To determine the impact of advanced practice nurses in chronic wound care in the adequacy of treatments for patients with chronic wounds and the consumption of dressings in the districts where they have been implemented.

MethodA quasi-experimental pre-poststudy without a control group with 3 measurements: pre-implementation in 2015, one year after implementation in 2016, and 2years post-implementation in 2017, in the health districts (HD) where the role of the advanced practice nurse in chronic wound care was piloted in Andalusia. The main variables were trained professionals, consultancies, prevalence of chronic wounds, adequacy of treatments and economic cost in materials for the participating HD.

ResultsThe training of a total of 2717 health teams with a total of 95,095 teaching hours was achieved. In addition, a total of 3871 consultancies were performed. The prevalence of patients with injuries in the home care (HC) programme and in care homes diminished significantly, to almost half. The adequacy of the treatments increased to 90% and savings of more than 250,000€ in dressings were achieved in just 2 years.

ConclusionThe prevalence of chronic wounds during the 2 years of implementation decreased by almost half. Adequacy of training and consultancy was achieved, rationalising health expenditure and ensuring efficient care for patients with chronic wounds.

Determinar el impacto de las enfermeras de práctica avanzada en heridas crónicas complejas (EPA-HCC) en la adecuación de los tratamientos de los pacientes con heridas crónicas y el consumo de apósitos en los distritos donde están implantadas.

MétodoEstudio de tipo cuasiexperimental de tipo pre-post sin grupo control con 3mediciones: preimplantación en 2015, al año de implantación en 2016 y a los 2años postimplantación en 2017, en los distritos sanitarios donde se estaba pilotando la EPA-HCC en Andalucía. Las variables principales son: número de profesionales formados, número de consultorías, prevalencia de heridas crónicas, adecuación de los tratamientos y coste económico en materiales para cura de los DS participantes.

ResultadosSe ha conseguido la formación de un total de 2.717 profesionales sanitarios con un total de 95.095 h lectivas; además, se han realizado un total de 3.871 consultorías y asesorías. La prevalencia de pacientes con lesiones en programa de atención domiciliaria y en residencias ha disminuido a la mitad. La adecuación de los tratamientos ha aumentado hasta el 90% y se ha conseguido un ahorro de más de 250.000 € en apósitos, en un período de 2años.

ConclusiónLa prevalencia de heridas crónicas durante los 2años de implantación ha disminuido a la mitad, se ha conseguido una correcta adecuación del plan de formación y consultoría, consiguiendo racionalizar el gasto sanitario y una eficiente atención a las personas con heridas crónicas.

Chronic complex wounds are a primary level health problem, with serious repercussions for the people affected by them, the care environment and the healthcare systems. Approaching them requires an integrated care system whereby the complete course of the disease is taken into account for greater effectiveness. In Spain, up until now, there have been few organisational models advancing towards the integration of care devices to promote the efficient use of resources, improved satisfaction and a better quality of life for the chronic wound patient.

What does this article contribute?The incorporation of the advanced practice nurses as a model of intersectorial, comprehensive and integrated model in chronic complex wound care in the health system has almost halved chronic wound prevalence in the health districts where they have been introduced. They have achieved correct adaptation of the training and consultancy plan with a rationalisation of healthcare costs and efficient attention to people with chronic wounds.

Chronic complex wounds (CCW) are a problem in the healthcare area, often invisible and underestimated, which up until now has impeded progression on knowledge, detection and detention of them.1

However, as a primary level health problem they have serious repercussions on different levels, both for the patients (on the health status of those who suffer from them and in their quality of life), the care environment and the health systems, where high costs are levied.

Chronic wounds could be defined as skin injuries with a low or no tendency to heal, whilst the cause of them continues.2

Despite greater knowledge and the development of ever-increasingly sophisticated interventions, many clinicians face the daily challenge of wounds which are “difficult to heal”,3 for which great efforts and intentions are made, yet the healing is prolonged over time or fails and this lead to an increase in psychosocial stress and anxiety for those who have been involved in the intervention. A major financial burden ensues,4–7 and for these reasons a new form of approach is required.

According to current knowledge, CCW control requires the development of intersectorial, integral and integrated interventions for the greatest possible effectiveness. Thus, to the traditional measures of public health in early prevention and detection of this entity are added key elements such as a global strategy for combating the presentation of CCW, diagnosis and treatment, follow-up, psychosocial and rehabilitating aspects. This in turn requires an improvement in clinical organisation and coordination of healthcare levels, putting into perspective the diverse spectrum upon which action is required, including the natural history of the CCW on the one hand and the healthcare system organisation on the other.

CCW therefore require an integrated care system, so that the complete evolution of the process is considered. It is essential that new organizational models be implemented so that advancement can be made toward integration of care devices, the efficient use of resources, greater satisfaction and a better user quality of life.8

Several advanced practice figures of renowned prestige have been described internationally in the wound care setting. In the North American context the wound, ostomy and continence [WOC] specialty nursing has been described.9–16 This figure derives from the evolution of an advanced competence which evolved since the 1960s by gastroenterology and urology specialist nurses in the management of stomas.17,18 From the 1980s onward, this began to be a specific specialty, and extended the field of action to chronic wounds. This renowned figure now acts with broad autonomy.

During the decade of the 1990s in the United Kingdom the figure of the tissue viability nurse19–26 was developed. The term “tissue viability” is often misinterpreted and literally refers to the preservation of healthy tissues. It is a very broad term which, when used correctly, refers to tissue damage prevention and management which may include acute and chronic wounds. We could therefore say that despite the name, these nurses specialise in wounds and their situation is similar to their North American counterparts with regard to legal development and financial recognition of their responsibilities.

