High-risk human papillomaviruses (HR-HPV) infection has been associated with 90% of anal cancer cases. Women with abnormal cytology are a high-risk group to develop anal neoplasia. The aim of this study is to describe the prevalence and epidemiology of HR-HPV 16, 18, 45, and 58 anal infections in women with cervical abnormalities, as well as to assess E2 gene integrity.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was performed on 311 cervical and 311 anal samples from patients with abnormal cytology in two colposcopy clinics in Yucatan, Mexico. A specific PCR for oncogenes was performed in order to identify HVP 16, 18, 45 and 58. Real time PCR was used to amplify the whole HPV 16, 18, and 58 E2 gene to verify its integrity in anal samples.

ResultsHigh risk HPV 16, 18, 58, and/or 45 were found in 41.47% (129/311) of cervical samples, and in 30.8% (96/331) of anal samples, with 18% (57/311) of the patients being positive in both samples. The same genotypes in both anatomical sites were observed in 11.25% (35/311). The E2 gene was disrupted in 82% of all tested samples. The frequency of genome disruption viral integration in anal samples by genotype was: HPV 58 (97.2%); HPV 16 (72.4%), and HPV 18 (0%).

ConclusionWomen with cervical disease have HR-HPV anal infections, and most of them have the E2 gene disrupted, which represents a risk to develop anal cancer.

La infección por virus del papiloma humano de alto riesgo (AR-VPH) está asociada al 90% de los casos de cáncer anal; las mujeres con enfermedad cervical son un grupo de alto riesgo para desarrollar neoplasia anal. El objetivo de este estudio es describir la prevalencia y epidemiología de las infecciones anales por AR-VPH 16, 18, 45 y 58 en mujeres con citología anormal y evaluar la integridad del gen E2.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio transversal con 311 muestras cervicales y 311 muestras anales de pacientes con citología anormal de 2 clínicas de colposcopia en Yucatán, México. La identificación de los VPH 16, 18, 45 y 58 se realizó con una PCR específica para los oncogenes. Para verificar la integridad del gen E2 en muestras anales se utilizó PCR en tiempo real para la amplificación de todo el gen E2 de VPH 16, 18 y 58.

ResultadosLa presencia de AR-VPH 16, 18, 45 y/o 58 fue identificada en el 41,47% (129/311) de las muestras cervicales y en el 30,8% (96/331) de las muestras anales; el 18% de las pacientes (57/311) fueron positivas para ambas muestras, y el 11,25% (35/311) tuvieron el mismo genotipo en ambos sitios anatómicos. El gen E2 se encontró incompleto en el 82% de todas las muestras anales analizadas. La frecuencia de disrupción del genoma viral por genotipos fue: VPH 58 (97, 2%); VPH 16 (72, 4%) y VPH 18 (0%)

ConclusiónLas mujeres con enfermedad cervical están infectadas con AR-PVH en la región anal y la mayoría presentan disrupción del gen E2, lo que representa un riesgo para desarrollar cáncer anal.

The oncogenic role of human papillomavirus (HPV) has been established through decades of biological and epidemiological studies; in 2008 it was responsible for 610,000 new cases of neoplasias worldwide.1 E6 and E7 proteins are known for their oncogenic capacity, by interacting with cell cycle regulating proteins. Viral genome is a circular double stranded DNA molecule, and while it is maintained in episomal state, E1 and E2 proteins are responsible for down regulating the transcription of the oncogenes. HPV genome integration to the host is a relevant event for malignant transformation; the first step is the linearization of the viral genome mainly by the disruption of the E1/E2 gene, with loss of E2 open reading frame and up regulation of the E6 and E7 oncogenes leading to cell transformation.2 The evaluation of the E2 gene is useful to know the physical state of the viral genome.

The causal link between HPV and cancer has been proven for many squamous cell type carcinomas, as there is evidence to link it to cervical cancer (100%); anus (88% of cases); penis (50%), vaginal (70%), vulva (43%) and oro-pharynx (12–53%).1

Anal cancer represents less than 5% of cancers in the lower gastrointestinal tract, being more common in women than in men. In the last decade has been a worldwide increase in the incidence of anal cancer in both genders. Risk factors are receptive anal sex, lifetime number of sexual partners, history of genital warts and cigarette smoking.3

According to the National Register of Neoplasias in Mexico published in 2011, at least 2% of all digestive tract tumors corresponded to tumors of the anal region, showing a tendency to increase during the 2004–2006 period.4

Recent studies have shown that women with history of high-risk cervical lesions, or cervical (and/or vaginal) cancer have a higher risk of developing anal cancer in the next two decades after diagnosis, with an OR of 10.5 and 13.6.5,6 Gaudet7 reported an incidence of anal cancer of 3.7 per 100,000 person-year among 54,320 women with history of High grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions (HSIL) 10 years before.

