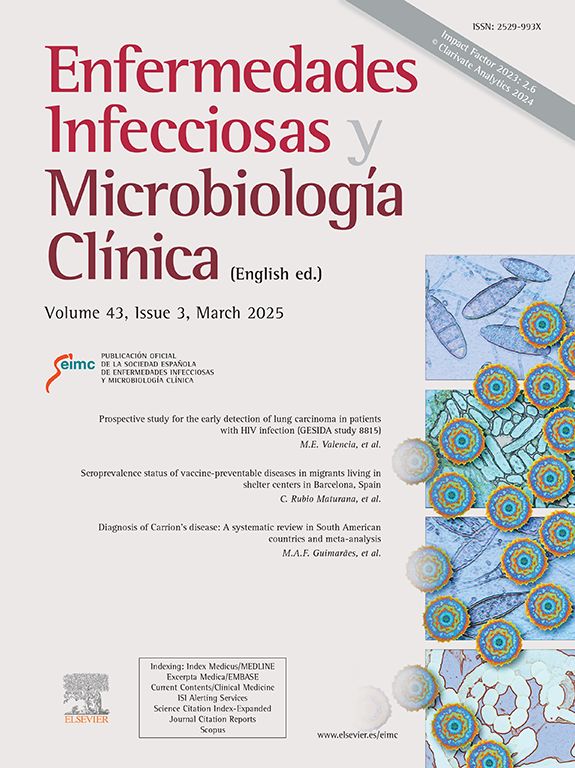

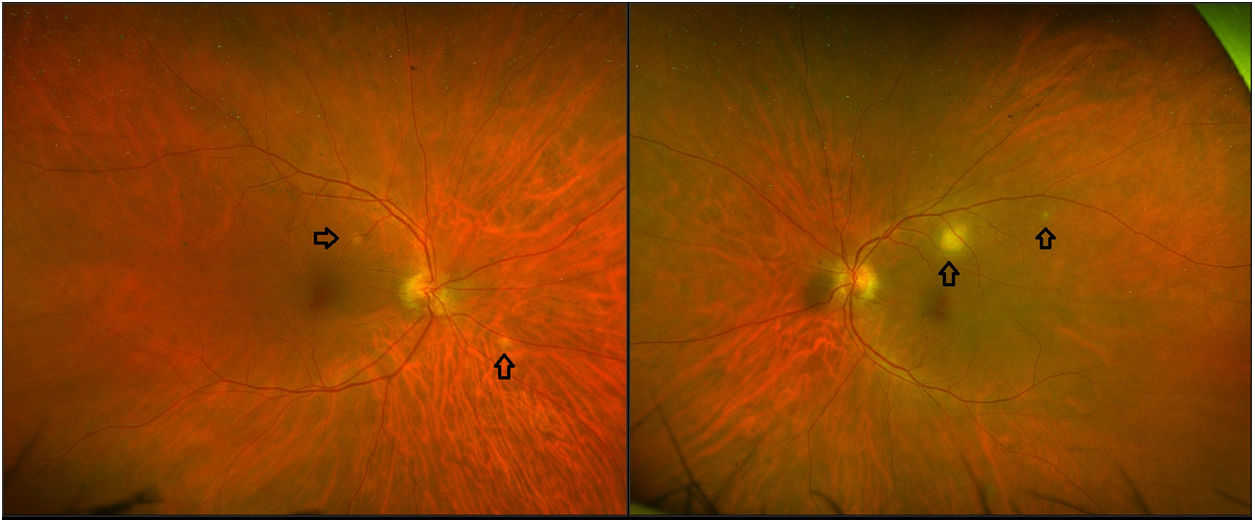

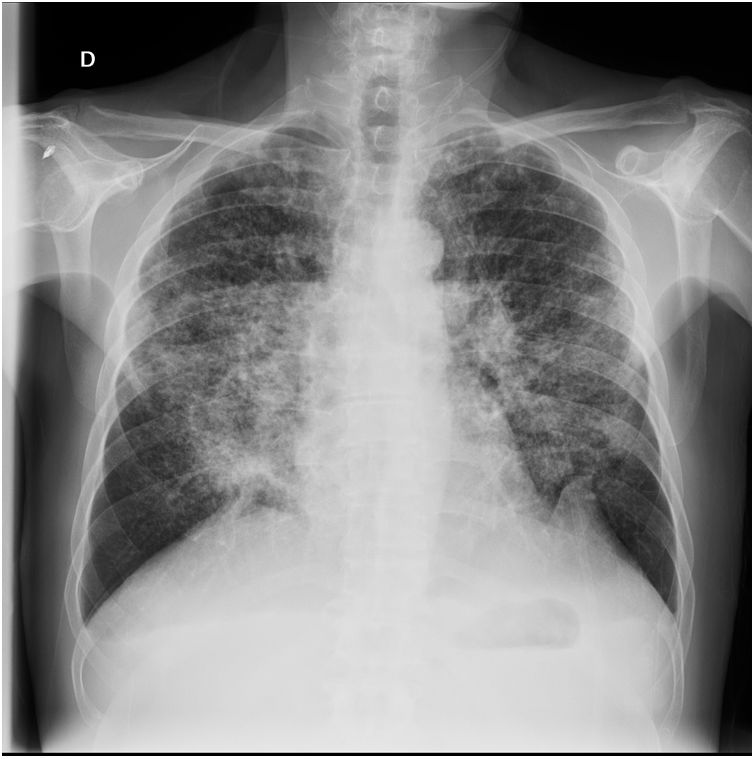

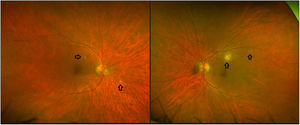

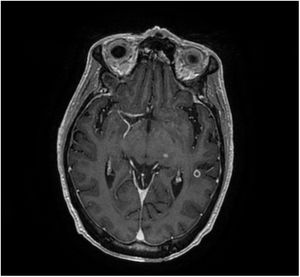

An immunocompetent 64-year-old man, smoker of 22 pack-year and drinker of 20g/day, presented with fever with spikes up to 39° and weight loss for some days. He also complained of easy fatigability, headache, blurred vision in both eyes, diplopia, vomit and lower urinary tract symptoms. Examination of the fundus showed papilledema and multiple ill-defined elevated subretinal yellow lesions located in the posterior pole and in the mid-periphery in both eyes, highlighting a larger lesion with the same features in left eye (Fig. 1). Optical coherence tomography suggested lesions at the level of choroidal stroma. Laboratory results revealed normocytic normochromic anemia and elevated values of reactive C protein. On the chest radiograph and CT image appeared numerous micronodules uniform in size and widespread in distribution (Fig. 2). Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging was carried out revealing leptomeningeal enhancement and parenchymal disease consisting on the presence of multiple well-defined nodular low signal lesions located in the supratentorial and infratentorial compartments which, following the injection of gadolinium, enhanced peripherally, as the one showed on this T1 axial image with contrast (Fig. 3).

Magnetic resonance imaging showed leptomeningeal enhancement and parenchymal disease consisting on the presence of multiple well-defined nodular low signal lesions which, following the injection of gadolinium, enhanced peripherally, as the one showed on this T1 axial image with contrast.

Further study revealed interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) positive. HIV and HCV serologies were negative and HBV serology manifested past infection. VDRL test was negative. Sputum and urine cultures were positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MT). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for MT DNA detection in cerebrospinal fluid was positive. Patient was diagnosed of miliary tuberculosis with genitourinary, lung, ocular and central nervous system (CNS) involvement. Color fundus photograph shows bilateral choroid tubercles in both eyes (Fig. 1), which are pathognomonic of miliary tuberculosis,1 and papilledema, which was caused by intracranial