In Andalusia, due to the difficulty in recognising the specialist figure, a more flexible model was chosen and we understand that this model is better adapted to our context – that of the advanced practice nurse (APN).

The International Council of Nurses defines the APN as “a registered nurse who has acquired expert knowledge, the skills for complex decision-making and the clinical competences for extending their practice, the characteristics of which are determined by the context or country in which they have been licensed to practice”.27

It has become evident that the figure of the CCW APN performs in a complex and dynamic setting, facing continuous and major challenges in offering CCW care. This requires consideration of the complete process that must be effective, good quality and sustainable. The development of new organisational models is required so that we may advance toward the integration of the care devices, promoting efficient use of resources and greater user satisfaction. New interventions in the different public health system levels in Andalusia need to be developed to ensure their optimum coordination.

The APN will help to optimise available resources throughout the entire process. He or she must provide efficient care management, prevention, diagnosis and treatment regardless of the care and social context of the people with CCW. Their mission must also be to manage and coordinate teaching and research activities in CCW care materials.

CCW-APNs have been created with the idea of improving the quality of care and the safety of patients with CCW. The following attributes are applied to them8:

- –

Leaders who guarantee the right to healthcare with all technical and human resources the patient requires, depending on the resources of the centre.

- –

Consultants who make care efficient for people with CW.

- –

People in charge of optimising resources.

- –

Coordinators of research and teaching activities in CW materials.

One of the basic functions they therefore have to perform and which involves the before-mentioned attributes, is the transference of knowledge all professionals possess for the improvement of care quality and safety of particularly complex patients with:

- –

Chronic wounds which are particularly slow to heal.

- –

Where there is no opportunity to undertake certain nursing procedures in their care context.

- –

Where there are doubts about the criteria or guideline to be followed.

- –

Or any other situation which the professionals considers but which justifies consultation with the APN in CW.

To transfer knowledge the CCW-APN use different strategies including mainly teaching and consultancy. But does this task have an impact on clinical practice? Is knowledge transferred from the CCW-APN to the clinical nurses and from them to the patients?

Due to all of the above we are putting forward the following objectives to:

- –

Determine the impact of the APN in the adequacy of chronic wound care treatment in the districts where they work.

- –

Analyse the results on the consumption of dressings in these health districts (HD).

This articles forms part of a wider project intended to measure the overall work of some of the aspects (prevention, treatment, type of wounds, etc.) of the CCW-APN.

A quasiexperimental type of pre-post test was undertaken with no control group, with 3 measurements: pre-implantation in 2015, a one year post-implantation in 2016 and a two-year post-implantation in 2017, in the HD where the CCW-APN was being piloted in Andalusia: HD Poniente (HDP), HD Jaén-Norte (HDJN), HD Serranía de Ronda (HDSR).

The population comprised all nurses of the HD and nursing homes (public or private) where the figure of the CCW-APN was being piloted.

All professionals who had had or could have had patients with CCW in their care were included in their respective basic health areas. These professionals had completed training in CCW in the before-mentioned HD (HDP, HDJN and HDSR).

Specialist nurses (maternal and child health or mental health), case management nurses and senior management nurses were excluded because they did not have patients with chronic wounds in their care.

The type of sample selected was an accidental or convenience sample from the nurses who participated in data collection in the 3 cut-off points of prevalence between October and November 2015, 2016 and 2017.

This was a conceptual sample, due to the proposed inclusion criteria and all nurses trained during the analysis period were therefore included.

With regard to intervention, after their introduction the CCW-APN was performing a programmed and regulated job until 2017, when basic, necessary and obligatory courses were established:

- –

Course on the prevention of dependence-related injuries (DRI).

- –

Course on review of DRI treatment.

- –

Course on the care of people with lower extremity injuries.

- –

Course on the strategy of care and review of bacterial load management.

- –

Course on review and management of burns.

This training was organised based around the main demands of the professional. This was gathered from previous analysis regarding their expectations, needs, and doubts regarding their programming.

The intention here was to determine whether the training and review of knowledge have an impact and significantly improve the adequacy of the treatments in line with recommendations of clinical practice guidelines (CPG).

A telephone consultancy service was also made available for all the doubts the nurses could have had regarding the management and treatment of CCW after receiving training.

As previously mentioned, this project forms part of a broader study, the aim of which is to measure the APN work in CCW at several levels. In this study, variables are presented which are related to treatment adequacy. Information on the following variables was collected:

- –

Hours of training imparted by the APNs.

- –

Percentage of trained professionals.

- –

Number of consultations made.

- –

Population in home care programme (HCP).

- –

Rate of response from professionals.

- –

Number of people with a chronic wound.

- –

Type of treatment used in chronic wounds, both for filling and dressing the wound depending on its status.

- –

Adequacy of the treatment to the standards recommended by the CPG (specifically the Guide of the Andalusia Health Service and of the EPUAP-NPUAP guides were used). This was classified into: adequate when it fitted in with the CPG, and inadequate when the CPG recommended a more appropriate treatment, but this treatment could be valid and incorrect when the treatment was not in keeping with that indicated in the normal practice standards.

- –

Cost in materials for healing in the participant HD, measured in euros.

This study did not include patients who had been directly attended by the CCW-APN, only those attended by the clinical nurses who had received training and who had been also able to use the consultancy as an additional activity.

