This study sought to analyse differences in epidemiology and survival between women and men living with HIV (WLHIV and MLHIV) in the CoRIS cohort and the course of their disease over a 10-year period.

MethodsVariables of interest between WLHIV and MLHIV were compared. A trend analysis was performed using the Mantel–Haenszel test. Kaplan–Meier survival curves and a Cox regression analysis were used to study survival.

ResultsA total of 10,469 people were enrolled; of them, 1,742 (16.6%) were women. At the time of enrolment in the cohort, WLHIV, compared to MLHIV, had higher rates of transmission due to intravenous drug use (IDU), hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfection, AIDS-stage disease and foreign origin. They also had a worse immunovirological status and a lower educational level. These differences were maintained in the trend study. Regarding age, the women included in the cohort were older whereas the men were younger. In the comparative analysis between women according to place of origin, we found that the group of Spanish WLHIV featured older women with higher rates of IDU transmission and HCV coinfection, whereas the group of WLHIV born outside of Spain featured women with higher rates of syphilis infection. There were no major differences in relation to other characteristics such as educational level or disease status. Although sex was not a determinant of survival, conditions more prevalent in women were determinants of survival.

ConclusionsHIV-infected women presented at diagnosis with certain epidemiological and HIV-associated characteristics that made them more vulnerable. These trends became more marked or did not improve during the years of observation.

Analizar en la cohorte CoRIS las diferencias epidemiológicas y en la mortalidad entre mujeres y hombres que viven con VIH (MVVIH y HVVIH) y su evolución en el tiempo.

MétodosSe compararon las variables de interés entre MVVIH y HVVIH. Se realizó un análisis de tendencias usando la prueba de Mantel–Haenszel. Para estudiar la supervivencia se utilizaron las curvas de supervivencia de Kaplan Meier y un análisis de regresión de Cox.

ResultadosSe incluyeron un total de 10469 personas de las cuales 1742 (16,6%) eran mujeres. En el momento de inclusión en la cohorte las MVVIH con respecto a los HVVIH tenían un mayor porcentaje de transmisiones por el uso de drogas intravenosas (UDI), coinfección por el virus de la hepatitis C (VHC), estadio de sida y origen extranjero. También, presentaron una peor situación inmunovirológica y nivel de estudios. Estas diferencias se mantuvieron en el estudio de tendencias. En cuanto a la edad las mujeres que se incluyeron en la cohorte fueron cada vez más mayores y lo contrario sucedió con los hombres. En el análisis comparativo entre mujeres según su lugar de origen, encontramos mujeres más mayores, con más transmisión por UDI y coinfección por VHC en el grupo de las MVVIH españolas; en cambio, la infección por sífilis fue más frecuente entre las nacidas fuera de España. No hubo grandes diferencias en relación con otras características como el nivel de estudios o la situación de enfermedad. El sexo no fue un condicionante de supervivencia y sí factores que se asociaban más a las mujeres.

ConclusionesLas mujeres infectadas por el VIH se presentaron al diagnóstico con unas características epidemiológicas y asociadas a la infección por VIH que las hacen más vulnerables, y estas tendencias fueron acentuándose o no mejoraron durante los años de observación.

In 2015, around 17.8 million women over 15 years of age were living with HIV worldwide, accounting for 51% of the total adult population with HIV1. Data from 2018 provided by UNAIDS suggest that around 6,000 young women 15–24 years of age contract HIV infection every week2.

The number of new HIV infections among women varies significantly from region to region. In sub-Saharan Africa, women accounted for 56% of all new infections in adults; this percentage was even higher among female youth 15–24 years of age1. By contrast, according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), 6,948 new HIV infections (2.6 per 100,000 population) were reported in women in the European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA) in 20163. In Spain, the rate of new HIV diagnoses in women is 2.2 per 100,000 population, compared to 12.5 per 100,000 population in men4. It is worth noting that rates of late diagnosis and advanced disease in Spain are 47.8% and 27.4%, respectively; both are higher in women than in men4. Despite being a minority group, an estimated 27,000 women are living with HIV in Spain5. In 2018, 60% of new infections in Spain were in women born outside of Spain4. This could point to the greater vulnerability among women who have arrived in Spain in the most recent years of the epidemic.

Despite the size of the group as a whole, women living with HIV (WLHIV) have been very under-represented in the development of new drugs and research has not been focused on their problems6. Another very important factor in many regions of the world is the greater vulnerability of the WLHIV population; in many countries, they live in communities without appropriate access to the health system and with very high poverty as well as domestic violence and substance abuse7.

At the start of the HIV epidemic, some studies reported higher rates of disease progression to AIDS and death in women8. Later studies attributed this to women's more limited access to antiretroviral therapy and greater vulnerability due to social characteristics that accompany the social role of being a woman9.

The objective of this study was to analyse any differences in epidemiology, progression and survival between WLHIV and men living with HIV (MLHIV) in a large group of women in the Spanish AIDS research network cohort (CoRIS) over a ten-year period. An additional objective aim was to characterise WLHIV by origin.

Material and methodsDescription of the cohortThe CoRIS is an open, prospective and multicentre cohort of adult patients living with HIV naïve to antiretroviral therapy. It was created in 2004 and contains epidemiological and laboratory data about the patients enrolled10. The study period analysed was from 1 January 2004 to 30 June 2014 (10 years).

Variables analysed and data analysisThis analysis used the following variables collected from the CoRIS, some of which have been recategorised: sex (male or female), origin (Spanish versus any other origin), level of education (categorised as university education or not), most likely mechanism of infection (men who have sex with men, sexual transmission, intravenous drug use, blood product transfusions, vertical transmission, tattoos or other mechanisms, which were recategorised as heterosexual sexual transmission versus all other mechanisms, homosexual sexual transmission versus all other mechanisms, and intravenous drug use [IDU] versus all other mechanisms), cohort inclusion date, clinical stage (CDC1993), AIDS-defining diseases (whether manifest or not), other diseases of interest, CD4 count (<200 versus ≥200 and <350 versus ≥350 cells/ml), viral load (≥105 copies/ml versus ≤105 copies/ml), baseline hepatitis B virus serology results (HBcAb, HBsAb and HBsAg), hepatitis C and syphilis, and any death during follow-up and cause of death (HIV-related infection, HIV-related neoplasm, non–HIV-related infection, liver disease, non–HIV-related neoplasm, cardiovascular disease, intravenous drug use, other or unknown).

To analyse changes in the variables over the course of the study, three consecutive periods were chosen for convenience: period 1, from January 2004 to December 2007; period 2, from January 2008 to December 2010; and period 3, from January 2011 to June 2014.

The overall distribution of patients was analysed as per the different epidemiological and clinical variables. Subsequently, all the variables considered were compared according to sex by univariate analysis, using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and Student's t test for continuous variables. To assess whether and how the demographic and clinical variables changed over time, a trend analysis of each variable in men and women was performed using the Mantel–Haenszel test for each variable and for each of the three time periods established. An analysis stratified by origin was performed on the WLHIV group. To analyse whether being a woman had any impact on time elapsed from cohort inclusion to death, Kaplan–Meier curves were drawn and compared using the log-rank test. A Cox regression analysis was performed, using an estimation model in which the effect of sex on the survival variable was adjusted for the possible independent variables considered clinically and/or statistically significant — age, education, AIDS stage, baseline CD4 count and hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfection — for each of the three time periods established. The effect of gender on the death variable was studied independently in each of the three time periods as an interaction between gender and time period was identified (p = 0.03). A univariate analysis was also performed to compare causes of death by sex.

