Several types of central and peripheral neurologic complications during primary and chronic HIV infection have been described in people living with HIV (PLWH).1 For instance, Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) that has rarely been reported as a neurologic complication during primary HIV infection (PHI).2

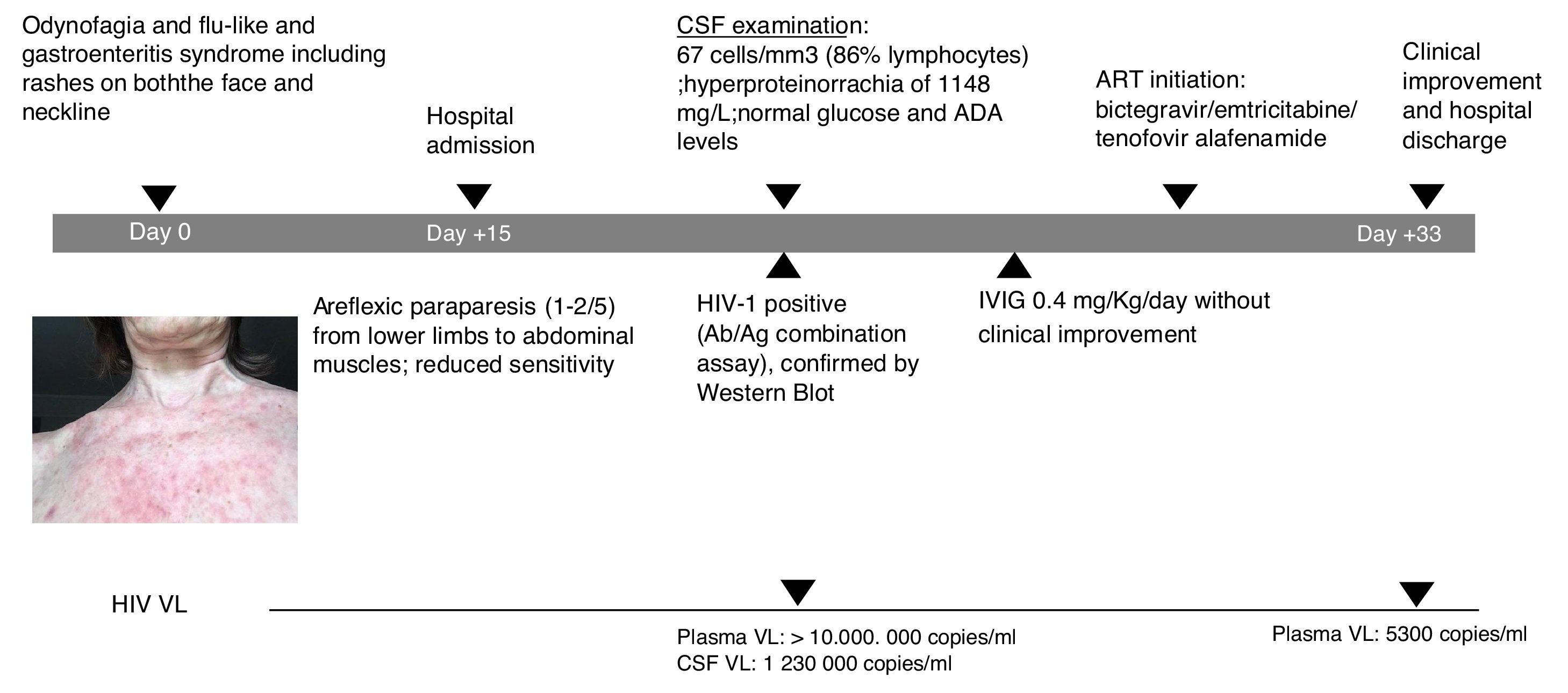

A 60-year-old female patient, originally from South America and on travel in Europe during the prior three weeks, presented with progressive lower limb weakness and pain, paresthesia and unstable gait. Two weeks prior to admission, she described odynophagia, diarrhoea and a flu-like syndrome with rashes present on both the face and neckline (Fig. 1). She was afebrile and haemodynamically stable upon clinical examination. At admission, she presented with moderate areflexic paraparesis (2/5) from the lower limbs to abdominal muscles, with reduced sensitivity. Biochemistry and red and white blood cell counts were unremarkable. Ganglioside antibody screen and tumor markers were normal. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) revealed pleocytosis with 67cells/mm3 (86% lymphocytes); hyperproteinorrachia of 1148mg/L (normal range≤500mg/L); and normal glucose and adenosine deaminase (ADA) levels. Microbiologic tests of CSF included polymerase chain reaction analyses and antibody testing for herpes virus, enterovirus, JC-polyomavirus and toxoplasma; all were negative. CSF and blood Cryptococcus neoformans antigen tested negative. Screening for other arthropod-borne viruses and opportunistic infections, and magnetic resonance imaging of brain and spinal cord were all unremarkable. Common enteric pathogens in faecal samples were negative by molecular detection and cultures. The patient was started on intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and did not improve.

Following the initial negative microbiologic tests, HIV serology was requested and tested positive. Western Blot (with only positive bands for gp41 and P24) confirmed PHI diagnosis. CD4 count was 334cells/mm3 and plasma HIV viral load (VL) was>10,000,000copies/mL (the upper limit of quantification in the institution's lab) and 1,230,000copies/mL in CSF. HIV subtype was BF recombinant; no resistance was detected.

Nerve conduction studies revealed signs of radicular demyelinating lesion in lower limbs. The patient started antiretroviral therapy (ART) with bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide at routine doses. She presented with good tolerance in response and muscle strength slowly yet constantly improved during the following two-to-three weeks.

