To analyze the determinants that influence the health-related quality of life of people living with HIV in Alicante (Spain).

MethodsA cross-sectional study was conducted, which recruited 214 Spanish-speaking participants over 18 years of age living with HIV from an outpatient consulting office of the infectious diseases in a hospital in Alicante between 2013 and 2014. A self-administration sociodemographic survey and the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36v2) was used to assess health-related quality of life. This questionnaire measures health on eight domains.

Results70% of the participants were male, 50% had CD4 cell count between 200−499 cells/mm3 and 20% were infected by the hepatitis C virus (HCV). For the eight SF-36v2 scales, the average scores were higher than 45. Men presented better scores than women; there were statistically significant differences in all the scales except for general health. Being co-infected with HCV and being unemployed or other situations other than having a job were significantly associated with a lower physical component summary (PCS), while being married or having a partner were significantly associated with a higher score in the mental component summary (MCS).

ConclusionThe socioeconomic level and the presence of clinical factors such as HCV influence the scales of quality of life of physical health among adults living with HIV.

Analizar los determinantes que influyen en la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud de las personas que viven con el VIH en Alicante (España).

MétodosSe realizó un estudio descriptivo transversal que reclutó a 214 participantes castellanoparlantes mayores de 18 años con VIH atendidos en consultas externas de la Unidad de Enfermedades Infecciosas de un hospital de Alicante entre 2013 y 2014. Se auto-administró un cuestionario sociodemográfico y el cuestionario sobre calidad de vida relacionado con la salud Short-Form-36 (SF-36v2) que mide la salud en ocho dimensiones.

ResultadosEl 70% de los entrevistados eran varones, el 50% presentaban cifras de linfocitos CD4+ entre200 a 499cel/mm3. El 20% estaban coinfectados por el virus de la Hepatitis C (VHC). Para las ocho dimensiones del SF-36v2, las puntuaciones medias fueron superiores a 45. Los hombres presentaron mejores puntuaciones que las mujeres en todas las dimensiones a excepción de la salud general, siendo estadísticamente significativos. La coinfección con VHC y una peor situación laboral resultó con una menor puntuación en el Componente Sumario Físico (CSF), mientras que estar casado o tener pareja se asoció significativamente con una mayor puntación en el Componente Sumario Mental (CSM).

ConclusiónEl nivel socioeconómico y la presencia de factores clínicos como la coinfección por el VHC influyen en las dimensiones de calidad de vida de la salud física en los adultos que viven con VIH.

In Spain, rates of new diagnoses of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are higher than the average of countries in the European Union and Western Europe. HIV is estimated to affect close to 145,000 people in Spain.1 In 2018 alone, 3244 new diagnoses were reported. This represents an annual estimated rate of new HIV infections of 8.65 per 100,000 inhabitants, while the rate of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) was 1.4/100,000 in the same period. New cases of AIDS have been decreasing since the mid-1990s, with the advent of antiretroviral therapy (ART).2 The efficacy of these treatments and increased access to them has increased survival in people living with HIV (PLWHA) and as a result they live longer.3

Thus, HIV has become a chronic condition. It also remains a global crisis of persistent social precariousness, especially among marginalised populations, and of uncertainty due to ageing, long-term ART toxicity and growing social inequalities.4 Therefore, an important aspect to be considered among PLWHA is health-related quality of life (HRQoL), evaluating their well-being and factors that might influence it. Some factors that have been clearly linked to HRQoL in PLWHA are advanced age, gender, incomplete education and unemployment, while there is a certain amount of debate as to the relationship between HRQoL and other factors such as CD4+ lymphocyte count and viral load.5–8

HRQoL is defined as a subjective outcome measure that evaluates the impact of health status and physical, mental and social functioning in relation to an individual's objectives.9 It can be analysed with different tools, such as the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).10–14 This generic tool offers a comprehensive profile that is efficient and psychometrically sound for measuring health status from the subject's point of view.15 The SF-36 has also been used to evaluate HRQoL in the population with HIV.10–13,16,17 For example, the SF-36 tool was used to explore the link between perceived social support and results for each health dimension in a group of PLWHA cared for in a hospital network in Colombia17 and to evaluate changes in HRQoL in PLWHA a year after starting ART.16

In Spain, comparatively few studies have been conducted assessing HRQoL in PLWHA measured with the SF-36. Data from studies conducted in different Spanish-language contexts cannot be extrapolated due to potential differences in social and healthcare contexts. Therefore, our objective was to analyse the determinants that influence HRQoL in PLWHA in Alicante (Spain) and their association with sociodemographic and clinical variables, measured with the SF-36v2 health questionnaire.

MethodologyDesignAn observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted with PLWHA cared for in the outpatient section of the Infectious Diseases Unit at Hospital General Universitario de Alicante [Alicante University General Hospital] (HGUA) between October 2013 and February 2014.

