We assessed poor linkage to HIV care in a sample of HIV positive men who have sex with men (MSM) diagnosed in Spain.

MethodsFrom 2012 to 2013 we recruited a sample of MSM mainly through gay-dating websites. Poor linkage to care was defined as receiving the first CD4 count >3 months after HIV diagnosis. We performed a logistic regression analysis to estimate factors associated with poor linkage to care and analyzed the underlying reasons.

ResultsSome 9.4% self-reported poor linkage to care. Those diagnosed in clinical settings other than sexual health clinics or in non-clinical settings presented increased odds of poor linkage to care. The most common reason was being assigned an appointment for first CD4 count >3 months after initial HIV diagnosis.

ConclusionPoor linkage to care was very low, but for further improvements fast-track referral pathways should be created, especially in contexts outside sexual health clinics.

Analizamos la incorrecta vinculación al seguimiento médico de la infección por VIH en una muestra de hombres que tienen sexo con hombres (HSH) diagnosticados en España.

MétodosDurante 2012 y 2013 se reclutó una muestra de HSH principalmente en páginas de contactos gais. Se definió vinculación incorrecta al seguimiento a haber recibido el primer recuento de CD4>3 meses después del diagnóstico de VIH. Realizamos un análisis de regresión logística para estimar los factores asociados a una incorrecta vinculación y analizamos las razones subyacentes.

ResultadosUn 9,4% refirió incorrecta vinculación al seguimiento. Los diagnosticados en contextos clínicos que no eran clínicas de infecciones de transmisión sexual (ITS) y aquellos diagnosticados en entornos no clínicos presentaron un mayor riesgo de referir una incorrecta vinculación. La razón más frecuente fue que la cita para el primer recuento de CD4 se concedió para >3 meses después del diagnóstico de VIH.

ConclusiónLa incorrecta vinculación al cuidado es muy baja y para un rendimiento incluso mejor se deberán crear cauces de derivación más rápidos especialmente en contextos más allá de las clínicas de ITS.

HIV diagnosis must be followed by timely entry to care as linkage delays are associated with higher probabilities of progression to AIDS and pose a greater risk of ongoing transmission.1

In Western Europe2 linkage to care is especially good among men who have sex with men (MSM). However, given that they are disproportionately affected by HIV, the highest absolute numbers of poorly linked to care individuals are seen in this group.

As of today, there are still some questions that need to be answered if we want to further improve linkage to care in this population. Thus, we do not know which subgroups of MSM are more affected by delays of this nature. Additionally, the role of the setting of HIV diagnosis in linkage delays has never been studies in Europe. Finally, research on barriers that complicate linkage to HIV specialist care is extremely scarce. In Western Europe, it has been carried out in the United Kingdom (UK) and has focused on African communities.3,4

With this in mind, our aim is to assess the factors associated to poor linkage to care among an online recruited sample of MSM diagnosed with HIV in Spain and to assess the reasons why linkage to care did not occur during the first three months before initial diagnosis.

MethodsWe conducted an online study from September 2012 to February 2013 to recruit MSM mainly through gay dating websites. Recruitment procedures are described elsewhere.5

We included MSM of ≥18 years of age with data on date of initial HIV diagnosis and first CD4 count. We restricted our sample to 672 individuals who self-reported being HIV positive and having received their diagnosis in Spain between 3 and 24 months since the day they completed the questionnaire.

Poor linkage to care was defined as having a CD4 count >3 months after being newly diagnosed with HIV or not having received the result of the first CD4 count in the moment of study participation.

Statistical analysisWe carried out a descriptive analysis by linkage to care status. Differences were assessed using the chi-square test for proportions.

The factors associated with poor linkage to care were first analyzed by bivariate analysis. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated to determine the magnitude and precision of associations. Multivariate logistic regression was then performed following the methodology of Hosmer and Lemeshow.6 The likelihood ratio test was used to evaluate the contribution of each variable to the model.

For those who reported poor linkage to care, we analyzed the reasons by time taken to be linked to care: 3–6 months; >6 months. The latter category also included those diagnosed more than 6 months ago and that have yet to receive a CD4 count at the moment of participation in the study.

