Ecthyma gangrenosum is an uncommon skin manifestation of systemic infection that generally affects immunocompromised patients.1

We present the case of a 63-year-old female patient with a history of acute myeloid leukaemia on active treatment with carboplatin and etoposide after progressing from first-line and second-line treatment (idarubicin-cytarabine and the FLAG-IDA regimen: fludarabine + cytarabine and idarubicin and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor).

On day +7 of the first cycle, the patient experienced an episode of fever, coughing and dyspnoea, as well as pancytopaenia. She was admitted to hospital and administered broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy with piperacillin/tazobactam in combination with amikacin and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor. Complementary tests were also performed.

The pulmonary auscultation performed on physical examination revealed decreased breath sounds and scattered rhonchi.

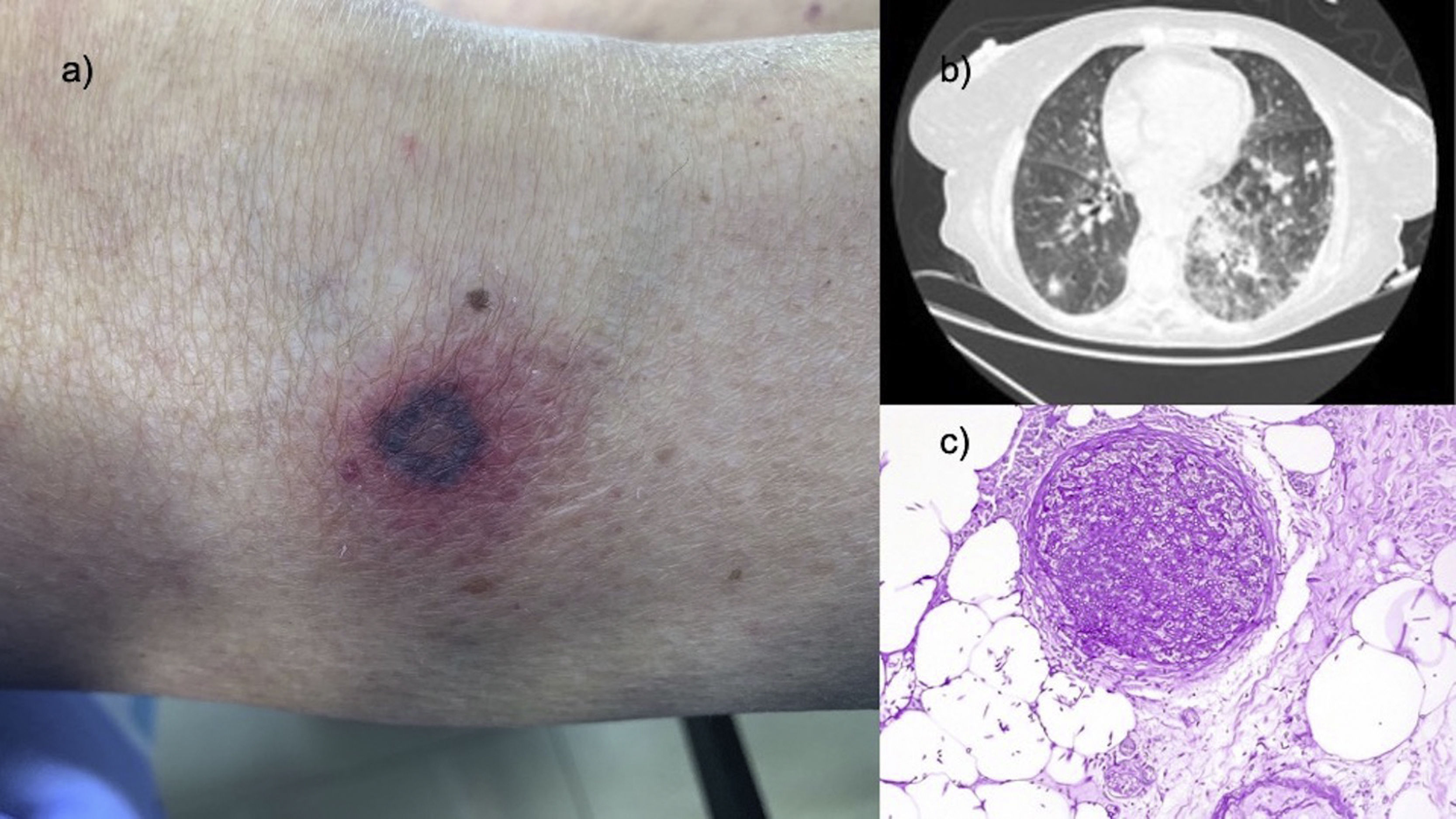

An erythematous macule measuring 8 × 12 mm with a necrotic annular centre was observed on the outer part of the patient's right knee (Fig. 1a).

a) Photograph of the lesion located on the outer region of the right knee. b) Chest CT image with pulmonary window showing the bilateral 'cobblestone' pattern and several nodules. c) Haematoxylin-eosin ×40: medium-sized vessel completely blocked by a thrombus of fungal structures.

The complementary tests performed are described below.

A chest CT scan was conducted, which showed diffuse alteration of the pulmonary parenchyma with bilateral 'cobblestone' pattern and multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules with surrounding halo of ground-glass attenuation and area of left perihilar consolidation (Fig. 1b).

The bronchoscopy showed thickening of the left bronchial tree and erythaema of the mucosa at the entrance to the lung base that prevented the passage of the bronchoscope. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed, finding no malignant cells.

The skin biopsy of the lesion identified fungal structures (spores and hyphae) in the connective tissue of the skin and subcutaneous cellular tissue, as well as in the vessels of the superficial and reticular dermis and of the subcutaneous cellular tissue. Intravascular thrombi were also observed in many of the small and medium-sized blood vessels (Fig. 1c).

The skin biopsy culture revealed growth of Fusarium proliferatum.

Two of the four blood cultures were positive for Fusarium proliferatum.

