To analyse the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of nurses in Spanish out-of-hospital Emergency Services, identifying predictor factors of greater severity.

MethodA multicentre cross-sectional descriptive study was designed, including all nurses working in any Spanish out-of-hospital Emergency Services between 01/02/2021 and 30/04/2021. The main outcomes were the level of depression, anxiety and stress assessed through the DASS-21 scale. Sociodemographic, clinical, and occupational information was also collected. Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to determine possible associations between variables.

ResultsThe sample included 474 nurses. 32.91%, 32.70% and 26.33% of the participants had severe or extremely severe levels of depression, anxiety and stress, respectively. Professionals with fewer competencies to handle stressful situations, those who had used psychotropic drugs and/or psychotherapy on some occasion before the pandemic onset, or those who had changed their working conditions presented more likelihood of developing more severe levels of depression, anxiety and/or stress.

ConclusionNurses in Spanish out-of-hospital Emergency Services have presented medium levels of depression, anxiety and stress during the pandemic. Clinical and occupational factors have been associated with a higher degree of psychological distress. It is necessary to adopt strategies that promote professionals’ self-efficacy and mitigate the triggers of negative emotional states.

Analizar el impacto de la pandemia por COVID-19 sobre la salud mental de las enfermeras de los Servicios de Emergencias extrahospitalarias españoles, identificando factores predictores de una mayor gravedad.

MétodoEstudio descriptivo transversal multicéntrico, cuya población de estudio fueron todas las enfermeras que entre el 01/02/2021 y el 30/04/2021 se encontrasen trabajando en cualquier Servicio de Emergencias extrahospitalarias español. Las variables principales fueron el nivel de depresión, ansiedad y estrés, evaluado mediante la escala DASS-21, recogiéndose también información sociodemográfica, clínica y laboral. Se llevaron a cabo análisis univariantes y multivariantes de regresión logística para determinar posibles asociaciones entre las variables.

ResultadosLa muestra estuvo formada por 474 enfermeras. El 32,91%, el 32,70% y el 26,33% de los participantes presentaron niveles graves o extremadamente graves de depresión, ansiedad y estrés, respectivamente. Los profesionales con menos competencias para manejar situaciones estresantes, los que habían utilizado psicofármacos y/o psicoterapia en alguna ocasión previa al inicio de la pandemia o aquellos a los que se les modificaron sus condiciones laborales presentaron más riesgo de desarrollar niveles más graves de depresión, ansiedad y/o estrés.

ConclusiónLas enfermeras de los Servicios de Emergencias extrahospitalarias españoles han presentado niveles medios de depresión, ansiedad y estrés durante la pandemia. Se han identificado factores clínicos y laborales que se asocian con un mayor grado de afectación psicológica. Es necesario la adopción de estrategias que fomenten la autoeficacia de los profesionales y mitiguen los factores desencadenantes de estados emocionales negativos.

- •

The out-of-hospital emergency services (SEMs for their initials in Spanish) have restructured their organisation and modified their operations to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic.

- •

This study has enabled us to determine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Spanish SEM nurses.

- •

Clinical and employment factors associated with greater psychological impact on Spanish SEM nurses were identified.

- •

The results of this study support the development of interventions aimed at strengthening the mental health and well-being of Spanish SEM nurses.

- •

Psychological support programmes, early identification of risk factors, resilience and self-care training, and the promotion of a support or recognition culture are some examples of these interventions.

Since its emergence COVID-19 has posed significant challenges to both health systems and society. In this context, the Spanish out-of-hospital Emergency Services (SEMs) have had to modify their organisation and operations to a greater or lesser extent, integrating new functions and increasing the portfolio of services offered, so as to be able to respond to the growing number of calls requesting urgent healthcare assistance or simply requiring information related to COVID-19.1,2 Despite this, on some occasions, this increase in demand, together with the limitation of available healthcare resources, has led to the saturation and collapse of Spanish SEMs.2,3

