Life satisfaction and quality of life of elderly people are still major issues in elderly residential care homes in West Sumatra. It is mainly caused by the low quality of services provided for the elderly in the care homes. Interventions are needed to overcome this problem by means of the role of nurses as advocacy with a cultural approach.

ObjectiveTo examine the effect of culture-based interventions on satisfaction and quality of life in elderly people from Minang culture background.

MethodThis research used quasi-experimental design, or pre–post intervention design, with a total sample of 76 elderly people. They were divided into 38 people for each intervention and each control group. Data were analyzed using general linear model-repeated measures.

ResultsThere was the difference in life satisfaction and quality of life of the elderly in the PSTW (state-run nursing homes) before and after the intervention both in the intervention group and the control group (p<0.000).

ConclusionsCulture-based interventions were effective to increase the satisfaction and quality of life of Minang elderly people.

An increasing of Indonesia's elderly population in 2016 reached 8.65% of the total population of Indonesia, with a dependency ratio reaching 13.65 and a morbidity rate of 27.46%.1 This condition causes an increase in the number of neglected elderly people which has reached 2.1 million people nationally and 1.8 million more people potentially become neglected. The protection given to the elderly has only reached 0.77% (30,000 persons) out of the 3.9 million neglected and potentially neglected elderly.2 Nationally, the percentage of elderly in West Sumatra is 9.27% of the population, the dependency ratio is 14.80, and morbidity rate is 27.83%.1 Neglected elderly in West Sumatra reach 41,259 people, only 250–300 (0.5%) people are accommodated in social welfare institution (Panti Sosial Tresna Werdha [PSTW]).3,4 Some studies identify the elderly who live in institutions are mostly without spouses, sickly, without caring from family, not having children, and having family conflicts.5,6

West Sumatra is a province with the largest matrilineal kinship system in the world. In this kinship system, the elderly become the responsibility of the daughters.7 However, the transformation in the cultural values makes this kinship system is not implemented well, because offspring tend to prioritize their main families, and daughters start their careers to help to fulfill the needs of the main family,8 so that the elderly are at risk of being neglected.5,7,8 Elderly seek shelter out of their kinship systems like living in an institution for elderly people in hopes of getting more satisfying and good quality of life.

The quality of life of the elderly is affected by the limitations of their participation in activities, negative views on life, lack of hope, dissatisfaction with their lives, and depression.5,9–11 If life satisfaction is achieved, the quality of life will be able to be maintained.12 Around 63.4% of the elderly are dissatisfied with their life in PSTW, 52.4% of the life quality of the elderly is low, 54.5% have symptoms of depression, and 50% of the elderly in PSTW Sabai Nan Aluih are at depression risk.5,9 This happens because reality does not match expectations, their health declines, and they have a lack of autonomy in doing activities. Depression in the elderly begins with dissatisfaction with life while they live in an institution. This condition poses a risk of low quality of life for the elderly as a result of the built expectations that are not achieved.11 A prior study found that there were more male occupants in institutions.6 This occurs because the matriarchal system gives the impression that children have less care for the father, while taking care of the mother is taken as an obligation. The influence of their past as migrant workers is very visible in the elderly who were previously successful abroad. Success causes them to be lacking of care for relatives so that when they are old, their relatives, especially their nephews, ignore them.8

Life in nursing homes does not always satisfy the elderly. Elderly people feel unappreciated by the behavior of caregivers, such as not listening to the demands of the elderly, moving the elderly to another lodge without explanation, always assuming the elderly who live in the institution have problems, and often giving commands regardless of the capabilities of the elderly. These situations make the elderly do not dare to talk much, become stressful, and have symptoms of depression.13 This is contrary to the cultural values of Minang which highly value the position of the elderly as a respectable person.14 The shift in Minang's cultural values needs to be restored so that the elderly feel comfortable and secure when they live in nursing homes. Culture-based hope intervention is the key to restoring new hope to the elderly during their stay in this institution. Hope is an emotion directed by thought and influenced by environmental conditions and is the ability to plan solutions to achieve goals and make obstacles as motivations.15,16 This research aims to examine the effect of hope intervention by means of Minang cultural approach toward the changes in satisfaction and quality of life for elderly people in social welfare institution.