ParticipantsA total of 214 participants belonging to the Department of Health of the HGUA were enrolled. The inclusion criteria were: patients with a diagnosis of HIV who originated from Spanish-speaking countries, were over the age of 18 and did not have severe cognitive decline. Subjects who did not originate from Spanish-speaking countries were excluded, as the instrument used was validated in Spanish only.18

ProcedureThis study was approved by the HGUA Independent Ethics Committee on 31 October 2012.

Participants were invited to take part in the study during their routine medical visit to the Infectious Diseases Unit. After signing the informed consent form, those who agreed to take part were provided with the sociodemographic questionnaire (which included data on sex, age, marital status, those with whom they lived, level of education, occupational status and sexual orientation) and SF-36v2. Finally, the investigator reviewed the self-completed questionnaire for missing responses.

In addition, medical histories were reviewed to gather data on HIV diagnosis, date of diagnosis, risk behaviours, latest available viral load, nadir, current CD4+ lymphocyte count, ART, year ART was started and current clinical laboratory report on chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

Patients who declined to participate cited lack of time, lack of interest or fear of their condition being disclosed as reasons.

InstrumentTo measure HRQoL, the SF-36v2 health questionnaire was used in its "standard" reminder period (4 weeks).19 The SF-36v2 consists of 36 questions grouped in 8 health domains. Two summary components are derived from these domains: the physical component summary (PCS) and the mental component summary (MCS). Scores of 45 or more are considered average or higher for that health domain.15 The Spanish version of the questionnaire has been shown to be reliable and valid for use in chronic diseases19 such as HIV.20

Statistical analysisReliability for each dimension and for the summary component of the SF-36v2 was evaluated using Cronbach's alpha, a model of internal consistency based on the average of the correlations among the items. In general, a Cronbach's alpha greater than 0.70 is considered acceptable for a psychometric scale.15,18,19,21

A bivariate analysis of the summary components, as well as the different dimensions that comprise them, was performed. The Kruskal–Wallis test or the Mann–Whitney U test was used. In addition, Spearman's correlation coefficient was calculated between the PCS and the MCS.

Two multiple linear regression models were prepared to explain the summary components (PCS and MCS) according to different sociodemographic and clinical factors. The stepwise method was used to construct the models. Compliance with the basic assumptions of the analysis, linearity and normality, was evaluated by inspection of the residual graphs; homoscedasticity of residuals using the Breusch–Pagan test and colinearity using variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance (1/VIF), accepting VIF values lower than 10 and 1/VIF values more than 0.10.

A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analysed using the SPSS v17 statistical software package (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) and Stata v15 (StataCorp LP; College Station, TX, United States).

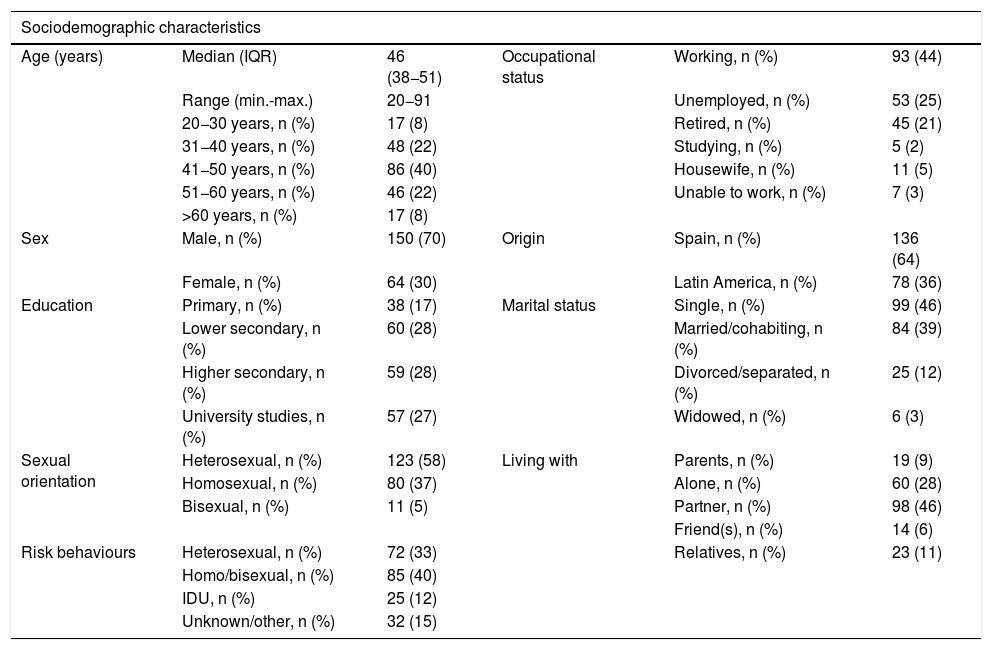

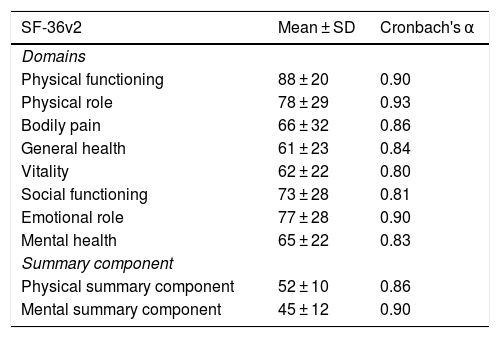

ResultsA total of 214 PLWHA took part in this study. Their characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no missing responses to the questionnaires. Cronbach's alpha coefficient values were more than 0.80 for the 8 domains of the SF-36v2 and greater than or equal to 0.90 for 3 of them (Table 2).

Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of participants (n = 214).

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Median (IQR) | 46 (38−51) | Occupational status | Working, n (%) | 93 (44) |

| Range (min.-max.) | 20−91 | Unemployed, n (%) | 53 (25) | ||

| 20−30 years, n (%) | 17 (8) | Retired, n (%) | 45 (21) | ||

| 31−40 years, n (%) | 48 (22) | Studying, n (%) | 5 (2) | ||

| 41−50 years, n (%) | 86 (40) | Housewife, n (%) | 11 (5) | ||

| 51−60 years, n (%) | 46 (22) | Unable to work, n (%) | 7 (3) | ||

| >60 years, n (%) | 17 (8) | ||||

| Sex | Male, n (%) | 150 (70) | Origin | Spain, n (%) | 136 (64) |

| Female, n (%) | 64 (30) | Latin America, n (%) | 78 (36) | ||

| Education | Primary, n (%) | 38 (17) | Marital status | Single, n (%) | 99 (46) |

| Lower secondary, n (%) | 60 (28) | Married/cohabiting, n (%) | 84 (39) | ||

| Higher secondary, n (%) | 59 (28) | Divorced/separated, n (%) | 25 (12) | ||

| University studies, n (%) | 57 (27) | Widowed, n (%) | 6 (3) | ||

| Sexual orientation | Heterosexual, n (%) | 123 (58) | Living with | Parents, n (%) | 19 (9) |

| Homosexual, n (%) | 80 (37) | Alone, n (%) | 60 (28) | ||

| Bisexual, n (%) | 11 (5) | Partner, n (%) | 98 (46) | ||

| Friend(s), n (%) | 14 (6) | ||||

| Risk behaviours | Heterosexual, n (%) | 72 (33) | Relatives, n (%) | 23 (11) | |

| Homo/bisexual, n (%) | 85 (40) | ||||

| IDU, n (%) | 25 (12) | ||||

| Unknown/other, n (%) | 32 (15) | ||||

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage of HIV infection at diagnosisa | HIV, n (%) | 114 (53) | Co-infection | HBV, n (%) | 9 (4) |

| AIDS, n (%) | 100 (47) | HCV, n (%) | 43 (20) | ||

| CD4+ lymphocyte nadir | <200 cells/mm3, n (%) | 90 (42) | CD4+ lymphocyte count (cells/mm3) | Median (IQR) | 602 (416−748) |

| 200−499 cells/mm3, n (%) | 107 (50) | Range (min.-max.) | 17−1,660 | ||

| ≥500 cells/mm3, n (%) | 17 (8) | <200 cells/mm3, n (%) | 14 (7) | ||

| Years since diagnosis | Median (IQR) | 10 (5−19) | 200−499 cells/mm3, n (%) | 63 (29) | |

| Range (min.-max.) | 0−31 | ≥500 cells/mm3, n (%) | 137 (64) | ||

| ART | Yes, n (%) | 207 (97) | Viral load (copies/mL) | Mean (SD) | 4477 (22,064) |

| No, n (%) | 7 (3) | Range (min.-max.) | 0−192,568 | ||

| Years of treatment | Median (IQR) | 7 (3−16) | <20 copies (ml), n (%) | 169 (79) | |

| Range (min.-max.) | 0−27 | >20 copies (ml), n (%) | 45 (21) | ||

IQR: interquartile range; max.: maximum; min.: minimum; SD: standard deviation.

Scores for the SF-36v2 domains.

