To describe the levels of anxiety in the face of death in professionals from hospital emergency services in Aragon. To analyse its association with sociodemographic, perception and work-related variables.

MethodologyObservational, descriptive and cross-sectional study. The population and context of the study were health professionals in the hospital emergency services of Aragon. A non-probabilistic sampling selection was applied (n = 230 participants). The “Collet-Lester-Fear-of-Death-Scale” instrument was introduced to measure anxiety about death. The data was collected with a self-applied telematic questionnaire. Descriptive and inferential statistics were performed to analyse the association between the study variables.

ResultsMean values obtained for anxiety in the face of death were 94.58 ± 21.66 with a CI of 95%: (91.76–97.39) (range of scale: 28–140 points). A significant association was identified with the professional category variables (physicians, medical residents, nurses, and auxiliary nurses) (p: 0,006), gender (p: 0.001), level of training in emotional self-management (p: 0.03), self-perceived level of mental health (p: 0.07) and perception of lack of support from palliative care/mental health professionals (p: 0.006). This association was not obtained with the variables age (Sig: 0.558), total professional experience (p: 0.762) and in emergencies (p: 0.191).

ConclusionThe levels of anxiety in the face of death in the emergency hospital services are lower than those presented in other hospital units. Variables such as professional category, degree of training in emotional self-management and self-perceived level of mental health are related to levels of anxiety in the face of death and their study requires further work.

Describir los niveles de ansiedad ante la muerte en profesionales de los servicios de urgencias hospitalarios de Aragón. Analizar su asociación con las variables sociodemográficas, de percepción y laborales.

MetodologíaEstudio observacional, descriptivo y transversal. La población y contexto del estudio fueron los profesionales sanitarios de los servicios de urgencias hospitalarios de Aragón. Se aplicó un muestreo no probabilístico (n = 230 participantes). Se utilizó el instrumento “Collet-Lester-Fear-of-Death-Scale” para medir la ansiedad ante la muerte. Los datos se recogieron con un cuestionario telemático autoaplicado. Se realizó un estadístico descriptivo e inferencial para analizar la asociación entre las variables de estudio.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron unos valores medios de 94,58 ± 21,66 de ansiedad ante la muerte, (rango de la escala: 28–140 puntos). Se obtuvo una asociación significativa con las variables categoría profesional (entre médicos, residentes de medicina, enfermeras y técnicos en cuidados auxiliares de enfermería) (p: 0,006), sexo (p: 0,001), nivel de formación de autogestión emocional (p: 0,03), autopercepción del nivel de salud mental (p: 0,07) y percepción de falta de apoyo por profesionales de cuidados paliativo/salud mental (p: 0,006). No se obtuvo dicha asociación con las variables edad (p: 0,558), experiencia profesional total (p: 0,762) y en urgencias (p: 0,191).

ConclusiónLos niveles de ansiedad ante la muerte en los servicios de urgencias hospitalarios son más bajos que los presentados en otras unidades hospitalarias. Variables como la categoría profesional, el grado de formación en autogestión emocional y la autopercepción del nivel de salud mental se encuentran relacionadas con los niveles de ansiedad ante la muerte y su estudio requiere una mayor profundización.

Healthcare professionals may experience anxiety about death during the care of patients near the end of life. The study of the phenomenon has been carried out in various care settings, and an association has been observed between this anxiety and the socio-demographic variables analysed, such as age, gender and level of education.

What we contributeThe results obtained provide an approach to how the professionals involved (doctors, residents, nurses and auxiliaries) cope with the death of patients in emergency wards. The information analysed provides a greater understanding of the phenomenon in these services and may be of help in planning the activities necessary to improve terminal care there.

Currently, the concept of death and coping with death is considered a taboo subject in Western societies.1 However, in recent years there has been a change in trends in research and in the exercise of the healthcare policies involved. An example of this is the number of studies published on the impact of this phenomenon, such as those referring to the approval of Organic Law 3/2021, of 24th March, regulating euthanasia in Spain, or the study of the psychological impact that coping with death has had on frontline professionals.2,3

Coping with death can be defined as a professional competence that encompasses the strategies that individuals must possess, in practical terms, to solve problems and maintain their physical and mental integrity. These competencies comprise a construct that represents a wide range of human abilities and capabilities which enable individuals to cope with death, beliefs and attitudes towards these capabilities.4 In the case of hospital emergency services (HESs), coping with death is influenced by a series of characteristics that make end-of-life care difficult. This is often described by professionals as a stressful environment with a high demand for care that limits the time to provide care effectively.5 On the other hand, in a structured and life-saving environment, death is often seen as a failure of care, with feelings of avoidance and rejection of the process emerging.6,7 When death occurs in these services in the case of patients with an advanced and incurable disease or condition, feelings towards death are also negative, with avoidance and indifference towards the process, as it is not considered by professionals as an HES function.8,9 These characteristics, together with the rejection of understanding death as a stage of life in today's society, make it difficult to care for and cope with the process in the HESs, which may imply a greater risk of anxiety among the professionals involved.10

Fear of death is described by the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA) as “apprehension, worry or fear related to one's own death or dying”.11 In research, this term is also known as fear, panic or phobia of death and, although there is a great deal of debate about the use of these terms as synonyms, the complexity involved in defining this process has resulted in them usually being accepted and considered as equivalent.12,13 In health professionals, anxiety (or fear) of death has been linked to some key aspects of end-of-life care, such as the communication of bad news or increased exposure to pain, suffering and dying.13,14 Research has focussed on the study of fear of death in units where end-of-life care is routinely provided, most frequently in palliative care and haemato-oncology services.10,15 Another of the most widely represented populations has been that of professionals in training, with special interest being shown in medical and nursing students.16–18 However, studies on this subject are scarce in HESs, reinforcing the need to study how healthcare professionals perceive anxiety and fear of death in this setting, and analysing the variables and characteristics that could influence them.

