Burnout syndrome among intensive care professionals has been widely documented internationally. Few studies address the incidence and prevalence in Latin America. And there are no validated studies about the situation in Argentina. Our goal was to determine burnout prevalence among intensive care nurses in Argentina and related risk factors.

Materials and methodsOnline self-administered survey evaluating demographic variables and the Maslach Burnout Inventory in 486 critical care nurses between June and September 2016.

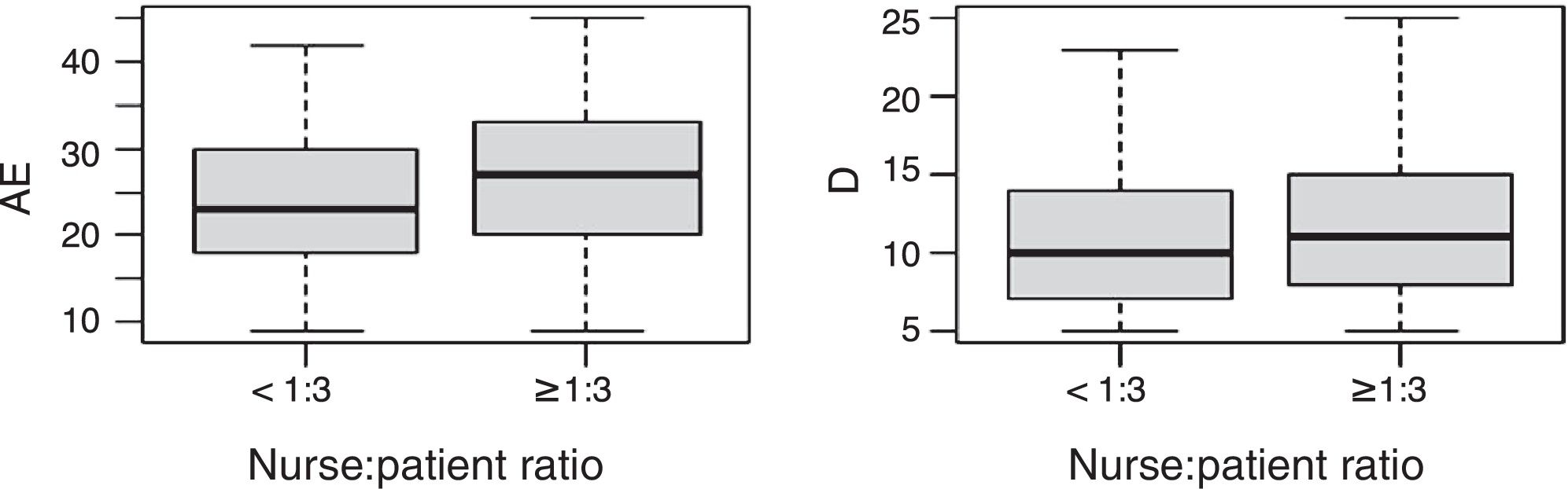

ResultsA percentage of 84.4 of participants show moderate or high levels of burnout syndrome (95% CI 80.8–87.4). No significant association was found between burnout and gender, age, years of practice, academic degree, role or multiplicity of jobs. There was no statistical difference in burnout prevalence among different types of populations of care (neonatal, paediatric or adult care). Nurse to patient ratios of 1:3 or higher was found to be a statistically significant risk factor for emotional exhaustion and depersonalization sub-scales (p=.002 and .0039, respectively).

ConclusionMore than 80% of nurses caring for critically ill patients in Argentina show moderate or high levels of burnout syndrome and this is related to a high nurse:patient ratio (1:3 or higher).

El síndrome de burnout entre los profesionales de cuidados intensivos ha sido ampliamente documentado internacionalmente. Pocos estudios abordan la prevalencia en América Latina, y específicamente en Argentina no existen estudios de peso que aborden esta problemática. El objetivo del presente estudio fue determinar la prevalencia de burnout entre las enfermeras de cuidados intensivos de Argentina y los factores de riesgo relacionados.

Materiales y métodosEncuesta en línea, autoadministrada, para evaluar variables demográficas y puntuación en el Índice de Burnout de Maslach en 486 enfermeras de cuidados críticos entre los meses de junio y septiembre de 2016.