A consequence of these changes is that SEM nurses became one of the main providers of healthcare and care of the population, especially when the person refused to go to the hospital for fear of becoming infected.4 However, this also made them one of the groups with the greatest exposure to the virus and, therefore, with the highest risk of contracting the disease,5 whilst also increasing their vulnerability to the development of psycho-emotional disorders, sleep disturbances, difficulties in interpersonal relationships, and substance abuse behaviours.6,7 Furthermore, nursing practice in SEMs was carried out in direct contact with patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, in small spaces with very limited opportunities for ventilation.7 All of this affected the practice of their professional duties, reducing their capacity for care, understanding and decision-making.8

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the psycho-emotional disorders most frequently developed by nurses were stress, anxiety and depression, as well as post-traumatic stress disorder.8 Stress is defined as an intense or prolonged feeling of psychological discomfort due to exposure to internal or external factors of a traumatic event.9 According to the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, stress is the second most common health problem in the workplace, with exponential growth observed in recent decades.10 During the pandemic, the majority of nurses were exposed to traumatic events not previously experienced, which resulted in high levels of stress, as shown by other authors.7,8 Anxiety is a consequence of a sustained level of stress, which arises when the individual anticipates a future threat that may or may not occur.9 However, during the pandemic, the repetition of unpleasant situations, such as “the feeling of tearing the patient away from their home and family and taking them to the hospital to die,” was constant. Depression is a major emotional disorder, in which the person reports a feeling of fatigue or loss of energy, accompanied by feelings of worthlessness and guilt. It is common that in this situation it is difficult for them to think and make decisions, and it is even accompanied by a recurring death wish. It is, therefore, a serious condition that can endanger the life of those who suffer from it.9

Multiple studies, carried out in other healthcare settings during the COVID-19 pandemic, concluded that nurses are the healthcare professionals most likely to develop these negative effects, because they dedicate a large part of their workday to direct patient care.11–13 However, this is an aspect that has been poorly studied in nurses in the Spanish extra-hospital setting. At this point, it should be taken into account that in other countries where the SEM model is based on the “scoop and run” philosophy, health care is provided by paramedics or technical staff who are guided electronically by hospital staff and transport the patient to the appropriate health centre in the shortest possible time.14 However, the Spanish SEM model is based on the “stay and play” philosophy where healthcare is provided by a multidisciplinary team, comprising doctors, nurses and health emergency technicians who stabilise and treat the patient at the scene of the incident, before transferring them to hospital.15,16 For this reason, the results obtained in the first model are incomparable to those obtained in this research study.17

The objective of this study was therefore to analyse the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Spanish EMS nurses, identifying predictors of greater severity.

MethodDesignDescriptive, cross-sectional, multi-centre.

ParticipantsThe study population was all nurses who, between 02/01/2021 and 04/30/2021, were actively working in any Spanish SEM. The final sample was made up of those professionals who, voluntarily, decided to participate in the study, excluding cases in which the questionnaire was not completed in its entirety.

Sample size estimationTaking into account that the active nurses in the Spanish SEMs in 2020 were 3,508, the minimum number of participants to recruit amounted to 407 in the assumption p = q = 50%, for a confidence interval of 95% and a margin of error of 5%, considering 15% of possible losses.

Sample-data collectionParticipant selection was carried out through non-probabilistic sampling at the discretion of experts. The letter of invitation to the study was distributed by the governing bodies of the SEMs and the Prehospital Emergencies Research Network (RINVEMER-SEMES), through their own communication channels. This letter provided information on the characteristics and objectives of the study, highlighting its voluntary and anonymous nature, and there was no incentive for the participants. In its final part, the link to the open online questionnaire used for data collection was included, located on the e-Encuesta® platform. In this link, an access restriction was established based on the Internet Protocol (IP), so that it could only be used on one occasion and thus avoid multiple responses from the same participant. The questionnaire was not adapted in real time nor were the questions randomised. The time required to complete it was 10–15 minutes.

