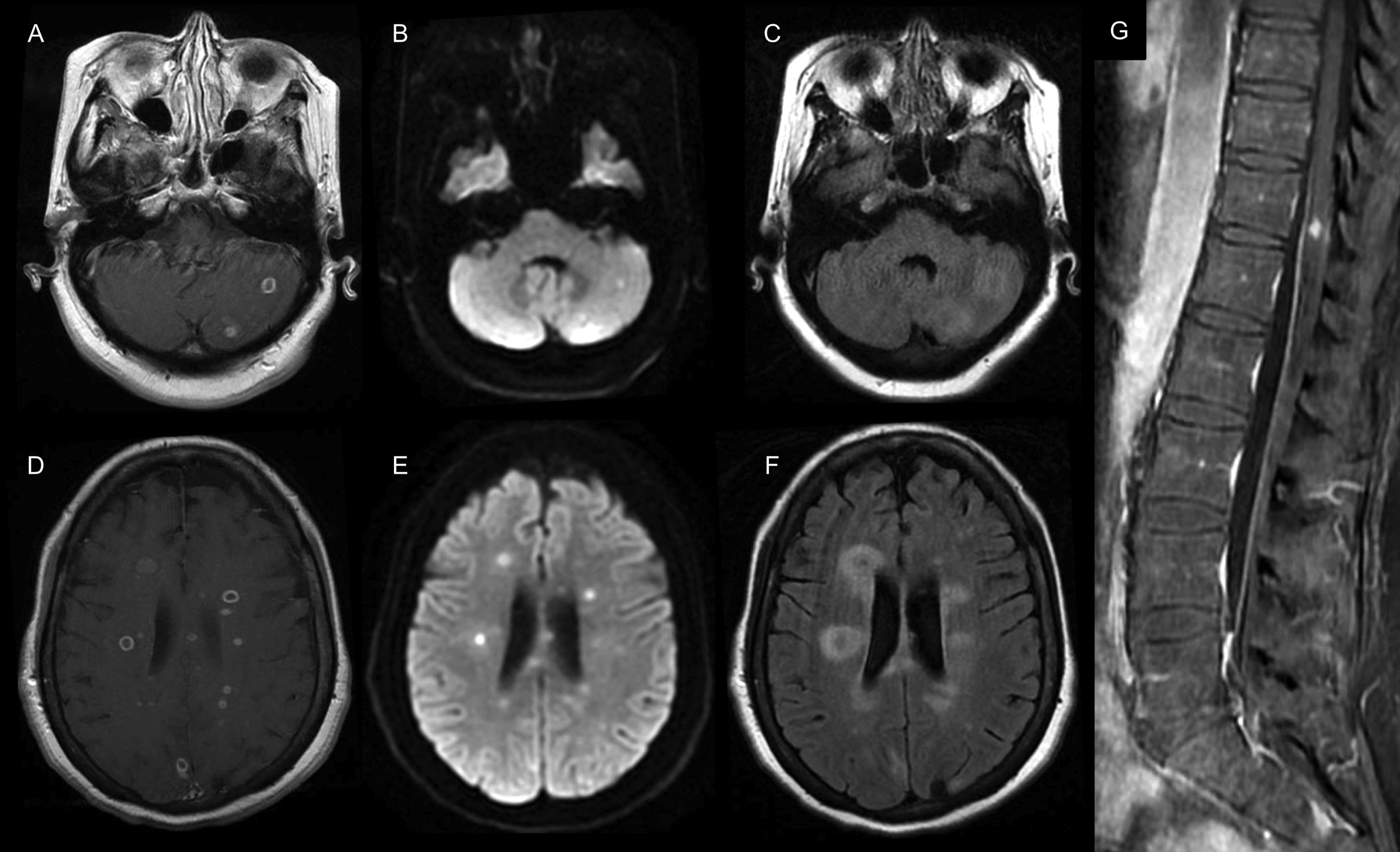

Routine blood workup was relevant for an elevated C-reactive protein in 1.68mg/dL (range: 0–1), the rest of the workup, including a full blood count, serum electrolytes, renal and liver function tests were within normal ranges. Serum testing for syphilis, hepatitis C and HIV were negative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed multiple infra and supratentorial abscesses in different stages (Fig. 1A–F). The cerebrospinal fluid analysis (CSF) showed elevated proteins in 121mg/dL (range: 10–45), pleocytosis with 30cells/mm3 (range: 0–10) of which 70% were polymorphonuclear a normal glucose (60mg/dL [range: 50–80]) and CSF/serum glucose ratio (0.7), with negative Gram and acid-fast bacilli stains as well as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for Toxoplasma gondii, nucleic acid amplification for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and serum cryptococcal antigen. With those results, we started treatment with ceftriaxone, vancomycin, and metronidazole. To determine the abscesses source, we performed a dental exam and a transesophageal echocardiogram with unremarkable results; lastly, a whole-body computed tomography (CT) revealed multiple liver abscesses.