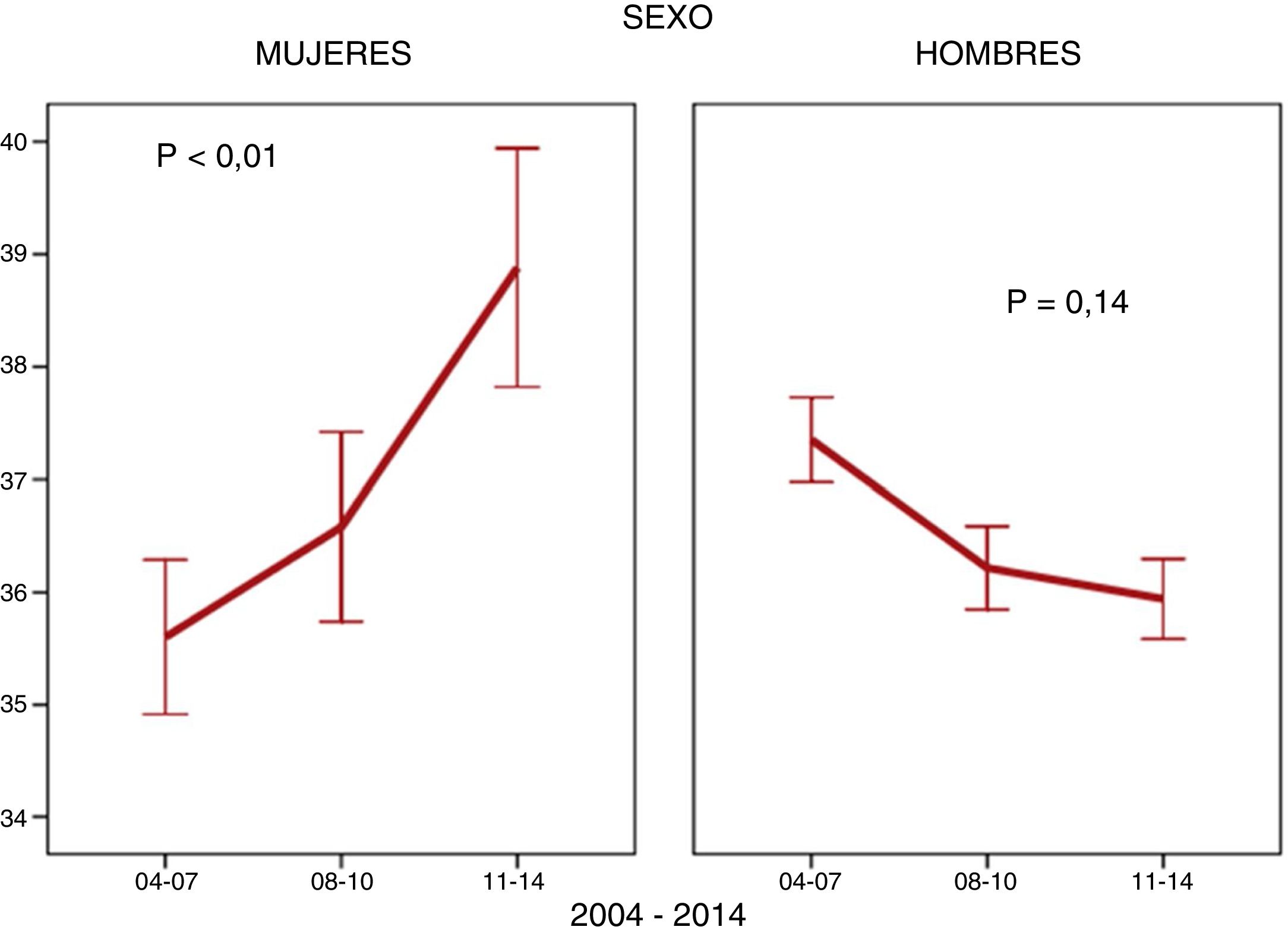

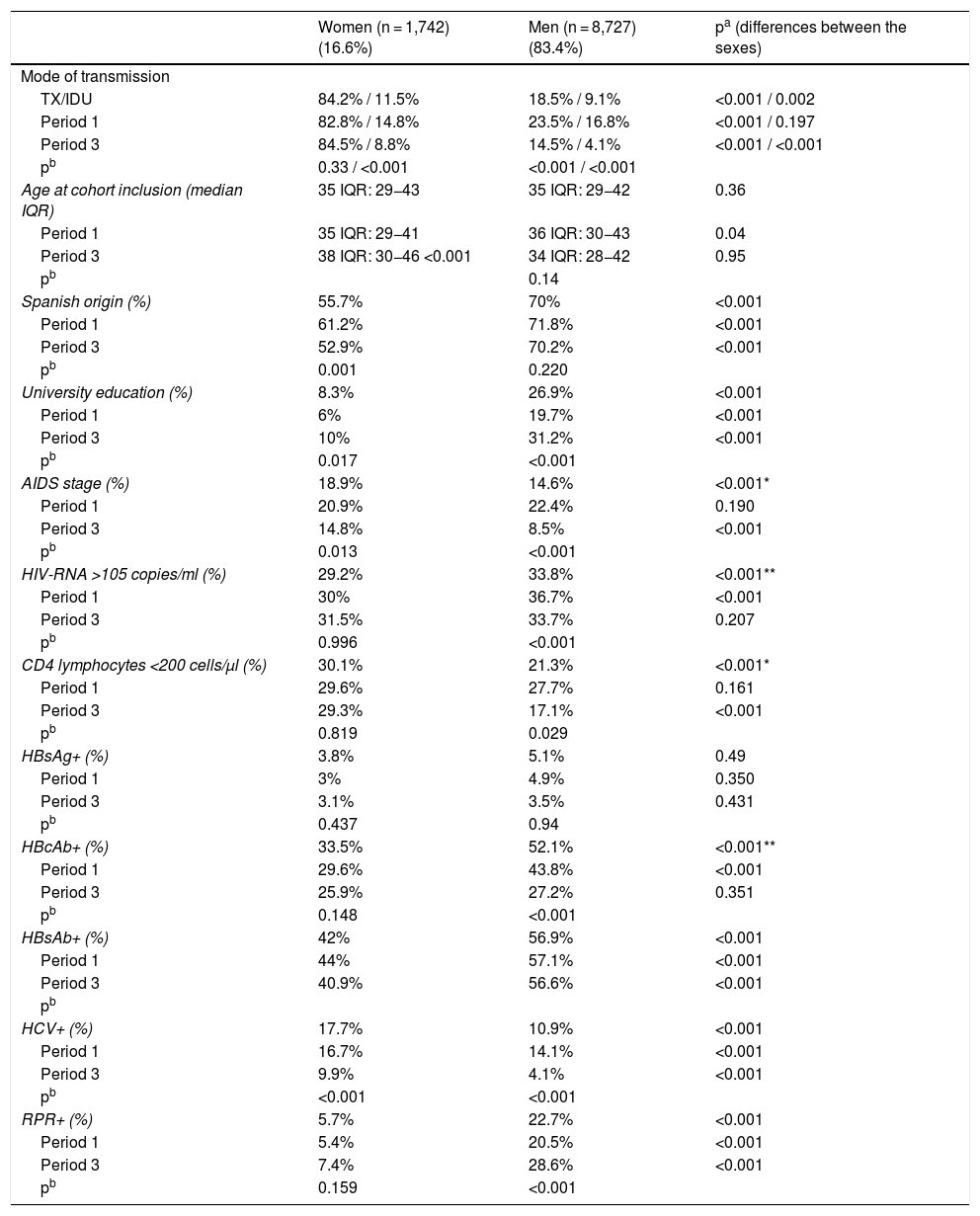

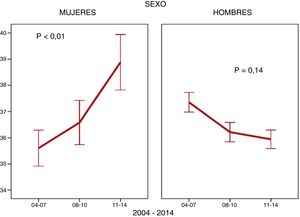

ResultsA total of 10,469 patients living with HIV were included; 1,742 (16.6%) of them were women. The number of women enrolled in the cohort fell from 756 (21.7%) to 420 (11.7%) (p < 0.001) between the first and the third period. The mean age ±SD of WLHIV was 37 ± 10 years at the time they were enrolled in the cohort. They had low CD4 counts at diagnosis and high HCV coinfection rates. A considerable number of women were foreign and had a low level of education (Table 1). With regard to how the above variables changed over the course of the study, a drop in IDU coinciding with a decline in HCV coinfected women was observed in WLHIV. The proportion of women included in the AIDS stage also decreased. However, other characteristics behaved differently. The age of women at cohort inclusion increased (Fig. 1). This was particularly apparent in the over-50 age group, which increased from 8.6% (65) in the first period to 15.2% (64) in the third period (p < 0.001). The percentage of WLHIV of non-Spanish origin also increased, while the number of university-educated women, the parameters of viral load and CD4 count, and rates of hepatitis B virus (HBV) coinfection and syphilis infection at diagnosis remained stable (Table 1). In MLHIV, the most significant finding was an increase in syphilis coinfection rates (Table 1), particularly among men who have sex with men (MSM) (86.7%) compared with men who do not have sex with men (13.3%).