Variables–measurement toolsDepression, anxiety and stress levels were the main study variables, evaluated using the reduced version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21), created by Lobivond et al.18 and validated in the Spanish population by Bados et al.19 It consists of 3 subscales, with 7 items each, in which the person indicates the frequency with which they have experienced symptoms related to different emotional states in the previous 2 weeks, using a 4-point Likert scale, where 0 corresponds to “never,” and 3 to “always”. The score of each subscale, which ranges between 0 and 42, is obtained by adding the points of each item and multiplying the result by two. Its interpretation takes into account that the higher the score, the worse the mental health of the person. This scale presents adequate psychometric properties, with good discriminant validity in the detection of mental disorders,19 reaching in this study a value in Cronbach’s α coefficient of .95 for the total scale, .89 for the depression subscale, .89 for anxiety and .90 for stress.

Socio-demographic data (sex, age, living with children under 12 years of age or dependent people), clinical data (history of previous use of psychotropic drugs and/or psychotherapy, previous diagnosis of COVID-19, hospitalisation for COVID-19, vaccination against SARS-CoV-2, level of self-efficacy) and occupational data (accumulated incidence (AI) of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in the autonomous community (AC) of work according to records of the Health Authorities,20 previous work experience in SEMs, direct care to patients, modification of working conditions for organisational reasons, adaptation of the workplace for health reasons), using an ad hoc questionnaire, were also collected.

The person’s perception of their ability to adequately handle stressful situations was evaluated using the General Self-Efficacy Scale (G-SES), in its version validated in the Spanish population.21,22 It consists of 0 items, with 10 response options, where 1 corresponds to “strongly disagree or never” and 10 corresponds to “strongly agree or always”. Its score range between 10 and 100, with higher values indicating higher levels of self-efficacy. It presents robust psychometric properties, demostrating high predictive capacity in assessing coping styles, 22 obtaining a Cronbach’s α of .94 in this study.

Purely for analytical purposes, and based on the data declared by the Health Authorities as of February 1, 2021, Spanish geography was divided into 3 regions20: ACs with low AI if ≤4,999 cases (Andalusia, Asturias, Cantabria, Ceuta, Galicia, Balearic Islands, Canary Islands), ACs with medium AI if 5,000–6,999 cases (Castilla La Mancha, Catalonia, Valencian Community, Extremadura, Murcia, Basque Country) and ACs with high AI if ≥7,000 cases (Aragón, Castilla y León, La Rioja, Madrid, Melilla, Navarra).

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were summarised using absolute frequencies (n) and percentages (%), using the mean (m) and standard deviation (SD) in the case of quantitative variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to verify compliance with the normality criteria in the quantitative variables. To compare the levels of depression, anxiety and stress based on socio-demographic, clinical and occupational characteristics, the Student’s t-test for independent samples, the one-way ANOVA or the Pearson correlation were used, depending on the nature of the variables. To identify possible predictors of more severe levels of depression, anxiety and stress, odds ratios (OR) were calculated using different logistic regression models, adjusted for sex and age, in which the variables that obtained statistical significance in the previous univariate analyses were included. To do this, it was necessary to dichotomise the values obtained on the DASS-21 scale into normal-mild-moderate or severe-extremely severe, taking into account the criteria established by Lovibond et al.19 The existence of statistical significance was considered if p < .05. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS software version 28.0 (IBM-Inc., Chicago-IL-USA).

Ethical and legal aspectsThe study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Valladolid-East Health Area (PI20-2052). The principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki were respected at all times, together with the minimum requirements demanded by Spanish and European legislation. This study has adhered to the guidelines for the communication of observational studies collected in the STROBE23 initiative and the results of questionnaires and online surveys collected in the CHERRIES24 Initiative.

The completed return of the questionnaire implied the person’s informed consent to participate in the study. The consent could be revoked at any time, without having to provide any justification. The confidentiality of the participants was maintained at all times, as the e-Encuesta® platform did not provide any sensitive data of the person responding to the questionnaire. No data was used for purposes other than those stated in the consent nor was it transferred to people outside the study.