The members comprising the CCW-APN in Andalusia, together with their coordinator, carried out prior analysis of the variables to be analysed and which outcomes would be appropriate for each type of care and patient setting. Once the ad hoc documents had been created, for data collection, it was presented in clinical sessions of the different Clinical Management Units of the nursing districts and also in the public and private nursing homes. The documents and questionnaires were created (paper and computer formats) for data collection and these were collected up to completion.

After this, as already mentioned, the projected was put forward with 3 consecutive measurements.

Phase 1. Analysis of the pre-implantation situation of the CCW-APN in Andalusia (2015):

- –

Presentation, exposure and explanation of the ad hoc questionnaire with the variables to be analysed (for the whole Project), for data collection to professionals who were working at that time in different units where the CCW-APN (HDP, HDJN and HDSR) were being piloted, simultaneously with the professionals from the nursing homes.

- –

A powerpoint presentation was made for the professionals involved. They were given the questionnaire in paper and electronic format. They were also presented with a report of analysed results and the start-up of the strategies to develop, intended to respond to the health problems of the existing population.

Phase 2. Analysis after establishment of the CCW-APN after one year (2016):

- –

This analysis provided us with information on the short-term effect of the CCW-APN. Again all the pre-implantation variables were assessed, which led to a comparison being made

- –

All the pre-implantation variables were analysed and assessed again, which enabled a comparison of the results obtained to be made with the initial data.

Phase 3. Evaluation after 2 years (2017):

- –

New collection by the same system of the same variables, which provided us with information of the CCW-APN effect from mid to long term. A final measurement was taken whereby the results obtained were compared with the pre-implantation phase, and a second measurement using the entire variables used. In each work unit both the professionals and patients could vary and not be the same.

The data on the costs of materials from the districts were provided by the Care Strategy. An annual analysis was made of the same by district and hospital from the implantation of the nursing prescription in Andalusia, which has provided a view of costs since 2009.

A descriptive analysis was made of each variable in the study and the frequency measurements and percentages were calculated for the qualitative variables and central tendency measurements and dispersion measurements for the quantitative variables. For analysis the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences programme was used, in its 21.0 version. In all cases the level of significance was considered to be 95%.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the main committee Almeria Centre.

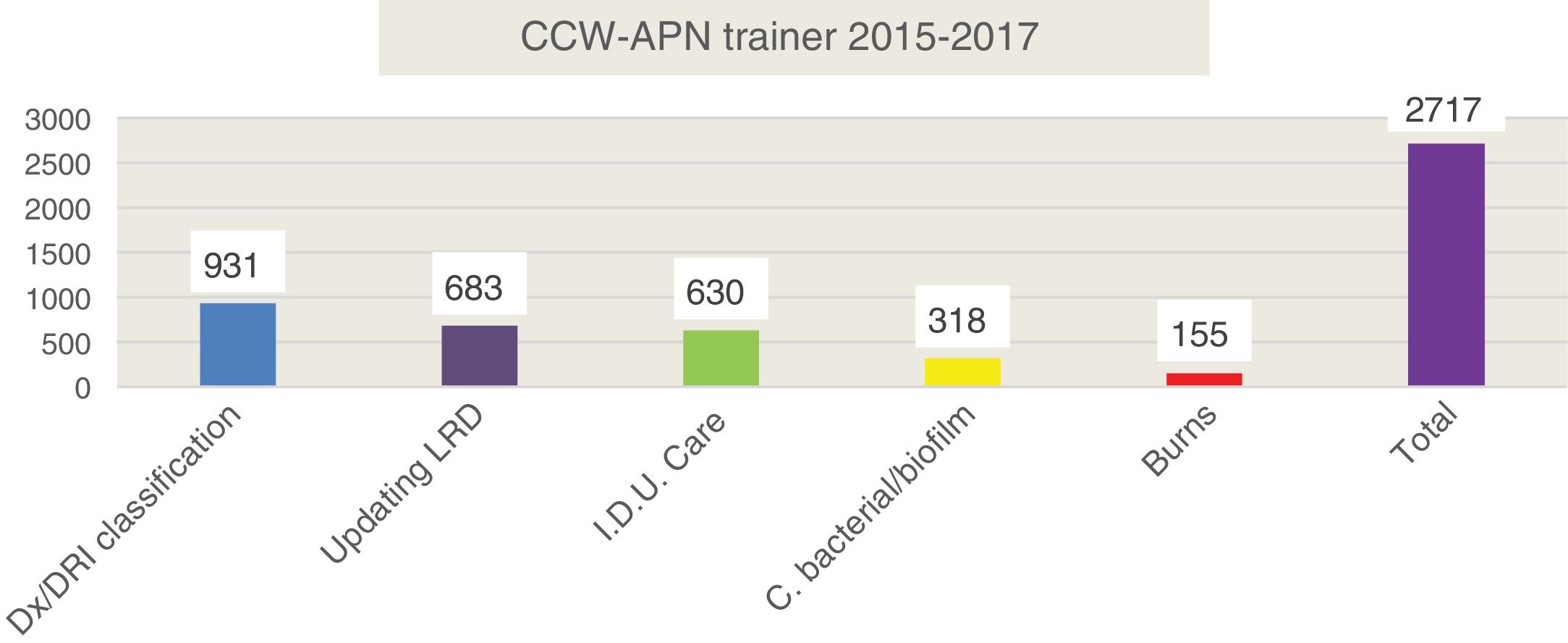

ResultsDuring the CCW-APN's 2 years of functioning the number of trained professionals was almost 3000. We would like to highlight that the training was based on the main demands of the professionals, from prior analysis regarding their expectations, needs and doubts about their programming. The detailed data are shown in Fig. 1.