Baseline characteristics and trends of the population studied.

| Women (n = 1,742) (16.6%) | Men (n = 8,727) (83.4%) | pa (differences between the sexes) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mode of transmission | |||

| TX/IDU | 84.2% / 11.5% | 18.5% / 9.1% | <0.001 / 0.002 |

| Period 1 | 82.8% / 14.8% | 23.5% / 16.8% | <0.001 / 0.197 |

| Period 3 | 84.5% / 8.8% | 14.5% / 4.1% | <0.001 / <0.001 |

| pb | 0.33 / <0.001 | <0.001 / <0.001 | |

| Age at cohort inclusion (median IQR) | 35 IQR: 29−43 | 35 IQR: 29−42 | 0.36 |

| Period 1 | 35 IQR: 29−41 | 36 IQR: 30−43 | 0.04 |

| Period 3 | 38 IQR: 30−46 <0.001 | 34 IQR: 28−42 | 0.95 |

| pb | 0.14 | ||

| Spanish origin (%) | 55.7% | 70% | <0.001 |

| Period 1 | 61.2% | 71.8% | <0.001 |

| Period 3 | 52.9% | 70.2% | <0.001 |

| pb | 0.001 | 0.220 | |

| University education (%) | 8.3% | 26.9% | <0.001 |

| Period 1 | 6% | 19.7% | <0.001 |

| Period 3 | 10% | 31.2% | <0.001 |

| pb | 0.017 | <0.001 | |

| AIDS stage (%) | 18.9% | 14.6% | <0.001* |

| Period 1 | 20.9% | 22.4% | 0.190 |

| Period 3 | 14.8% | 8.5% | <0.001 |

| pb | 0.013 | <0.001 | |

| HIV-RNA >105 copies/ml (%) | 29.2% | 33.8% | <0.001** |

| Period 1 | 30% | 36.7% | <0.001 |

| Period 3 | 31.5% | 33.7% | 0.207 |

| pb | 0.996 | <0.001 | |

| CD4 lymphocytes <200 cells/μl (%) | 30.1% | 21.3% | <0.001* |

| Period 1 | 29.6% | 27.7% | 0.161 |

| Period 3 | 29.3% | 17.1% | <0.001 |

| pb | 0.819 | 0.029 | |

| HBsAg+ (%) | 3.8% | 5.1% | 0.49 |

| Period 1 | 3% | 4.9% | 0.350 |

| Period 3 | 3.1% | 3.5% | 0.431 |

| pb | 0.437 | 0.94 | |

| HBcAb+ (%) | 33.5% | 52.1% | <0.001** |

| Period 1 | 29.6% | 43.8% | <0.001 |

| Period 3 | 25.9% | 27.2% | 0.351 |

| pb | 0.148 | <0.001 | |

| HBsAb+ (%) | 42% | 56.9% | <0.001 |

| Period 1 | 44% | 57.1% | <0.001 |

| Period 3 | 40.9% | 56.6% | <0.001 |

| pb | |||

| HCV+ (%) | 17.7% | 10.9% | <0.001 |

| Period 1 | 16.7% | 14.1% | <0.001 |

| Period 3 | 9.9% | 4.1% | <0.001 |

| pb | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| RPR+ (%) | 5.7% | 22.7% | <0.001 |

| Period 1 | 5.4% | 20.5% | <0.001 |

| Period 3 | 7.4% | 28.6% | <0.001 |

| pb | 0.159 | <0.001 |

HBcAb: hepatitis B virus core antibody; HBsAb: hepatitis B virus surface antibody; HBsAg: hepatitis B virus surface antigen; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HIV-RNA: viral load of HIV ribonucleic acid; HTX: heterosexual transmission; IDU: intravenous drug use; RPR: rapid plasma reagin test for syphilis infection.

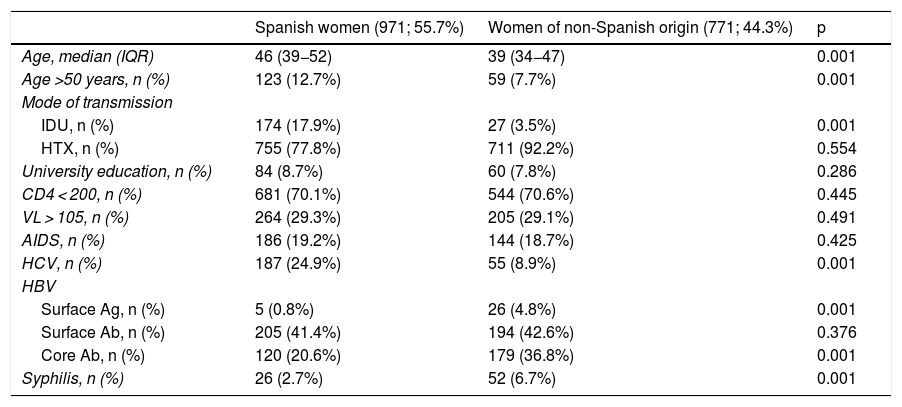

A comparison of WLHIV by place of origin revealed that Spanish women tended to be older at cohort inclusion than foreign women (Table 2). A comparison of the two groups of women found that the proportion of Spanish women over 50 years of age increased from 8.6% to 19.8% (p < 0.001), while in foreign women this proportion remained stable over the three time periods (8.5%–10%, p = 0.553). Although the percentage of WLHIV who acquired infection through IDU decreased overall, this decrease was only statistically significant for Spanish women (21.4%–14%, p = 0.010). The trend in the group of foreign women remained stable (4.41%–3%, p = 0.36). The percentage of women who had studied at university was similar in the two groups and was very low. In total, 6.5% of Spanish women were university-educated in the first period; this figure increased slightly to 10.8% (p = 0.035). Similarly, 5.1% of foreign women were university-educated in the first period; this percentage rose to 9.1% in the third period (p = 0.754). Regarding parameters specific to HIV infection (AIDS stage, viral load and CD4 count), no statistically significant differences between the two groups of women were identified. The percentage of women with a CD4 count below 200 at diagnosis remained stable in both Spanish women (29.4%–30.2%; p = 0.795) and foreign women (28.3%-28.3%; p = 0.923). No differences were observed between period 1 (p = 0.411) and period 3 (p = 0.375) when comparing the two groups of women. Viral load behaved in a similar way. The percentage of Spanish women with >105 copies/ml at cohort inclusion increased from 29.8% in the first period to 34.6% in the third (p = 0.412), while the corresponding percentage of foreign women ranged from 30.4% to 27.9% (p = 0.556). Differences were observed between the two groups of women in the third period, but they were not statistically significant (p = 0.093), and there were no differences in the first period (p = 0.467). The behaviour and trend of the AIDS stage variable was also similar between the two groups of women. In Spanish women, the percentage fell from 22% in the first period to 15.3% in the third (p = 0.027); in foreign women, it remained stable (dropping from 19.1% to 14.1%, p = 0.230). With respect to HCV coinfection, the percentage of infected Spanish women fell from 22.4% in the first period to 16.2% (p = 0.031). In foreign women, these percentages were 8.3% in the first period and 3.8% in the third period (p = 0.052). No differences in trends over time in syphilis rates were observed between the two groups of women. In Spanish women, the rate increased from 2.2% in the first period to 4.1% in the third (p = 0.177), while in foreign women it fell from 7.2% to 6.6% (p = 0.772). A comparison of the rates between the two groups of women revealed that the rate in foreign women was higher than the rate in Spanish women (p = 0.001), but the differences were no longer statistically significant in the third period (p = 0.175).

