This was a 63-year-old male, born in Spain, a smoker, with no other relevant medical history, studied by otolaryngology (ENT) for a roughly eight-month history of isolated dysphonia which had not improved with conventional treatment. Laryngoscopy showed organised oedema in both vocal cords, for which he had laryngeal microsurgery in May 2018.

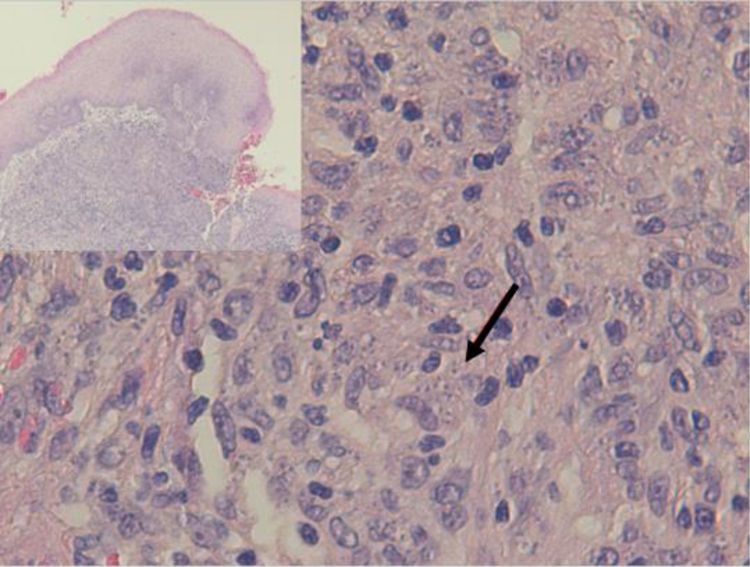

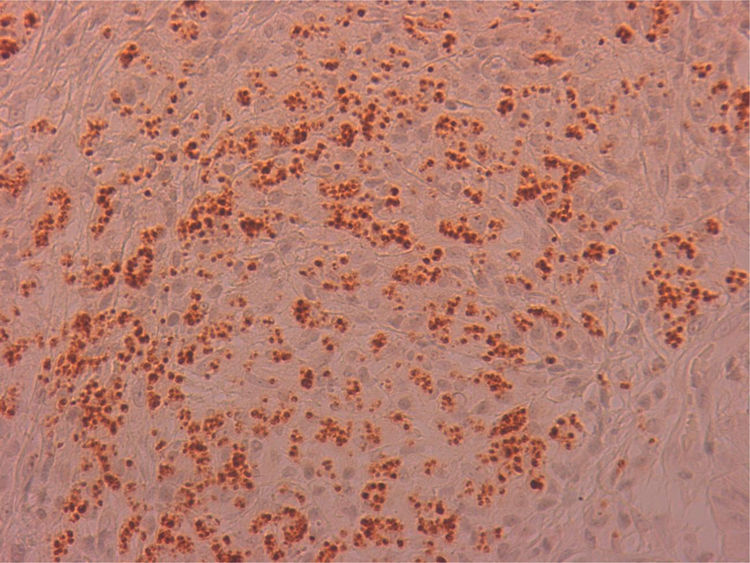

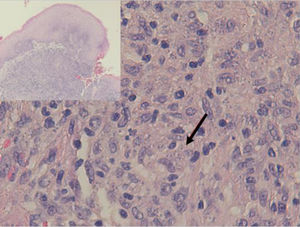

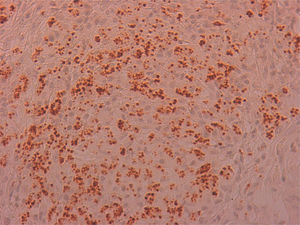

The excised material was sent to pathology for study, resulting in a diagnosis of non-necrotising granulomatous inflammation, with the presence of abundant microorganisms, which were stained with Giemsa (Fig. 1) and by immunohistochemical techniques with CD1a monoclonal antibodies (Fig. 2), morphologically compatible with amastigotes of Leishmania spp. in the right vocal cord and oedema, fibrosis and nonspecific inflammatory changes in the left vocal cord.

OutcomeFollowing the histological diagnosis, the patient was reassessed, finding he had made no recent trips abroad and lived in a rural environment in contact with domestic animals: dogs, hens and sheep. On physical examination, he had no skin lesions (nor had he had any) or organomegaly. Abdominal ultrasound showed no significant abnormalities. Serology was negative for hepatitis B and C viruses, the human immunodeficiency virus and Treponema pallidum. Serology for the detection of antibodies against Leishmania spp. was positive (titre 1/320). Part of the laryngeal biopsy was sent to the Centro Nacional de Microbiología (Spanish Microbiology Centre) in Majadahonda, where the DNA sequence of the ITS-1 region of the parasite was analysed and the species was identified as Leishmania infantum. All the data confirmed the diagnosis of primary laryngeal leishmaniasis. The patient received medical treatment with liposomal amphotericin B (3 mg/kg of body weight, one weekly dose for 7 weeks) with good outcome, and continued check-ups with ENT. Currently, 12 months after the initial diagnosis, the patient remains asymptomatic.