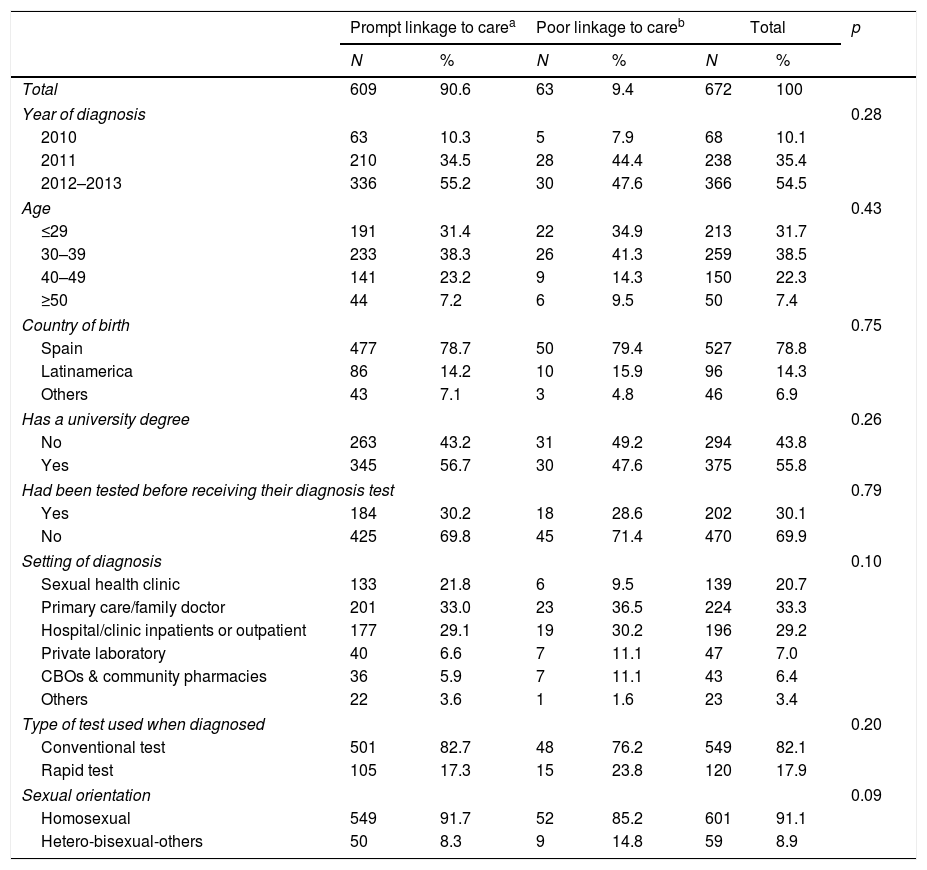

ResultsOverall, 9.4% of the 672 HIV positive MSM were classified in the poor linkage to care category (Table 1).

Main characteristics of HIV positive MSM by linkage to care status (n=672).

| Prompt linkage to carea | Poor linkage to careb | Total | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Total | 609 | 90.6 | 63 | 9.4 | 672 | 100 | |

| Year of diagnosis | 0.28 | ||||||

| 2010 | 63 | 10.3 | 5 | 7.9 | 68 | 10.1 | |

| 2011 | 210 | 34.5 | 28 | 44.4 | 238 | 35.4 | |

| 2012–2013 | 336 | 55.2 | 30 | 47.6 | 366 | 54.5 | |

| Age | 0.43 | ||||||

| ≤29 | 191 | 31.4 | 22 | 34.9 | 213 | 31.7 | |

| 30–39 | 233 | 38.3 | 26 | 41.3 | 259 | 38.5 | |

| 40–49 | 141 | 23.2 | 9 | 14.3 | 150 | 22.3 | |

| ≥50 | 44 | 7.2 | 6 | 9.5 | 50 | 7.4 | |

| Country of birth | 0.75 | ||||||

| Spain | 477 | 78.7 | 50 | 79.4 | 527 | 78.8 | |

| Latinamerica | 86 | 14.2 | 10 | 15.9 | 96 | 14.3 | |

| Others | 43 | 7.1 | 3 | 4.8 | 46 | 6.9 | |

| Has a university degree | 0.26 | ||||||

| No | 263 | 43.2 | 31 | 49.2 | 294 | 43.8 | |

| Yes | 345 | 56.7 | 30 | 47.6 | 375 | 55.8 | |

| Had been tested before receiving their diagnosis test | 0.79 | ||||||

| Yes | 184 | 30.2 | 18 | 28.6 | 202 | 30.1 | |

| No | 425 | 69.8 | 45 | 71.4 | 470 | 69.9 | |

| Setting of diagnosis | 0.10 | ||||||

| Sexual health clinic | 133 | 21.8 | 6 | 9.5 | 139 | 20.7 | |

| Primary care/family doctor | 201 | 33.0 | 23 | 36.5 | 224 | 33.3 | |

| Hospital/clinic inpatients or outpatient | 177 | 29.1 | 19 | 30.2 | 196 | 29.2 | |

