It is not uncommon for new nurses to experience dissatisfaction and underperformance in their professional practice as a nurse in their first year on the job. In this transitional phase, new nurses need a preceptor to guide them. The provision of preceptor guidance with caring value and support for new nurse self-efficacy is a critical element that new nurses require. This study aimed to analyze the relationship between caring preceptor, self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and the performance of new nurses.

MethodThe research method used a cross-sectional design based on a sample set of 123 new nurses selected using the total population sampling method. Data were analyzed using correlation testing and multiple linear regression.

ResultsThe results showed that there was a strong correlation between a caring preceptor and job satisfaction (r=0.522, p=0.0001) and new nurse performance (r=0.572, p=0.0001). There was a moderate correlation between self-efficacy with job satisfaction (r=0.371, p=0.0001) and new nurse performance (r=0.240, p=0.008).

ConclusionFor new nurses, the presence of a caring preceptor and self-efficacy are predictors of job satisfaction and performance. The preceptor had to care, which contributed to increasing the self-efficacy of new nurses.

New nurses face many challenges during the first year of work, which impacts on job satisfaction and job performance. The new nurse feels nervous, anxious, tired, unconfident, and under stress in the workplace in the first year of work.1 New nurse job satisfaction and job performance are influenced by many factors, with two key factors being the caring of the preceptor2,3 and self-efficacy.4

The first influencing factor, caring of the preceptor, is defined as the positive relationship between the preceptor and new nurse based on Watson's Theory of Caring.3 According to Kelly and McAllister, the relationship between preceptor and the new nurse has a positive effect on the new nurse's adaptation to the workplace.5 The new nurses will be readily adaptable to the workplace if they have a good relationship with the preceptor.3

The new nurse requires psychosocial and interpersonal support. Such support will be realized if the preceptor applies caring behavior to the new nurse. Watson's Theory of Human Caring states that humans have psychosocial and interpersonal needs.6 Confident and caring relationships are critical to help new nurses who feel anxious, fearful, under pressure, and face a difficult adaptation from being nursing students to a professional nurse.2,3,6–9

The caring behavior of the preceptor establishes the relationship between the preceptor and the new nurse.10 The caring of the preceptor can increase the job satisfaction, quality of work, and patient safety of the new nurse. According to Kim et al., good relationships will increase the confidence and competence of new nurses.11

The job performance and job satisfaction of new nurses are influenced by having self-efficacy. High self-efficacy makes nurses more adaptable to their work environment.4 Most of the new nurses have low self-efficacy, which decreases the quality of nursing care services. Furthermore, the new nurse's self-efficacy determines her or his response to solving a problem.4

Self-efficacy affects nurse performance and job satisfaction. According to Judge et al., there is a relationship between self-efficacy and nurse performance.12 Wilson and Byers stated that there is a relationship between self-efficacy and nurse job satisfaction.4 The results of this study indicate that high self-efficacy can improve the satisfaction and performance of nurses.

It is possible new nurses will decide to leave their job if the period of nursing orientation proves too stressful. The caring of the preceptor and new nurse self-efficacy are very important to develop the quality of nursing care, to help the new nurse feel part of the nursing team, reduce anxiety, fear, and stress, and improve nurse retention.

The purpose of this article was describing the relationship between caring preceptor, self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and the new nurse performance.

MethodA quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive design was used. The sampling technique used total population sampling. Research respondents were 123 new nurses. The inclusion criteria were nurses with a working period of 6–24 months, have been following the preceptorship program, not being on leave or sick, and willing to be respondents.

The researcher-designed demographic questionnaire included questions about age, gender, marital status, education level, and employment area. The Caring Preceptor Scale, which was also developed by the researcher, was used to measure the caring of the preceptor. Content validity was established through a literature review and subject matter experts. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was reported as 0.821. The researcher established the Self-Efficacy Scale. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was reported as 0.729. The New Nurse Performance Scale, which consisted of 30 items, was established with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.918. The New Nurse Job Satisfaction Scale, which consisted of 20 items, was modified with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.899.

Ethical approval was obtained from the university's institutional review board and the hospital research committee. Informed consent was presented to each new nurse to explain the purpose of the research study. Completion of the surveys implied consent. All of the respondents involved in the study were kept confidential. All data were stored and used for research purposes.