| SF-36v2 | Mean ± SD | Cronbach's α |

|---|---|---|

| Domains | ||

| Physical functioning | 88 ± 20 | 0.90 |

| Physical role | 78 ± 29 | 0.93 |

| Bodily pain | 66 ± 32 | 0.86 |

| General health | 61 ± 23 | 0.84 |

| Vitality | 62 ± 22 | 0.80 |

| Social functioning | 73 ± 28 | 0.81 |

| Emotional role | 77 ± 28 | 0.90 |

| Mental health | 65 ± 22 | 0.83 |

| Summary component | ||

| Physical summary component | 52 ± 10 | 0.86 |

| Mental summary component | 45 ± 12 | 0.90 |

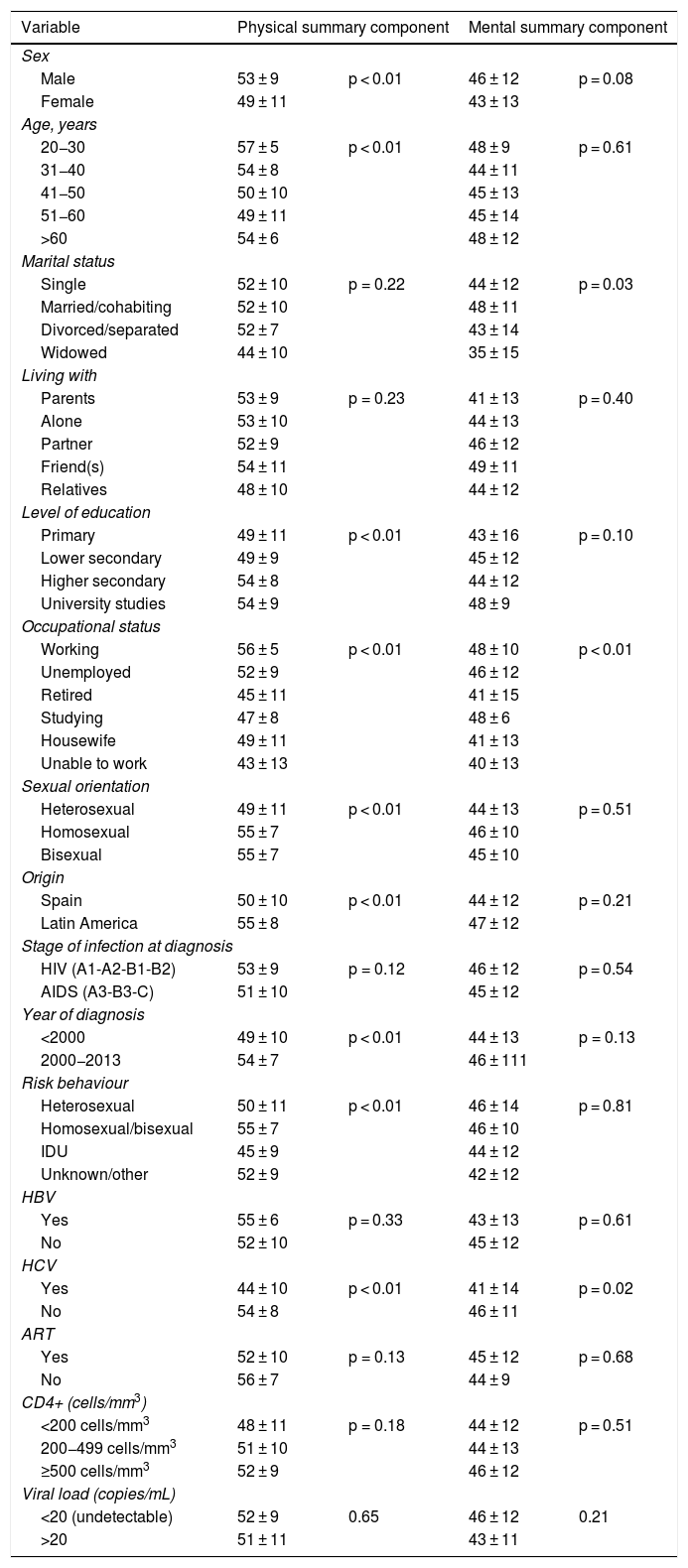

Regarding the PCS, 46 (21%) subjects had scores below values considered normal. Notable among the characteristics that showed differences in the PCS were patient gender and age. The best scores were seen in men and younger patients (20−30 years of age) (Table 3).

Descriptions of the summary components of the SF-36v2, in terms of mean ± standard deviation, for the different sociodemographic and clinical variables (n = 214).

| Variable | Physical summary component | Mental summary component | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 53 ± 9 | p < 0.01 | 46 ± 12 | p = 0.08 |

| Female | 49 ± 11 | 43 ± 13 | ||

| Age, years | ||||

| 20−30 | 57 ± 5 | p < 0.01 | 48 ± 9 | p = 0.61 |

| 31−40 | 54 ± 8 | 44 ± 11 | ||

| 41−50 | 50 ± 10 | 45 ± 13 | ||

| 51−60 | 49 ± 11 | 45 ± 14 | ||

| >60 | 54 ± 6 | 48 ± 12 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 52 ± 10 | p = 0.22 | 44 ± 12 | p = 0.03 |