ResultsThe questionnaire completion rate was 95.37%. The number of nurses who agreed to participate in the study was 474, of which 69.41% (n = 329) were women, with the mean age being 44.03 years (SD ± 9.06). Their average work experience in the extra-hospital setting was 15.42 years (SD ± 9.10), with the majority dedicated to direct patient care tasks (n = 395). 18.35% (n = 87) stated that they had required psychotherapy and/or pharmacological treatment at some point prior to the start of the pandemic. Regarding family responsibilities, half of the participants lived with minors or dependent people in the same home. Around 25% of the nurses worked in regions with low rates of declared COVID-19 cases, with the remaining 75% distributed homogeneously among the ACs with medium or high AI. During the pandemic, 54.64% (n = 259) were forced to modify their working conditions, requiring adaptation of the workplace as a consequence of the new existing epidemiological conditions in 73 cases. Of all the participants, 85 obtained a positive result in the screening tests for the detection of SARS-CoV-2, 9 of them requiring hospitalisation. At the time of completing the questionnaire, around 75% of the sample had received at least one vaccine dose. The mean value of self-efficacy was 70.09 (SD ± 16.00).

With regards to depression, anxiety and stress levels, the average score obtained was 19.37 (SD ± 10.94), 11.64 (SD ± 10.73) and 14.57 (SD ± 10.93), respectively. 32.91% (n = 156), 32.70% (n = 155) and 26.33% (n = 125) presented levels of depression, anxiety and stress categorised as severe or extremely severe.

Professionals whose working conditions were modified (p < .001) or those others who had previously used psychotropic drugs and/or psychotherapy (p < .001) presented with more severe levels of depression (Table 1).

Levels of depression in out-of-hospital nurses based on their socio-demographic, clinical and occupational characteristics.

| Depression | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Man | Woman | |||

| 13.14 ± 11.00 | 15.20 ± 10.86 | .060$ | |||

| Psychotropic/psychotherapy PH | No | Si | |||

| 13.69 ± 1.27 | 18.51 ± 12.86 | <.001$ | |||

| Persons dependent on their care | No | Si | |||

| 14.55 ± 11.29 | 14.61 ± 10.50 | .949$ | |||

| Direct care | No | Si | |||

| 16.03 ± 11.91 | 14.28 ± 10.72 | .231$ | |||

| Change in employment conditions | No | Si | |||

| 12.29 ± 10.17 | 16.47 ± 11.19 | <.001$ | |||

| Job adaptation | No | Si | |||

| 14.51 ± 10.95 | 14.90 ± 10.93 | .780$ | |||

| ACS | Low AI | Medium AI | High AI | ||

| 14.17 ± 10.31 | 14.84 ± 11.12 | 14.57 ± 11.19 | .878# | ||

| Positive COVID-19 diagnosis | No | Si | |||

| 14.44 ± 10.79 | 15.20 ± 11.61 | .580$ | |||

| Hospitalisation due to COVID-19 | No | Si | |||

| 14.44 ± 10.86 | 21.56 ± 13.03 | .141$ | |||

| SARS-CoV-2 vaccination | No | Si | |||

| 14.92 ± 12.08 | 14.46 ± 10.56 | .715$ | |||

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. $t Student for independent samples; #One-factor ANOVA.

Abbreviations: ACs: Autonomous Communities; AI: accumulated incidence; PH: Personal history.

The factors related to higher anxiety levels were being female (p = .010), previous use of psychotropic drugs and/or psychotherapy (p < .001), not directly caring for patients (p = .028) and change in working conditions (p < .001) (Table 2).

Levels of anxiety in out-of-hospital nurses based on their socio-demographic. clinical and occupational characteristics.