However, epidemiological knowledge and clinical significance of anal infection with HR-HPV in women with cervical abnormalities is limited, most of the research had focused on HIV positives and men who have sex with men, and there are worldwide controversies about screening.8–10

The aim of this study was to describe the prevalence and epidemiology of HR-HPV 16, 18, 45 and 58 anal infections in women with cervical abnormalities, and assessing the E2 gene integrity in anal samples.

Material and methodsStudy design, participants and samplingA cross sectional study including women attending the Colposcopy Clinic of the General Hospital in Valladolid, Yucatan, Mexico, and the O’Horán General Hospital in Merida, Yucatan, Mexico, between April 2012 and April 2014 was done; both are public hospitals from the Health Minister, and provide medical service to women without social security insurance. All patients were referred to the colposcopy service after having an abnormal Pap smear during routine check-up. Protocol excluded pregnant women. After informed consent from each patient, physician collected cervical and anal samples during the colposcopy revision. Cervical cells were obtained according to Pap smear sampling procedure, while anal samples were taken with a dacron swab according a method describe by Nadal.11

Samples placed in 50% ethanol as transport medium. During the colposcopy revision, a cervical biopsy was taken for histopathological diagnostic purposes. Epidemiological data and clinical histories were assessed using a questionnaire that included inquiries of sociodemographic information, sexual behavior, hormonal contraceptives history and tobacco use.

Characteristics of the studied populationIn total, 311 women were included in this study. The mean age of the studied population was 38.6 years (16–78), and 48% were ≤35 years old. 76% live in rural communities, and at the time of the study 87% of participants were housewives, 12% were working in various fields and 1% were students. With respect to sexual behavior and reproductive history, the mean age at first intercourse was 17.9 years, 51.5% of 266 (45 missing data) participants had their first intercourse before the age of 18, and 8% had ≤3 sexual partners in their lifetimes. Of the total women studied, 4.2% have never been pregnant, 54% have had ≤3 pregnancies and 41.7% ≥4. Of the 298 women who have had at least one pregnancy, 69% have never had abortions; 19.4% had one; 11.4% have had repetitive abortions and 32% at least one of their pregnancies ended in cesarean section. 11.6% used hormonal contraception at the time of the study, and 36.6% were their first Pap smear. Finally, 4% of participants smoked and 19.2% reported passive tobacco exposure.

Ethical considerationsThis project was approved by the corresponding Scientific and Bioethics committee (CIE-044-2-11). All participants signed an informed consent form.

HPV DNA detection and typingDNA extraction procedure was performed using the Dneasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer's instructions and carried out by experienced personnel. β-globin amplification was performed for DNA quality control, using PC04 and GH20 primers (260bp amplicon).12 Nested PCR was used to detect the presence of HPV16, 18, 45 and 58, amplifying the E6 and E7 gene fragment using primers, temperatures and times previously reported.13 Positive controls were clinical samples previously identified by the same method and by Sanger sequencing. All PCR reactions were carried out in a DNA Engine thermal cycler (DYAD) and amplicons were visualized on 8% acrylamide gels using a 100bp molecular weight marker (Invitrogen).

E2 gene integrity evaluation in HPV types 16, 18 and 58E2 evaluation was performed by real time PCR using a StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). E2 gene from HPV16 was amplified in three fragments: amino terminus (551bp), hinge (152bp), and carboxyl terminus (103bp) according to previously described protocol in a final volume of 25μl.14 E2 gene from HPV18 was amplified in four fragments: amino terminus 1 (223bp), amino terminus 2 (175bp); hinge (192bp), and carboxyl terminus (177bp) according to previously described protocol in a final volume of 25μl.15 As positive control, plasmids of the full HPV16 and HPV18 genomes were used (kindly donated by Ethel-Michele de Villiers, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, Germany). E2 gene from HPV58 was amplified in four fragments: amino terminus 1 (182bp), amino terminus 2 (192bp); hinge (199bp), and carboxyl terminus (113bp) according to previously described protocol in a final volume of 25μl.16 As positive control, a plasmid of the full HPV58 genome was used (kindly donated by Toshiko Matsukura, Japan). HPV 45 E2 gene integrity was not evaluated.