| Married/cohabiting | 52 ± 10 | 48 ± 11 | ||

| Divorced/separated | 52 ± 7 | 43 ± 14 | ||

| Widowed | 44 ± 10 | 35 ± 15 | ||

| Living with | ||||

| Parents | 53 ± 9 | p = 0.23 | 41 ± 13 | p = 0.40 |

| Alone | 53 ± 10 | 44 ± 13 | ||

| Partner | 52 ± 9 | 46 ± 12 | ||

| Friend(s) | 54 ± 11 | 49 ± 11 | ||

| Relatives | 48 ± 10 | 44 ± 12 | ||

| Level of education | ||||

| Primary | 49 ± 11 | p < 0.01 | 43 ± 16 | p = 0.10 |

| Lower secondary | 49 ± 9 | 45 ± 12 | ||

| Higher secondary | 54 ± 8 | 44 ± 12 | ||

| University studies | 54 ± 9 | 48 ± 9 | ||

| Occupational status | ||||

| Working | 56 ± 5 | p < 0.01 | 48 ± 10 | p < 0.01 |

| Unemployed | 52 ± 9 | 46 ± 12 | ||

| Retired | 45 ± 11 | 41 ± 15 | ||

| Studying | 47 ± 8 | 48 ± 6 | ||

| Housewife | 49 ± 11 | 41 ± 13 | ||

| Unable to work | 43 ± 13 | 40 ± 13 | ||

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Heterosexual | 49 ± 11 | p < 0.01 | 44 ± 13 | p = 0.51 |

| Homosexual | 55 ± 7 | 46 ± 10 | ||

| Bisexual | 55 ± 7 | 45 ± 10 | ||

| Origin | ||||

| Spain | 50 ± 10 | p < 0.01 | 44 ± 12 | p = 0.21 |

| Latin America | 55 ± 8 | 47 ± 12 | ||

| Stage of infection at diagnosis | ||||

| HIV (A1-A2-B1-B2) | 53 ± 9 | p = 0.12 | 46 ± 12 | p = 0.54 |

| AIDS (A3-B3-C) | 51 ± 10 | 45 ± 12 | ||

| Year of diagnosis | ||||

| <2000 | 49 ± 10 | p < 0.01 | 44 ± 13 | p = 0.13 |

| 2000−2013 | 54 ± 7 | 46 ± 111 | ||

| Risk behaviour | ||||

| Heterosexual | 50 ± 11 | p < 0.01 | 46 ± 14 | p = 0.81 |

| Homosexual/bisexual | 55 ± 7 | 46 ± 10 | ||

| IDU | 45 ± 9 | 44 ± 12 | ||

| Unknown/other | 52 ± 9 | 42 ± 12 | ||

| HBV | ||||

| Yes | 55 ± 6 | p = 0.33 | 43 ± 13 | p = 0.61 |

| No | 52 ± 10 | 45 ± 12 | ||

| HCV | ||||

| Yes | 44 ± 10 | p < 0.01 | 41 ± 14 | p = 0.02 |

| No | 54 ± 8 | 46 ± 11 | ||

| ART | ||||

| Yes | 52 ± 10 | p = 0.13 | 45 ± 12 | p = 0.68 |

| No | 56 ± 7 | 44 ± 9 | ||

| CD4+ (cells/mm3) | ||||

| <200 cells/mm3 | 48 ± 11 | p = 0.18 | 44 ± 12 | p = 0.51 |

| 200−499 cells/mm3 | 51 ± 10 | 44 ± 13 | ||

| ≥500 cells/mm3 | 52 ± 9 | 46 ± 12 | ||

| Viral load (copies/mL) | ||||

| <20 (undetectable) | 52 ± 9 | 0.65 | 46 ± 12 | 0.21 |

| >20 | 51 ± 11 | 43 ± 11 | ||

The most significant results obtained on the different dimensions included in the PCS (physical functioning, physical role, bodily pain and general health) are listed below. Data are expressed in terms of mean score and p value [Appendix B, Supplementary Table 1].

For each dimension included in the PCS, men had better scores than women, with statistically significant differences on all dimensions with the exception of general health. The greatest difference in HRQoL between the two sexes was found in mean scores for physical role, with a difference of 13 points. In addition, those with a higher level of education and those who had paid work had a better physical HRQoL score. Moreover, heterosexual (HT) men evaluated their HRQoL as worse compared to homosexual (HM) and bisexual (BS) men, obtaining lower scores for physical functioning (HT = 82, HM = 98, BS = 95; p < 0.01), physical role (HT = 71, HM = 87, BS = 92; p < 0.01) and bodily pain (HT = 60, HM = 74, BS = 75; p < 0.01), whereas for general health the lowest score was for BS men (BS = 53, HT = 57, HM 67 =, p < 0.01).

By place of origin, patients of Spanish (S) origin evaluated their HRQoL as worse than patients of Latin American (L) origin. Differences were observed in the scores for the dimensions of physical functioning (E = 84, L = 94; p < 0.01), physical role (E = 74, L = 85; p = 0.02) and general health (E = 57, L = 67; p = 0.02).

In relation to HRQoL according to clinical variables, patients in the AIDS stage had lower scores in all domains assessed by the SF-36v2 compared to those in earlier stages of the disease, with statistically significant differences in physical functioning (AIDS = 85, HIV = 90; p = 0.05).