Comparison of epidemiological characteristics between women of Spanish and non-Spanish origin.

| Spanish women (971; 55.7%) | Women of non-Spanish origin (771; 44.3%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 46 (39−52) | 39 (34−47) | 0.001 |

| Age >50 years, n (%) | 123 (12.7%) | 59 (7.7%) | 0.001 |

| Mode of transmission | |||

| IDU, n (%) | 174 (17.9%) | 27 (3.5%) | 0.001 |

| HTX, n (%) | 755 (77.8%) | 711 (92.2%) | 0.554 |

| University education, n (%) | 84 (8.7%) | 60 (7.8%) | 0.286 |

| CD4 < 200, n (%) | 681 (70.1%) | 544 (70.6%) | 0.445 |

| VL > 105, n (%) | 264 (29.3%) | 205 (29.1%) | 0.491 |

| AIDS, n (%) | 186 (19.2%) | 144 (18.7%) | 0.425 |

| HCV, n (%) | 187 (24.9%) | 55 (8.9%) | 0.001 |

| HBV | |||

| Surface Ag, n (%) | 5 (0.8%) | 26 (4.8%) | 0.001 |

| Surface Ab, n (%) | 205 (41.4%) | 194 (42.6%) | 0.376 |

| Core Ab, n (%) | 120 (20.6%) | 179 (36.8%) | 0.001 |

| Syphilis, n (%) | 26 (2.7%) | 52 (6.7%) | 0.001 |

Core Ab: core antibody; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HTX: heterosexual transmission; IDU: intravenous drug use; n: number of people; Surface Ab: surface antibody; Surface Ag: surface antigen; VL: viral load.

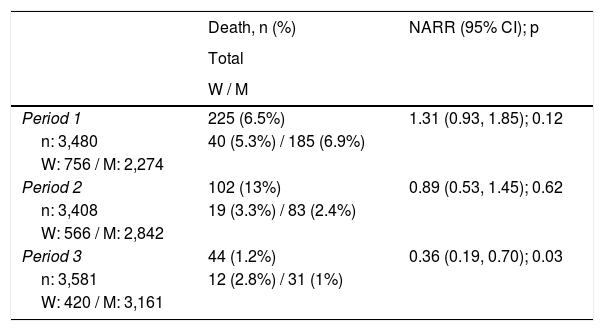

In total, 371 deaths (3.5%) occurred over the 10 years of the study; among those who died, 71 (4.1%) were women and 300 (3.4%) were men. No overall differences in mortality rates were observed between the two groups (p = 0.83).

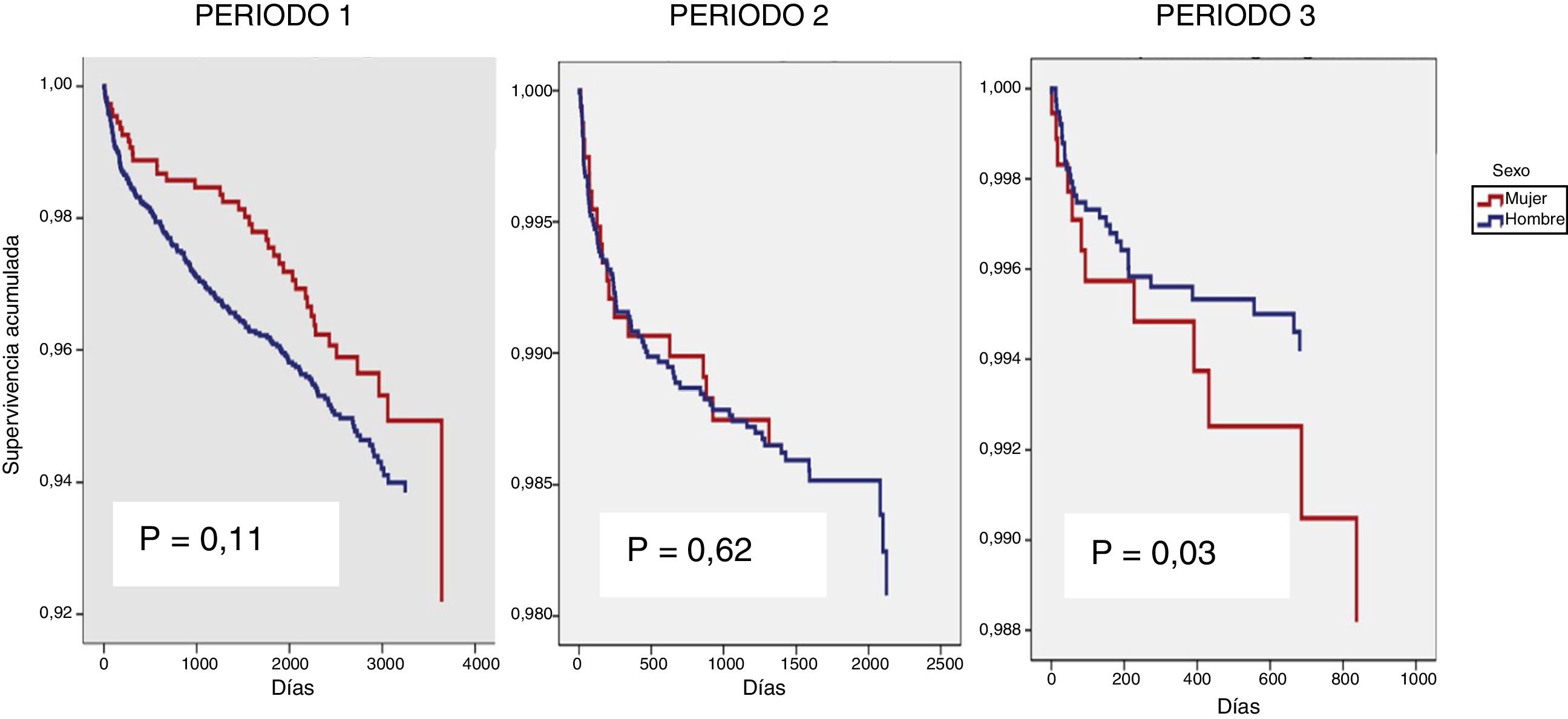

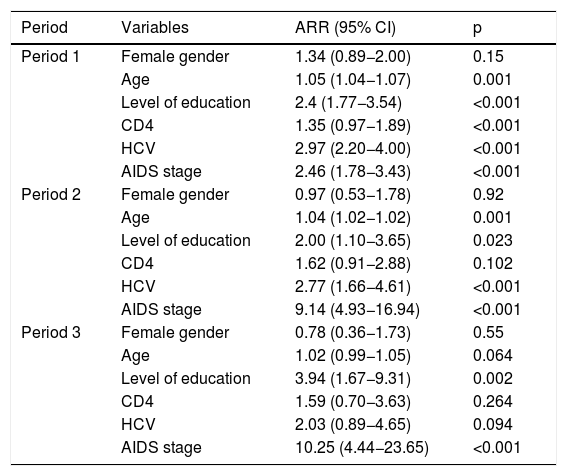

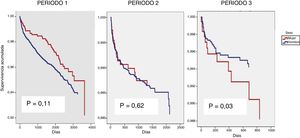

The effect of gender on the death variable was studied independently in each of the three time periods as an interaction between gender and time period had been identified (p = 0.03) (Fig. 2). In the unadjusted model, gender had a beneficial effect in period 1, a neutral effect in period 2 and a harmful effect in period 3 (Table 3). Adjusting for the variables described in the methodology, it was not gender that seemed to affect time to death (Table 4), but rather other factors more common in women.

