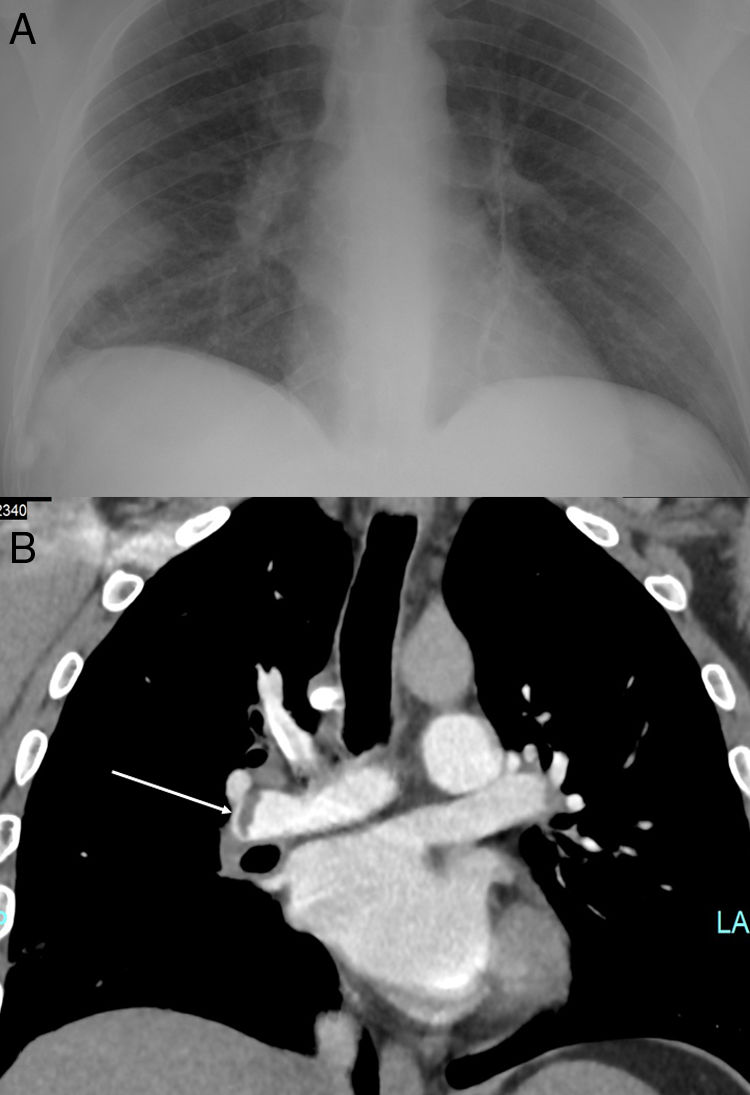

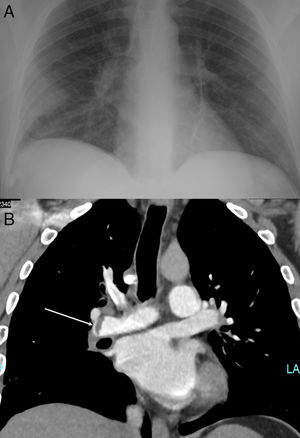

A 45-year-old man, active smoker and intranasal cocaine user, presented to the emergency department with a 5-day history of general discomfort, dyspnea and pleuritic chest pain. He reported hemoptysis in the last 24h. On physical examination, the patient was afebrile, his blood pressure was 110/60mmHg, the heart rate 60 beats per minute, and the oxygen saturation 94% while breathing room air. Laboratory tests showed a C-reactive protein of 18.7mg per liter, a D-dimer of 3.58μg per milliliter, 12,480 leukocytes per microliter and 1200 lymphocytes per microliter. The arterial blood gas test showed hypoxemia with an arterial oxygen pressure of 67.8mmHg while breathing room air. A chest radiography was performed showing a pleural-dependent cuneiform opacity at the right lower lobe (Fig. 1A).

A polymerase chain reaction test for SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs was positive. Computerized tomography (CT) angiography (Fig. 1B) confirmed the presence of pulmonary thromboembolism at the right pulmonary artery, and a pulmonary infiltrate on the right lower lobe indicative of pulmonary infarction. The opacity on the chest X-ray was suggestive of Hampton's hump. The patient had been diagnosed 8 days before at the emergency department of deep vein thrombosis in the femoral, popliteal, posterior tibial and external saphenous veins. He had no symptoms suggesting infection with SARS-CoV-2, and the chest X-ray and electrocardiogram had been normal, so he was discharged with oral anticoagulation.

EvolutionTreatment was initiated with low molecular weight heparin at a dose of 1mg per kilogram every 12h, hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin and lopinavir/ritonavir. The patient had a satisfactory clinical outcome, and on day 7 he reported complete resolution of the pulmonary symptoms, and his blood oxygen saturation while breathing room air was 98%.

CommentsThis patient had deep venous thrombosis as the first manifestation of COVID-19. The incidence of thrombosis might be increased in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV)-2 disease (COVID-19).1 In SARS outbreak occurred in 2003, an incidence of deep vein thrombosis up to 20.5% and of pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) of 11.3% were reported.2 COVID-19 has been associated with elevated levels of D-dimer, which have been linked with severe disease, clinical progression, and poor prognosis.3,4 In a case series of 107 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), the cumulative incidence of PTE was 20%, twice higher than the frequency of historical ICU controls.1 PTE has also been reported after initial improvement, during the recovery phase after the cytokine storm5 but, to the best of our knowledge, it had not been described as the initial manifestation leading to the diagnosis of COVID-19. Most of previous cases of venous thromboembolism have been reported in severe patients, when the cytochemical storm syndrome has developed.6,7 Some of the mechanisms potentially contributing to explain the higher risk of thromboembolic complications observed in severe forms of COVID-19 are local inflammation, hemodynamic changes, and the induction of procoagulant factors driven by the enhanced systemic pro-inflammatory response.3 Vascular endothelial injury leading to disseminated intravascular coagulation has also been proposed as a potential subjacent mechanism involved in the state of hypercoagulability, based on autopsy findings showing microthrombi in the lungs.8

This case in a patient without apparent predisposing factors highlights the importance of maintaining the suspicion of COVID-19 disease during the pandemic in the presence of non-typical initial clinical manifestations, especially in those with underlying thrombotic phenomena, and encourages to deepen into the underlying pathophysiological mechanism involved in COVID-19-related coagulopathy.

Conflict of interestNo conflict of interest.