Database analysisThe variables were analyzed in a database in SPSS software 20. The frequencies were calculated and bivariate analyses were performed. A chi square-test was used to determine association between anal HPV types 16, 18, 58, 45 and age, work, age at first sexual intercourse, number of sexual partners, smoking, passive tobacco exposure, first pap smear, cervical HPV 16, 18, 58, 45, and histopathology diagnosis of cervical lesions.

For the analysis, the following variables were categorized as follows: age of first intercourse: <18 years vs. ≥18 years; number of sexual partners: ≤2 vs. ≥3, histopathology diagnosis Low Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions (LSIL) vs. HSIL and CC. P-values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

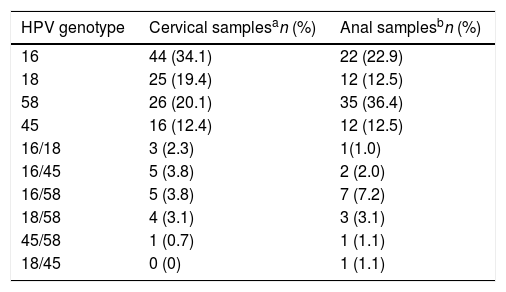

ResultsHPV infectionsSix hundred twenty-two samples were included (311 cervical and 311 anal samples); all samples amplified beta globin control, 225 were HPV positive to any of the genotypes included in the study (16, 18, 45 and 58). In 192 (85%) one HPV genotype was found, whilst in 33 (15%) two genotypes were identified. The frequency of the identified genotypes was HPV16 34% (89/258); HPV58 32% (82/258); HPV 18 19% (49/258); and HPV45 15% (38/225). The frequency of genotypes according to anatomical region (cervical and anal) is in Table 1.

High-risk HPV in cervical and anal samples of women with cervical lesions.

HPV prevalence found in cervical samples was 41.47% (129/311), and in anal samples 30.8% (96/311). Of notice, 18% (57/311) of all women included were positive in both samples; from these 61% (35/57) had the same genotype in cervical and anal samples.

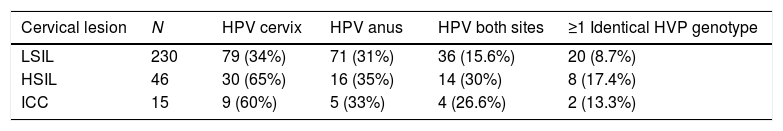

Double genotype infections were determined in 14% cervical and 15.6% anal samples. Table 2 shows the distribution of HPV in cervical and anal samples according cervical lesion grade.

Prevalence of HPV 16, 18, 45 and 58 in cervical and anal samples according diagnosis.

| Cervical lesion | N | HPV cervix | HPV anus | HPV both sites | ≥1 Identical HVP genotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSIL | 230 | 79 (34%) | 71 (31%) | 36 (15.6%) | 20 (8.7%) |

| HSIL | 46 | 30 (65%) | 16 (35%) | 14 (30%) | 8 (17.4%) |

| ICC | 15 | 9 (60%) | 5 (33%) | 4 (26.6%) | 2 (13.3%) |

LSIL, low squamous intraepitelial neoplasia; HSIL, high squamous intraepitelial neoplasia; ICC, invasive cervical cancer. N=291.

E2 gene integrity was investigated in 69 out of 96 positive anal samples: 29 HPV16 positive samples; 4 HPV18 positive samples, and 36 HPV58 positive samples. About HPV16 positive, 27.6% (8/29) amplified the whole E2 gene while 72.4% (21/29) did not amplify at least one fragment. The amino terminus was the most frequently disrupted (69%) followed by the carboxil terminus (24%) and the hinge (17%), in some samples more than one fragment did not amplified (thus the sum of percentages is more than 100%) HPV18 positives analyzed amplified for all E2 fragments, therefore disruption was not found. On the contrary, E2 HPV58 was incomplete in all samples (35/36, 97.2%) except one (2.8%); in 23 (65%) samples three E2 segments not amplified; in 9 (26%) two segments and only in 3 (9%) samples only one segment was absent. The hinge and the amino terminus 2 segments were found disrupted the most frequently (97 and 89% respectively), followed by amino terminus 1 (58%), while the carboxyl terminus was the less frequently found disrupted (6%).