Despite changing the patient's antibiotic therapy and starting a loading dose of intravenous voriconazole 200 mg every 12 h, she died a week after the onset of symptoms.

Ecthyma gangrenosum has often been associated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa,1 although on rare occasions it is caused by other infectious pathogens. The literature points to a broader bacterial spectrum with Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Citrobacter freundii, Klebsiella pneumonia and Morganella morganii. Moreover, some fungi, such as species of Candida, Aspergillus and Curvularia, have been reported to cause clinically similar lesions.2

Some authors define the disease according to its aetiological agent, while others define it by its clinical characteristics. However, the name attributed to the disease rarely reflects a fungal infection. This confusion may mask a much broader prevalence of ecthyma gangrenosum-like infections that might otherwise have been reported in a broad spectrum of fungal diseases.

The species Fusarium is an opportunistic fungal pathogen that causes disseminated infections in immunocompromised patients.

Given the high mortality rate associated with this infection, making a definitive diagnosis in suspected cases is important. Skin involvement is the first sign of disseminated fusarium infection in most cases, and it often manifests early in the disease. Multiple painful papular or macular erythematous lesions are reported in 70% of cases. The lesions tend to have a necrotic centre similar to ecthyma gangrenosum and are described as ecthyma gangrenosum-like lesions.3

In immunocompromised patients, fusarium infection often spreads and is usually accompanied by lung involvement, resulting in a high mortality rate that can exceed 50%.4

That is why detecting each individual skin lesion in patients with haematological malignancies and pancytopaenia, performing a skin biopsy and administering antibiotics and antifungals early, together with neutrophil-stimulating factors for rapid recovery, is absolutely vital.

In conclusion, this is one of the few documented cases in the literature of an ecthyma gangrenosum-like lesion caused by Fusarium proliferatum. We stress the need to conduct a dermatological examination in these patients and the importance of an early skin biopsy of any lesion in order to make a correct diagnosis and initiate treatment as early as possible.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz-Sanchez D, Valtueña J, Garabito Solovera E, Martinez Garcia G. Ectima gangrenoso, más allá de Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:526–527.