Data were analyzed using a statistical program. Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations) were performed to describe the sample characteristics, and each new nurse's perceived caring of the preceptor, self-efficacy, performance, and job satisfaction. Correlation analyses were conducted to examine the relationships between caring preceptor, self-efficacy, new nurse performance, and job satisfaction. Stepwise multiple regression analysis was conducted to determine whether a caring preceptor and self-efficacy were predictors of job satisfaction. Finally, stepwise multiple regression analysis was performed to determine whether a caring preceptor, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction were predictors of new nurse performance. An alpha value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsThe average age of new nurses in the study was 25.14 years with the youngest being 21 and the oldest being 42 years. In Jakarta Central General Hospital, the majority of the new nurses were female (93; 75.6%), mostly educated with a diploma (86; 69.9%), and mostly unmarried (87; 70.7%), though a minority worked in the ER (50; 40.7%) (Table 1).

New nurses characteristics based on age, gender, education level, marital status, and employment area at Jakarta Central General Hospital, May 2018 (N=123).

| Characteristics | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 25.14 | 3.132 |

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 30 | 24.4 |

| Female | 93 | 75.6 |

| Education level | ||

| Diploma | 86 | 69.9 |

| Bachelor | 37 | 30.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 35 | 29.3 |

| Unmarried | 87 | 70.7 |

| Employment area | ||

| Inpatient Room (IR) | 21 | 17.1 |

| Emergency Room (ER) | 50 | 40.7 |

| Surgery Room (SR) | 38 | 30.9 |

| Intensive Care Unit (ICU) | 14 | 11.4 |

The average caring of the preceptor as perceived by the new nurse was 105.83 or equal to 73.5% of the maximum value. The average self-efficacy of the nurse was 17.55 or equal to 71.3%. The average performance value of new nurses was 101.03 or equal to 84.2%. The average new nurse satisfaction score was 60.76, which was equivalent to 60.76% (Table 2).

Caring preceptor, self-efficacy, new nurse performance and job satisfaction at Jakarta Central General Hospital, May 2018 (N=123).

| Variable | Mean | Min–Max | SD | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caring preceptor | 105.83 | 72–143 | 14.989 | 105.8–111.18 |

| Self-efficacy | 17.55 | 12–24 | 2 | 17.20–17.91 |

| New nurse performance | 101.03 | 69–120 | 10.823 | 99.10–102.96 |

| Job satisfaction | 60.76 | 28–97 | 13.057 | 58.43–63.09 |

The result of the analysis determined that there was no relationship between new nurse characteristics with job satisfaction (Table 3). No statistically significant relationship was found between age with job satisfaction, with r=−0.041 (Table 4). A statistically significant correlation was found between having a caring preceptor and job satisfaction. New nurses assigned to a caring preceptor had a healthy, positive relationship with job satisfaction. A statistically significant relationship was found between self-efficacy and job satisfaction. Self-efficacy had a profound, positive relationship with job satisfaction (Table 4).

The relationship between new nurse characteristics based on gender, education level, marital status, and employment room with job satisfaction at Jakarta Central General Hospital, May 2018 (N=123).

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 30 | 61.37 | 14.383 | 0.770 |

| Female | 93 | 60.56 | 12.677 | |

| Education level | ||||

| Diploma | 86 | 61.13 | 13.541 | 0.632 |

| Bachelor | 37 | 59.89 | 11.989 | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 35 | 60.23 | 12.661 | 0.779 |

| Unmarried | 88 | 60.97 | 13.276 | |

| Employment area | ||||

| IR | 21 | 57.14 | 9.896 | 0.338 |

| ER | 50 | 61.26 | 12.804 | |

| SR | 38 | 60.42 | 14.259 | |

| ICU | 14 | 65.29 | 14.424 | |

No statistically significant relationship was found between new nurse characteristics (gender, education level, marital status, and employment area) with new nurse performance (Table 5). The lowest performance of the new nurses was in the ER=99.90 or equal to 83.25% while the highest performance was in the ICU=101.50 equal to 84.5%. The results obtained the p-value=0.625, which means there was no relationship between employment site with new nurse performance (Table 5).