MethodThis research used a quasi-experimental design, or pre–post intervention design, with a control group. The research was conducted for 6 months at the PSTW owned by the West Sumatra government. The research population was all elderly who lived at PSTW in West Sumatra, namely, PSTW Kasih Sayang Ibu and PSTW Sabai Nan Aluih. These two institutions were chosen because they fulfilled the criteria, including the elderly living there are not severely depressed, not seriously ill, not senile, and able to hear well enough. Sample size referred to the results of previous studies that were almost similar to the variable of life satisfaction with the hope intervention, which was: SD=7.09, μ1=19.44, μ2=17.68.16 The sample size for this research used the hypothesis test of mean differences in two independent groups with a significant degree of 95% (Z1−α/2=1.96) and the test power of 80% (Z1−β=0.84).17 A sample of 38 people for each intervention and control group was obtained. Samples were taken randomly from the total number of elderly people who met the criteria in each PSTW.

The instruments used were demographic instruments; Herth expectation index; life of satisfaction index-A (LSIA) (reliability 0.880 and validity 0.396–0.536); WHOQoL-BREF (0.949 reliability and validity 0.369–0.672).6 Data were analyzed using the general linear model-repeated measures (GLM-RM)17 test because of the repeated data collection.

Cultural-based interventions included Researching for Hope, Connecting with Other, Spiritual Transcendental Process, Development for Hope and Maintenance for Hope (RECONNECT-SDM) designed using the approach of Minang culture that integrated the values and characteristics of the Minang people, such as saiyo sakato (unanimous), sahino samalu (feeling united/empathy), anggo tango (following agreed rules and code of conducts) and sajinjiang sapikua (to share one's joys and sorrows) in intervention activities.8,18 Therapeutic communication is integrated into the communication principle of Minangkabau people “kato nan ampek” (the words of four) in the interaction of the elderly with facilitators and fellow elderly.19 Research activities were assisted with a hope intervention guidebook.

Implementation of culture-based interventions is as follows: (1) group meetings or individual meetings with the elderly to explore missing experiences and life expectancies with the help of facilitators who wrote on paper; (2) bringing the elderly to establish social interactions with the caregivers and other elderly people at each institution activity and to establish the pre-arranged agendas, for example, inter-lodges visits; exchanging religious knowledge, and helping elderly who had weaknesses; (3) second meeting in groups or individuals to reorganize the desires that have been identified from the prior activities. (4) helping the elderly to organize steps to achieve new hopes and build a commitment to achieve these hopes with help from facilitators at the institution; (5) in the third month, the elderly accompanied by facilitators carried out activities that mutually agreed with.

ResultsThe average age of respondents was 74.39 years old. Most of them were men (63.2%), with 71.1% were widows or widowers, and 84.2% had a low education level (elementary school, junior high school, or even without education). The reason for staying in an institution was because of their own wishes (69.7%). From 38 respondents, 81.6% had stayed in the institution for less than or 10 years. The average index of expectation was 20.16 from the highest index of 48. There was no difference in the distribution of respondents’ characteristic data among groups or in other words, there is homogeneous data distribution.