| Anxiety | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Man | Woman | |||

| 9.75 ± 10.49 | 12.47 ± 10.75 | .010$ | |||

| Psychotropic/psychotherapy PH | No | Yes | |||

| 10.33 ± 9.54 | 17.47 ± 13.53 | <.001$ | |||

| Persons dependent on their care | No | Yes | |||

| 10.87 ± 10.02 | 12.61 ± 11.52 | .080$ | |||

| Direct care | No | Yes | |||

| 14.23 ± 11.42 | 11.12 ± 10.53 | .028$ | |||

| Change in employment conditions | No | Yes | |||

| 9.01 ± 9.24 | 13.88 ± 11.39 | <.001$ | |||

| Job adaptation | No | Yes | |||

| 11.43 ± 10.71 | 12.79 ± 10.84 | .325$ | |||

| ACS | Low AI | Medium AI | High AI | ||

| 11.07 ± 9.44 | 12.46 ± 10.97 | 11.17 ± 11.27 | .421# | ||

| Positive COVID-19 diagnosis | No | Yes | |||

| 11.43 ± 10.70 | 12.61 ± 10.89 | .365$ | |||

| Hospitalisation due to COVID-19 | No | Yes | |||

| 11.54 ± 10.62 | 16.89 ± 15.17 | .139$ | |||

| SARS-CoV-2 vaccination | No | Yes | |||

| 12.28 ± 11.56 | 11.44 ± 10.46 | .488$ | |||

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. $t Student for independent samples; #One-factor ANOVA.

Abbreviations: ACs: Autonomous Communities; AI: accumulated incidence; PH: Personal history.

More serious levels of stress were observed in women (p = .023), in professionals who did not have direct contact with patients (p = .031), in those whose working conditions had been modified (p < .001) or in the participants who had previously required psychotropic drugs and/or psychotherapy (p < .001) (Table 3).

Levels of stress in out-of-hospital nurses based on their socio-demographic, clinical and occupational characteristics.

| Stress | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Man | Woman | |||

| 17.63 ± 11.14 | 20.13 ± 10.78 | .023$ | |||

| Psychotropic/psychotherapy PH | No | Yes | |||

| 18.28 ± 10.49 | 24.18 ± 11.64 | <.001$ | |||

| Persons dependent on their care | No | Yes | |||

| 18.68 ± 10.92 | 20.23 ± 10.92 | .126$ | |||

| Direct care | No | Yes | |||

| 21.90 ± 11.40 | 18.86 ± 10.79 | .031$ | |||

| Change in employment conditions | No | Yes | |||

| 16.89 ± 10.52 | 21.42 ± 10.87 | <.001$ | |||

| Job adaptation | No | Yes | |||

| 19.21 ± 11.07 | 20.22 ± 10.22 | .446$ | |||

| ACS | Low AI | Medium AI | High AI | ||

| 18.59 ± 10.24 | 20.06 ± 10.03 | 19.17 ± 11.30 | .506# | ||

| Positive COVID-19 diagnosis | No | Yes | |||

| 19.17 ± 11.03 | 20.26 ± 10.54 | .395$ | |||

| Hospitalisation due to COVID-19 | No | Yes | |||

| 19.29 ± 10.91 | 23.56 ± 12.48 | .337$ | |||

| SARS-CoV-2 vaccination | No | Yes | |||

| 19.81 ± 11.67 | 19.23 ± 10.71 | .635$ | |||

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. $t Student for independent samples; #One-factor ANOVA.

Abbreviations: ACs: Autonomous Communities; AI: accumulated incidence; PH: Personal history.

Self-efficacy, age and previous work experience in the extra-hospital setting were negatively and weakly related to the levels of depression, anxiety and stress of the participating nurses (Table 4).

Relationship between the levels of stress, anxiety and depression of out-of-hospital nurses and their level of self-efficacy, age and previous work experience.

| Stress | Anxiety | Depression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | Pearson’s R | −.337 | −.310 | −.379 |

| p-value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Age | Pearson’s R | −.156 | −.106 | −.134 |

| p-value | <.001 | .021 | .004 | |

| Work experience in SEM | Pearson’s R | −.143 | −.118 | −.113 |

| p-value | .002 | .010 | .014 |

Abbreviations: SEM: Out-of-hospital emergency service.