The relationship between new nurse characteristics based on gender, education level, marital status, and employment room with new nurse performance at Jakarta Central General Hospital, May 2018 (N=123).

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 30 | 102.37 | 12.933 | 0.440 |

| Female | 93 | 100.60 | 10.091 | |

| Education level | ||||

| Diploma | 86 | 101.77 | 11.020 | 0.253 |

| Bachelor | 37 | 99.32 | 10.290 | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 35 | 101.91 | 9.690 | 0.571 |

| Unmarried | 88 | 100.68 | 11.275 | |

| Employment area | ||||

| IR | 21 | 100.14 | 9.946 | 0.625 |

| ER | 50 | 99.90 | 11.762 | |

| SR | 38 | 100.60 | 10.236 | |

| ICU | 14 | 101.50 | 10.552 | |

No statistically significant relationship was found between age and new nurse performance (Table 6). A statistically significant relationship was found between caring preceptor and new nurse performance. Having a caring preceptor had a healthy, positive relationship with new nurse performance. A statistically significant relationship was found between self-efficacy and new nurse performance. Self-efficacy had a profound positive relationship with new nurse performance (Table 6).

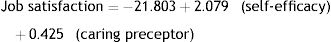

The results of multiple linear regression analysis are shown in Table 7 to give the regression equation obtained based on the value of the coefficient B test analysis.

Multiple regression examining the relationship between caring preceptor, self-efficacy, job satisfaction and new nurse performance.

| Job satisfaction | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | Beta | R | R2 | p value |

| Constant | −21.803 | 10.259 | 0.610 | 0.372 | 0.036 | |

| Self-efficacy | 2.079 | 0.475 | 0.319 | 0.000 | ||

| Caring preceptor | 0.425 | 0.063 | 0.487 | 0.000 | ||

| New nurse performance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | Beta | R | R2 | p value |

| Constant | 40.619 | 8.539 | 0.599 | 0.359 | 0.000 | |

| Self-efficacy | 0.976 | 0.398 | 0.180 | 0.016 | ||

| Caring preceptor | 0.399 | 0.053 | 0.552 | 0.000 | ||

The meanings of the regression model equation were: (1) Every single point increment of self-efficacy would improve new nurse performance by 0.976 after being controlled by caring preceptor; (2) every single point increment of a caring preceptor would improve new nurse performance equal to 0.399 after being controlled by the self-efficacy variable; (3) both caring preceptor and self-efficacy were significant predictors at 35.9% of the variance in new nurse performance, and (4) the most influential variable in new nurse performance was a caring preceptor.

The meanings of the regression model equation were: (1) Every single point increment of self-efficacy would improve job satisfaction by 2.079 after being controlled by a caring preceptor; (2) every single point increment of a caring preceptor would improve new nurse performance equal to 0.425 after being controlled by the self-efficacy variable; (3) both caring preceptor and self-efficacy were significant predictors at 37.2% of the variance job satisfaction, and (4) the most influential variable in new nurse performance had a caring preceptor.

DiscussionThe results showed that there was no correlation between nurse characteristics and job satisfaction and new nurse performance. These results are not as aligned as those obtained by Suryanto et al., who found that ages up to 35 years old were periods of high-performance capabilities for nurses, whereas older people were physiologically susceptible to fatigue.13 Nurse performance directly affects the quality of health care. The work of the staff nurse contributes directly to the quality of the services for the client. Work motivation is one of the factors that influence the work of a nurse. This research is a descriptive, quantitative, cross-sectional design that aimed to identify the relationship between the work motivation factors with staff nurse performance inpatient wards. The research used proportionate random sampling, which fulfilled an inclusion criterion; the study sample consisted of almost 100 staff nurses at inpatient wards. The research result identified three sub-variables of work motivation that related significantly to nurse performance, including interpersonal relations (OR=4.345), supervision (OR=72.952), and incomes or salary (OR=7.304). While the individual characteristic variable indicated two variables, performance is the education of staff nurse (OR=7.567) and age (OR=25.948). A dominant sub-variable connected with staff nurse performance was supervision (OR=72.952), after it was controlled by variables of age, income, or salary and education level. The increase of supervision by the head nurse, nursing committee, and nursing section needs to be improved, preferably by the approach of an organizational structure to motivate the performance of nurses.