The majority of trained professionals are nurses and practically all of the nurses of the participant HD were trained in all of the courses which took place. Nursing auxiliaries and physiotherapists were also trained. There was a total of 24,943 class hours, measuring increase of knowledge in all the professionals. The mean of them all and of all the courses was 35%. Another fact to highlight was the level of knowledge gained which the nurses attached to themselves 2 years after starting up the CCW-APN. This rose from 5.9 out of 10 in 2015 to 7.7 out of 10 in 2017, almost 2 points of improvement.

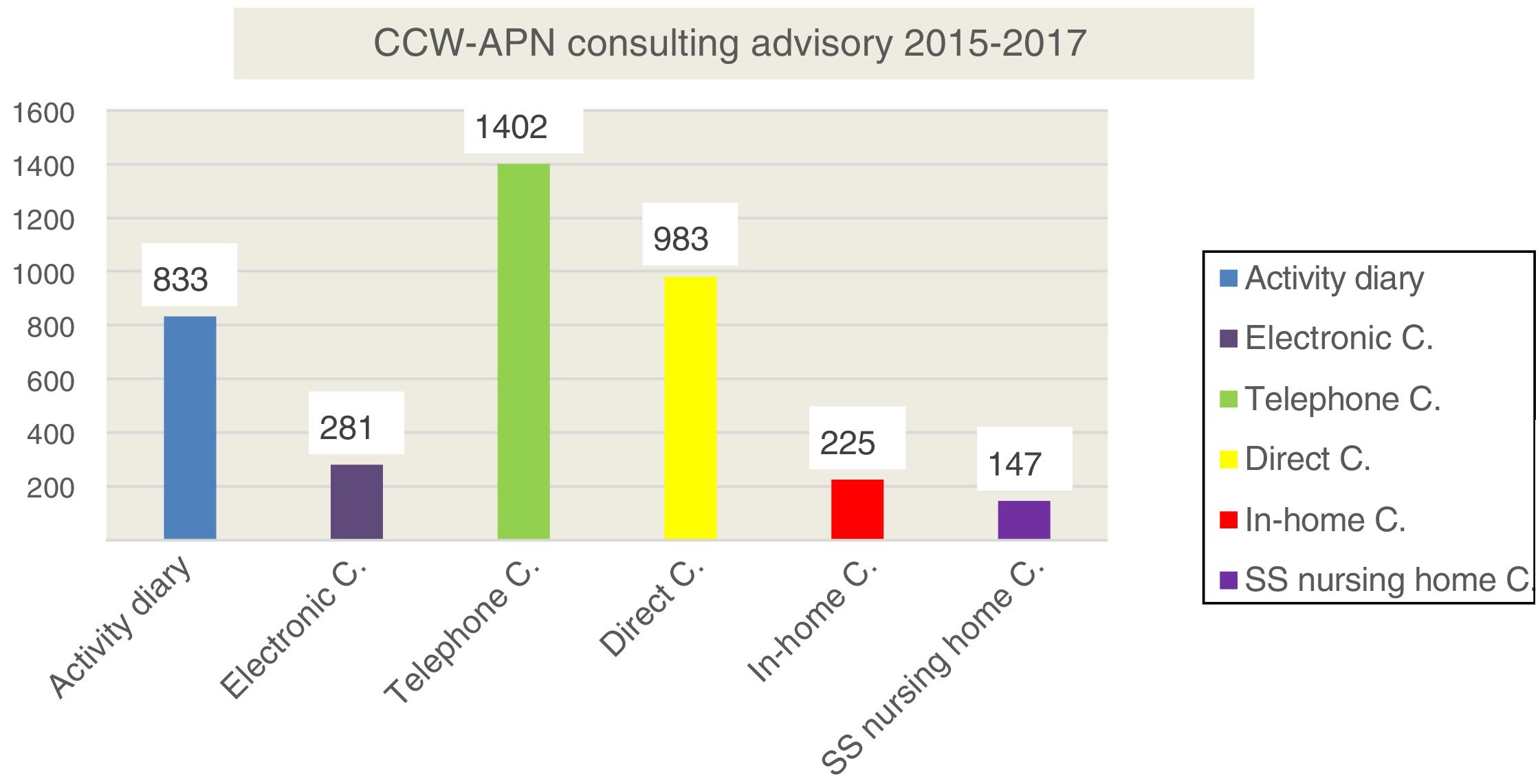

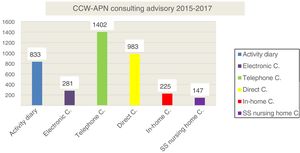

The number of consultations made was 3871, in both primary care and nursing homes, which is contained in Fig. 2, and most of them were over the phone.

After analysis of training and consultation, we went on to analyse the impact of this on healthcare outcomes.

During the 3 cut-off points of prevalence which took place in 2015, 2016 and 2017 the participant HD attended to 715,000 people (approximately 9% of the population in Andalusia). The population of Andalusia increased by 30,000 inhabitants during this period.