hypertension. Chest radiograph reveals typical miliary pattern (Fig. 2). Cerebral magnetic resonance shows leptomeningitis and cerebral tuberculomas (Fig. 3). Culture revealed a fully susceptible M. tuberculosis strain and the patient started treatment with daily isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol as well as corticosteroid treatment. The patient presented a favorable evolution of the disease with a good tolerance to the treatment and a progressive disappearance of the symptoms that was kept when patient was discharged from the hospital and continued treatment at home.

Final commentaryTuberculosis remains one of the most common infectious diseases, even in the immunocompetent population. Approximately one-third of the world's population is currently infected with tuberculous bacillus, of which approximately 5–10% become sick or infectious at some time during their life.2 Miliary presentation is a rare and possibly lethal form, accounting for 1–2% of all tuberculosis cases, resulting from massive lymphohematogenous dissemination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli.3

Choroid tubercles, located in the posterior pole (Fig. 1) constitute an early valuable clue to the diagnosis, as their presence is pathognomonic of miliary tuberculosis. Fundus examination must be done in all patients with suspected miliary tuberculosis.1 This fact gets a higher importance in this disease as its prognosis depends largely on neurological status at presentation and time-to-treatment initiation. Empiric treatment ought to be started as soon as tuberculosis is suspected.3

It is quite important to notice the presence of neurological involvement, especially meningitis, to ensure an adequate duration of treatment and asses the employment of corticosteroids.1 Antimicrobial therapy requires longer duration than for pulmonary forms and adjunctive corticosteroid treatment is considered to be beneficial in cases with meningitis.4 Cerebrospinal fluid characteristics in CNS tuberculosis are variable and may even be normal.3 Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (Fig. 3) is usually the test of choice in the diagnosis of CNS tuberculosis as it is considered superior to computed tomography.3 Furthermore, follow-up imaging allows to measure the response to anti-tuberculous pharmacotherapy, with the degree of contrast enhancement and surrounding edema related to the activity within the tuberculoma.5,6