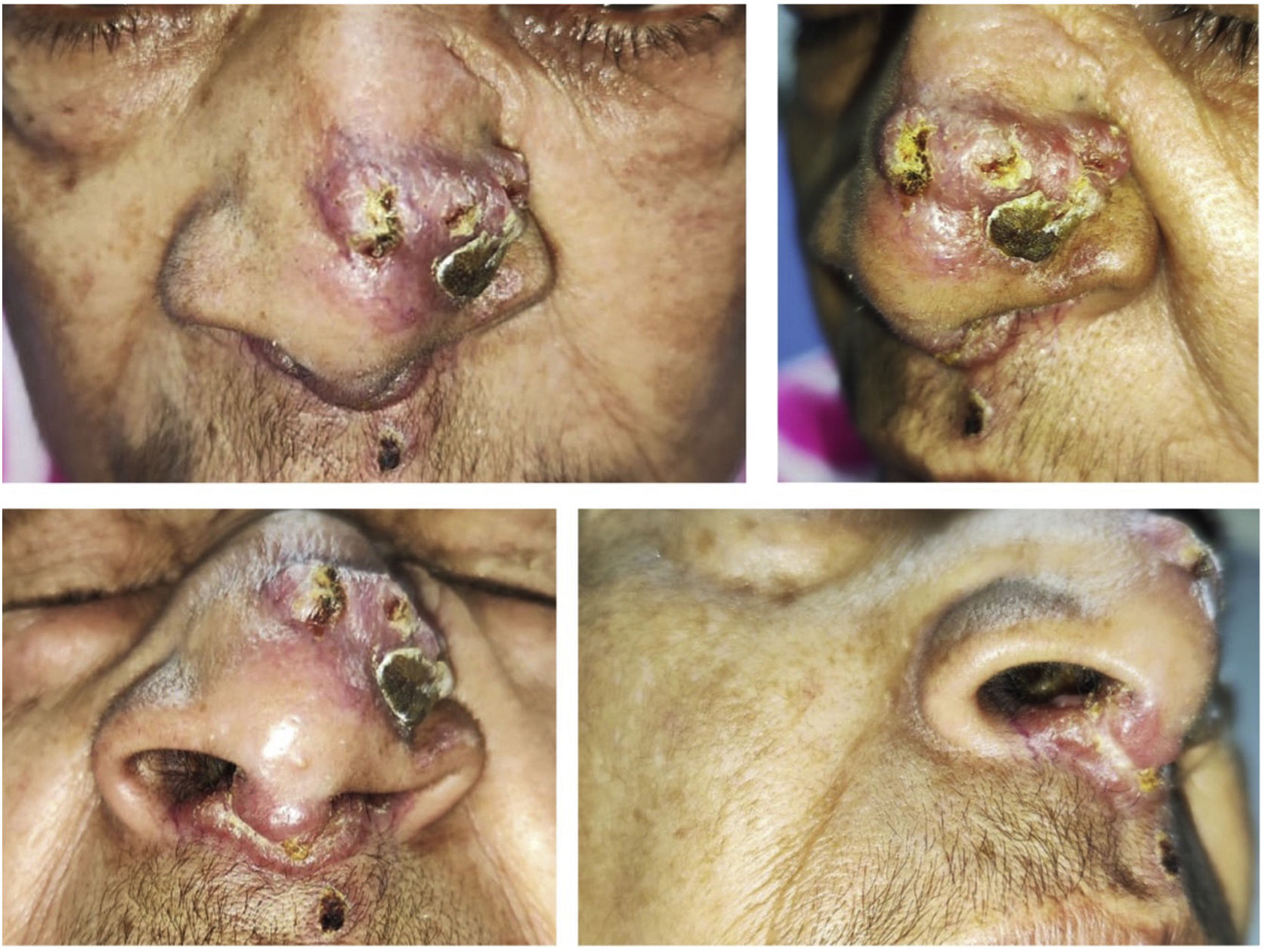

This was a 63-year-old woman from a rural area of Colombia who consulted for lesions on the bridge of her nose and nasal mucosa. The patient reported a 10-year history of nasal and sinus symptoms, and in 2016 she noticed the development of lesions in the nasal mucosa on the right side which progressed, generating obstruction. Subsequently, she began to develop erythematous lesions on the bridge of her nose. She was assessed by Ear, Nose and Throat, where they performed multiple surgical procedures (including maxillectomy and turbinectomy) with biopsies of the nasal mucosa taken for histopathology and microbiology, the results of which were inconclusive. Finally, the patient required hospital management to clarify the diagnosis. While in hospital she was assessed by dermatology. A friable, erythematous plaque was observed, with a friable, smooth, ulcerated surface, on the left lateral aspect of the nasal dorsum; infiltration and thickening of the septal nasal mucosa was also identified (Fig. 1). Given the presence of infiltrating lesions in the central facial region, skin biopsies were taken for microbiology (direct examinations and cultures for aerobes, anaerobes, mycobacteria and fungi), histopathology and molecular studies (PCR for Leishmania spp. and universal panel of mycosis) to rule out different aetiologies associated with a midline destructive syndrome (MDS), including mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, paracoccidioidomycosis, cutaneous tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, leprosy, rhinoscleroma, midline NK/T-cell (NK) lymphoma and ANCA vasculitis.