The main objective of the study was to describe the prevalence of levels of anxiety and fear of death in healthcare professionals in the HESs in Aragon (Spain). Similarly, the secondary objective was to analyse the possible association between fear of death and sociodemographic, perception-related and occupational variables.

MethodologyResearch design. Observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study.

Study population and sample. The population consisted of healthcare professionals (doctors, family and community medicine residents - MIR -, nurses and auxiliary nurses – TCAE in its Spanish acronym) belonging to HESs in public hospitals in the Autonomous Community of Aragon (Spain). Non-probabilistic sampling was used. The total initial population was 703 professionals. The response rate was 34.28%, obtaining a final sample of n = 230 participants (11 cases were excluded due to lack of data for some of the variables).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria. The sample included participants with experience equal to or greater than one year in the HES. Professionals belonging to centres restricted to the maternity and paediatric populations were excluded.

Application and data collection. Data collection was carried out by means of a self-administered telematic survey between 1 st July and 30th September, 2021. Access to the link was provided to the professionals by the consultants and nursing supervisors. Their authorisation was requested for the study to be carried out in their respective services.

Measuring instruments. The Collett-Lester Fear of Death Scale (CLFDS) was used to analyse the variable “fear of death”. This instrument is composed of four independent subscales that together encompass the meaning of the phenomenon: (1) Fear of own death (FOD); (2) Fear of one's own dying process (FDP); (3) Fear of the death of others (FDO); (4) Fear of the dying process of others (FDPO). Each is composed of 7 items that are measured on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 5 points: (5 = Very high, 4 = high, 3 moderate, 2 = low, 1 = none), with the minimum and maximum values for each being 7 and 35 points respectively. The total range of the CLFDS scale is 28–140 points (higher values indicate a higher degree of fear of or fear of death).

For the study, the version adapted to Spanish by Tomás-Sabado et al.19 was used. This was validated in a sample of Spanish-speaking nurses and nursing students. The values obtained for Cronbach's alpha coefficient during this study were 0.83, 0.89, 0.79 and 0.86 for the subscales FOD, FDP, FDO and FDPO respectively, obtaining results consistent with those presented by other authors.13

Study variables. The sociodemographic and perception-related variables collected were: gender; age; marital status; cohabitation; number of children; perception of physical and mental health; perception of limiting chronic illness; and perception of religious/spiritual beliefs. The variables related to work and professional activity were: professional category; years of total and HES experience; level of HES centre where they work; level of training in palliative care and emotional self-management and professional communication skills; perception of avoidance, relocation, depersonalisation in end-of-life care in the service; and perception of external support from palliative care/mental health professionals.

Extraction and analysis. In the descriptive statistical analysis, the total and percentages were estimated for qualitative variables, and the mean, standard deviation and confidence intervals with a precision of 95% (95% CI) for quantitative variables. In the inferential analysis, the statistical relationship was tested between the CLFDS variable, and each of its 4 subscales, with the rest of the study variables. The t-student test was used for dichotomous qualitative variables, the one-factor ANOVA statistic for polytomous variables and Pearson's correlation for quantitative variables. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used for all statistical tests. Data analysis was performed using the statistical package SPSS-Version 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Ethical considerations. The project was previously approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aragon (CEICA). Data collection was undertaken in accordance with the provisions of the Helsinki Declaration and Organic Law 3/2018, of 5th December, on the Protection of Personal Data and the guarantee of digital rights.

ResultsThe “fear of death” study variable (CLFDS) obtained a mean of 94.58 ± 21.66), with a CI of 95%: 91.76−97.39. For each of the subscales, the following mean values and CI were obtained: 1) FOD, mean 20.52 ± 7.20 and CI 95%: 19.58–21.45; 2) FDP, mean 25.9 ± 6.35 and CI 95%: 25.07–26.72; 3) FDO, mean 25.09 ± 6.02 and CI95%: 24.31–25.87; 4) FDPO, mean 23.07 ± 6.33) and CI 95%: 22.25−23.9.