Upon hospital discharge, she still presented with mild paraparesis and in need of a convalescent centre. However, she was able to be transferred to her country of origin. Plasma HIV VL at discharge was 5300copies/mL within only two weeks of ART initiation. The patient provided informed consent for publication of the case.

Association between GBS and HIV was first reported in 1985. GBS occurs concomitantly with HIV seroconversion or during initial phases of infection, but has also been reported during chronic HIV infection or as immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.3 The pathogenesis of GBS is not well known. However, investigators have suggested that HIV-1 performs a direct action on the nerves by neurotropic strains or autoimmune mechanisms, with antibodies targeted against myelin secondary to abnormal immunoregulation as determined by HIV infection.3,4

HIV-related neurologic disorders include cognitive impairment and peripheral nervous system involvement. Rarely may AIDP manifest, although it is one of the most common variants of GBS.5 GBS is more likely to appear during acute HIV infection than during advanced disease, albeit possible.6 Fever, mild respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms, and maculopapular rash are usually reported prior to the onset of GBS.5

Diagnosis is based on clinical features, including areflexia with bilateral weakness beginning in the legs and extending upwards to other limbs as well as possible severe respiratory and cardiac complications.5 Furthermore, diagnosis is confirmed with CSF analysis and electrophysiologic studies. CSF exam reveals increased protein levels and normal or mild increased cellularity. However, given the neurotropism of HIV, pleocytosis may be present. Indeed, our patient did not present with the typical albumino-cytologic dissociation7 although this may also be related to timing of the lumbar puncture.

The largest published series of HIV-associated GBS included 10 patients between 1986 and 1999. These PLWH presented with typical GBS findings.7 Similar to our case, three patients were found to have HIV at the time. This observation, therefore, highlights the importance of HIV testing in patients presenting with neurologic disease.

Plasmapheresis, IVIG and plasma exchange have been used to treat GBS in PLWH.8 As in our case, ART may improve neurologic symptoms. Symptomatic PHI and neurologic symptoms related to HIV are both indication for immediate ART, as suggested by the most recent international guidelines.9 High-genetic barrier Integrase strand transfer inhibitor-based therapy should be used, given the extremely high VL observed often in PHI and the need for immediate ART initiation without available virological test results, e.g., genotype.9,10 Clinicians and neurologists should be aware of this rare clinical presentation of PHI wherein typical CSF features (albumino-cytologic dissociation) are frequently absent.