ResultadosEl 84,4% de los participantes presentan niveles moderados/altos de síndrome de burnout (IC 95% 80,8 a 87,4). No se encontró asociación significativa entre el burnout y el género, la edad, los años de práctica, el grado académico, el rol o la multiplicidad de empleos. No hubo diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la prevalencia de burnout entre los distintos tipos de población de atención (neonatal, pediátrica o de adultos). Se encontró que la variable relación enfermera:paciente de 1:3 o más se encuentra estadísticamente relacionada con las subescalas de agotamiento emocional y despersonalización (p=0,002 y 0,0039, respectivamente).

ConclusiónMás del 80% de las enfermeras que tienen a cargo el cuidado de pacientes críticamente enfermos en Argentina muestran niveles moderados/altos de burnout y esto se relaciona con una relación enfermera:paciente≥1:3.

The study of burnout syndrome covers not just the moral, ethical and humanistic aspects of the profession but also the rights of the professional as a worker in protecting his or her own health. Suffering from burnout is not therefore simply a matter of individual vulnerability, weakness, psychological problems, premature stress, etc. but is particularly derived from interaction between the professional and the organisational circumstances of their job.

Burnout is a progressive, dynamic process where certain preceding conditions act as triggers, leading to a dysfunctional response that develops into burnout with disastrous consequences for the worker, their patients, the healthcare system and the community in general.

There are no prior validated studies on this issue in Argentina.

What are the implications of this study?Our aim was to reach a situational diagnosis to subsequently design coping strategies for burnout reduction by determining the prevalence of this syndrome in intensive care nurses in Argentina and its associated variables.

Burnout syndrome (BS) was first described by Freudenberger in 1975 as a feeling of failure and exhaustion, resulting from overwork and which could not be effectively balanced by personal resources, personal energy and coping mechanisms.1 Later, Christine Maslach widened this definition in 1979, describing burnout as the phenomenon resulting from prolonged exposure to interpersonal stress factors within the working and professional environment, characterised by extreme fatigue and the loss of idealism and motivation to work.2 In later studies (2001), Maslach described 3 specific dimensions of burnout: emotional exhaustion, feelings of depersonalisation (cynicism) and lack of progress and inefficacy.3 Burnout is therefore a term used to define extreme exhaustion which is related to decreased interest in work and its associated professional problems. However, people exposed to prolonged, sustained stress at work do not necessarily develop burnout, because if levels of personal achievement, motivation and commitment are maintained it is possible to trigger effective mechanisms to neutralise the effects of stress.4 However, it should be noted that BS is not the same as depression since the former only affects the working or professional sphere whilst depression involves aspects of the person's daily life.5 BS diagnosis comprises 3 components: (1) high levels of emotional exhaustion (EE); (2) high levels of depersonalisation (D), and (3) low personal accomplishment (PA).

In BS, the EE component represents the basic individual response to stress at work. D is the lack of interest in others, or cynicism. Both markers represent the interpersonal context of exhaustion and refer to a negative, insensitive or extremely distant response to the subjects they are caring for. PA is related to commitment, efficacy, efficiency and achieving professional goals, and a low level represents the self perception of burnout made apparent by incompetence, lack of progress and low productivity.6

Intensive care units (ICU) are characterised by generating a considerable amount of work stress due to the high demand for care required by the patients and family members, continuous demand for physical and emotional efforts, complex interprofessional relationships and the high level of training and awareness required to undertake tasks. Many studies have proven that intensive care workers run a higher risk of developing BS,7–10 reporting the relationship existing between high levels of burnout and the appearance of interpersonal conflicts within the care team,11 physical manifestations of disease, emotional problems, high rotation of workers, under-achieving performance, negative attitudes and impairment of care quality.12–14 BS may also affect the results of the care process such as the increase in infections connected to erroneous care.15

The affect of exhaustion on doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals has been widely studied.16,17 This is due to high exposure to stress, especially in the specific areas of intensive care, oncology, palliative care and emergency services.18–21