It was also found that scores for all domains were lower in patients with concomitant HCV infection, who obtained the lowest values for the domains of bodily pain (HCV = 44, NHCV = 72; p < 0.01) and general health (HCV = 47, NHCV = 64; p < 0.01). Patients with a CD4+ lymphocyte count ≥500 cells/mm3 reported a higher HRQoL on all dimensions of physical health, with a statistically significant difference in general health (63; p = 0.04).

Variables associated with mental healthMCS scores were below normal values in 97 (45%) subjects. Men (M) had better MCS scores, and although the differences were not statistically significant. In women (W), scores were slightly below normal levels (Table 3).

Moreover, each domain of the MCS (Appendix B, Supplementary Table 2) was better valued in men. in men. These included vitality (M = 64, W = 57; p = 0.03), social functioning (SF) (M = 75, W = 67; p = 0.05), emotional role (ER) (M = 77, W = 67, p < 0.01) and mental health (M = 67, W = 61, p = 0.05). Regarding level of education, statistically significant differences were only obtained in SF and ER; patients with university studies showed higher scores (SF = 80, ER = 81), whereas those with basic education obtained the lowest scores (SF = 65, ER = 67). Moreover, those who worked (Wo) or studied (St) had higher scores for vitality (Wo = 69, St = 75), SF (Wo = 81, St = 82) and ER (Wo = 83, St = 75).

In addition, HT men obtained lower scores for SF (p = 0.08) and ER (p = 0.03) compared to HM and BS men. Furthermore, patients of S origin evaluated their HRQoL as worse than patients of L origin on the vitality domain (S = 58; L = 69; p < 0.01).

In relation to HRQoL according to clinical variables, only time since diagnosis and concomitant HCV infection showed significant differences in the mental component. Those without concomitant HCV infection (NHCV) showed higher scores compared to patients with concomitant HCV infection (HCV) for the domains of vitality (NHCV = 65, HCV = 52; p < 0.01), SF (NHCV = 76, HCV = 60; p < 0.01), ER (NHCV = 77, HCV = 61; p < 0.01) and mental health (NHCV = 67, HCV = 57; p < 0.01).

The correlation between the two components (PCS and MCS) was weak (r = 0.251, p < 0.001).