Percentage of mortality by period and relative risk for survival not adjusted according to sex.

| Death, n (%) | NARR (95% CI); p | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | ||

| W / M | ||

| Period 1 | 225 (6.5%) | 1.31 (0.93, 1.85); 0.12 |

| n: 3,480 | 40 (5.3%) / 185 (6.9%) | |

| W: 756 / M: 2,274 | ||

| Period 2 | 102 (13%) | 0.89 (0.53, 1.45); 0.62 |

| n: 3,408 | 19 (3.3%) / 83 (2.4%) | |

| W: 566 / M: 2,842 | ||

| Period 3 | 44 (1.2%) | 0.36 (0.19, 0.70); 0.03 |

| n: 3,581 | 12 (2.8%) / 31 (1%) | |

| W: 420 / M: 3,161 |

n: number included; NARR: non-adjusted relative risk; M: men; W: women.

Final estimated Cox model: influence of sex on survival.

| Period | Variables | ARR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Period 1 | Female gender | 1.34 (0.89−2.00) | 0.15 |

| Age | 1.05 (1.04−1.07) | 0.001 | |

| Level of education | 2.4 (1.77−3.54) | <0.001 | |

| CD4 | 1.35 (0.97−1.89) | <0.001 | |

| HCV | 2.97 (2.20−4.00) | <0.001 | |

| AIDS stage | 2.46 (1.78−3.43) | <0.001 | |

| Period 2 | Female gender | 0.97 (0.53−1.78) | 0.92 |

| Age | 1.04 (1.02−1.02) | 0.001 | |

| Level of education | 2.00 (1.10−3.65) | 0.023 | |

| CD4 | 1.62 (0.91−2.88) | 0.102 | |

| HCV | 2.77 (1.66−4.61) | <0.001 | |

| AIDS stage | 9.14 (4.93−16.94) | <0.001 | |

| Period 3 | Female gender | 0.78 (0.36−1.73) | 0.55 |

| Age | 1.02 (0.99−1.05) | 0.064 | |

| Level of education | 3.94 (1.67−9.31) | 0.002 | |

| CD4 | 1.59 (0.70−3.63) | 0.264 | |

| HCV | 2.03 (0.89−4.65) | 0.094 | |

| AIDS stage | 10.25 (4.44−23.65) | <0.001 |

ARR: adjusted relative risk; CD4: CD4 lymphocytes; HCV: hepatitis C virus.

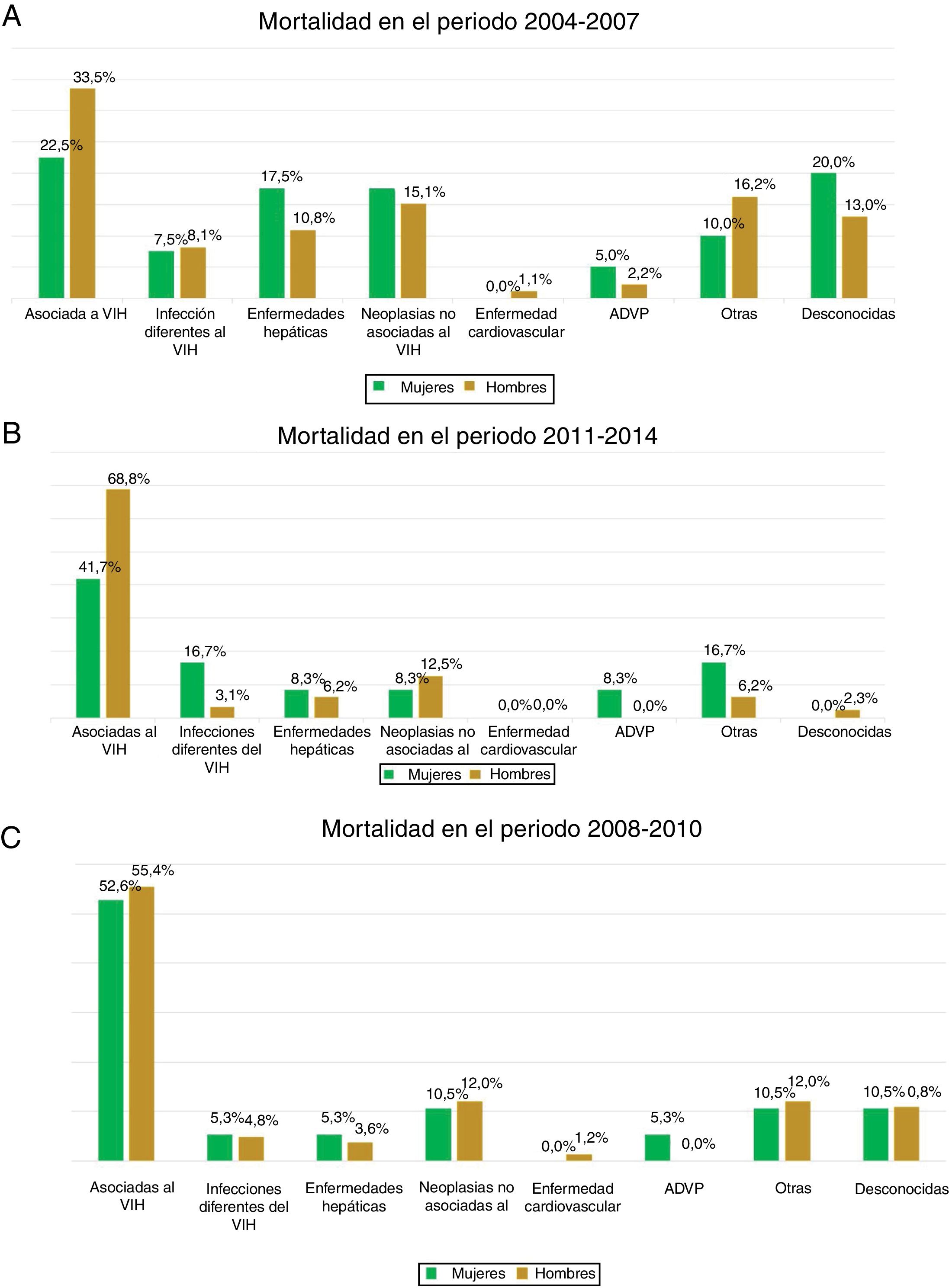

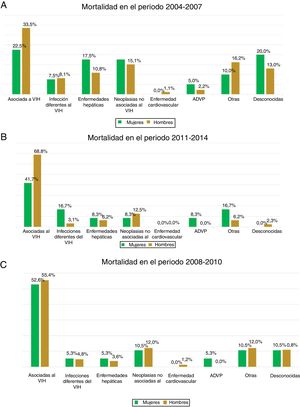

The most common cause of death was associated with HIV infection itself, which accounted for 41.5% of all deaths, followed by non–HIV-related neoplasm (14%). No statistically significant differences associated with sex were observed in the various causes of death in any of the three time periods analysed (p = 0.374) (Fig. 3).

DiscussionThis analysis gender-based analysis found clear epidemiological differences between WLHIV and MLHIV, as well as between WLHIV from Spain and WLHIV not from Spain. Hence, these can be considered a set of different epidemics, not only for men and women, but also for the different groups of women, who furthermore followed different courses throughout the observation period.