Poncet et al. studied 2497 intensive care nurses in a multicentre French study and found higher levels of BS related to the following variables: younger nurses, certain organisational models, the quality of interprofessional relationships and aspects relating to end-of-life decisions.22 Verdon et al. studied 97 nurses in a surgical ICU and found that high patient dependency, the type of unit organisation, vocational representation and lack of recognition of nurses were risk factors associated with the development of burnout.23 More recently, Merlani et al. studied 3052 nurses and doctors of the ICU in a multicentre study and found that the age of the nurses (<40 years) and mortality of the patients were risk factors associated with burnout in the subscale of D.24 Guntupalli et al. compared the BS scores between nurses and respiratory therapists in a hospital in Houston and found that the nurses presented with higher levels of BS than the respiratory therapists, particularly those who worked night shifts.25 Embriaco et al. studied 189 ICU and were able to identify that 46.5% of study participants presented with high levels of burnout and found there was a significant relationship between the organisational factors and the quality of interprofessional relations and the prevalence of burnout.26 Zhang et al. conducted a study of burnout prevalence in 17 ICU of 10 fourth level hospitals in Northeast China, reporting that 16% of participants recorded high levels of burnout.27 In the area of critical paediatrics, Lawrence et al. conducted a prevalence study of burnout and its relationship with professionals factors among 232 nurses from critical care paediatric units, 65% of whom demonstrated moderate to high levels of emotional exhaustion, 43% presented with moderate to high levels of depersonalization and 27% demonstrated low levels of PA. Lack of autonomy, leadership and resources were the risk factors leading to burnout found in this study.28

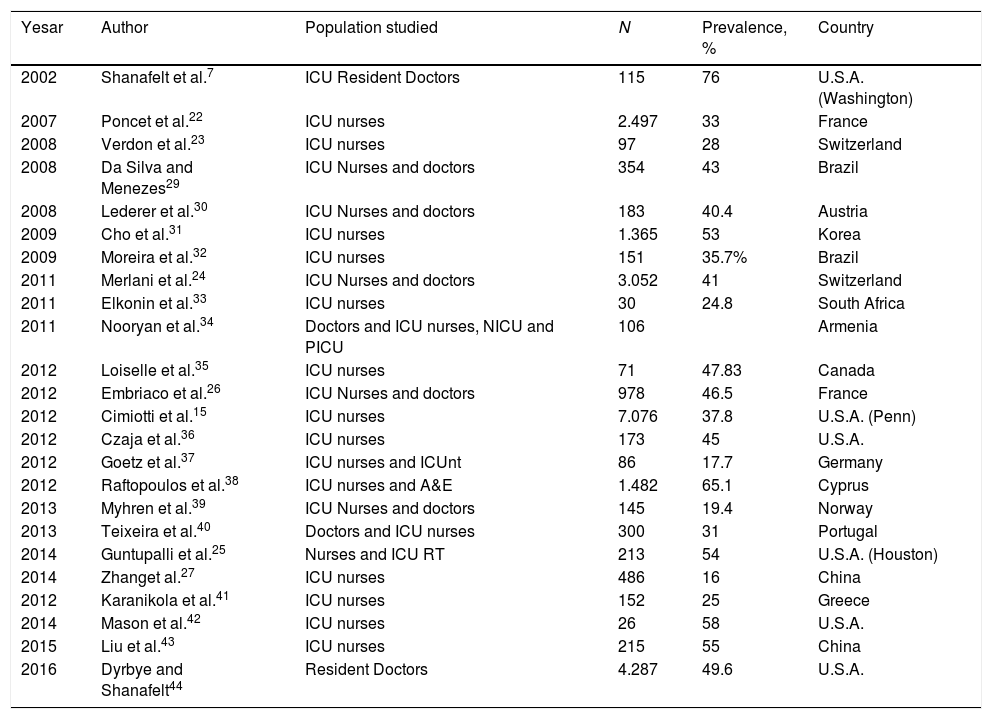

Table 1 summarises the findings from the most relevant studies on BS prevalence.

Prevalence of burnout in the healthcare team in different countries.

| Yesar | Author | Population studied | N | Prevalence, % | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Shanafelt et al.7 | ICU Resident Doctors | 115 | 76 | U.S.A. (Washington) |

| 2007 | Poncet et al.22 | ICU nurses | 2.497 | 33 | France |

| 2008 | Verdon et al.23 | ICU nurses | 97 | 28 | Switzerland |

| 2008 | Da Silva and Menezes29 | ICU Nurses and doctors | 354 | 43 | Brazil |

| 2008 | Lederer et al.30 | ICU Nurses and doctors | 183 | 40.4 | Austria |

| 2009 | Cho et al.31 | ICU nurses | 1.365 | 53 | Korea |

| 2009 | Moreira et al.32 | ICU nurses | 151 | 35.7% | Brazil |

| 2011 | Merlani et al.24 | ICU Nurses and doctors | 3.052 | 41 | Switzerland |

| 2011 | Elkonin et al.33 | ICU nurses | 30 | 24.8 | South Africa |

| 2011 | Nooryan et al.34 | Doctors and ICU nurses, NICU and PICU | 106 | Armenia | |