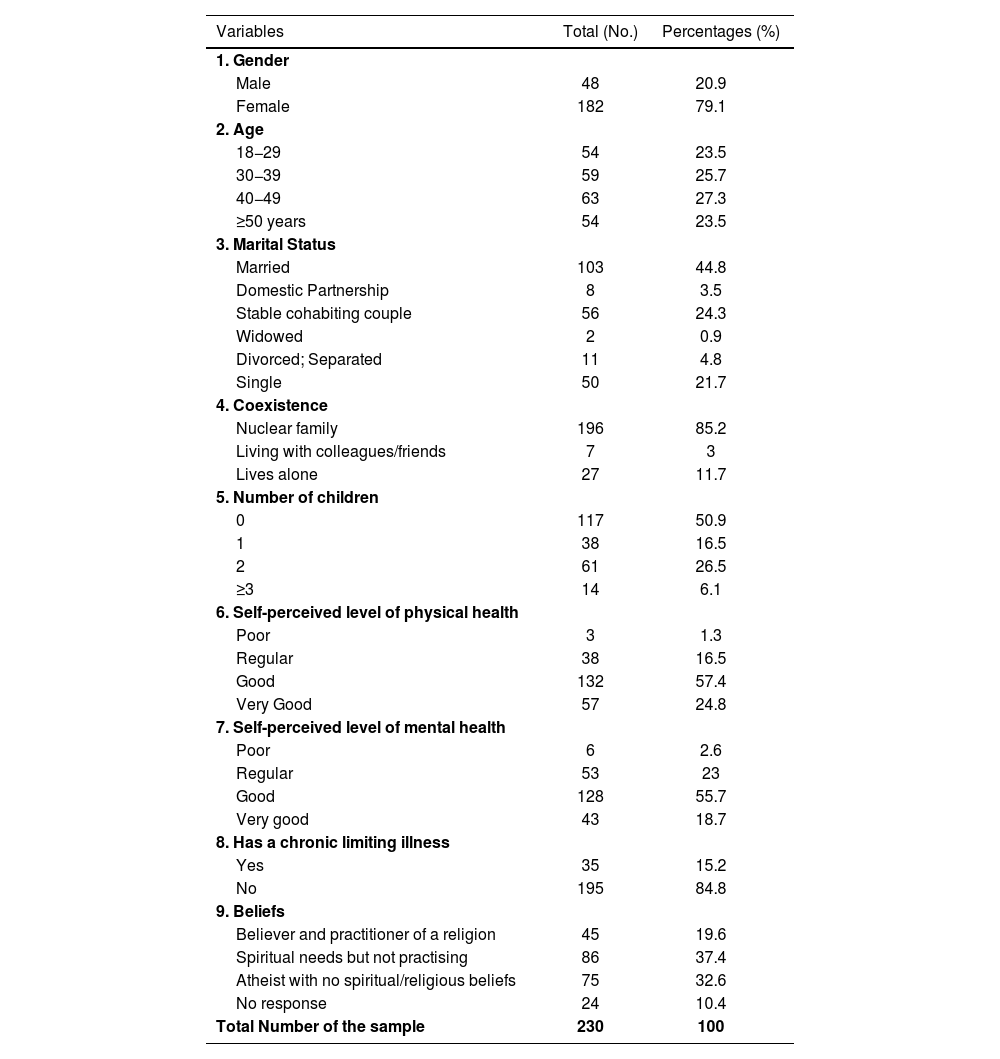

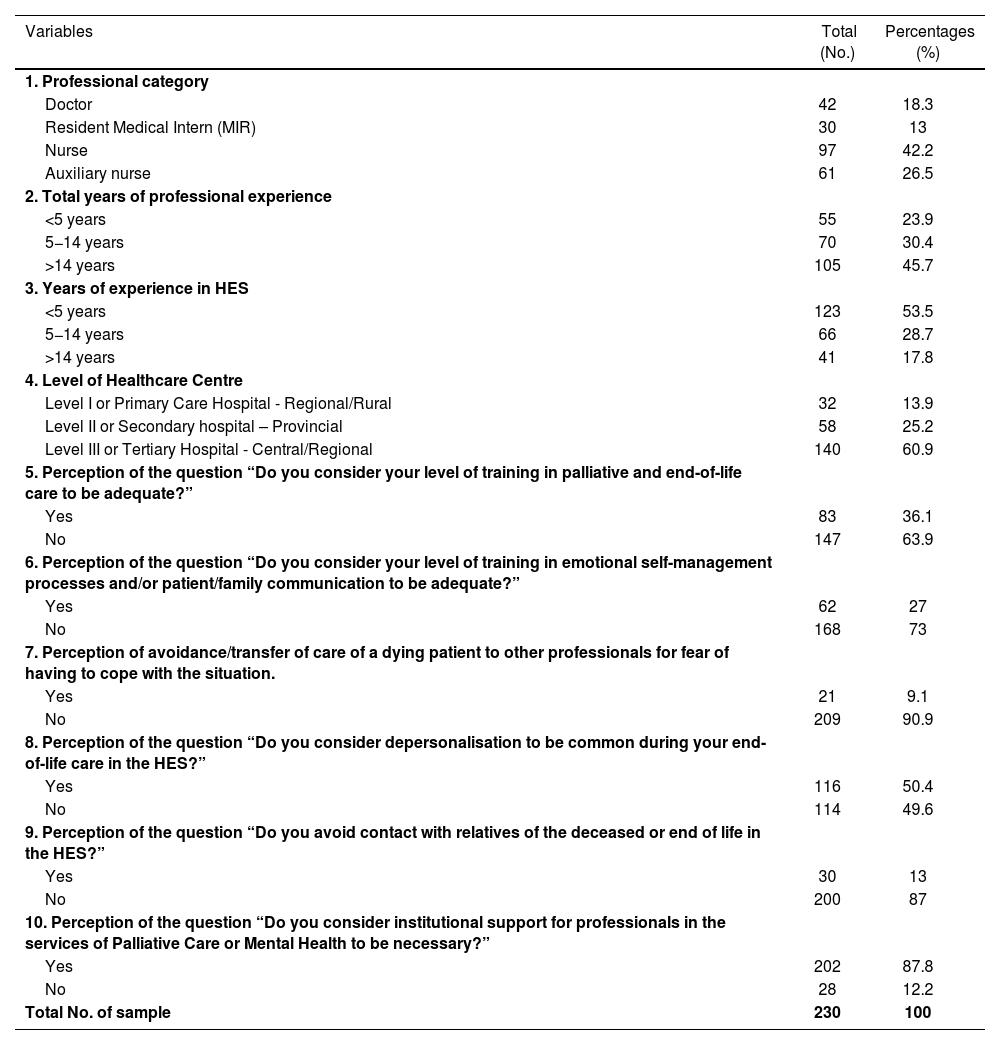

The mean age of the sample was 40.08 ± 11.07 years with a 95% CI of 38.64–41.52 years. The mean professional experience of the participants was 13.72 ± 9.95, with a 95% CI of 12.43−15.01. The total HES experience was 7.55 ± 8.08 years on average, 95% CI 6.5−8.6. The results of the descriptive statistics of the study variables are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Description of socio-demographic and self-perception variables.

| Variables | Total (No.) | Percentages (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | ||

| Male | 48 | 20.9 |

| Female | 182 | 79.1 |

| 2. Age | ||

| 18−29 | 54 | 23.5 |

| 30−39 | 59 | 25.7 |

| 40−49 | 63 | 27.3 |

| ≥50 years | 54 | 23.5 |

| 3. Marital Status | ||

| Married | 103 | 44.8 |

| Domestic Partnership | 8 | 3.5 |

| Stable cohabiting couple | 56 | 24.3 |

| Widowed | 2 | 0.9 |

| Divorced; Separated | 11 | 4.8 |

| Single | 50 | 21.7 |

| 4. Coexistence | ||

| Nuclear family | 196 | 85.2 |

| Living with colleagues/friends | 7 | 3 |

| Lives alone | 27 | 11.7 |

| 5. Number of children | ||

| 0 | 117 | 50.9 |

| 1 | 38 | 16.5 |

| 2 | 61 | 26.5 |

| ≥3 | 14 | 6.1 |

| 6. Self-perceived level of physical health | ||

| Poor | 3 | 1.3 |

| Regular | 38 | 16.5 |

| Good | 132 | 57.4 |

| Very Good | 57 | 24.8 |

| 7. Self-perceived level of mental health | ||

| Poor | 6 | 2.6 |

| Regular | 53 | 23 |

| Good | 128 | 55.7 |

| Very good | 43 | 18.7 |

| 8. Has a chronic limiting illness | ||

| Yes | 35 | 15.2 |

| No | 195 | 84.8 |

| 9. Beliefs | ||

| Believer and practitioner of a religion | 45 | 19.6 |