Brain and spine MRI. (A, D) Axial T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI shows multiple infra and supratentorial ring-enhancing lesions that were hyperintense on the (B, E) diffusion-weighted image (DWI) sequence with perilesional edema seen on the (C, F) fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence. (G) Coronal T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI of the spine shows a contrast-enhancing lesion of the central spinal cord.

Three days after admission, she developed acute urinary retention, and an MRI of the spine revealed a central spinal cord abscess at the twelfth thoracic vertebra (Fig. 1G). On day eight, a rapidly-growing mycobacterium (RGM), typified as Mycobacterium mucogenicum by PCR amplification with the GenoType Mycobacterium AS (additional species) probe assay (Hain Lifescience, GmbH, Nehren, Germany) resistant to levofloxacin and susceptible to amikacin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, azithromycin, clarithromycin, moxifloxacin, and linezolid was isolated from the CSF. We adjusted treatment to IV amikacin, linezolid, and azithromycin for four weeks. Neurological symptoms gradually improved. After excluding primary immune deficiencies, we discharged her five weeks after admission on oral azithromycin, moxifloxacin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Six months after discharge, neurological symptoms resolved as well as the MRI lesions leading to stopping antibiotics. On follow-up one year after being diagnosed, the patient remains asymptomatic.

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are classified by their growth rate as slow-growing or RGM, which refers to the ability of some NTM to grow into mature colonies in less than seven days.1Mycobacterium mucogenicum is a ubiquitous environmental RGM usually isolated from in-hospital medical devices, city water supplies, and contaminated food. Its isolation requires careful microbiological handling and analysis of the sample because it can be easily contaminated.1,2 Therefore, diagnosing a suspected infection by this pathogen requires careful assessment of its clinical significance.3

Symptomatic infections by Mycobacterium mucogenicum are mostly catheter-related bloodstream infections in hemodialysis patients. The source inoculation in immunocompetent patients remains incompletely understood.2,3 In a series analyzing surgically-resected gastrointestinal specimens from 11 patients with Crohn's disease, Mycobacterium mucogenicum was identified by PCR in one patient.4 Also, in an autopsy study of an immunocompetent patient, it showed to have caused granulomatous hepatitis.5 These findings could lead to the hypothesis that the gastrointestinal system is a potential source of entry. In our patient, the finding of a liver abscess suggests that the digestive tract was the primary source of infection.

Currently, there are only three reported cases of central nervous system (CNS) infections. The first case involves a patient with AIDS who presented with meningitis; the only reported clinical data was a lumbar puncture performed for an unrelated reason three weeks before symptoms onset.6 The second was in a non-immunocompromised 23-year-old man who presented with a three-week history of fever, meningeal signs, and elevated CSF cells in 23cells/mm3 (26% polymorphonuclear); the patient died three days after admission. The third case was in an 82-year-old man with a permanent pacemaker, diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and a femoral vascular graft, who presented with fever and confusion. CSF analysis was relevant for elevated proteins in 670mg/dL, and his brain CT showed extensive cerebral thrombophlebitis; this patient died from multiple organ failure six days after admission.7 In all cases, Mycobacterium mucogenicum was isolated from the CSF.

Treatment of CNS infections by Mycobacterium mucogenicum should be based on the experience acquired from severe infections in extra-neural sites, including a combination of IV antibiotics (aminoglycosides with a macrolide and a quinolone) for at least 2–4 weeks, followed at least six months of oral antibiotics, guided by clinical and microbiological responses.1,2 For these patients, we suggest adding follow-up neuroimaging studies. It is essential to recognize this treatable pathogen in patients who present with multiple CNS abscesses and an initial negative workup.

Informed consentInformed consent for publication was obtained from the patient.

Source of fundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.