| 2012 | Loiselle et al.35 | ICU nurses | 71 | 47.83 | Canada |

| 2012 | Embriaco et al.26 | ICU Nurses and doctors | 978 | 46.5 | France |

| 2012 | Cimiotti et al.15 | ICU nurses | 7.076 | 37.8 | U.S.A. (Penn) |

| 2012 | Czaja et al.36 | ICU nurses | 173 | 45 | U.S.A. |

| 2012 | Goetz et al.37 | ICU nurses and ICUnt | 86 | 17.7 | Germany |

| 2012 | Raftopoulos et al.38 | ICU nurses and A&E | 1.482 | 65.1 | Cyprus |

| 2013 | Myhren et al.39 | ICU Nurses and doctors | 145 | 19.4 | Norway |

| 2013 | Teixeira et al.40 | Doctors and ICU nurses | 300 | 31 | Portugal |

| 2014 | Guntupalli et al.25 | Nurses and ICU RT | 213 | 54 | U.S.A. (Houston) |

| 2014 | Zhanget al.27 | ICU nurses | 486 | 16 | China |

| 2012 | Karanikola et al.41 | ICU nurses | 152 | 25 | Greece |

| 2014 | Mason et al.42 | ICU nurses | 26 | 58 | U.S.A. |

| 2015 | Liu et al.43 | ICU nurses | 215 | 55 | China |

| 2016 | Dyrbye and Shanafelt44 | Resident Doctors | 4.287 | 49.6 | U.S.A. |

A&E: Emergency services; RT: respiratory therapists; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; NICU: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit; ICUnt: Intermediate Intensive Care Unit; PICU: Paediatric Intensive Care Unit.

On a regional level, the work which provided the most awareness on the rate of burnout in nurses was that published by Moreira et al., who studied the prevalence of burnout in a hospital of the southern region of Brazil, finding that 42.6% of intensive care nurses presented with high levels of burnout.32

In Argentina there are 179,175 people working as nursing staff of whom 73,373 (40.95%) are nurse technicians, 86,073 (48.03%) nursing assistants and 19,729 (11.02%) graduate nurses.45 There were no official data on what proportion of the total population of nurses were specifically dedicated to intensive care nursing.

Although on a national level there are no published data to describe the situation of burnout in intensive care nursing, Aspiazu qualitatively analyses the problems which most affect nurses in Argentina. He specifically pinpoints work overload, multiple employment situations, infrastructural impairments and low salaries.46

Associated with this is a serious scarcity of nurses, as indicated in the Global Health Observatory of the World Health Organisation in 2018: Argentina presents with a density of 4.21 nurses for every 1000 inhabitants, whilst Brazil has 7.44, United States 9.88 and Germany 13.74 for the same population.47

In the light of this, we proposed to determine the prevalence and risk factors associated with BS in intensive care nurses in Argentina. This study was conducted between the months of June and September 2016.

Materials and methodsA quantitative, observational and cross-sectional study was conducted with nurses who worked in ICU in Argentina between 11th June and 1st September 2016. Given the lack of official data for calculating an intensive care population of nurses, a non probabilistic sample was selected based on the census of members of the Nursing School of the Argentinean Society of Intensive Therapy, a scientific society which centralises all intensive care professionals in Argentina. This census comprised 1005 nurses, who worked in both the public and private sector, caring for the adult, paediatric and neonatal population.

The invitation to participate was sent by electronic mail, which contained a private link to a Google form with 2 sections: one demographic, containing variables such as sex, age, educational level (nursing assistant, nurse technician, graduate or post graduate nurse), years of practice, population cared for (neonatal, paediatric or adult), multi-employment (having more than one full-time job), main function (care, management, research or teaching) and average ratio of nurse:patient in main employment. The other section contained the survey of the Maslach Burnout Inventory, which was adapted and validated by Gil-Monte into Spanish.48 The Maslach Burnout inventory is a scale of 22 items divided into 3 subscales:

- 1.