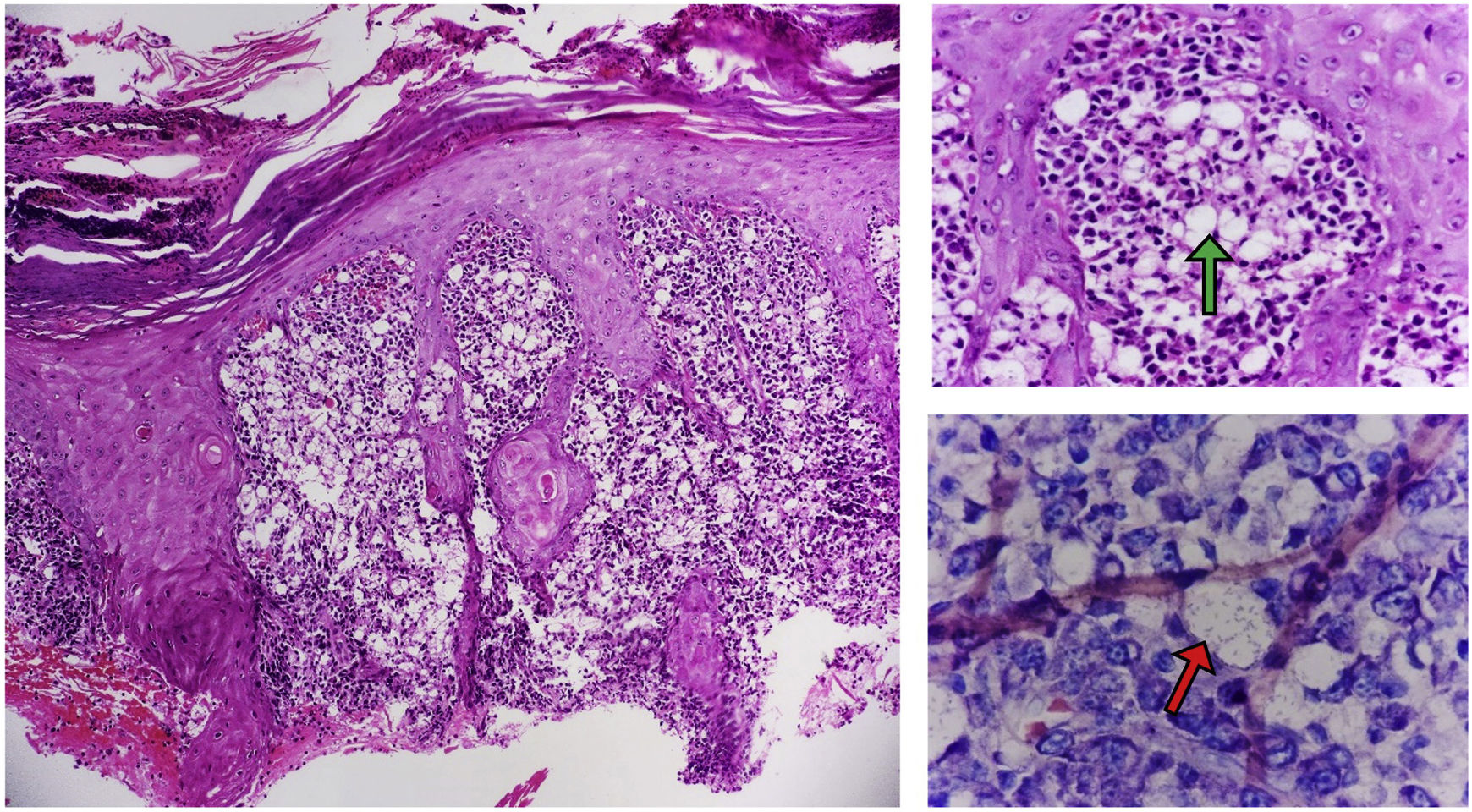

Clinical course and diagnosisOnce in hospital, skin biopsies were taken with punch biopsies for molecular tests, microbiology and histopathology. Direct tests for Leishmania spp. (Giemsa staining), fungi (potassium hydroxide staining [KOH]) and bacteria (Gram stain) were negative. There was also no growth of fungi, aerobic bacteria or mycobacteria in the skin cultures. Molecular tests for Leishmania spp. and for fungi (universal panel of mycoses) were also negative. Autoimmune causes such as ANCA vasculitis were ruled out. Last of all, histopathology examination of the skin detected nothing suggestive of a cancerous cause, such as midline NK lymphoma or skin cancer. In fact, the findings were suggestive of an infectious process. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia was observed, associated with a dense granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate made up of foamy histiocytes with bacillary structures inside (Mikulicz cells). As these findings were compatible with rhinoscleroma (Fig. 2), treatment with doxycycline was indicated (100mg/12h for six months).

Histopathology findings A) (H&E; ×100 magnification). B) (H&E; magnification ×400) Keratinised stratified squamous epithelium with reactive changes secondary to infiltration of the dermis by Mikulicz cells (green arrow) and plasma cells; C) (Giemsa stain; magnification ×1000). Histiocytes with bacilli in their cytoplasm (red arrow).

MDS encompasses a group of infectious, inflammatory and cancerous diseases which can cause destruction and deformity of the central facial region, including: midline NK lymphoma; non-melanoma skin cancer; ANCA vasculitis; and fungal (paracoccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, aspergillosis), parasitic (leishmaniasis) and bacterial (for example, leprosy, tuberculosis, syphilis) infections.1 Rhinoscleroma is a rare infectious aetiology of this syndrome and is caused by the gram-negative cocci-bacillus Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis, subspecies of K. pneumoniae.2 It is more common in young women, and is endemic in South America, Central America, Africa, India and Indonesia. It usually has a chronic clinical course and three stages of infection have been described.2 The first rhinitis or catarrhal phase involves chronic nasal and sinus symptoms and mucopurulent, foul-smelling nasal discharge with nasal obstruction. The second stage is described as granulomatous or proliferative and is characterised by thickening of the nasal mucosa and the development of obstructive granulomatous masses. Lastly is the sclerotic or scar phase, in which the lesions begin to heal, with nasal deformity and narrowing of the nasal passages.

The diagnosis can be made with the isolation of K. rhinoscleromatis in conventional culture media. However, it is only positive in 50% of patients. However, the diagnosis can be confirmed by the presence of Mikulicz cells or Russell bodies in the histopathology studies (Fig. 2).2,3 There is no established treatment regimen for rhinoscleroma and most case series report improvement after six months of antibiotic treatment. The medications used include trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole, cephalosporins, quinolones and tetracyclines.3

To conclude, rhinoscleroma is a rare condition which should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with MDS, especially in areas endemic for this disease.

FundingThis publication did not require funding of any kind.