| Private laboratory | 40 | 6.6 | 7 | 11.1 | 47 | 7.0 | |

| CBOs & community pharmacies | 36 | 5.9 | 7 | 11.1 | 43 | 6.4 | |

| Others | 22 | 3.6 | 1 | 1.6 | 23 | 3.4 | |

| Type of test used when diagnosed | 0.20 | ||||||

| Conventional test | 501 | 82.7 | 48 | 76.2 | 549 | 82.1 | |

| Rapid test | 105 | 17.3 | 15 | 23.8 | 120 | 17.9 | |

| Sexual orientation | 0.09 | ||||||

| Homosexual | 549 | 91.7 | 52 | 85.2 | 601 | 91.1 | |

| Hetero-bisexual-others | 50 | 8.3 | 9 | 14.8 | 59 | 8.9 | |

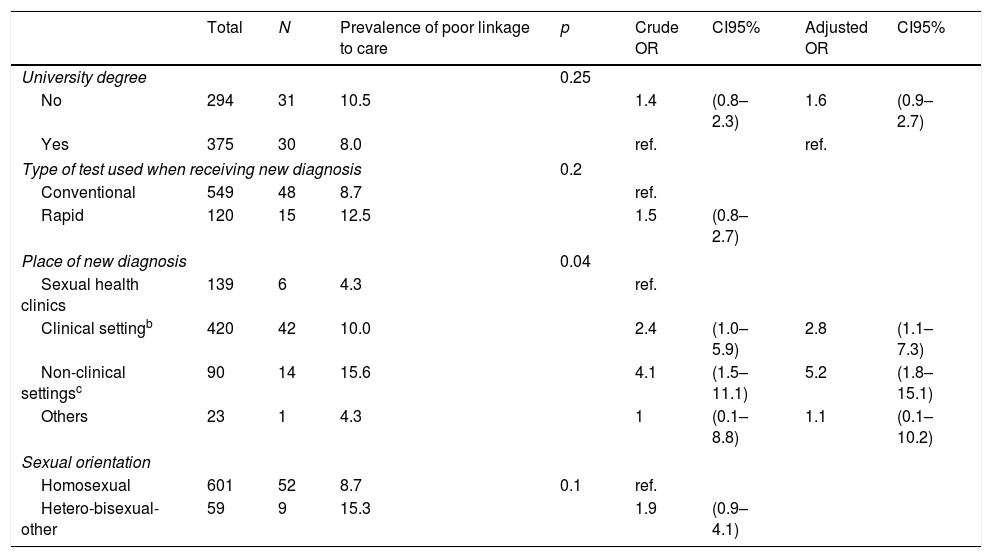

Multivariate analysis showed that having received an HIV diagnosis outside a clinical setting (OR 5.2; CI95% (1.8–15.1)) or in a clinical setting other than a sexual health clinic (OR 2.8; CI95% (1.1–7.3)) were associated with reporting poor linkage to care (Table 2).

Prevalence and factors associated with poor linkage to carea (N=672).

| Total | N | Prevalence of poor linkage to care | p | Crude OR | CI95% | Adjusted OR | CI95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University degree | 0.25 | |||||||

| No | 294 | 31 | 10.5 | 1.4 | (0.8–2.3) | 1.6 | (0.9–2.7) | |

| Yes | 375 | 30 | 8.0 | ref. | ref. | |||

| Type of test used when receiving new diagnosis | 0.2 | |||||||

| Conventional | 549 | 48 | 8.7 | ref. | ||||

| Rapid | 120 | 15 | 12.5 | 1.5 | (0.8–2.7) | |||

| Place of new diagnosis | 0.04 | |||||||

| Sexual health clinics | 139 | 6 | 4.3 | ref. | ||||

| Clinical settingb | 420 | 42 | 10.0 | 2.4 | (1.0–5.9) | 2.8 | (1.1–7.3) | |

| Non-clinical settingsc | 90 | 14 | 15.6 | 4.1 | (1.5–11.1) | 5.2 | (1.8–15.1) | |

| Others | 23 | 1 | 4.3 | 1 | (0.1–8.8) | 1.1 | (0.1–10.2) | |

| Sexual orientation | ||||||||

| Homosexual | 601 | 52 | 8.7 | 0.1 | ref. | |||

| Hetero-bisexual-other | 59 | 9 | 15.3 | 1.9 | (0.9–4.1) | |||

Poor linkage to care: having a CD4 count more than 3 months after being newly diagnosed with HIV.