| Spiritual needs but not practising | 86 | 37.4 |

| Atheist with no spiritual/religious beliefs | 75 | 32.6 |

| No response | 24 | 10.4 |

| Total Number of the sample | 230 | 100 |

Variables related to work activity in HESs.

| Variables | Total (No.) | Percentages (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Professional category | ||

| Doctor | 42 | 18.3 |

| Resident Medical Intern (MIR) | 30 | 13 |

| Nurse | 97 | 42.2 |

| Auxiliary nurse | 61 | 26.5 |

| 2. Total years of professional experience | ||

| <5 years | 55 | 23.9 |

| 5−14 years | 70 | 30.4 |

| >14 years | 105 | 45.7 |

| 3. Years of experience in HES | ||

| <5 years | 123 | 53.5 |

| 5−14 years | 66 | 28.7 |

| >14 years | 41 | 17.8 |

| 4. Level of Healthcare Centre | ||

| Level I or Primary Care Hospital - Regional/Rural | 32 | 13.9 |

| Level II or Secondary hospital – Provincial | 58 | 25.2 |

| Level III or Tertiary Hospital - Central/Regional | 140 | 60.9 |

| 5. Perception of the question “Do you consider your level of training in palliative and end-of-life care to be adequate?” | ||

| Yes | 83 | 36.1 |

| No | 147 | 63.9 |

| 6. Perception of the question “Do you consider your level of training in emotional self-management processes and/or patient/family communication to be adequate?” | ||

| Yes | 62 | 27 |

| No | 168 | 73 |

| 7. Perception of avoidance/transfer of care of a dying patient to other professionals for fear of having to cope with the situation. | ||

| Yes | 21 | 9.1 |

| No | 209 | 90.9 |

| 8. Perception of the question “Do you consider depersonalisation to be common during your end-of-life care in the HES?” | ||