The median age of the women enrolled into the cohort was higher than that of the men, and the proportion of women over 50 years of age increased with each time period. The stratified analysis revealed that this increase in age at diagnosis only applied to women of Spanish origin; age at diagnosis of women not from Spain remained stable. This finding was important because in women of childbearing potential, the choice of antiretroviral therapy to be administered is influenced by the desire to have a baby and the use of an effective contraceptive method11, whereas in later life comorbidities, particularly osteoporosis and cardiovascular risk factors, are of primary concern12. By contrast, the age of men enrolled in the cohort did not vary. One possible explanation for this is the decrease in parenteral transmission, which occurs in younger women13, and increased heterosexual transmission, which can occur at any age. Older women have been found to be less likely to use a condom due to the lack of risk of pregnancy and the discomfort that can be caused by vaginal dryness14. They have also been found to be more susceptible to HIV infection due to vaginal changes15. A French study published in 201616 found the average age of people diagnosed with HIV infection to be very similar in both sexes, while other studies published in 2014 in Canada17, Italy18 and Switzerland19 found that, on average, the men were slightly older than the women. Women not from Spain were younger than Spanish women, and the percentage of women over 50 years of age was 7.7%. A recent European study also found that women 31–50 years of age comprised the largest percentage (62%) whereas women over 50 years of age accounted for only 12%20. Another Spanish study published in 2018 identified a median age of 35 years in this subgroup of non-Spanish women21, who were even younger than the foreign women enrolled in the CoRIS and analysed in this study.

IDU was seen to be higher in WLHIV compared to men. In other cohorts, such as the French cohort16 and the Canadian cohort17, the number of women infected with HIV through IDU was also higher than in men. However, in other study groups, like the Italian SCOLTA cohort18 and the Ukrainian cohort22, IDU was higher among men. The European Drug Report 2016 reported that use of heroin, currently the most widely used intravenous drug in Europe, was generally lower among women (20%) than men (80%)23. There are likely different regional factors that lead to a higher proportion of drug use in one sex or the other. It was striking to find that the likely route of HIV infection different depending on the origin of the women. This is not reflected in most of the national cohorts reviewed and would suggest the need for different HIV screening and prevention measures.

Another difference associated with sex was level of education. Women had a lower level of education compared to men, which made them more vulnerable than their male counterparts. There were also more foreign women than foreign men, with an upwards trend in the number of foreign women. These finding were consistent with those in other cohorts, such as the Swiss cohort19, and with European epidemiological data, particularly central and eastern European countries as well as Russia3.

Level of education and country of origin other than their country of residence predisposed the women diagnosed in the CoRIS to greater vulnerability than the men. In previous studies in this same cohort, the authors identified greater diagnostic delay in non-Spanish people as well as a worse immunovirological response24.

A significant decrease in HCV coinfection was seen in both sexes. However, it was not seen in the group of non-Spanish women, who had a lower HCV prevalence than the group of Spanish women. The main reason for this decrease was reduced drug use, primarily intravenous heroin, which was very popular in the 1980s but then gave way in the 1990s and beyond to other types of oral and inhaled drugs25. To date, the recent acute HCV infection epidemics that have afflicted the MSM population have not led to an increase in the prevalence of hepatitis C in men compared to women26.

At cohort inclusion, the immunological status of women was worse than that of men. Moreover, while men’s immunological status improved and their viral load at diagnosis decreased over the years, this same change was not seen in women. Women’s higher rates of IDU and HCV coinfection could partially explain their worse immunological status27. A previous gender-based analysis performed in this same cohort found that, between 1996 and 2003, women were diagnosed with a better median CD4 count than men28. Our results, which found no differences between 2004 and 2008, were consistent with these earlier findings. Taking into account the prior analysis, the fact that women's immunological status is worse than men’s could be partially explained by the greater vulnerability of the women enrolled in the cohort in more recent years, reflected in two very clear indicators: a lower cultural status and a higher number of immigrants. Spanish epidemiological data from recent years corroborate these results, with a higher proportion of late diagnoses being identified in women29. Other factors that could impact late diagnosis in women include the fact that they are perceived to be at lower risk of contracting HIV — both by themselves and by the healthcare professionals who treat them — and a lack of awareness of the risk factors for acquiring HIV infection. The next Spanish study, published in 2011, reported that being a heterosexual man, being a parenteral drug user and being older were predisposing factors to delayed diagnosis. Being female and being of non-Spanish origin were also associated with a higher rate of diagnostic delay; this rate was lower in the group of MSM30.

Women’s viral load at cohort inclusion was lower than men’s. Differences in viral load between men and women have been known for years31. The authors of two meta-analyses concluded that women's HIV viral load levels are up to 41% lower than men’s32. A later study that evaluated seroconversion in patients with IDU found that HIV viral load levels were lower in women at diagnosis, but subsequently increased more quickly in women such that viral load levels ended up being similar between the sexes33. These findings do not seem to have any clinical repercussions for progression to AIDS or mortality34.

The proportion of women diagnosed with syphilis coinfection at HIV diagnosis was much lower than the corresponding proportion of men and remained stable throughout the study. By contrast, over the years, a significant increase in syphilis infection was seen in men, particularly MSM. This has also been observed on an epidemiological level and is consistent with the increased incidence of syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections in young MSM, especially in developed countries35. Another difference identified was the higher prevalence of syphilis coinfection in the group of foreign women. This finding was consistent with other published studies36. A likely explanation is that foreign women tend to contract HIV by heterosexual transmission, which entails an increased risk of transmission of other sexually transmitted infections.

HBV coinfection is a common finding in patients living with HIV. A considerable percentage of our cohort had serological markers of past infection, whether cured or not, while the rate of active HBV infection did not exceed 5% for either sex. A comparison with other cohorts revealed that the prevalence of chronic HBV infection varies by risk group and geographic area37. The epidemiological data for HBV coinfection in our cohort are very similar to other countries in western Europe and the United States of America, where more than half of homosexual men living with HIV have serology consistent with prior HBV infection, and 5%–10% have chronic hepatitis and are HBsAg-positive38. According to our results, the rate of HBV infection was higher among men, indicated by a higher percentage of anti-HBc, but the differences were only statistically significant in the first period. The fact that the men in our cohort had a higher level of education and fewer of them were immigrants compared to the women might have meant that they had greater access to the health system and therefore a higher rate of HBV vaccination, which is included in Spain’s routine vaccination schedule.

MortalityOur results showed that the impact of sex on mortality differed depending on the period studied. This change in the behaviour of the sex variable in relation to survival was probably associated with the tendency of the women recently enrolled in the cohort to be more vulnerable, older, more likely to be foreign and more likely to have a lower level of education than the men. All of these factors were associated with worse survival. Other variables closely associated with HIV survival, such as AIDS stage, CD4 count and HCV coinfection, were also found to be more common in women, and some of them tended not to improve over the three study periods.

A Spanish study conducted in 2016 in a cohort of 1,070 patients analysed the different causes of death. The authors concluded that they found no differences associated with sex39. In the Swiss cohort, between 2005 and 2009, 459 deaths (5.1%) were recorded, corresponding to 340 men and 119 women, with no statistically significant differences. The authors concluded that although there were no sex-associated differences in mortality, different conditions did exist (later diagnosis in women and a higher number of foreign women) that made women more vulnerable40.

Analysis of the causes of death in the cohort revealed that they were similar among men and women; this was consistent with findings in other cohorts, such as the Swiss cohort40. In our study, both the different causes of death and the changes over time therein were very similar between men and women and remained stable throughout the study period. A study comparing causes of death between a population living with HIV and a population without HIV was recently published. It included 13,729 people living with HIV who were compared to 510,313 people not carrying the virus. The infected population included 2,712 women (19.75%). No differences in mortality rates or causes of death were found between the sexes; the mortality ratios per 1,000 population were comparable for men and women41. By contrast, in a study by the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) cohort group on causes of death in the HIV population, the risk of death was 1.32 times higher in men than in women, but only within the “other causes” subgroup out of all the causes of death analysed in the study42.