There was no significant difference between the performance and satisfaction of male and female nurses. This result may be because the proportion of females is far more than males so it cannot describe the overall comparison of new nurse performance and job satisfaction between male and female nurses. The results of this study supported the research undertaken by Zahara et al., who stated there was no relationship between gender and nurse performance.14

Marital status had no relationship with performance or satisfaction. The researcher's opinion is that every new nurse would give her or his best to provide nursing care regardless of marital status. Although there was no correlation between educational level and new nurse satisfaction, the researchers found that the performance and satisfaction of nurses with a diploma degree was better than bachelor degree nurses. Dissatisfaction occurs due to a lack of autonomy and lack of career clarity.15

The low level of satisfaction associated with the high expectations of bachelor degree nurses appears to be inconsistent with the reality at work.15 New nurses received minimal information related to the career ladder in the hospital. This opinion supported the results of the questionnaire distribution that the item of opportunity to develop received the second-lowest total value. These results were in line with the research undertaken by Afriani et al.16, who stated the lower expectations were those of the new nurse.

New nurses with non-civil service employment status who were less exposed to information about the career ladder tended to have a perception of the career ladder that had less of a result on a decrease in performance.15,17 Increased knowledge of the career ladder, in contrast, will develop positive nurse behavior.18

There was no significant relationship between the employment area and new nurse performance and job satisfaction. The researcher saw that the lowest average performance value was in the ER. New nurses who are in the ER face varied and complex cases that they have never met before as a student, so new nurses are required to be able to provide nursing care according to predefined standards.19 Given the complexity and intensity of the ER, the guidance that new nurses were able to get from their preceptor was minimal.

The relationship between caring preceptor, self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and new nurse performanceThe preceptor was the key in the preceptorship program. The caring behavior of the preceptor established a relationship with the new nurse. It increases satisfaction and improves competence and performance. As stated by Kim et al.,11 a good relationship will increase the level of confidence and competence of a new nurse and is one of their primary needs.

During the transition period, having a positive relationship with their preceptor will better enable new nurses to overcome the problems of stress they experience and further the development of professional skills and personal development, such as communication and clinical ability.20,21 Caring preceptor behavior is best manifested as a role model for new nurses. In the ideal case, every dimension of care performed by the preceptor becomes the standard in the judgment of the new nurse.

The humanistic altruistic dimension focused on how to establish relationships between the preceptor and the new nurse as expressed in body language, intonation, open attitude, and facial expression.3 Its manifestations were of the preceptor as a role model, behaving professionally, adding value to the nursing culture within the organization, influencing new nurses, and contributing to the organizational strategic plan.3 Being exposed to positive preceptor roles improves the new nurses’ performance and job satisfaction.

With growing confidence, the new nurse will perform with the best possible skills in the workplace.3,22 To be optimistic, new nurses need positive motivation from the preceptor. Consequently, new nurse optimism can improve the performance of nurses in nursing care.

The next aspect of the caring dimension we will consider concerns the consciousness of self and others. It was evident one function of the preceptors was to understand the role they played in providing nursing care, as well as that of the patients, and new nurses.23 Based on this understanding of how the work environment best functioned, the preceptors contributed to making new nurses feel comfortable in the workplace. This dimension also relates to the attitude of the preceptor in providing support to new nurses.

The questionnaire distribution results for the caring dimension, which consists of developing mutual trust and attitudes, was the second-highest average value perceived by the new nurse. This result suggested that the preceptor role well manifested caring behavior to the new nurses. New nurses had a few nursing skills and often encountered obstacles.19 The trusting relationship between the preceptor and the new nurse enhanced positive feelings. The positive relationship started with communication. The preceptor had to be empathetic and friendly toward the new nurses. Empathy means the nurse could understand what the new nurse was feeling. Positive acceptance of others was meant in a friendly way and was expressed through body language, speech sound pressure, open attitude, facial expressions, and others.3

The result of the dimension, acceptance of positive or negative expression, was the lowest average value of all existing aspects. Caring preceptor behavior, in this case, consisted of being a good listener and paying attention to the feeling and sincerity of the new nurses. Preceptors gave their time to listen to new nurse problems.2,3 Caring preceptor behavior will affect job satisfaction. The preceptors who were able to manifest caring behavior made the new nurse feel comfortable in conveying the obstacles she or he faced during the workplace, which enabled them to work together until the problems could be solved.