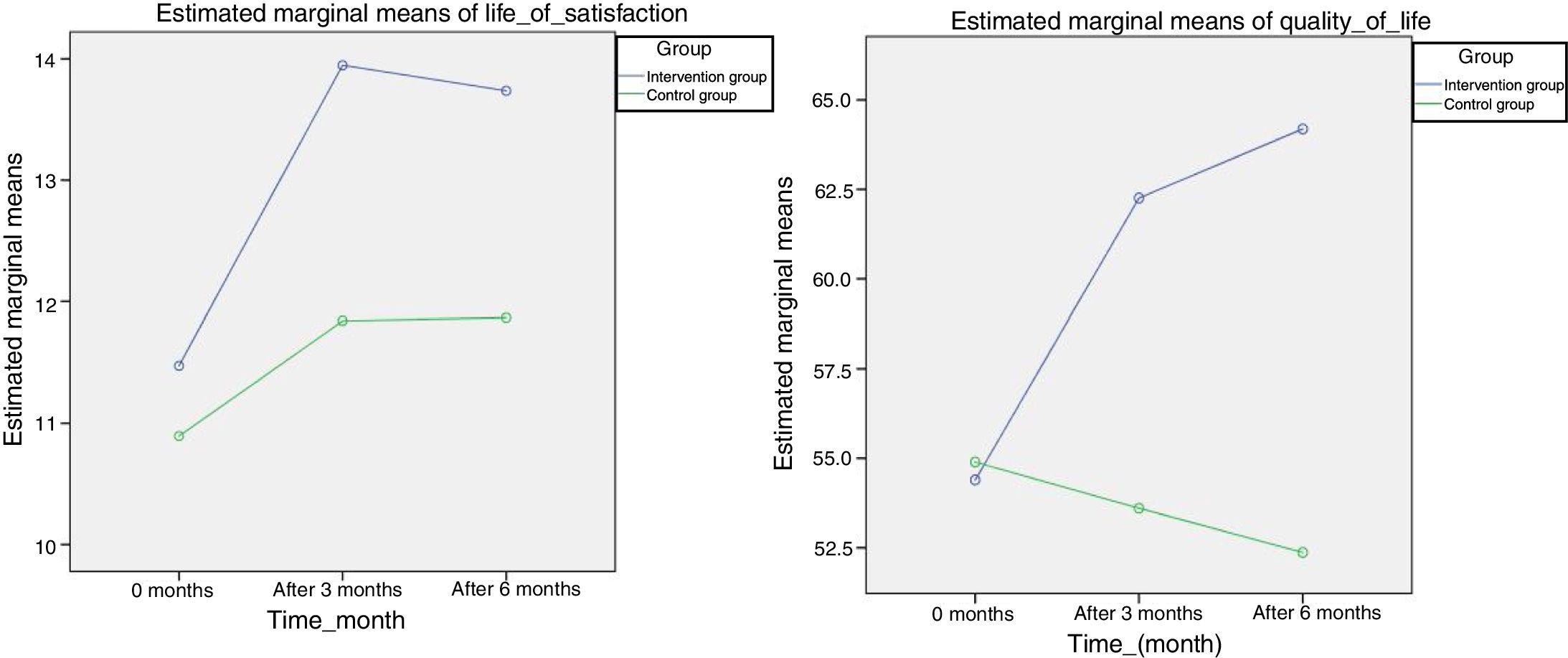

Table 1 shows an increase in the average of life satisfaction before and 3 months after the intervention, both in the intervention and the control group. The table also shows a decrease in the average of life satisfaction 6 months after the intervention. There was no difference in the mean score of the life satisfaction of the elderly before the hope intervention both in the intervention group and the control group, with p-value=0.394. However, the measurement of 3 and 6 months after the intervention found differences in the life satisfaction of the elderly in the control group and the intervention group (p<0.000).

Life satisfaction of the elderly before and after hope intervention between intervention and control group in West Sumatra PSTW (n=76).

| Variable | Intervension group (n=38) | Control group (n=38) | p-Value | Difference | CI (95%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | CI (95%) | Mean | CI (95%) | ||||

| Life satisfaction | |||||||

| Before | 11.39 | 10.73–12.06 | 10.97 | 10.31–11.64 | 0.394 | 0.42 | −0.56 to 1.39 |

| After (3 months) | 13.87 | 13.35–14.39 | 11.91 | 11.39–12.44 | 0.000 | 1.95 | 1.18–2.72 |

| After (6 months) | 13.77 | 13.06–14.47 | 11.84 | 11.14–12.54 | 0.000 | 1.93 | 0.90–2.96 |

| p interaction=0.013; R2=0.058 | |||||||

The difference in life satisfaction between before and 3 months after the intervention (p=0.000, R2=0.328).

The difference in life satisfaction between 3 months and 6 months after the intervention (p=0.001, R2=0.173).

When measurement times were, there were differences in the life satisfaction of the elderly before and after 3 months of intervention (p=0.000) with the different strength of 32.8% and between 3 and 6 months after the intervention (p=0.001) with the different strength of 17.3%. This means that culture-based hope can improve the life satisfaction of the elderly after 3 months of intervention.

Table 2 shows that the average quality of life of elderly people increases after hope interventions in the intervention group, and decreases in the control group. Before the intervention, statistically, there was no difference in the quality of life of the elderly both in the intervention and the control group (p=0.814). Measurements were done in 3 and 6 months after the intervention. Statistically, differences were found in the quality of life of the elderly both in the intervention group and the control group (p=0.000).