| Yes | 116 | 50.4 |

| No | 114 | 49.6 |

| 9. Perception of the question “Do you avoid contact with relatives of the deceased or end of life in the HES?” | ||

| Yes | 30 | 13 |

| No | 200 | 87 |

| 10. Perception of the question “Do you consider institutional support for professionals in the services of Palliative Care or Mental Health to be necessary?” | ||

| Yes | 202 | 87.8 |

| No | 28 | 12.2 |

| Total No. of sample | 230 | 100 |

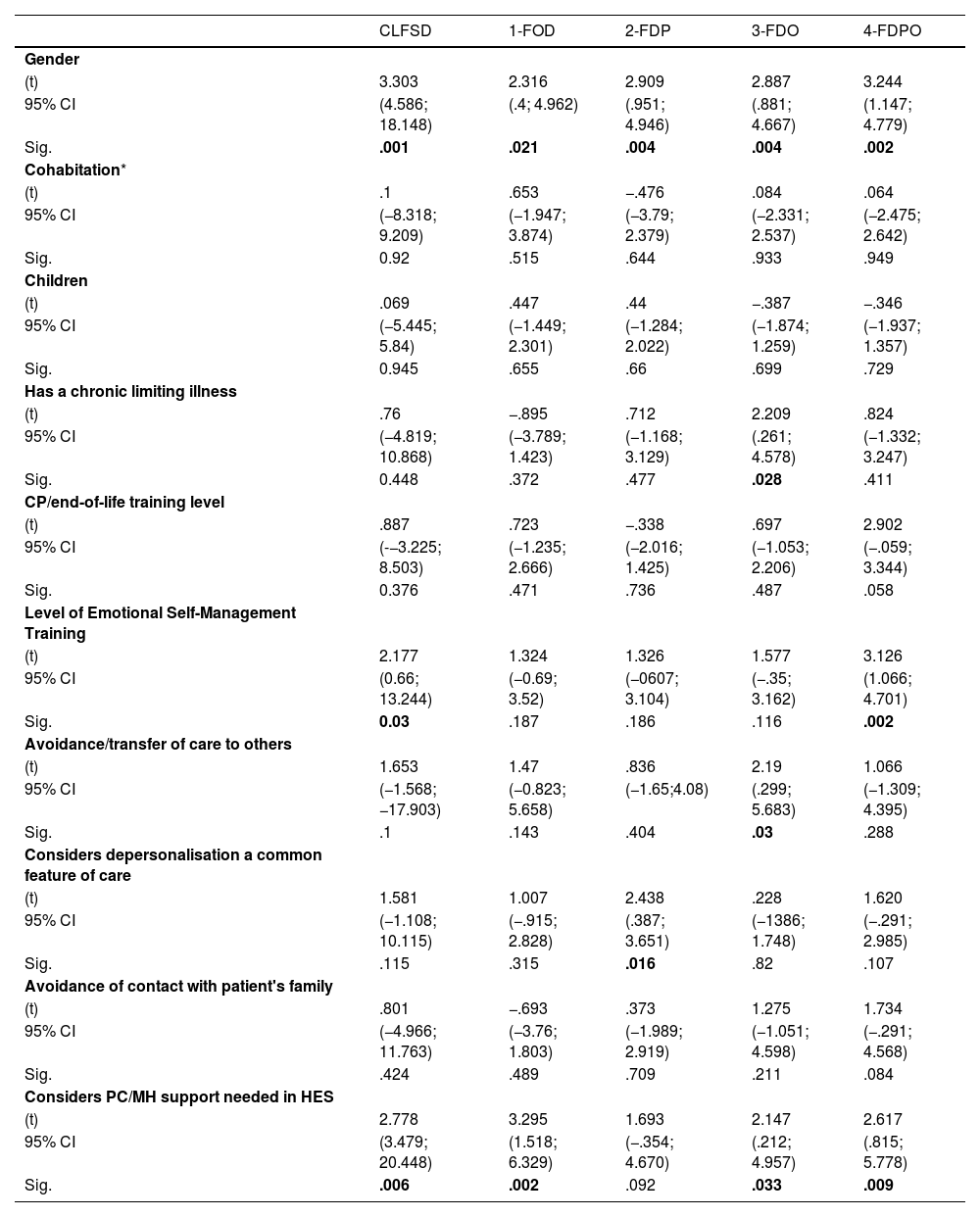

The inferential statistic obtained a significant association between the values of fear of death (and all the CLFDS subscales) with the professional category variables (p: 0.006) and gender (p: 0.001). The variables that obtained a statistically significant association in the CLFDS, but only in some of its subscales, were: level of training in emotional self-management (p: 0.03), self-perception of the level of mental health (p: 0.07) and perception of lack of support by palliative care or mental health professionals (p: 0.006). No association was found with age (p: 0.558), total professional experience (p: 0.762) and that described in the HES (p: 0.191). A summary of the bivariate analysis run is shown in Tables 3–5.