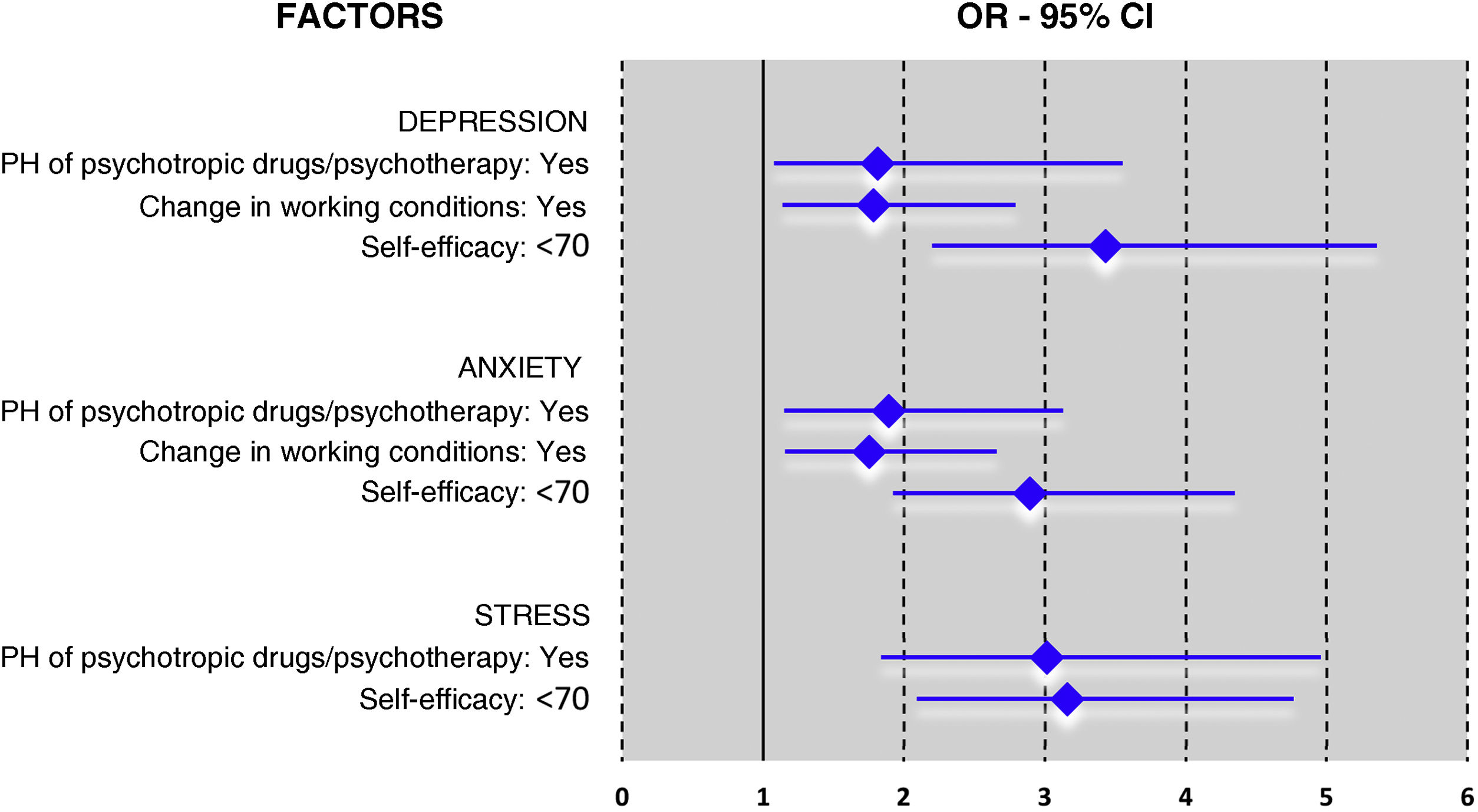

Previous consumption of psychotropic drugs and/or psychotherapy increased the probability of developing more severe levels of depression (OR 1.811; 95% CI 1.076–3.049; p = .025), anxiety (OR 1.892; 95% CI 1.145–3.125; p = .013) or stress (OR 3.015; 95% CI 1.834–4.957; likewise, reporting less self-efficacy favoured the appearance of more severe symptoms of depression (OR 3.428; 95% CI 2.196–5.353; p < .001), anxiety (OR 2.890; 95% CI 1.921–4.348; p < .001) and stress (OR 3.157 ; 95% CI 2.091–4.766; Having undergone changes in working conditions was related to a greater risk of presenting high levels of depression (OR 1.781; 95% CI 1.136–2.792; p = .012) and anxiety (OR 1.751; 95% CI 1.155–2.655; p = .008) (Fig. 1).