EE: composed of 9 items which measure the sensation of being emotionally exhausted from demands at work.

- 2.

D: composed of 5 items which measure the degree of distance, feelings and coldness related to the subject of care.

- 3.

PA: composed of 8 items which measure the degree of work satisfaction and feelings of competence.

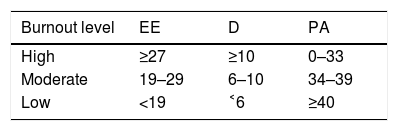

Each item was given a score on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (every day) ‒ the term “burnout” was never included ‒ and the frequency of each experience announced was given a score. High scores of EE and D were associated with a high level of burnout, whilst PA scores were considered inversely, as compensatory. For this study proposal assessment of moderate/high burnout scores as defined by Moreira,32 are shown in Table 2.

Subscales of the Maslach Burnout inventory.

| Burnout level | EE | D | PA |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | ≥27 | ≥10 | 0–33 |

| Moderate | 19–29 | 6–10 | 34–39 |

| Low | <19 | ˂6 | ≥40 |

EE: emotional exhaustion; D: despersonalisation; PA: personal accomplishment.

Adapted from Moreira et al.32

Data were analysed using statistical package R version 3.4.2, and descriptive statistical data were used as markers to analyse the demographic variables.

To establish an association between the presence/absence of burnout and the (categorical) variables that were studied as possible risk factors the exact Fisher test was used. The confidence intervals (CI) constructed to differentiate between proportions and odds ratio are based on normal approximation since the sample sizes guarantee that this approximation be acceptable. To analyse the relationship between the burnout components (EE, D and PA) and the different levels of variables studied as possible risk factors a non parametric method was used (Kruskal–Wallis test based on ranges). In all cases a p value of .05 was established as significant.

To confirm the significant association of the variables we applied the sufficient dimension reduction model and stability selection.49,50

ResultsOut of the 1005 invitations sent, 486 obtained responses, representing a 48.35% rate of response. Data were analysed and a Cronbach test was applied to measure the internal validity of the questionnaire, obtaining a result of .88.

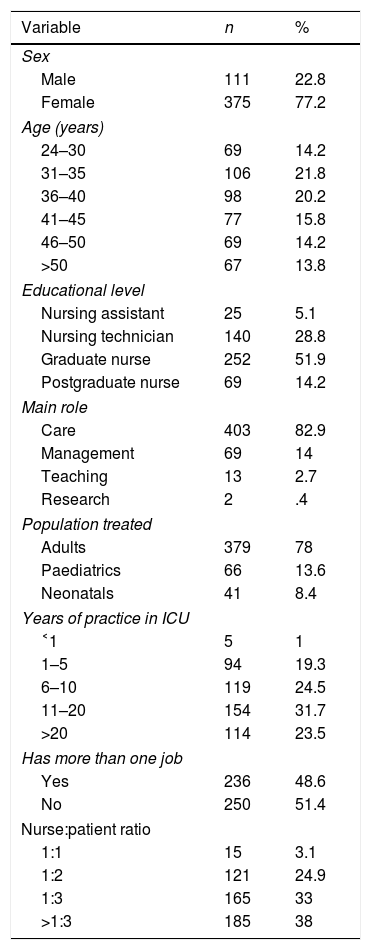

The average participant of the questionnaire was a nurse aged between 31 and 40, a graduate in nursing with 11–20 years of practice, who worked in an adult ICU with a standard nurse:patient ratio of 1:3 or more Detailed demographic variables obtained are contained in Table 3.

Demographic variables studied.

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 111 | 22.8 |

| Female | 375 | 77.2 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 24–30 | 69 | 14.2 |

| 31–35 | 106 | 21.8 |

| 36–40 | 98 | 20.2 |

| 41–45 | 77 | 15.8 |

| 46–50 | 69 | 14.2 |

| >50 | 67 | 13.8 |

| Educational level | ||

| Nursing assistant | 25 | 5.1 |

| Nursing technician | 140 | 28.8 |

| Graduate nurse | 252 | 51.9 |

| Postgraduate nurse | 69 | 14.2 |

| Main role | ||

| Care | 403 | 82.9 |

| Management | 69 | 14 |

| Teaching | 13 | 2.7 |

| Research | 2 | .4 |

| Population treated | ||

| Adults | 379 | 78 |

| Paediatrics | 66 | 13.6 |

| Neonatals | 41 | 8.4 |

| Years of practice in ICU | ||

| ˂1 | 5 | 1 |

| 1–5 | 94 | 19.3 |

| 6–10 | 119 | 24.5 |

| 11–20 | 154 | 31.7 |

| >20 | 114 | 23.5 |

| Has more than one job | ||

| Yes | 236 | 48.6 |

| No | 250 | 51.4 |

| Nurse:patient ratio | ||

| 1:1 | 15 | 3.1 |

| 1:2 | 121 | 24.9 |

| 1:3 | 165 | 33 |

| >1:3 | 185 | 38 |

ICU: Intensive Care Unit.