Results of the inferential analysis of Student’s t statistic. Relationship between CLFSD, its subscales and the dichotomous variables in the sample.

| CLFSD | 1-FOD | 2-FDP | 3-FDO | 4-FDPO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| (t) | 3.303 | 2.316 | 2.909 | 2.887 | 3.244 |

| 95% CI | (4.586; 18.148) | (.4; 4.962) | (.951; 4.946) | (.881; 4.667) | (1.147; 4.779) |

| Sig. | .001 | .021 | .004 | .004 | .002 |

| Cohabitation* | |||||

| (t) | .1 | .653 | −.476 | .084 | .064 |

| 95% CI | (−8.318; 9.209) | (−1.947; 3.874) | (−3.79; 2.379) | (−2.331; 2.537) | (−2.475; 2.642) |

| Sig. | 0.92 | .515 | .644 | .933 | .949 |

| Children | |||||

| (t) | .069 | .447 | .44 | −.387 | −.346 |

| 95% CI | (−5.445; 5.84) | (−1.449; 2.301) | (−1.284; 2.022) | (−1.874; 1.259) | (−1.937; 1.357) |

| Sig. | 0.945 | .655 | .66 | .699 | .729 |

| Has a chronic limiting illness | |||||

| (t) | .76 | −.895 | .712 | 2.209 | .824 |

| 95% CI | (−4.819; 10.868) | (−3.789; 1.423) | (−1.168; 3.129) | (.261; 4.578) | (−1.332; 3.247) |

| Sig. | 0.448 | .372 | .477 | .028 | .411 |

| CP/end-of-life training level | |||||

| (t) | .887 | .723 | −.338 | .697 | 2.902 |

| 95% CI | (-−3.225; 8.503) | (−1.235; 2.666) | (−2.016; 1.425) | (−1.053; 2.206) | (−.059; 3.344) |

| Sig. | 0.376 | .471 | .736 | .487 | .058 |

| Level of Emotional Self-Management Training | |||||

| (t) | 2.177 | 1.324 | 1.326 | 1.577 | 3.126 |

| 95% CI | (0.66; 13.244) | (−0.69; 3.52) | (−0607; 3.104) | (−.35; 3.162) | (1.066; 4.701) |

| Sig. | 0.03 | .187 | .186 | .116 | .002 |

| Avoidance/transfer of care to others | |||||

| (t) | 1.653 | 1.47 | .836 | 2.19 | 1.066 |

| 95% CI | (−1.568; −17.903) | (−0.823; 5.658) | (−1.65;4.08) | (.299; 5.683) | (−1.309; 4.395) |

| Sig. | .1 | .143 | .404 | .03 | .288 |

| Considers depersonalisation a common feature of care | |||||

| (t) | 1.581 | 1.007 | 2.438 | .228 | 1.620 |

| 95% CI | (−1.108; 10.115) | (−.915; 2.828) | (.387; 3.651) | (−1386; 1.748) | (−.291; 2.985) |

| Sig. | .115 | .315 | .016 | .82 | .107 |

| Avoidance of contact with patient's family | |||||

| (t) | .801 | −.693 | .373 | 1.275 | 1.734 |

| 95% CI | (−4.966; 11.763) | (−3.76; 1.803) | (−1.989; 2.919) | (−1.051; 4.598) | (−.291; 4.568) |

| Sig. | .424 | .489 | .709 | .211 | .084 |

| Considers PC/MH support needed in HES | |||||

| (t) | 2.778 | 3.295 | 1.693 | 2.147 | 2.617 |

| 95% CI | (3.479; 20.448) | (1.518; 6.329) | (−.354; 4.670) | (.212; 4.957) | (.815; 5.778) |

| Sig. | .006 | .002 | .092 | .033 | .009 |

CLFDS: Collet-Lester Fear of Death Scale; 1-FOD: Fear of own death; 2-FDP: Fear of own dying process; 3-FDO: Fear of death of others; 4-FDPO: Fear of dying process of others; (t) Student's T-Statistic; 95% Confidence Intervals; Sig. Level of Significance; Cohabitation*: (Category 1: Lives with family/partners; Category 2: Lives alone); Children**: (Category 1: No children; Category 2: Yes children); PC: Palliative Care MH: Mental Health; HES: Hospital Emergency Service.

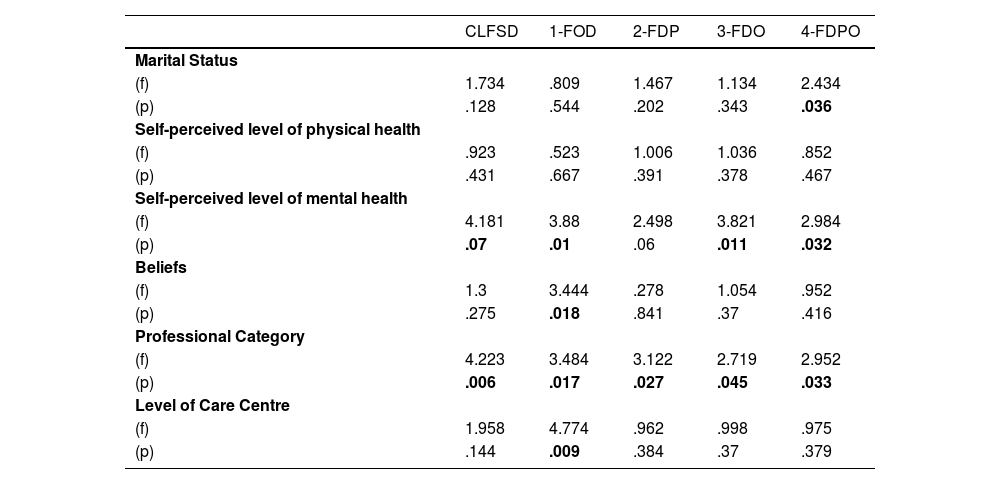

Results of the inferential analysis of the one-factor ANOVA statistic. Relationship between CLFSD, its subscales and qualitative variables with more than 2 categories in the sample.