Logistic regression model of predictive factors of severe or extremely severe levels of depression, anxiety and stress in nurses in the out-of-hospital setting.

An OR value >1 indicates a positive association with severe or extremely severe levels of depression, anxiety and stress. All analyses were controlled by sex and age.

Abbreviations: OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; PH: Personal history.

This study analysed the impact of socio-demographic, clinical and occupational factors on the mental health of Spanish SEM nurses during the pandemic. Professionals with fewer skills to manage stressful situations, those who had previously used psychotropic drugs and/or psychotherapy, and those whose working conditions were modified were more affected psychologically.

The findings of this study show that one in three nurses presented pathological levels of depression, anxiety and stress, a figure higher than that reported in other healthcare settings.11–13 When comparing this figure with that obtained by other SEM professionals, it was observed that technical personnel were the group most affected by the pandemic, as a result of their poorer working conditions.7

Nurses with less self-efficacy had greater trouble adapting to the reality of the pandemic and were at greater risk of developing severe symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress, a conclusion similar to that obtained by Varghese.25 Sex, age, level of education, work experience and social support are factors that in other studies have been related to the modification of professionals’ perceptions.13 Unlike what was observed in other healthcare settings,13,26 the level of self-efficacy achieved in this study was moderate-high. A possible explanation for this difference is the fact that teamwork was a basic principle of action of the SEM, guaranteeing a proper flow of information and an opportunity for improvement based on training and mutual support.26 In their daily lives, these professionals faced unexpected and challenging situations, where they had to act quickly and efficiently. Continuous adaptation to these changing situations encouraged the development of skills and competencies that allowed the person to achieve higher levels of self-confidence and improve their ability to cope with new adverse situations.27 During the pandemic, therefore, most nurses focused on what they had to do, without thinking or reflecting on their emotions, promoting and reinforcing positive and optimistic attitudes, and avoiding negative feelings such as pain, helplessness or guilt.28

Similarly to that concluded by other authors,29 this study demonstrates that previous consumption of psychotropic drugs and/or psychotherapy was associated with more intense negative psycho-emotional responses. Around 20% of SEM nurses were already using these treatments before the start of the pandemic, a percentage similar to that obtained in other studies, but higher than the 10.7% of the Spanish population.29,30 Furthermore, this consumption increased significantly during this health crisis, as a consequence of continuous exposure to stressful situations, high workload, fear of becoming infected or transmitting the disease, lack of institutional and/or social support, scarcity of material and/or human resources and excess/deficit of information received.31 Having a previous diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder was considered a predisposing factor for the development, persistence or recurrence of new comorbidities, including other mental illnesses.30 This greater susceptibility is a consequence of the person’s worse psycho-emotional situation, which distances them from their comfort zone and requires a capacity for continuous adaptation,30 with work experiences having less influence.32 The under-diagnosis of this type of problem among the healthcare community is an aspect worth highlighting, as it increases the risk of sequelae and chronicities in the medium-long term.31 Preventive programmes and early detection of mental disorders, as well as support measures, should be aimed at those professionals whose vulnerability is greater.33

The change in working conditions increased the nurses’ vulnerability to anxiety-depressive disorders. The SEMs reorganised their resources and operations to respond to the epidemiological situation existing at each moment in time.1,3 To this end, they created specific care and transfer units for patients with suspected symptoms or confirmed cases, making it necessary to relocate nurses for their implementation, with the consequent modification of their working conditions.2,25 Furthermore, the growing number of infected professionals, together with the need to quarantine after contact with a possible case, made it difficult to cover shifts, forcing colleagues to work extra hours.28 The adaptation of displaced professionals to the new context, which was constantly changing, and in which they often had to perform tasks they had not been prepared for, increased the mental burden.34 Non-recognition of the important role that occupational organisational factors played in the physical and mental health of workers could have led to unfairly blaming symptomatic people for not showing resilience.35 To avoid this, at a general level, healthy work environments must be promoted, safety culture improved and broader changes in health policies implemented. At a more specific level, the voluntary relocation of the professional should be prioritised; they should be informed of their new working conditions and trained in any necessary skills.35