Closing remarksLeishmaniasis is a rare infectious disease, even in endemic countries like ours, and has very diverse forms of presentation. The clinical forms of leishmaniasis are cutaneous (CL), mucocutaneous (MCL), and visceral (VL). Leishmania infantum, the cause of leishmaniasis in our environment, is not usually included among the causes of MCL, which is usually due to New World (NW) species such as Leishmania braziliensis, amazonensis and mexicana (NWMCL). In fact, the WHO does not consider Spain an endemic area for MCL.1 The usual transmission is through the bite of an infected sandfly and the location of the lesion depends on the parasite and the immune response of the patient. The areas most commonly affected in MCL are the nose and mouth, with laryngitis being particularly rare.2–7

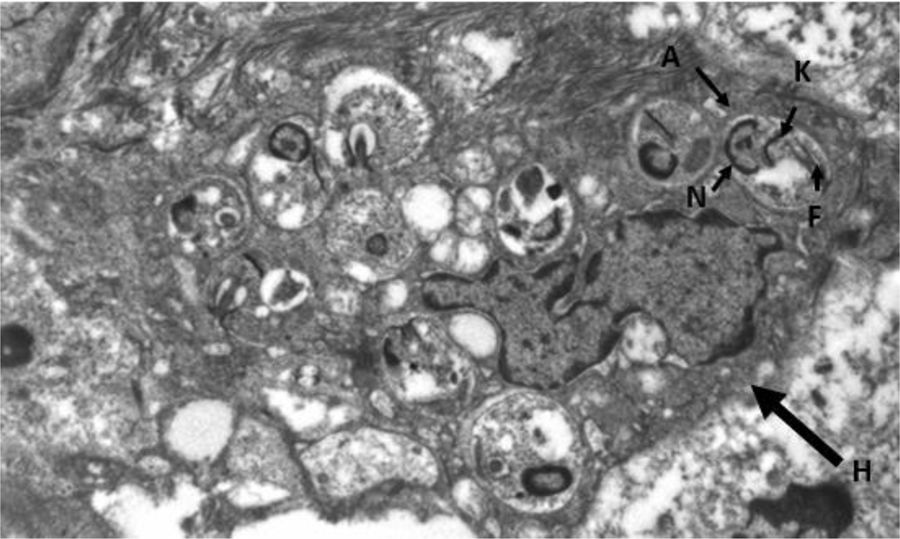

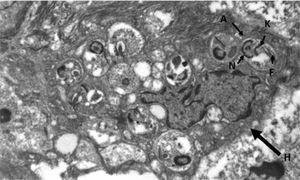

Dysphonia is the most common symptom in laryngeal leishmaniasis and indirect laryngoscopy usually shows localised lesions with an irregular and even ulcerated surface which raise a differential diagnosis with cancer.5 Clinical suspicion is rare when it is not associated with VL or CL, as in our case, and so it is essential to perform a biopsy to make a differential diagnosis with cancer or other chronic granulomatous diseases such as Paracoccidioides, Blastomyces, Actinomyces and histoplasma (in endemic areas).8 Histologically, it is characterised by non-necrotising granulomatous inflammation with the presence of abundant amastigotes within the histiocytes, which we identify as small ovoid bodies whose nucleus and kinetoplast stain with Giemsa and CD1a.9 Electron microscopy confirmed the presence of amastigotes (Fig. 3), but for the definitive diagnosis, confirmation and typing of the species is required by PCR and subsequent sequencing of the parasite's DNA10 which, as in our case, can be performed from samples previously paraffin-embedded.

It is interesting to highlight certain differences described in the literature between NWMCL and that caused by L. infantum (LiMCL), such as the more frequent nasal involvement in the former (90% versus 15%), or the better prognosis of the latter, despite the fact that nearly half of the patients have some type of immunosuppression or that, paradoxically, the more destructive lesions of NWMCL tend to have a low parasite presence compared to the high parasite load of the lesions in LiMCL.11

There are very few reports of leishmaniasis located in the vocal cords,1–7 and when it does occur, it is more common in immunocompromised patients.5 In our case, the patient had no relevant medical history, except being a smoker, which has been identified as a risk factor2 due to the chronic damage to the mucosa.

This type of lesion is currently treated with liposomal amphotericin B due to its potential efficacy and good tolerance,10 although scientific evidence on its use in processes such as the one discussed here is very limited and based solely on case reports.11 Periodic follow-up should be carried out to detect reactivation, which is more common in mucosal Leishmaniasis, like our case.

Please cite this article as: Betancor Santos MÁ, Vasallo Vidal FJ, Chicharro Gonzalo C, San Miguel Fraile MP. Disfonía prolongada de causa desconocida en un varón de 63 años. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:302–303.