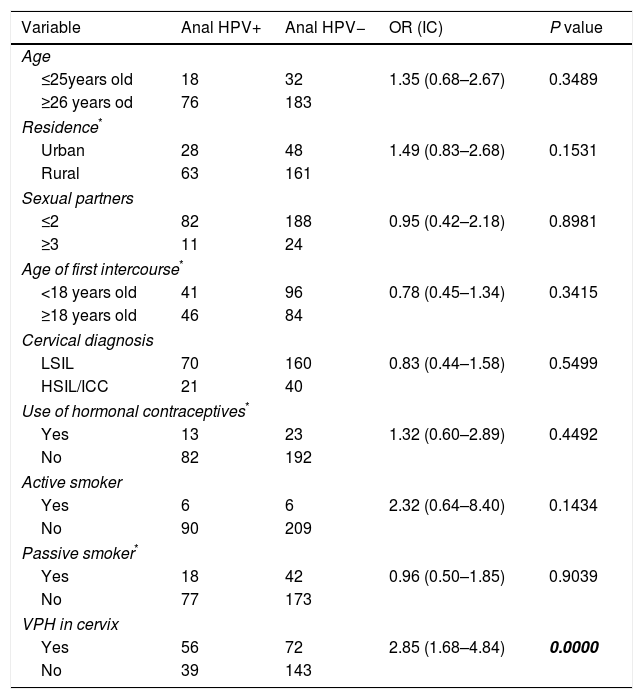

Variables associated to anal HPV infectionWe performed the analysis of the database from the variables recorded in the questionnaire, to determine which of them were associated to anal HPV infection. The results are summarized in Table 3. The presence of high risk genotypes 16, 18, 58 or 45 in cervix was the only variable associated to presence of HPV in anus; P=0.0000; OR=2.85; CI (1.68–4.84).

Bivariate analysis of the variables associated to anal HPV infection in the studied population.

| Variable | Anal HPV+ | Anal HPV− | OR (IC) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| ≤25years old | 18 | 32 | 1.35 (0.68–2.67) | 0.3489 |

| ≥26 years od | 76 | 183 | ||

| Residence* | ||||

| Urban | 28 | 48 | 1.49 (0.83–2.68) | 0.1531 |

| Rural | 63 | 161 | ||

| Sexual partners | ||||

| ≤2 | 82 | 188 | 0.95 (0.42–2.18) | 0.8981 |

| ≥3 | 11 | 24 | ||

| Age of first intercourse* | ||||

| <18 years old | 41 | 96 | 0.78 (0.45–1.34) | 0.3415 |

| ≥18 years old | 46 | 84 | ||

| Cervical diagnosis | ||||

| LSIL | 70 | 160 | 0.83 (0.44–1.58) | 0.5499 |

| HSIL/ICC | 21 | 40 | ||

| Use of hormonal contraceptives* | ||||

| Yes | 13 | 23 | 1.32 (0.60–2.89) | 0.4492 |

| No | 82 | 192 | ||

| Active smoker | ||||

| Yes | 6 | 6 | 2.32 (0.64–8.40) | 0.1434 |

| No | 90 | 209 | ||

| Passive smoker* | ||||

| Yes | 18 | 42 | 0.96 (0.50–1.85) | 0.9039 |

| No | 77 | 173 | ||

| VPH in cervix | ||||

| Yes | 56 | 72 | 2.85 (1.68–4.84) | 0.0000 |

| No | 39 | 143 | ||

Worldwide, HPV 16, 18 and 45 are the most frequently found in invasive cervical cancer and HSIL.17 HPV 58 is the seventh in frequency; important geographical variations are reported. In the southeastern Mexico this genotype together with HPV 16 are the most frequent among women with cervical diseases.18

Anal HPV infection has been most widely studied in men who have sex with men and in immunocompromised patients of both sexes,8–10 however women in general is an understudied group, and studies performed in women with HPV cervical diseases without HIV are scarce.19–23

Anal HPV prevalence found in our study was 30.8%, which is lower to previous report, although might not be fully comparable, because in our study only 4 genotypes were tested (16, 18, 45, 58), and therefore the general prevalence could be underestimated. The frequency of HPV in anal samples from women with cervical abnormalities reported previously: 45% (35 genotypes)19; 56.3% (19 genotypes)21; 91.4% (37 genotypes),20 32.5% (HR-HPV).23 Therefore, given these evidences, we can infer that at least 30% of women receiving care at dysplasia clinics are infected with a high-risk HPV in anal region.