Other factors such as sex, age, work experience or type of care were also related to levels of depression, anxiety and/or stress, results similar to those observed in other healthcare settings.7,8,31 However, this relationship disappeared when its effect was analysed jointly with other variables. Difficulties in reconciling personal and family life, assuming the role of primary caregiver, together with their greater empathic capacity are factors that impacted the appearance and resistance of these symptoms in women.36 Older professionals or those with more work experience had greater psychological resistance, as they were more competent in acting in complex unforeseen situations through teamwork and assuming leadership roles.37 Contrary to what might have been expected,7,31 nurses in direct contact with patients were less susceptible to the development of these symptoms. The greater information received about the pandemic process and the feeling of being in control of the situation made these professionals perceive their actions as a continuity of what they usually practised, albeit with higher safety levels.38

This study demonstrates that Spanish SEM nursing staff presented with psycho-emotional problems after the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, despite their high levels of self-efficacy. This result highlights the need to train these professionals in effective coping strategies to avoid impairment in their mental health in the face of future traumatic events. Likewise, early detection of these problems is required, to which an immediate response must be given to avoid chronicity. Specialised support is essential during traumatic situations to restore positivity after negative experiences. The creation of psychological support units within the SEMs, psychiatric teleconsultation, or social support networks are therefore effective measures that help the person reflect on their psycho-emotional reactions to adverse events.39 Its implementation must be encouraged by healthcare organisations, so that professionals learn to manage their levels of stress and anxiety; reduce exhaustion; improve their feelings of self-efficacy and self-confidence; increase their resilience, and strengthen their cognitive and emotional skills, based on a comprehensive, multidisciplinary and individualised approach.39

The interpretation of these results should take into account the following limitations. The cross-sectional design did not allow controlling the time factor or establishing causal relationships between variables. Non-probabilistic sampling can induce greater participation of professionals who are more sensitive to the topic or others who are more affected, but having established solid inclusion and exclusion criteria allows us to have greater confidence in the results obtained; even so, the study’s generalisation to other contexts is limited as it is not a random sample. Collecting data through self-administered questionnaires can facilitate the appearance of systematic response bias, related to social desirability or the tendency to choose extreme options. This bias is acceptable in this type of studies, and must be taken into account. Providing information regarding data confidentiality reduces responses based on social desirability, but not extreme values, which in this research were the most common. Its strengths include its multicentre nature, the representativeness of the sample of all Spanish SEMs and the use of validated questionnaires with excellent psychometric properties.

To conclude, Spanish SEM nurses presented average levels of depression, anxiety and stress during the pandemic. We identified clinical and occupational factors that were associated with a higher degree of psychological involvement. Strategies need to be adopted to promote the self-efficacy of professionals and mitigate the triggers of negative emotional states, especially aimed at professionals with previous mental pathologies.

FundingThis study was funded by the ASISA Foundation (Spain). The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official opinions of the funding body.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to express our gratitude to the nurses participating in the study, as well as to the governing bodies of the different Spanish out-of-hospital Emergency Services and to the Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine (SEMES) who facilitated the survey distribution.

María Elena Castejón-de-la-Encina, Fernando de-Miguel-Saldaña, Patricia Fernán-Pérez, José Julio Jiménez-Alegre, Rafael Martín-Sánchez, Carmen María Martínez-Caballero, María Molina-Oliva, Almudena Morales-Sánchez, José M. Navalpotro-Pascual, Elena Pastor-Benito, Carlos Eduardo Polo-Portes, Ana María Requés-Marugán, Leticia Sánchez-del-Río, Israel John Thuissard.