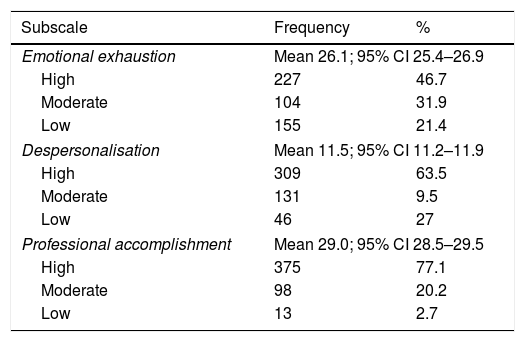

Taking the values of reference for burnout listed in Table 2, we established that 84% of the sample (410 out of 486) showed that they had moderate or high values in at least one of the subscales (95% CI 80.8–87.4). 46.7% presented moderate or high levels of EE, 63.5% had moderate or high levels of D and 77.1% had moderate or high levels of PA.

Table 4 shows the distribution of frequencies for the different levels EE, D and PA, as well as mean values and a 95% CI for these values.

Scores obtained for subscales of burnout syndrome.

| Subscale | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional exhaustion | Mean 26.1; 95% CI 25.4–26.9 | |

| High | 227 | 46.7 |

| Moderate | 104 | 31.9 |

| Low | 155 | 21.4 |

| Despersonalisation | Mean 11.5; 95% CI 11.2–11.9 | |

| High | 309 | 63.5 |

| Moderate | 131 | 9.5 |

| Low | 46 | 27 |

| Professional accomplishment | Mean 29.0; 95% CI 28.5–29.5 | |

| High | 375 | 77.1 |

| Moderate | 98 | 20.2 |

| Low | 13 | 2.7 |

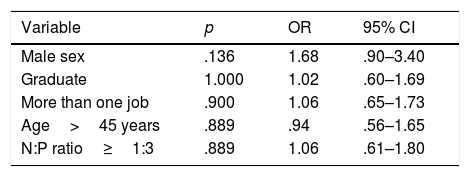

The behaviour of the demographic variables described in Table 3 is almost identical for the group with moderate or high and low values of burnout. No significant differences were found in the calculation of the odds ratio (95% CI, p=.05) for the demographic variables (Table 5). For example, in relation with the variable sex, the prevalence of moderate or high burnout among male nurses was 89,2% (OR 1.68, 95% CI .90–3.40), whilst among females it was 82.9%, but no statistically significant p values were obtained. Similar findings were obtained on analyzing educational level: graduate nurses presented with a prevalence of 81.4% moderate or high burnout whilst nurse technicians presented with a prevalence of 84.2% (OR 1.02, 95% CI .60–1.69). On analyzing the multiple employment variable, 84.7%, of those who declared they only had one full-time job presented with a moderate or high level burnout whilst there was a prevalence of 84% of those who stated they had more than one job (OR 1.06, 95% CI .65–1.73). However, no significant p value could be established for these ratios.

Odds ratio for demographic variables studied.

| Variable | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | .136 | 1.68 | .90–3.40 |

| Graduate | 1.000 | 1.02 | .60–1.69 |

| More than one job | .900 | 1.06 | .65–1.73 |

| Age>45 years | .889 | .94 | .56–1.65 |

| N:P ratio≥1:3 | .889 | 1.06 | .61–1.80 |

N:P: nurse:patient 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

On analysing behaviour the values of EE and D regarding nurse:patient ratio, obtained p values of .002 and .0039, respectively, for a nurse: patient ratio of 1:3 (Fig. 1). As EE and D were categorical variables, no odds ratio was calculated.