| CLFSD | 1-FOD | 2-FDP | 3-FDO | 4-FDPO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital Status | |||||

| (f) | 1.734 | .809 | 1.467 | 1.134 | 2.434 |

| (p) | .128 | .544 | .202 | .343 | .036 |

| Self-perceived level of physical health | |||||

| (f) | .923 | .523 | 1.006 | 1.036 | .852 |

| (p) | .431 | .667 | .391 | .378 | .467 |

| Self-perceived level of mental health | |||||

| (f) | 4.181 | 3.88 | 2.498 | 3.821 | 2.984 |

| (p) | .07 | .01 | .06 | .011 | .032 |

| Beliefs | |||||

| (f) | 1.3 | 3.444 | .278 | 1.054 | .952 |

| (p) | .275 | .018 | .841 | .37 | .416 |

| Professional Category | |||||

| (f) | 4.223 | 3.484 | 3.122 | 2.719 | 2.952 |

| (p) | .006 | .017 | .027 | .045 | .033 |

| Level of Care Centre | |||||

| (f) | 1.958 | 4.774 | .962 | .998 | .975 |

| (p) | .144 | .009 | .384 | .37 | .379 |

CLFDS: Collet-Lester Fear of Death Scale; 1-FOD: Fear of own death; 2-FDP: Fear of own dying process; 3-FDO: Fear of death of others; 4-FDPO: Fear of dying process of others; (f): Value of the F-test statistic; (p): Probability of significance of the one-factor ANOVA statistic.

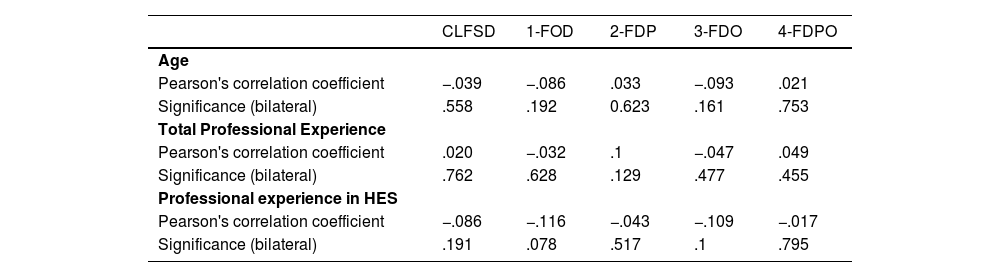

Results of Pearson's correlation test. Relationship between CLFSD, its subscales and quantitative variables in the sample.

| CLFSD | 1-FOD | 2-FDP | 3-FDO | 4-FDPO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| Pearson's correlation coefficient | −.039 | −.086 | .033 | −.093 | .021 |

| Significance (bilateral) | .558 | .192 | 0.623 | .161 | .753 |

| Total Professional Experience | |||||

| Pearson's correlation coefficient | .020 | −.032 | .1 | −.047 | .049 |

| Significance (bilateral) | .762 | .628 | .129 | .477 | .455 |

| Professional experience in HES | |||||

| Pearson's correlation coefficient | −.086 | −.116 | −.043 | −.109 | −.017 |

| Significance (bilateral) | .191 | .078 | .517 | .1 | .795 |

CLFDS: Collet-Lester Fear of Death Scale; 1-FOD: Fear of own death; 2-FDP: Fear of one's own dying process; 3-FDO: Fear of death of others; 4-FDPO: Fear of the dying process of others.

The results obtained for anxiety levels, measured with the CLFDS and its subscales, showed lower values than those found in studies in other care settings. Thus, in the study undertaken by Sevilla-Casado et al.20 in a sample of social and health care nurses, mean values of 114.3 were obtained for the CLFDS and 26.55, 30.09, 29.64 and 27.82 for the FOD, FDP, FDO and FDPO subscales respectively, indicating that a more continuous and prolonged exposure to death could explain the high levels of anxiety in these professionals. In another sample of nursing students undertaken by Ortego-Maté et al.,21 this also found higher mean levels on the CLFDS (102.88) and in each of its subscales: FOD (23.19), FDP (26.07), FDO (28.46) and FDPO (25.16). For these authors, the lack of strategies for coping with death gives rise to greater anxiety about the process in the most junior professionals. In studies undertaken in the HES environment, the levels of anxiety analysed showed highly variable data and have the limitation of not having used the same instrument. Thus, low and moderate levels of anxiety have been found on the “Fear of death Scale” in the samples of Shafaei et al.22 and Momeni et al.9 and other higher levels have been obtained with the Death Attitude Prolife instrument in a study by Peter et al.10 These authors point out how lower emotional involvement of emergency professionals may explain the lower values obtained in these settings. However, further study on the phenomenon is required to understand these differences between the different units, thus reinforcing the need to increase research in this field in the HES setting.