From women infected in cervix and anus, 61% had at least one identical genotype in both sites; in the case of double infections, one patient had HPV16 and 45 in both sites. Previously, Valari20 reported 74.5% concordance in genotypes present in cervix and anus; Hessol22 found the same HPV genotypes in anal and cervical samples of HIV+ (13%) and HIV− (18%) women. Concordance of genotypes have been understudied in general, and the results have a wide range (8–74, 5%); these differences can be due to the methodologies used, and to the different risk factors for anal infection present in the studied populations. It is worth mentioning that in the present work, the cervical and anal samples were processed and analyzed by two different persons, and were never manipulated simultaneously, and therefore we rule out the possibility of cross contamination between the samples.

Recently, Schenal24 reported that the anal HPV prevalence increases accordingly to cervical lesion grade, from 15% in LSIL to 55% in microinvasive carcinoma. In our work this was not observed, as anal HPV prevalence was similar in all cervical lesion grades. In fact the hypothesis at the beginning of our research was that a higher cervical lesion would be related to a higher prevalence of anal HPV; assuming that women with HSIL would have been more exposed to being infected in anal region simply because of the long time it takes in natural history of infection to develop such cervical lesion. To test that, we compared the HPV anal infection prevalence in LSIL vs. HSIL/CC but the results were not significant (P=0.5499).

Risk factors associated to HPV anal infection in both sexes are: receptive anal sex, lifetime number of sexual partners, history of genital warts and cigarette smoking. In the case of women, the presence of HPV related cervical lesions is also an important risk factor.7,25 In our study, we did not found association with lifetime number of sexual partners, cigarette smoking, passive smoker, or cervical lesion grade; the only significantly associated risk factor was the presence of HPV in cervix (P=0.0000).

Knowledge of natural history of anal HPV among women is limited to women without cervical diseases and small cohorts. Moscicki26 studied 75 young heterosexual, 36.4% of anal HPV infection cleared within 36 months. Shvetsov27 reported a cohort of 431 sexually active women, the rate of clearance was 87% during the first year. In our study 58% (56/96) of HR-HPV anal infection had a viral genome disruption, without possibility of clear the infection. Longitudinal studies with diverse population are necessary to understand the impact of anal HPV.

The E2 gene disruption results in increased of mRNAs of oncogenes. Recently Veo28 analyzed the expression of E6 RNA HPV 16 and 18 in anal samples of women with cervical cancer and reported that 21.2% of women with genotype 16 and 19.2% with 18 were positive for RNA. These results are consistent with our results, and both studies provide evidences that an important percentage of women with cervical lesions are infected with HPV in the region anal and have begun viral changes associated to the development of neoplasia.

Recent evidence shows that all viral genes can break during the integration process, including late and long control region. In fact in the study of Hu Z et al., E1, L1 and L2 genes suffered ruptures more often than E2.29 Those results do not invalidate our work, but make clear that patients with complete E2 gene, not necessarily have an episomal genome. Under the light of the new knowledge it is necessary to analyze the entire genome to identify the viral physical state.

One of the limitations of our work is that receptive anal sex practices were not investigated, this was because of the characteristics of the studied population, 72% were women from rural area, where anal intercourse is not openly accepted, and even in the interview the mention of this sexual practice resulted uncomfortable and ashamed the women. However anal HPV has been reported in women without anal intercourse.30

In conclusion, women with cervical disease have HR-HPV anal infections, and the process of viral integration has already begun. It is imperative to perform studies in women without cervical pathology to gain knowledge of the determinants associated to the infection, and studies on other possible transmission routes different to anal intercourse. This knowledge is mandatory to gain enough evidence for implementing a routinely early detection program for women at risk of anal cancer.

FundingThe study was sponsored by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, SALUD-2011-162222.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.