One challenge of the new nurse is to solve problems systematically. The preceptor provides a problem for the new nurse to solve.24 In appropriate cases, the preceptor listens to the needs of the new nurse and solves the problem. Problem-solving begins when the preceptor identifies the needs of the new nurse, then plots the clinical guidance activity and evaluates the performance of the new nurse.2,3,25 Systematic problem-solving can be a self-evaluation element to improve new nurse performance. The preceptor can then evaluate the job progress of the new nurse.

The next caring dimension, improvement in interpersonal learning, is determined by the ability of a preceptor to create a productive climate for the learning process.26 The learning environment must be provocative, disciplined, fun, and humanistic through support and care. The preceptor views the new nurse as someone who still needs guidance to learn and can identify the appropriate learning method for the new nurse.26 The accurate identification of the learning methods offers a more relaxed way for the new nurses to learn, and to capture and reserve information more efficiently, reduce anxiety more immediately, and more effectively inhibit undesired conditions.

The manifesting of the next caring dimension, the provision of the physical, mental, socio-cultural, and spiritual environment, should not guide the new nurse dominantly unless safety is a concern. The purpose of providing a suitable environment is to conduct and identify the clinical situation. This pattern allows new employees to feel more confident.3 The provision of a comfortable environment starts with good organizational communication, which has a significant relationship to the improvement of new nurse performance.27

Accomplishing basic needs as a new nurse is fundamental to the preceptorship process. The preceptor acknowledged the holistic and interpersonal needs of the new nurses. Achievement and relationships were high psychosocial needs. Self-actualization was the highest interpersonal need.28 The preceptor recognized the learning needs of the new nurse in the hospital ward.

The other dimension of caring, appreciating the existential-phenomenological force, was the highest mean value of all dimensions in this research. The preceptor provided discussions with the new nurses to identify the environment, strengths, and weaknesses, and strategies for coping with new work demands. This is useful for new nurses who feel anxious and stressed.8,29 Anxiety and stress decrease the new nurse's confidence, which results in a decrease in the new nurse's performance.

The results showed that there was a relationship between self-efficacy and the performance and satisfaction of new nurses. The researchers based their analysis on the social cognitive theory proposed by Albert Bandura that self-efficacy consists of personal confidence and confidence in the abilities and skills possessed to actualize into life.30 Self-efficacy is associated with successful performance.31

New nurses’ self-efficacy is influenced by being given a model from their preceptor. Also, new nurses build confidence by learning from other new nurses.30,31 The new nurse receives a big motivation if the preceptor convinces the new nurse that they can do at least some part of the task.

Individuals with high self-efficacy will demonstrate their commitment and self-motivation for the best performance. Conversely, a person with low self-efficacy will be overwhelmed with doubts about the ability she or he has. The individual faced with difficulties will decrease her or his efforts for reaching the target and can even surrender. This statement supports the opinion of Bandura that self-efficacy is related to motivation with the three needs of McClelland, namely achievement needs, power needs, and the need for affiliation. These three needs were also investigated by Judge et al. in 2007 about the self-efficacy relationship with the performance performed by some staff members. The results of Judge et al. show that self-efficacy is closely related to staff performance.12 Self-efficacy determines the new nurse's readiness to perform tasks in the workplace.

ConclusionThis study showed that there was a significant positive correlation between having a caring preceptor and self-efficacy with job satisfaction and new nurse performance. Both caring preceptor and self-efficacy were significant predictors, accounting for 37.2% of job satisfaction, and were significant predictors for 35.9% of new nurse performance. Nursing managers can take measures to develop caring preceptor and self-efficacy as a strategy to decrease the turnover rate in the hospital. Thus, further studies should be performed to detect the factors influencing the caring preceptor and self-efficacy, and subsequently, take reasonable measures to improve the caring preceptor and self-efficacy.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

This work is supported by Hibah PITTA 2018 funded by DRPM Universitas Indonesia No. 1852/UN2.R3.1/HKP.05.00/2018.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the Second International Nursing Scholar Congress (INSC 2018) of Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia. Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.