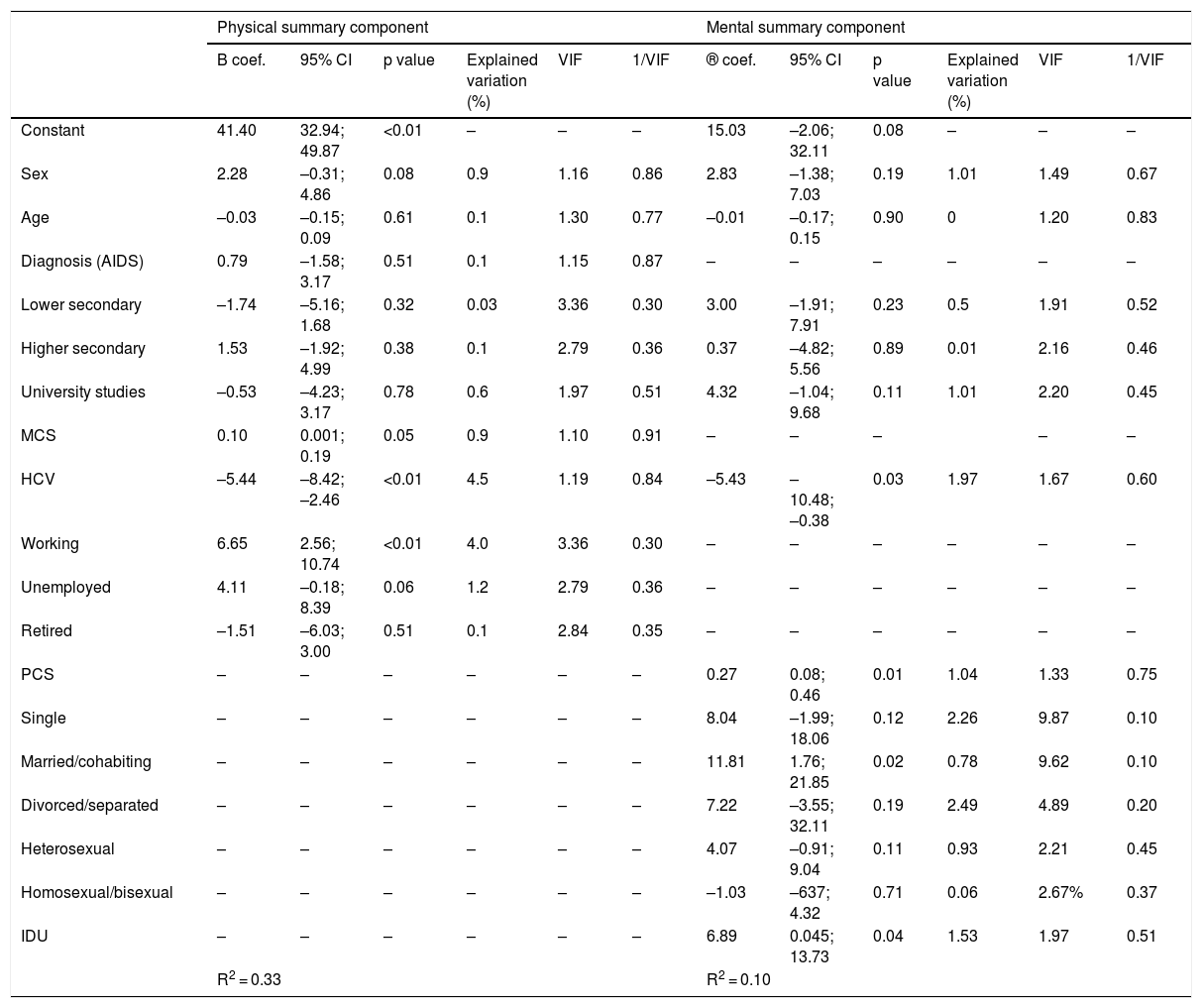

Multivariate analysisThe multiple regression analysis showed that the MCS was significantly associated with a lower score in patients co-infected with HCV and a higher score in those who had paid work. Concomitant HCV infection was also significantly associated with a lower score on the MCS, while being married or having a partner was associated with a higher score. Finally, a higher score on the PCS was associated with a higher score on the MCS and vice versa (Table 4).

Factors that determine the score for the summary components of the SF-36 (multiple linear regression analysis).

| Physical summary component | Mental summary component | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B coef. | 95% CI | p value | Explained variation (%) | VIF | 1/VIF | ® coef. | 95% CI | p value | Explained variation (%) | VIF | 1/VIF | |

| Constant | 41.40 | 32.94; 49.87 | <0.01 | – | – | – | 15.03 | –2.06; 32.11 | 0.08 | – | – | – |

| Sex | 2.28 | –0.31; 4.86 | 0.08 | 0.9 | 1.16 | 0.86 | 2.83 | –1.38; 7.03 | 0.19 | 1.01 | 1.49 | 0.67 |

| Age | –0.03 | –0.15; 0.09 | 0.61 | 0.1 | 1.30 | 0.77 | –0.01 | –0.17; 0.15 | 0.90 | 0 | 1.20 | 0.83 |

| Diagnosis (AIDS) | 0.79 | –1.58; 3.17 | 0.51 | 0.1 | 1.15 | 0.87 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lower secondary | –1.74 | –5.16; 1.68 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 3.36 | 0.30 | 3.00 | –1.91; 7.91 | 0.23 | 0.5 | 1.91 | 0.52 |

| Higher secondary | 1.53 | –1.92; 4.99 | 0.38 | 0.1 | 2.79 | 0.36 | 0.37 | –4.82; 5.56 | 0.89 | 0.01 | 2.16 | 0.46 |

| University studies | –0.53 | –4.23; 3.17 | 0.78 | 0.6 | 1.97 | 0.51 | 4.32 | –1.04; 9.68 | 0.11 | 1.01 | 2.20 | 0.45 |

| MCS | 0.10 | 0.001; 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.9 | 1.10 | 0.91 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| HCV | –5.44 | –8.42; –2.46 | <0.01 | 4.5 | 1.19 | 0.84 | –5.43 | –10.48; –0.38 | 0.03 | 1.97 | 1.67 | 0.60 |

| Working | 6.65 | 2.56; 10.74 | <0.01 | 4.0 | 3.36 | 0.30 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Unemployed | 4.11 | –0.18; 8.39 | 0.06 | 1.2 | 2.79 | 0.36 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Retired | –1.51 | –6.03; 3.00 | 0.51 | 0.1 | 2.84 | 0.35 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| PCS | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.27 | 0.08; 0.46 | 0.01 | 1.04 | 1.33 | 0.75 |

| Single | – | – | – | – | – | – | 8.04 | –1.99; 18.06 | 0.12 | 2.26 | 9.87 | 0.10 |

| Married/cohabiting | – | – | – | – | – | – | 11.81 | 1.76; 21.85 | 0.02 | 0.78 | 9.62 | 0.10 |

| Divorced/separated | – | – | – | – | – | – | 7.22 | –3.55; 32.11 | 0.19 | 2.49 | 4.89 | 0.20 |

| Heterosexual | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4.07 | –0.91; 9.04 | 0.11 | 0.93 | 2.21 | 0.45 |

| Homosexual/bisexual | – | – | – | – | – | – | –1.03 | –637; 4.32 | 0.71 | 0.06 | 2.67% | 0.37 |

| IDU | – | – | – | – | – | – | 6.89 | 0.045; 13.73 | 0.04 | 1.53 | 1.97 | 0.51 |

| R2 = 0.33 | R2 = 0.10 | |||||||||||

®coef.: beta coefficient; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; MCS: mental component summary; PCS: physical component summary; IDU: injecting drug user; VIF: variance inflation factor; 1/VIF: tolerance.