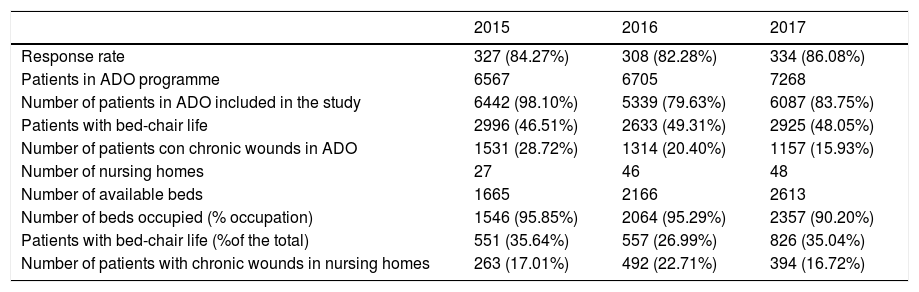

Table 1 presents the response rate data of the professionals, the number and profile of the patients on the ADO programme and the care given in the nursing homes.

Profile of patients in home care programme and nursing homes included in the study.

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response rate | 327 (84.27%) | 308 (82.28%) | 334 (86.08%) |

| Patients in ADO programme | 6567 | 6705 | 7268 |

| Number of patients in ADO included in the study | 6442 (98.10%) | 5339 (79.63%) | 6087 (83.75%) |

| Patients with bed-chair life | 2996 (46.51%) | 2633 (49.31%) | 2925 (48.05%) |

| Number of patients con chronic wounds in ADO | 1531 (28.72%) | 1314 (20.40%) | 1157 (15.93%) |

| Number of nursing homes | 27 | 46 | 48 |

| Number of available beds | 1665 | 2166 | 2613 |

| Number of beds occupied (% occupation) | 1546 (95.85%) | 2064 (95.29%) | 2357 (90.20%) |

| Patients with bed-chair life (%of the total) | 551 (35.64%) | 557 (26.99%) | 826 (35.04%) |

| Number of patients with chronic wounds in nursing homes | 263 (17.01%) | 492 (22.71%) | 394 (16.72%) |

As we may observe, over the 3 years over 300 nurses participated in the study, a response rate of over 80%. There was an increase in over 700 patties in ADO programmes, totalling 7000 from whom data was obtained in 4 out of every 5. Practically half of the patients live their lives from the bed to chair. As we may observe in the same table, the prevalence of patients with injuries in the ADO programme decreased by almost half in these 3 cut-off points.

Regarding the nursing homes, their increase throughout the period was notable. There were reticences during the first year, but these were later resolved when the work of the CCW-APN was appreciated and practically all the public or private centres participated. Data was obtained from almost 2500 residents during the last year, 1000 more than the first year and the rate of occupation was always higher than 90%. One out of every 3 patients had a bed to chair existence.

With regard to the number of injuries in institutionalised patients in homes, although this also decreased, figures are very uneven.

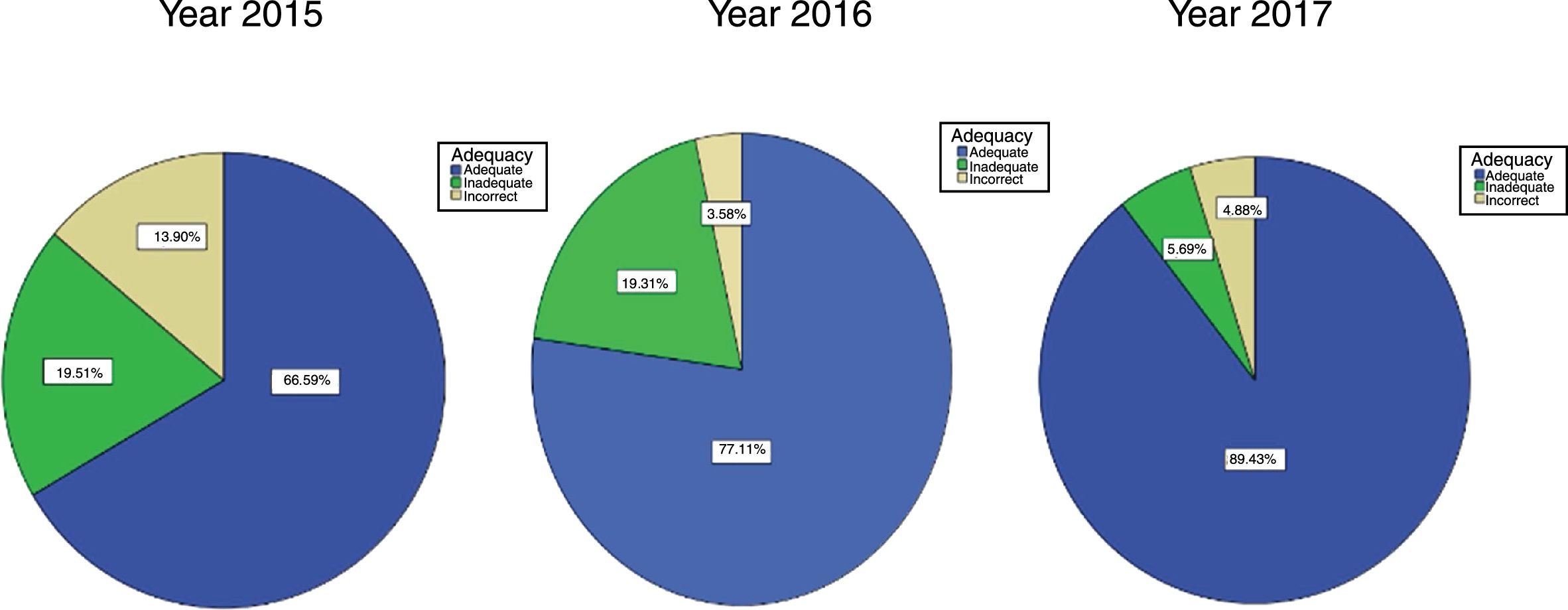

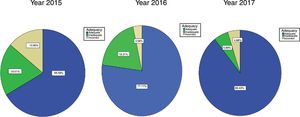

The results of treatment adequacy are presented in Fig. 3.