Having received an appointment more than 3 months after receiving the diagnosis of HIV was the most commonly reported reason for suboptimal linkage to care (49.2%) and was notably higher among those linked to care 3–6 months after initial HIV diagnosis (70.3%) than among those linked to care >6 months after (13.6%). On the other hand, reasons related to denial were reported by 16.9% of the participants and were especially prevalent among those linked more than 6 months ago (40.9%).

DiscussionPoor linkage to care among MSM diagnosed in Spain was very low. Only those diagnosed in clinical settings other than sexual health clinics or in non-clinical settings had increased odds of poor linkage to care. Almost half of the respondents self-reported that the main reason for poor linkage to care was having received an appointment >3 months away from diagnosis.

We found that poor linkage to care was similar to that reported in Italy (7.9%) and Australia (9.1%) and lower to the one from the US (20.2%) and Canada (27.4%).7 All four figures pertain to a multi-country study that used a criteria to define poor linkage to care similar to ours: ≥1 CD4 count or Viral Load within 3 months of diagnosis. Another study conducted in a sexual health clinic from the Netherlands also found a higher prevalence of delayed linkage to care among their MSM patients (30.5%)8 although the cut-off point used to define poor linkage to care in this study was different to ours (>4 weeks).

In Spain, a study conducted at a community based organization, observed that 85.0%9 of the MSM receiving a reactive rapid test result were linked to care. However, their definition was based on HIV unit referral (vs. CD4 count) within one month after initial diagnosis (vs. 3 months). If we compare our results to previous estimates that used data from the Spanish HIV surveillance system,10 poor linkage to care is lower (9.4% vs. 19.6%). In this study, the definition for poor linkage to care was the same as ours and the difference could be explained by the linkage to care estimation method as authors used data from all individuals, including those with missing data on CD4 count. A fraction of those with missing data could actually be linked to care. In this sense, missing data could be a product not so much of non-linkage to care but of suboptimal data collection. In our study, we only analyzed those of whom we knew their linkage to care status.

None of the sociodemographic or behavioural variables we analyzed had an impact on linkage to care. The only variable that had an influence was the setting of reception of HIV diagnosis which mirrors the results of a study conducted in the US.11 Compared to Sexual health clinics, lower linkage to care was observed in clinical settings not specialized in HIV care and – especially – in non-clinical settings. Clinical settings not specialized in HIV care do not manage HIV cases as often as Sexual health clinics who probably have clear protocols and established pathways to manage newly diagnosed individuals. Non-clinical settings are not part of the health system. Taking testing outside of clinical settings has a number of benefits but linkage to care is one of the main challenges this strategy faces.12

Our analysis suggests that barriers are mainly related with the appointment system. This reason was especially prevalent among those who were linked to care between 3 and 6 months following diagnosis. Close cooperation with the confirmation site is vital to shorten linkage times. If possible, offering accompaniment for the first visit to the HIV unit could also result in quicker linkage.12 On those more severely affected by poor linkage to care (>6 months) there appears to be a subgroup for whom the main reasons are related to denial. For this group, several case management interventions have proven to be effective.13,14

Results are not without limitations. Definitions for linkage to care are very diverse, making it difficult to contextualize our results within the existing literature.15 The self-reported nature could influence the accuracy of our results and memory bias could be present in the responses given to the questions that assessed the time since first HIV diagnosis and the first CD4 count. To limit its influence, we decided to cap our analysis to individuals who were diagnosed with HIV in the 24 months preceding their participation in the study.

Poor linkage to care was very low, highlighting a very good performance of the Spanish health system in quickly engaging newly diagnosed individuals into HIV care. For further improvement, efforts should be placed in optimizing referral pathways between settings other than sexual health clinics and specialist care.

FundingWriting the paper was partially supported by “Ayuda Juan de la Cierva-Incorporación” (grant number IJCI-2015-23261). The funding source was not involved in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation data; in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conflict of interestNone.