Differences in the quality of life of the elderly before and after the hope intervention between intervention and control groups in West Sumatra PSTW (n=76).

| Variable | Intervention group (n=38) | Control group (n=38) | p-Value | Difference | CI (95%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | CI (95%) | Mean | CI (95%) | ||||

| Quality of life | |||||||

| Before | 54.4 | 51.5–57.3 | 54.9 | 52.0–57.8 | 0.814 | 0.5 | −4.7 to 3.7 |

| After (3 months) | 62.3 | 60.2–64.4 | 53.6 | 51.5–55.7 | 0.000 | 8.7 | 5.6–11.7 |

| After (6 months) | 64.2 | 61.6–66.8 | 52.4 | 49.7–55.0 | 0.000 | 11.8 | 7.9–15.7 |

| p interaction=0.000; R2=0.219 | |||||||

The difference in the quality of life between before and 3 months after the intervention (p=0.000, R2=0.402).

The difference in the quality of life between 3 months and 6 months after the intervention (p=0.001, R2=0.395).

When measurement times were compared, there was a difference in the quality of life of the elderly 3 months after the intervention (p=0.000), the power of differences was 40.2%. Differences in quality of life were seen from measurements 3 months after the intervention compared to measurements 6 months after intervention (p=0.000) with the power of differences was 39.5%. Graphically, the development of satisfaction and quality of life of the elderly can be seen from 3 measurements in Fig. 1.

DiscussionsDifferences in life satisfaction of Minang elderly in the intervention group and the control groupsThe results showed that life satisfaction increased in the measurements 3 months after the intervention but decreased 6 months after intervention in the intervention group. The hope intervention in this study was given using the Minang culture approach, and was proven to increase the satisfaction of a life of the elderly in the nursing homes. The results of this study are in line with some of the results of research conducted by other researchers.15,16,20 The hope intervention given with a positive psychological view approach,15 given in groups,16 can improve the life satisfaction of the elderly in the nursing home, although it is lower than changes in positive perception of the elderly toward aging.20 This result is different from the results of Wilson's research,21 which states that hope intervention does not have an effect on the life satisfaction of the elderly. This happens because the time to grow hope is only 30 days (1 month), with varying levels of depression. Besides, hope intervention is not designed more specifically with a cultural approach for the elderly with depression.

Interventions are designed with Minang culture approach, especially therapeutic communication used by facilitators so that the elderly feel that they are valued and cared for. The principle of kato mandaki (the word-climbing) is part of langgam kato nan ampek (the four-word pattern). It is a way of communication to explore the experiences and life expectancies of the elderly who may not be pleasant to talk about. The life satisfaction of the elderly can be influenced by short, clear, simple communication, and positive, non-suppressive or authoritarian words.22 Meanwhile the elderly expected that there would be not too many rules, they can earn more respect, and their wishes are taken seriously. The elderly in Minang are people who must be respected, and existed in the social etiquettes in Minang in the form of proverb yang gaek dihormati, yang ketek disayang (those who are old are respected, the young are cherished).

There are factors that support the success of the intervention, such as the fact that the reason of most of the elderly living in the institution is due to their own desires, less than 10 years living in the institution, and their involvement in group activities. Interesting things about the satisfaction conveyed by the elderly and that needs to be maintained are: 97.4% of the elderly feel satisfied with the positive things they have now because the basic needs of the elderly, such as eating and resting, are fulfilled well compared to before living in the institution. However, the elderly really need attention and appreciation from facilitators. After getting the intervention, 93.4% of the elderly felt satisfied with the exciting activities that previously did not exist although more than half of the elderly said they were old and began to get tired of sitting too long.

The decline in life satisfaction of the elderly at measurements 6 months after the intervention occurred because caregivers were not in the nursing homes, activities were not routinely and did not vary, so that the elderly were bored, the caregivers used authoritarian communication, hard intonation, discriminated the elderly and they worked only due to obligation.22 Caregivers’ interaction with the elderly was only 10.7% of the time the caregivers spent in the nursing home, so it needed a variety of scheduled activities. Caregivers who are not at the nursing homes become a factor in the low life satisfaction of the elderly in the control group. Caregivers work more on activities that are not their responsibility, which results in the caregivers not knowing the health condition of the elderly at their care house. This happens because nurses and social workers are appointed by the government without first going through professional training.