In this study, we used the SF-36v2 generic instrument for evaluating HRQoL in PLWHA. The highest mean score recorded in HRQoL for functional status was in physical functioning 88 (20). This evaluates the degree to which lack of health limits daily activities, such as walking or kneeling. Our findings were similar to those reported in another study conducted in Spain,8 in which this domain was among those with the best scores, as well as a study conducted in Colombia,10 in which PLWHA obtained an average score of 90.29 for this domain. Another study conducted in Portugal showed that both PLWHA and patients with other immune system diseases also had higher scores for physical functioning, with a mean of 69.1.22 The positive assessment of this domain might have derived from the fact that some PLWHA change their lifestyle and adopt healthier attitudes towards exercise as part of coping with their diagnosis and from a desire to continue living.7,23

Moreover, various factors that influence HRQoL assessment in PLWHA have been reported.5–8 Thus, this study assessed both sociodemographic and clinical characteristics that may influence the HRQoL of these patients, which are discussed below.

First, being a woman has been linked to a worse perceived state of health.5,7,8,10,16,24–27 A study conducted in Spain5 found that women report lower scores than men in domains such as bodily pain, physical functioning, mental health and general health. Our data also showed a worse assessment of HRQoL among women. This might have been due to the social norms and expectations associated with gender, where women express their feelings more openly and in greater detail, which would allow them to more readily report their dissatisfaction with their health status. Another factor associated with a worse health status was age. Our patients over 50 years of age had a lower score for their general health, which coincided with the previous literature.6,25

Factors linked to a better HRQoL in PLWHA consist of a higher level of education6,17,25 and paid work.10,16,24,27 In this study, patients with a higher level of education had significantly better scores on the PCS, and those who worked had better scores on both health components compared to those who did not. Some studies, such as one by Briongos Figuero et al.,8 did not find a correlation between level of education, occupation and HRQoL.

Our results also showed that patients who indicated that they were HM/BS perceived themselves to have a better physical health status compared to those who indicated otherwise. By contrast, the literature reflects a certain amount of debate as to the influence of sexual orientation on the assessment of physical functioning. One study associated being HM with a better score for physical functioning,17 whereas another study reported a low score for this functioning in men who have sex with men (MSM).8 In Spain, most new diagnoses of HIV are made in men, especially in MSM, who comprise the group with the shortest delay in diagnosis of HIV infection.2 Therefore, evaluating HRQoL in this group of patients could aid in determining the impact of this disease on their health.

Finally, among the sociodemographic characteristics that may influence HRQoL, our results showed that patients who live with a partner had a higher score on the MCS. This positive relationship has also been found in prior studies,5,16 which suggests that living with a partner could be a protective factor for mental health quality in PLWHA.

In addition to sociodemographic characteristics, described above, various clinical factors may influence HRQoL in PLWHA. In our study, the PCS was seen to be affected by the time since HIV diagnosis. This was similar to that reported in other studies.6,25,26 This effect was stronger in those with more years since diagnosis, who had worse scores in all domains of the physical component, this being more evident in the domains of bodily pain and general health.

Moreover, this study did not find any differences in HRQoL aspects according to the patient's immunological status (CD4+ lymphocyte count) or virological status (viral load). This was similar to that reported by other groups.8,10 Concerning immunological status, a higher CD4+ lymphocyte count was associated with better physical health, and a lower CD4+ lymphocyte was associated with poorer mental health.28 By contrast, a systematic review concluded that there is a great deal of debate with regard to the impact of virological status on the HRQoL of PLWHA.7

Another clinical factor that appears to influence HRQoL is concomitant HCV infection. In our study, co-infection with this virus was associated with lower (worse) scores in all domains of the SF-36v2 and in both summary components. Notably, the values obtained for the domains of general health and bodily pain were evaluated as poor. In addition, patients perceived their pain to interfere with their day-to-day work. A study conducted in Spain yielded similar results for perceived general health and bodily pain.8

Our study has several limitations. First, patients were recruited from a single hospital and, although the sample was representative of PLWHA cared for at that healthcare centre, it may not be possible to generalise the results to the entire PLWHA population. Second, a generic quality-of-life questionnaire was used. While it has been used successfully in the HIV/AIDS population, by not using a specific instrument in our study it has possibly excluded certain aspects of HRQoL of particular interest in PLHWA. Third, the study data were collected five years ago. Finally, causality could not be determined by virtue of our study's cross-sectional design. Future longitudinal studies will be able to determine the causal directions of these variables. Our results suggest that socioeconomic status and co-infection with HCV influence quality of life with regard to physical health among adults living with HIV.

FundingThis study received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestNone.

We would like to thank the entire team of the Infectious Diseases Unit at Hospital General Universitario de Alicante and all the patients who took part in the study.

Please cite this article as: García-López YL, Bernal-Soriano MC, Torrús-Tendero D, Delgado de los Reyes JA, Castejón-Bolea R. Factores relacionados con la calidad de vida en personas que viven con el VIH en Alicante, España. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:127–133.