To confirm a significant association between the variables, a model for the sufficient reduction of the dimension was applied. This procedure of variable selection meant that it was possible to establish what combination of these was useful for explaining the variability of response. Analysis was limited to that of ordinal variables: age, years of professional experience, proportion of nurses and educational level, since methodology was not applied to nominal regression variables.

On applying this model we found that the EE variables would be explained by the variables of age, years of practice and the nurse:patient ratio. D values could be explained by age, the nurse:patient ratio and level of education. In both cases the estimated coefficient for age is negative, which implies that some older age values corresponded to low values of EE, and D. We also found that age explains the PA variable.

Furthermore, to calculate the statistical weight of these coefficients, a procedure based on stability selection was implemented. We repeated N=100 times the procedure of selection variables with a proportion of data of the 90%, and through a variability simulation study. We obtained for the EE scale, that age is selected 95% of times as a relevant variable, professional experience 87% of times and the nurse:patient ratio 71% of times. To explain D age and nurse:patient ratio were selected every time, whilst to explain PA, the variable age was selected.

DiscussionA response rate of 48.35% was obtained. This percentage is similar to the mean reported in the literature. Authors quote that a low response from professionals caused by a lack of motivation and confidence that the study results change their realities.36,37 Our study confirms that there is a high prevalence of moderate to serious burnout among nurses who perform their services in critical care and that the main variable associated with this is the nurse:patient ratio equal to or higher than 1:3.

Data were obtained from a broad sample of nurses who provide critical care services throughout the country, both in the public sector and the private sector, caring for the adult, paediatric and neonatal population.

The prevalence of burnout is confirmed, as described by several authors7–44 among healthcare workers and more specifically intensive care nurses.

Furthermore, it is possible to establish difference between the variables which other authors link to this phenomenon. Poncet et al. were able to establish that the factors most closely associated with the prevalence of burnout were personal characteristics, organisational factors, participating in research, interpersonal relationships of the team and factors associated with end of life.22

Verdon et al. established that the female sex would be a burnout protector factor, whilst lower levels of training, a lower age and the male sex were associated with higher levels of burnout rates.23

Guntupalli et al. determined that sex, hierarchical position and years of experience had no effect on burnout results, and neither did the risk factor of extra work.25

Our study appears to be in line with that of Guntupalli et al.,5 because we were unable to find significant differences of burnout relating to age or sex. However, we were able to establish a statistically significant relationship between work load (a nurse:patient ratio equal to or higher than 3) and the development of burnout, the latter being an aspect which was not analysed by the previously mentioned authors.

We were also able to demonstrate that although variables such as age, experience in years or level of education had no direct effect on the level of burnout, the association or combination of some of these variables is able to explain to a greater extent the values of one or more scales. Thus EE may be explained by the combination of age and years of practice and D may be mostly explained by age and educational level. In both subcategories, the nurse:patient ratio was always the selection variable.

Our study is also consistent with the reality put forward by Aspiazu relating to working conditions and more specifically work overload, as a characteristic factor of the working reality of nursing professionals in Argentina.46 This is made worse by the critical scarcity of nursing staff, which places extra overburden on the currently active personnel and consequently on greater professional stress and burnout.

ConclusionOur study was able to establish that the majority of intensive care nursing in Argentina presented with moderate or high levels of burnout. No statistically significant association was established between the level of burnout and sex, age, working experience, educational level role or multiple employments. No significant differences were found in burnout between nurses working with adults, paediatric or neonatal patients either.

It was possible to establish that the number of patients per nurse is a variable with impact on burnout levels. Three or more patients per nurse is a statistically significant risk factor for subscales EE and D (p=.002 and .0039, respectively).

Furthermore, we were able to establish that the combination of age (younger nurses), a high nurse:patient ratio and greater number of years of practice could result in higher levels of EE, whilst age (younger nurses), a lower educational level and a high nurse:patient ratio could explain higher D values.

The scarcity of nurses and lack of human resource management strategies to reduce the work load and ensure sufficient number of nurses have led to high levels of stress and burnout.

Urgent changes in organisational models are required, together with the implementation of programmes and models that identify the factors of burnout protection so that this critical health system situation may be overcome.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Our thanks to our colleagues, the main people affected by this terrible situation.

Please cite this article as: Torre M, Santos Popper MC, Bergesio A. Prevalencia de burnout entre las enfermeras de cuidados intensivos en Argentina. Enferm Intensiva. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfi.2018.04.005