Differences in quality of life of Minang elderly in the intervention group and the control groupsThe results showed that culture-based hope interventions improved the quality of life of the elderly. It can be seen from measurements 3 months and 6 months after the intervention was implemented. The results of this study are in line with several other studies conducted by researchers who provide hope intervention in the elderly.21,23–25 This intervention in groups, was proven to improve the quality of life of the elderly.23 Besides, it can motivate the elderly to explore the hopes of their life experiences, so they feel alive because they found out that it is not too late for elderly people to have hope.25 This intervention can reduce pain, which is one component of improving the quality of life.23,24 Hope intervention has a strong effect on improving the quality of life of the elderly by 79% (p<0.001). Although the power of the effects in the Madadi and Sodani study was greater than it is in this study, the intervention was expected to improve the quality of life for the elderly.

The difference in the quality of life of the elderly before and after receiving hope interventions continued to increase, although the increase in the 6th month after the intervention was not too high. This happens because there is very little variation of activities from the facilitators, low cultural competence, especially awareness and culture knowledge of caregivers.26 Quality of life is a force that provides guidance, maintains and improves health, therefore a caregiver must expand the scope of knowledge about beliefs, values, and socio-cultural patterns of certain groups of people.27 Interventions to improve the quality of life of the elderly require special attention and approaches in accordance with the socio-cultural values of the elderly. Although the respondents in this study were homogeneous, cultural similarities, values, and destiny should be a major contribution to enhance new relationships in the institution.28,29 These are the values that are owned by Minang community, which become an approach to hope intervention, namely, saiyosakato (unanimous) and sahinosamalu (feeling united/empathy).18

In contrast, the quality of life of the elderly in the control group continued to decline, especially in the aspect of social dimension with an average of only 50.66%. Identifying the theme of social change is one of the dimensions of the quality of life in the elderly in the institution13; The identified sub-themes, conflicts between fellow elderly people and caregivers, as well as the low level of togetherness and empathy of fellow elderly and caregivers. This happens because of the lack of communication and interaction between facilitators and the elderly. Interaction of facilitators who care for the elderly in the institution can be in the form of creating a homely atmosphere with humor, telling each other daily activities, and laughing together.30 This situation shows the caregiver's attitude that is focused on the elderly so that positive interactions will be formed.31–33 Inadequate interaction through effective communication makes the elderly feel lonely and less enthusiastic about doing activities. This will lead to passive attitudes and can result in physical and psychological complaints that can decrease the quality of life.

Culture-based hope interventions have been proven for their effectiveness in increasing the satisfaction and quality of life of the elderly in nursing homes. Interventions can be implemented in elderly care institutions, but further research is still needed concerning the application of these interventions in other cultures by adjusting cultural values and ways of communication. The increase regarding satisfaction and quality of life of the elderly is not too large, but cultural-based interventions can be an alternative activity to foster hopes so that the quality of life gets better. Interventions can be developed in accordance with the conditions and circumstances of the elderly. They can take different forms, such as physical training, hope training, and health education to promote health. Culture-based interventions encourage facilitators, especially nurses, to get to know the culture of the elderly by increasing their cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, and cultural skills in where they work.

ConclusionsAfter receiving hope-based intervention based on culture, satisfaction and quality of life of the elderly in the intervention group were better than in the control group. This intervention has been proven effective to improve the satisfaction and quality of life of the elderly at PSTW. Caregivers need to spend more time and improve the quality of interactions with the elderly. Support and creativity from caregivers are also needed in choosing the form of cultural-based intervention and in applying communication patterns kato nan ampek (the four-words pattern), so that the value of sahinosamalu (feeling united/empathy), rasojopareso (the intelligence of heart and feeling) between fellow elderly who live in institutions, between the elderly and facilitators, and between the elderly and caregivers, are born. Cultural approaches can be used as an alternative effort for nursing institutions in any country to increase the satisfaction and quality of life of the elderly in accordance with their socio-cultural context.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

This work is supported by Hibah PITTA 2018 funded by Universitas Indonesia No. 1846/UN2.R3.1HKP.05.00/2018.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the Second International Nursing Scholar Congress (INSC 2018) of Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia. Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.