The striking point about this graph is the increase in the percentage change to the CPG of treatment applied by family nurses, which was 2/3 prior to its implantation and increased to 4/5 after 2 years, significantly reducing not just inappropriate treatments but above all, incorrect ones; these dropped to approximately 4% when in the first year they were around 14%.

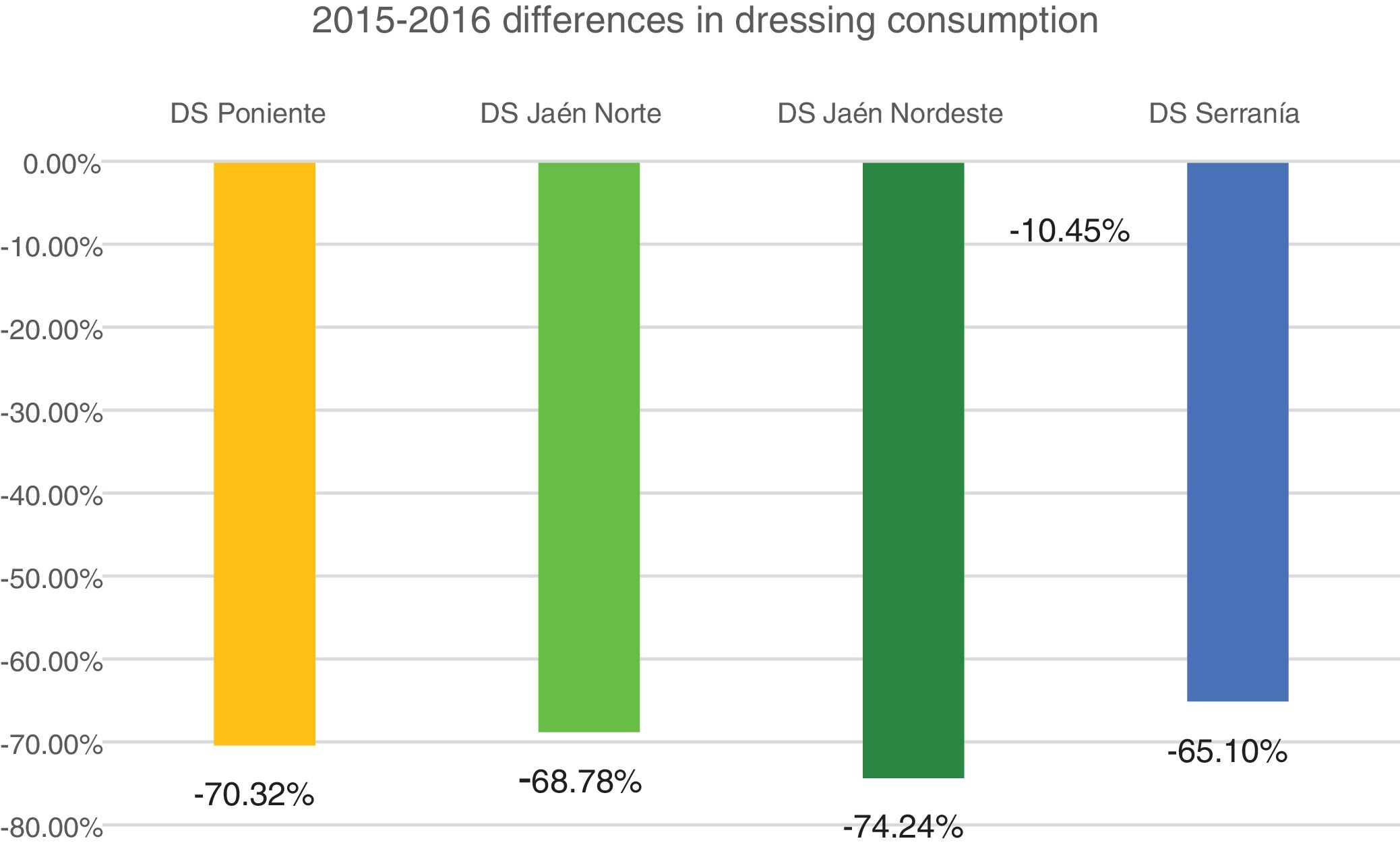

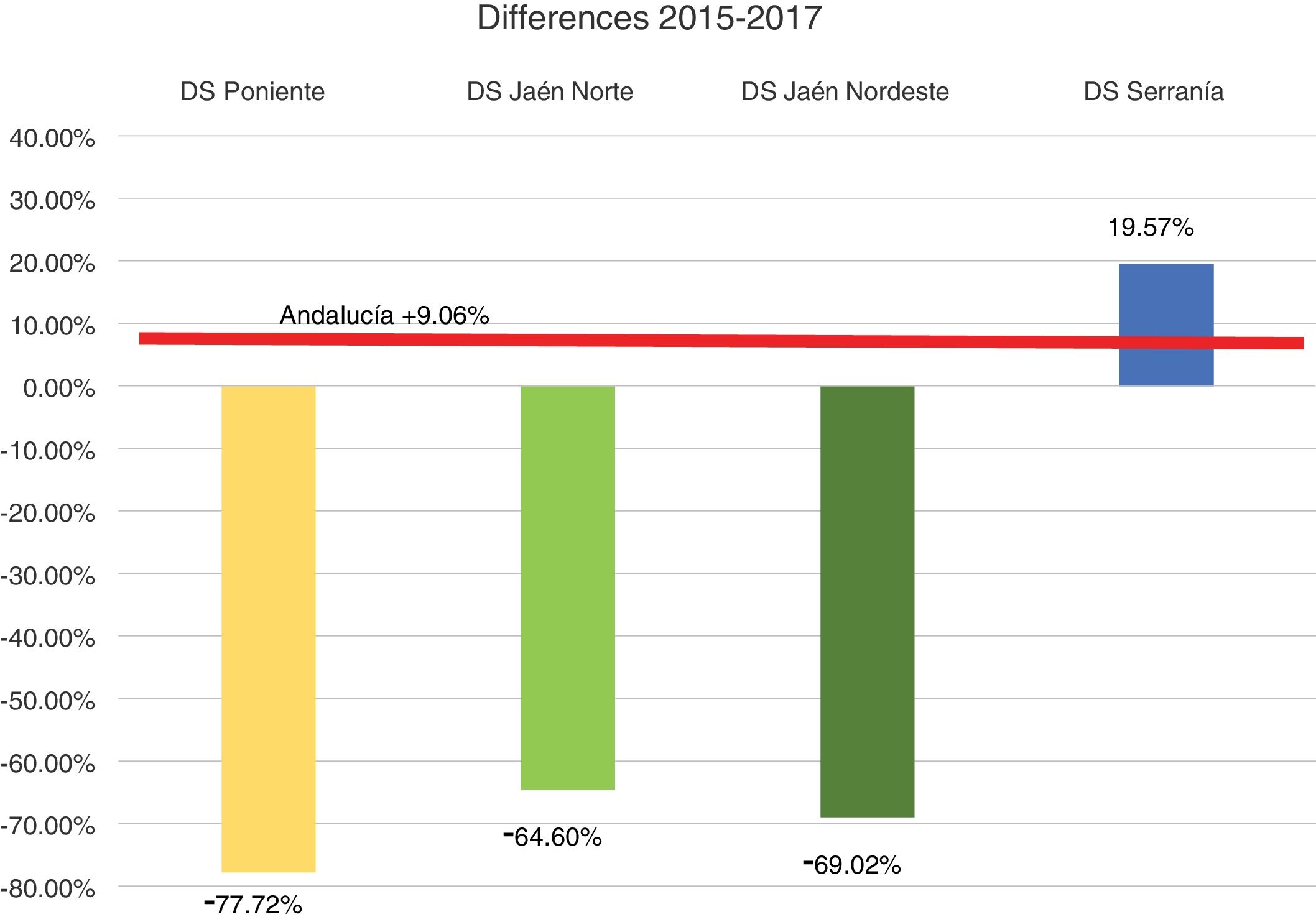

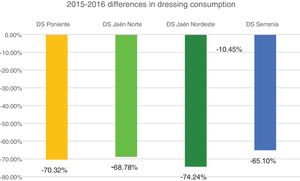

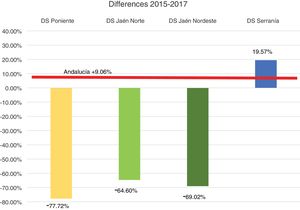

Profitability and rationalization of the cost of dressings compared with the mean in Andalusia is presented in Figs. 4 and 5.

As we may observe, there is a notable and sustained drop during these 2 years, being above 64% in all districts and all periods with the exception of the HD Serranía. The latter had an increase in the last year after a major drop the previous year, possibly related to less time of dedication of the CCW-APN (one day per week).

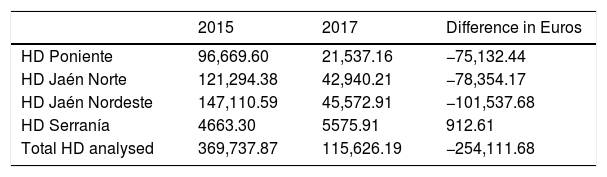

If we translate this cost into euros, in the districts where the CCW-APN have been working and training, this led to a highly important absolute saving, presented in Table 2.

Consumption in euros in the CCW-APN districts.

| 2015 | 2017 | Difference in Euros | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HD Poniente | 96,669.60 | 21,537.16 | −75,132.44 |

| HD Jaén Norte | 121,294.38 | 42,940.21 | −78,354.17 |

| HD Jaén Nordeste | 147,110.59 | 45,572.91 | −101,537.68 |

| HD Serranía | 4663.30 | 5575.91 | 912.61 |

| Total HD analysed | 369,737.87 | 115,626.19 | −254,111.68 |

As we can see, whilst in this period the saving was higher than a quarter of a million euros, the cost rose in the rest of Andalusia.

If we also compare the costs of these districts with those of the 4 closest ones during the 2 years period, in which this figure was introduced, we find there is a difference of 527,994.27 € compared with those which have CCW-APN.

DiscussionA major difficulty when comparing our results to other similar ones is that because this is such as novel figure in Spain there are no data with which to compare. Neither have we been able to find similar studies in the international literature and we must therefore limit ourselves to interpreting the data obtained from this study.19,28–31

We would like to highlight the participation that took place in the 3 analyses, of over 300 nurses and almost 9000 patients between the ADO programme and the nursing homes, a more than representative sample of the real population.