Causes of death directly associated with HIV infection were most common in our cohort, followed by non–HIV-related neoplasm, with no differences between the sexes. A study by Weber et al.40 identified a changing trend in the causes of death of patients infected with HIV. Death directly caused by HIV infection is decreasing significantly thanks to greater patient access to antiretroviral treatment, improvements in diagnostic tools and use thereof, and increased ageing of the general population. Non–HIV-related neoplasm, liver disease, non–HIV-related infections and cardiovascular disease are becoming more common causes of death43. Despite this change in the causes of death of patients infected with HIV, the vast majority of studies have found that HIV itself continues to figure prominently among causes of death in patients with HIV29. The data reported in our cohort were consistent with the results published in different cohorts, including the Italian cohort44, the Danish cohort45, the English cohort46, the French cohort47 and the American cohort48.

The fact that a significant diagnostic delay persisted in both sexes in the last observation period (29% and 17%) is undoubtedly the most influential factor in higher mortality with HIV infection, since people living with HIV in an advanced state of immunosuppression respond more poorly to treatment and are at higher risk of progression to AIDS and death49.

ConclusionsThere are fewer women than men in the CoRIS and their numbers have been decreasing over time. Women living with HIV have different epidemiological characteristics from their male counterparts, including a tendency to be older, to have a lower level of education and to come from outside Spain. All of these characteristics lead to greater vulnerability due to the social role of being a woman. Strikingly, late presentation and advanced disease at diagnosis were more common in women than men overall, and did not improve during follow-up. There were also some differences between Spanish women and foreign women living with HIV: Spanish women tended to be older and to contract HIV by heterosexual transmission or IDU, whereas non-Spanish women were more likely to have syphilis coinfection.

Gender did not significantly influence the survival of people living with HIV. No differences in the various causes of death were found in this cohort.

FundingThis study was funded by grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III [Carlos III Health Institute] through the Red Temática de Investigación Cooperativa en Sida [Cooperative AIDS Research Network] (RD06/006, RD12/0017/0018 and RD16/0002/0006) as part of the R&D&I Spanish National Plan, and cofunded by the ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación [Carlos III Health Institute Subdirectorate General for Evaluation] and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). The funding agencies played no role in study design, data collection or analysis, the decision to publish the study or manuscript preparation. The authors are solely responsible for the final content and the interpretation of the results.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This study would not have been possible without the collaboration of all the patients, doctors and nurses, as well as the data administrators involved in the project.

- •

Executive committee

Santiago Moreno, Inma Jarrín, David Dalmau, María Luisa Navarro, María Isabel González, Federico García, Eva Poveda, José Antonio Iribarren, Félix Gutiérrez, Rafael Rubio, Francesc Vidal, Juan Berenguer, Juan González, M. Ángeles Muñoz-Fernández.

- •

Fieldwork and data management and analysis

- •

Inmaculada Jarrin, Belén Alejos, Cristina Moreno, Carlos Iniesta, Luis Miguel García Sousa, Nieves Sanz Pérez, Marta Rava.

- •

HIV biobank of Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón [Gregorio Marañón University General Hospital]

M. Ángeles Muñoz-Fernández, Irene Consuegra-Fernández.

- •

Hospital General Universitario de Alicante [Alicante University General Hospital] (Alicante)

Esperanza Merino, Gema García, Irene Portilla, Iván Agea, Joaquín Portilla, José Sánchez-Payá, Juan Carlos Rodríguez, Lina Gimeno, Livia Giner, Marcos Díez, Melissa Carreres, Sergio Reus, Vicente Boix, Diego Torrús.

- •

Hospital Universitario de Canarias [Canary Islands University Hospital] (San Cristóbal de la Laguna)

Ana López Lirola, Dácil García, Felicitas Díaz-Flores, Juan Luis Gómez, María del Mar Alonso, Ricardo Pelazas, Jehovana Hernández, María Remedios Alemán, María Inmaculada Hernández.

- •

Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias [Asturias Central University Hospital] (Oviedo)

Víctor Asensi, Eulalia Valle, María Eugenia Rivas Carmenado, Tomás Suárez-Zarracina Secades, Laura Pérez Is.

- •

Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre [12 de Octubre University Hospital] (Madrid)

Rafael Rubio, Federico Pulido, Otilia Bisbal, Asunción Hernando, Lourdes Domínguez, David Rial Crestelo, Laura Bermejo, Mireia Santacreu.

- •

Hospital Universitario de Donostia [Donostia University Hospital] (Donostia/San Sebastián)

José Antonio Iribarren, Julio Arrizabalaga, María José Aramburu, Xabier Camino, Francisco Rodríguez-Arrondo, Miguel Ángel von Wichmann, Lidia Pascual Tomé, Miguel Ángel Goenaga, M. Jesús Bustinduy, Harkaitz Azkune, Maialen Ibarguren, Aitziber Lizardi, Xabier Kortajarena, M. Pilar Carmona Oyaga, Maitane Umerez Igartua.

- •

Hospital General Universitario de Elche [Elche University General Hospital] (Elche)

Félix Gutiérrez, Mar Masiá, Sergio Padilla, Catalina Robledano, Joan Gregori Colomé, Araceli Adsuar, Rafael Pascual, Marta Fernández, José Alberto García, Xavier Barber, Vanessa Agullo Re, Javier Garcia Abellán, Reyes Pascual Pérez, María Roca.

- •

Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol [Germans Trias i Pujol University Hospital] (Can Ruti) (Badalona)

Roberto Muga, Arantza Sanvisens, Daniel Fuster.

- •

Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (Madrid)

Juan Berenguer, Juan Carlos López Bernaldo de Quirós, Isabel Gutiérrez, Margarita Ramírez, Belén Padilla, Paloma Gijón, Teresa Aldamiz-Echevarría, Francisco Tejerina, Francisco José Parras, Pascual Balsalobre, Cristina Diez, Leire Pérez Latorre, Chiara Fanciulli.

- •

Hospital Universitari de Tarragona Joan XXIII [Joan XXIII Tarragona University Hospital] (Tarragona)

Francesc Vidal, Joaquín Peraire, Consuelo Viladés, Sergio Veloso, Montserrat Vargas, Montserrat Olona, Anna Rull, Esther Rodríguez-Gallego, Verónica Alba, Alfonso Javier Castellanos, Miguel López-Dupla.

- •

Hospital Universitario y Politécnico de La Fe [La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital] (Valencia)

Marta Montero Alonso, José López Aldeguer, Marino Blanes Juliá, María Tasias Pitarch, Iván Castro Hernández, Eva Calabuig Muñoz, Sandra Cuéllar Tovar, Miguel Salavert Lletí, Juan Fernández Navarro.

- •

Hospital Universitario La Paz [La Paz University Hospital]/Instituto de Investigación Hospital Universitario La Paz [La Paz University Hospital Research Institute] (IdiPAZ)

Juan González-García, Francisco Arnalich, José Ramón Arribas, Jose Ignacio Bernardino de la Serna, Juan Miguel Castro, Ana Delgado Hierro, Luis Escosa, Pedro Herranz, Víctor Hontañón, Silvia García-Bujalance, Milagros García López-Hortelano, Alicia González-Baeza, María Luz Martín-Carbonero, Mario Mayoral, María José Mellado, Rafael Esteban Micán, Rocío Montejano, María Luisa Montes, Victoria Moreno, Ignacio Pérez-Valero, Guadalupe Rúa Cebrián, Berta Rodés, Talia Sainz, Elena Sendagorta, Natalia Stella Alcáriz, Eulalia Valencia.

- •

Hospital San Pedro [San Pedro Hospital] Centro de Investigación Biomédica de La Rioja [La Rioja Biomedical Research Centre] (CIBIR) (Logroño)

José Ramón Blanco, José Antonio Oteo, Valvanera Ibarra, Luis Metola, Mercedes Sanz, Laura Pérez-Martínez.

- •

Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet [Miguel Servet University Hospital] (Zaragoza)

Piedad Arazo, Gloria Sampériz.