In our analysis, significant differences were found between the levels of anxiety according to gender. The literature points out that women tend to have higher levels of fear and anxiety about death, and they are also the majority gender in the healthcare professions.9,23,24 In this direction, in a study applied to a sample of nursing students Fernandez-Martinez et al.,25 found that women had significantly higher levels of anxiety about death, manifesting greater ease when expressing and admitting feelings on the subject of death. Coinciding with the findings of other authors, the differences in the attitude and approach to the death of patients between the genders may have a negative impact on women, since, although they cope more effectively with the process, they take on a greater emotional burden during the process, presenting higher levels of anxiety about death.26

Differences were found in the degree of anxiety and fear of death experienced by the different professional categories involved in that process. In the context of health emergencies, Sadhedi et al.27 also found different levels of fear of death among a sample of medical students and emergency healthcare personnel. Similarly, Nascimento-Santos et al.16 point out differences between students from different branches of the health sciences, relating these to the training content and care roles of each profession. In this regard, a training centred more on direct care and the needs of the individual in the nursing role, as well as a focus more centred on the healing, diagnosis and treatment of health processes in medicine, may explain the differences in the levels of anxiety about death between medical students and medical personnel in emergency services.

In our study, we found a significant association between the level of training in emotional self-management processes and the level of anxiety about death. This variable has been related to lower levels of anxiety in studies run on health personnel in palliative care units, oncology and health science students.23,28,29 On this point, Goris et al.30 observed a decrease in mean anxiety values after a training course to improve end-of-life care skills in a group of oncology nurses. Likewise, Philippon et al.31 observed a reduction in anxiety levels in emergency professionals through a training course based on simulations of patients dying in a critical situation in the unit, which enabled specific skills in communication and emotional control to be developed. These observations reinforce the hypothesis that training aimed at the management and self-management of emotions can favour the reduction of anxiety levels in these environments.

In the results obtained, the self-perceived level of mental health was related to anxiety about death. Previous research indicates that professionals with frequent and continuous contact with death develop a higher risk of mental illness.32 In particular, Shafaei et al.22 point out how not dealing with the death of different people can lead to disorders such as anxiety and chronic depression in the workplace which, in turn, has repercussions on the quality of care, in this case within the HES. Similarly, a significant association was found between the perceived lack of support from palliative care and mental health professionals and anxiety and fear of death. The results are similar to those reported by Lázaro-Pérez et al.23 in a sample of healthcare professionals from different hospitals in Spain at the beginning stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, pointing to the lack of psychological support as a determining factor in anxiety about death. These assessments highlight, for example, the importance of interdisciplinary support and its involvement in the anxiety levels of professionals.

Our results showed no significant differences between age and professional experience, as regards the values for fear of death. The results differed from those obtained in services where palliative care is frequent, with the newer professionals presenting higher levels of anxiety compared to those with more experience.10,33 For Nia et al.28 professional experience provides greater training to care for patients at the end of life, providing more experienced professionals with more effective coping strategies and presenting lower rates of avoidance of the dying process itself and towards the family. However, in samples from other HESs, the results coincide with those obtained in our analysis, with no differences being found between the variables of age and professional experience.6,27 Frequent coping with acute-critical deaths in emergency situations may generate a constant level of stress during care, thus giving rise to continued anxiety during the dying process, regardless of the age and level of training of the professionals.

LimitationsThe low response rate obtained in this study limits the representativeness of the sample and its external validity. Two factors may have influenced this. Firstly, professional fatigue during the pandemic, especially in the HES, may have reduced interest in participating. Secondly, death generates a certain rejection and avoidance among healthcare personnel and possibly greater participation among those professionals who are more interested in this particular subject. On the other hand, in order to compare the results obtained with those of other populations, the socio-demographic and healthcare differences between countries and environments need to be considered.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of fear of death among healthcare professionals in the HESs in Aragon is lower than that obtained in studies in other settings. Less prolonged and continuous exposure to death in the HES may explain part of these differences. Gender differences in anxiety values may be associated with a greater involvement in the process and the emotional burden in the case of women. The differences obtained between professional categories may be related to the perspective and coping skills specific to each discipline in the face of death. The level of training, self-perception of the state of mental health, and the lack of professionals in the area of support in this service were identified as determining factors in the degree of anxiety about death among professionals. Training in strategies for emotional management; personal and professional coping; conflict control and supportive care; and accompaniment at the end of life, are all highlighted as key strategies for improving end-of-life care in the HES.

FundingThis project is not funded by any external body outside the University of Zaragoza.

Conflict of interestThe authors of this manuscript declare that they have no conflict of interest in the preparation of this project. For the record, an affidavit is attached.

To the teaching team of the PhD course in Health and Sports Sciences at the University of Zaragoza. To all the department heads and nursing supervisors for their collaboration in the distribution and collection of the data.