Although prevention data form part of other articles pending publication we would like to highlight the major drop in the prevalence of the number of patients with chronic wounds cared for at home, which in 2015 reached 28.72% and dropped in 2017 to 15.93%, a drop of practically half in the 3 cut-off points of prevalence. This fact should be considered as justification for the creation of the CCW-APN.

The drop appears to be basically due to the introduction of more preventative measure, and could have been conditioned by the training carried out by the CCW-APN to the clinical nurses in the centres which participated in the pilot study of this figure. This training was considered basic and essential right from the start of the creation of this advanced practice project and was a key factor in its development.

Some key notable factors included the volume of consultations received by the CCW-APN by all professionals of different care levels and the increase in care to the most vulnerable people within the healthcare system, both at home and in nursing homes, regardless of the disadvantage this entailed in travelling to districts and areas of healthcare management which were geographically dispersed and required time allotted for it.

The impact of training carried out by the CCW-APNs on treatment adequacy is also outstanding. Better trained professionals are more involved and committed professionals, and this leads to better patient care. We believe the figure of the CCW-APN was therefore greatly reinforced by the proven existence of their knowledge transference to the clinical nurses and from them to the patients.

Specific updated training in wound curing in a humid setting, with specific objectives regarding the correct use of materials depending on the general patent status, the status of the perilesional skin, infection and cost-effectiveness of resources helps to identify the barriers impeding and blocking the normal healing process. Training also establishes specific aims on products for curing in a humid setting (hydrogels, hydrocolloids, hydrofibres, alginates, antimicrobials, silicones, bioactive products, negative pressure therapy, etc.), and the indications, adaptations and contraindications of the materials available to us in the different provincial platforms and their correct usage. This leads to optimisation in matching them and considerable savings in the unit cost of the products used and consumed by platform, compared with the same material used and consumed through a nurse's healthcare prescription.

The outcomes were not the same in all the HD where the CCW-APN was introduced. In Andalusia, we began this pilot study with different models of CCW-APN dedication (full time, 5 days per week, part time, 2 and a half days per week and a limited time, once a week) and the results showed how this dedication significantly affected the outcomes obtained. Effectively, the greater time spent the better the results, with regards to referral rates to hospitals, healing time, prevalence and consumption of materials. This determines that the CCW-APN figure should be introduced full-time.

The CCW-APN is employed in complex and dynamic settings, has continuous and important challenges in offering care to people with CCW. The complete process must be effective, good quality and sustainable and from the results obtained from the pilot study conducted it has become apparent that a full-time CCW-APN would be able to cover a population ranging between 200,000 and 250,000 inhabitants.

Regarding financial savings, in those districts where this figure has been introduced, a saving of over a quarter of a million euros in 2 years has been possible. To this we would add that if we make a comparison between these 4 districts with 4 districts of the same provinces where there the figure of the CCW-APN had not been introduced, the amount doubles. This reiterates the fact that extensive introduction of this figure in all HD in Andalusia would be highly profitable. CCW-APNs are not just an effective resource for healthcare outcomes, they also contribute to the sustainability and equality of the system.

Regarding the limitations of this research, we wish to highlight three. Firstly, the intrinsic factors of the research design. There was no control group as such and therefore risks may have resulted from data collection. As this was a declared practice, one may assume that some professionals would put forward a situation that was better than the real one, and therefore it could be accepted that in the 2 cut-off points the situation put forward was the best possible. However, the managers of the centres offered support for data collection and sent out reminders of the need for their completion, over and above the dissemination strategies carried out by the actual APNs and we think they were able to control this problem.

The other limitation is rotation of professionals. However, the training session was cyclically repeated and in the HD where the APN was introduced they acquired algorithms for taking decisions which remained the same and were available to the newly appointed staff, thus avoiding variability when taking decisions. Furthermore, the APNs were available for contacting individually by any newly incorporated professional.

Finally, we also understand that it may be a limitation that at each cut-off point different patients were included. However we believe that their profile did not vary very much and also that many of them had injuries for long periods of time or even repeated ones and we therefore understand that this limitation is acceptable and our study results do not differ from reality.

ConclusionOur final conclusion from this study is that the prevalence of chronic wounds during the 2 years of CCW-APN implementation decreased by almost half in the districts and areas of reference.

These consultant APNs contribute to the efficiency of care for people with CCW and to the training which optimises the resources and improves professional knowledge, which leads to better care of patients with chronic wounds. Adequacy of treatments increased to 90% in 2017. This implied an increase of almost 25% compared to before the introduction of this figure.

Furthermore, as a result of the planned and structured strategy by the Andalusian Care Strategy, with correct adaptation in the training and action plan for patients with chronic wounds, health expenditure is being rationalised in materials for the care of chronic wounds, thus guaranteeing the sustainability of the Andalusia public health system. This saving may be quantified as being over 250,000 € during these 2 years.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank all the nurses who participated in this project, all the nurses who formed part of the Care Strategy of Andalusia, and all the patients who make our job better every day.

Please cite this article as: Jiménez-García JF, Arboledas-Bellón J, Ruiz-Fernández C, Gutiérrez-García M, Lafuente-Robles N, García-Fernández FP. La enfermera de práctica avanzada en la adecuación de los tratamientos de las heridas crónicas complejas. Enferm Clin. 2019;29:74–82.