- •

Hospital Universitari MútuaTerrassa [MútuaTerrassa University Hospital] (Terrassa)

David Dalmau, Àngels Jaén, Montse Sanmartí, Mireia Cairó, Javier Martínez-Lacasa, Pablo Velli, Roser Font, Marina Martínez, Francesco Aiello

- •

Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra [Navarra Hospital Complex] (Pamplona)

María Rivero Marcotegui, Jesús Repáraz, María Gracia Ruiz de Alda, María Teresa de León Cano, Beatriz Pierola Ruiz de Galarreta.

- •

Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí [Parc Taulí Health Corporation] (Sabadell)

María José Amengual, Gemma Navarro, Manel Cervantes Garcia, Sonia Calzado Isbert, Marta Navarro Vilasaro.

- •

Hospital Universitario de La Princesa [La Princesa University Hospital] (Madrid)

Ignacio de los Santos, Jesús Sanz Sanz, Ana Salas Aparicio, Cristina Sarria Cepeda, Lucio García-Fraile Fraile, Enrique Martín Gayo.

- •

Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal [Ramón y Cajal University Hospital] (Madrid)

Santiago Moreno, José Luis Casado Osorio, Fernando Dronda Nuñez, Ana Moreno Zamora, María Jesús Pérez Elías, Carolina Gutiérrez, Nadia Madrid, Santos del Campo Terrón, Sergio Serrano Villar, María Jesús Vivancos Gallego, Javier Martínez Sanz, Usua Anxa Urroz, Tamara Velasco.

- •

Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía [Reina Sofía University General Hospital] (Murcia)

Enrique Bernal, Alfredo Cano Sanchez, Antonia Alcaraz García, Joaquín Bravo Urbieta, Ángeles Muñoz Perez, María José Alcaraz, María del Carmen Villalba.

- •

Hospital Nuevo San Cecilio [San Cecilio New Hospital] (Granada)

Federico García, José Hernández Quero, Leopoldo Muñoz Medina, Marta Álvarez, Natalia Chueca, David Vinuesa García, Clara Martínez-Montes, Carlos Guerrero Beltrán, Adolfo de Salazar González, Ana Fuentes López.

- •

Centro Sanitario Sandoval [Sandoval Health Centre] (Madrid)

Jorge del Romero, Montserrat Raposo Utrilla, Carmen Rodríguez, Teresa Puerta, Juan Carlos Carrió, Mar Vera, Juan Ballesteros, Oskar Ayerdi.

- •

Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago [Santiago University Clinical Hospital] (Santiago de Compostela)

Antonio Antela, Elena Losada.

- •

Hospital Universitario Son Espases [Son Espases University Hospital] (Palma de Mallorca)

Melchor Riera, María Peñaranda, M. Àngels Ribas, Antoni A. Campins, Carmen Vidal, Francisco Fanjul, Javier Murillas, Francisco Homar, Helem H. Vilchez, María Luisa Martín, Antoni Payeras.

- •

Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria [Virgen de la Victoria University Hospital] (Malaga)

Jesús Santos, Cristina Gómez Ayerbe, Isabel Viciana, Rosario Palacios, Carmen Pérez López, Carmen María Gonzalez-Domenec.

- •

Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío [Virgen del Rocío University Hospital] (Seville)

Pompeyo Viciana, Nuria Espinosa, Luis Fernando López-Cortés.

- •

Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge [Bellvitge University Hospital] (Hospitalet de Llobregat)

Daniel Podzamczer, Arkaitz Imaz, Juan Tiraboschi, Ana Silva, María Saumoy, Paula Prieto.

- •

Hospital Universitario Vall d'Hebron [Vall d'Hebron University Hospital] (Barcelona)

Esteban Ribera, Adrián Curran.

- •

Hospital Costa del Sol [Costa del Sol Hospital] (Marbella)

Julián Olalla Sierra, Javier Pérez Stachowski, Alfonso del Arco, Javier de la Torre, José Luis Prada, José María García de Lomas Guerrero.

- •

Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía [Santa Lucía University Hospital] (Cartagena)

Onofre Juan Martínez, Francisco Jesús Vera, Lorena Martínez, Josefina García, Begoña Alcaraz, Amaya Jimeno.

- •

Complejo Hospitalario Universitario a Coruña [A Coruña University Hospital Complex] (CHUAC) (A Coruña)

Ángeles Castro Iglesias, Berta Pernas Souto, Álvaro Mena de Cea.

- •

Hospital Universitario Basurto [Basurto University Hospital] (Bilbao)

Josefa Muñoz, Miren Zuriñe Zubero, Josu Mirena Baraia-Etxaburu, Sofía Ibarra Ugarte, Oscar Luis Ferrero Beneitez, Josefina López de Munain, M. Mar Cámara López, Mireia de la Peña, Miriam López, Iñigo Lopez Azkarreta.

- •

Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca [Virgen de la Arrixaca University Hospital] (El Palmar)

Carlos Galera, Helena Albendin, Aurora Pérez, Asunción Iborra, Antonio Moreno, María Angustias Merlos, Asunción Vidal, Marisa Meca.

- •

Hospital de la Marina Baixa [Marina Baixa Hospital] (La Vila Joiosa)

Concha Amador, Francisco Pasquau, Javier Ena, Concha Benito, Vicenta Fenoll, Concepción Gil Anguita, José Tomás Algado Rabasa.

- •

Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía [Infanta Sofía University Hospital] (San Sebastián de los Reyes)

Inés Suárez-García, Eduardo Malmierca, Patricia González-Ruano, Dolores Martín Rodrigo, M. Pilar Ruiz Seco.

- •

Hospital Universitario de Jaén [Jaén University Hospital] (Jaén)

Mohamed Omar Mohamed-Balghata, María Amparo Gómez Vidal.

- •

Hospital San Agustín [San Agustín Hospital] (Avilés)

Miguel Alberto de Zarraga.

- •

Hospital Clínico San Carlos [San Carlos Clinical Hospital] (Madrid)

Vicente Estrada Pérez, María Jesús Téllez Molina, Jorge Vergas García, Juncal Pérez-Somarriba Moreno.

- •

Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz [Jiménez Díaz Foundation University Hospital] (Madrid)

Miguel Górgolas, Alfonso Cabello, Beatriz Álvarez, Laura Prieto.

- •

Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias [Príncipe de Asturias University Hospital] (Alcalá de Henares)

José Sanz Moreno, Alberto Arranz Caso, Cristina Hernández Gutiérrez, María Novella Mena.

- •

Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia [Valencia University Clinical Hospital] (Valencia)

María José Galindo Puerto, Ramón Fernando Vilalta, Ana Ferrer Ribera.

- •

Hospital Reina Sofía [Reina Sofía Hospital] (Córdoba)

Antonio Rivero Román, Antonio Rivero Juárez, Pedro López, Isabel Machuca Sánchez, Mario Frias Casas, Angela Camacho Espejo.

- •

Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa [Severo Ochoa University Hospital] (Leganés)

Miguel Cervero Jiménez, Rafael Torres Perea.

- •

Nuestra Señora de Valme (Seville)

Juan A. Pineda, Pilar Rincón Mayo, Juan Macías Sanchez, Nicolás Merchante Gutiérrez, Luis Miguel Real, Anais Corma Gomez, Marta Fernández Fuertes, Alejandro Gonzalez-Serna.

- •

Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro [Álvaro Cunqueiro Hospital] (Vigo)

Eva Poveda, Alexandre Pérez, Manuel Crespo, Luis Morano, Celia Miralles, Antonio Ocampo, Guillermo Pousada.

Please cite this article as: Muñoz Hornero C, Muriel A, Montero M, Iribarren JA, Masía M, Muñoz L, et al. Diferencias epidemiológicas y de mortalidad entre hombres y mujeres con infección por VIH en la cohorte CoRIS entre los años 2004 y 2014. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:372–382.