The death of a child in the Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) is difficult, the loss generates feelings of sadness and pain; this study highlights the different coping strategies used by nurses to manage this situation and find the strength to provide care at the end of life.

ObjectiveExplore the strategies used by nurses in the PICU in coping with death.

MethodsStudy conducted in the city of Manizales, Colombia, during the months of October, November and December. A qualitative, hermeneutical phenomenological approach was used. The method of intentional sampling for the selection of participating nurses (n=10) working in PICU, in-depth interviews were conducted for the construction of the information and the data were analyzed according to the procedures proposed by Cohen, Kahn and Steeves.

ResultsNurses use coping strategies focused on emotions: they inhibit their feelings towards the patient and their family; they use communication and prayer with the patient, as well as accompaniment to alleviate the suffering of the family.

ConclusionUCIP nurses develop coping strategies for end-of-life care using spiritual resources and communication with the family who require ongoing support, reflecting on death and accompanying the child in its transcendence.

La muerte de un niño en la Unidad de Cuidado Intensivo Pediátrico (UCIP) es difícil, la pérdida genera sentimientos de tristeza y dolor; en este estudio se destacan las diferentes estrategias de afrontamiento utilizadas por las enfermeras para manejar esta situación y poder fortalecerse para brindar cuidado al final de la vida.

ObjetivoExplorar las estrategias de afrontamiento utilizadas por las enfermeras en la UCIP frente a la muerte.

MétodosEstudio realizado en la ciudad de Manizales, Colombia, durante los meses de octubre, noviembre y diciembre. Se utilizó un enfoque cualitativo, fenomenológico hermenéutico. El método de muestreo fue intencional para la selección de las enfermeras participantes (n=10) que trabajan en la UCIP; se realizaron entrevistas en profundidad para la construcción de la información y los datos se analizaron según los procedimientos propuestos por Cohen, Kahn y Steeves.

ResultadosLas enfermeras utilizan estrategias de afrontamiento centradas en las emociones: inhiben los sentimientos frente al paciente y la familia, usan la comunicación y oración con el paciente, así como el acompañamiento para aliviar el sufrimiento de la familia.

ConclusiónLas enfermeras de la UCIP desarrollan estrategias de afrontamiento frente a los cuidados al final de la vida utilizando recursos espirituales y de comunicación con la familia que necesita apoyo permanente, reflexionando ante la muerte y el acompañamiento del niño en su trascendencia.

The literature shows that facing the death of a patient includes facing the pain, agony, suffering and grief of their family. The feelings that nurses experience have repercussions on their professional, working and social life and cause them anxiety and uncertainty. There are studies that address death and coping by family and nurses in the ICU; however, few investigate the death of children and its impact on nurses. This study contributes to the discipline in increasing the quality of the end-of-life care of children, to promote effective coping and functional grief for the family and the nurse.

Implications of the study?The results of this research study serve as a basis for generating curricular changes in undergraduate programmes, since the inclusion of end-of-life care is the tool that promotes quality of care for dying patients and their families, while teaching nurses the appropriate way to cope with the death of their patients, and creating strategies that enable them to get through this difficult situation, and in some way reduce the negative impact on their personal and working lives. This will benefit both nurses and those under their care.

The Intensive Care Unit is where we seek to save the lives of people in critical health situations. However, many deaths occur that involve retaining or discontinuing life-sustaining therapies and, in these situations, the role of the nurse in Intensive Care changes from one of providing life-sustaining measures to end-of-life care.1 Nurses that work in paediatric intensive care units (PICU) are permanently faced with the death of children as well as the need for end-of-life care. They have to face pain, agony, suffering and ultimately the death of their patients, and the grief of their families. The upsetting feelings that nurses experience impact their working and social life2 manifesting as anxiety, uncertainty and emotional exhaustion.3 The way professionals face death and suffering depends on their abilities and personal resources,4 as the same stressful event generates very diverse reactions in each individual.5

The psychological approach to coping was conceptualised by Lazarus and Folkman, who describe it as “constantly changing cognitive and behavioural efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person”.6–8

Coping strategies are divided into 2 large groups according to Lazarus y Folkman6,9 and can be: problem-focussed and emotion-focussed. When they focus on the problem, coping strategies serve to solve problems; this implies the management of internal or environmental demands that pose a threat by decompensating the relationship between person and environment. The function of emotion-focussed coping6,9 is emotional regulation; it includes efforts to modify discomfort and manage the emotional states caused by the stressful event. This type of coping emerges from an assessment from which nothing can be done to modify the injurious conditions of the environment; for example, the death of a child. By contrast, problem-focussed coping appears when the conditions assessed are susceptible to change.

Emotion-focussed coping include several categories, the most noteworthy being9,10: social support, spiritual support, confrontation, escape, release of emotions and cognitive liberation.

Experiencing the death of a child is a complex process, which is difficult to face as it is an individual, private and non-transferable experience.11 Coping with the death of a critically ill child is a process where nurses use emotional resources to be able to adapt.11 Coping capacity and the tools used by nurses will have an impact on the care of the child and their family, and on their own social, occupational and spiritual wellbeing.

This research study, therefore, aims to explore nurses’ coping strategies faced with the death of children in the PICU. The results of the research study will help in understanding care attitudes and to improve nurses’ coping, promoting effective strategies to reduce emotional stress.

MethodThis qualitative, hermeneutical phenomenological research study was conducted to understand how nurses cope with the death of a child in PICU. Qualitative research enables us to develop concepts to help us understand social phenomena, with an emphasis on meanings, experiences and the points of view of participants.12 The phenomenological approach is defined as the comprehension or in-depth knowledge of a phenomenon from experience, until reaching the essence of the participant's experience and of the relationships between experiences.13

Bearing the above in mind, the subjective human experience of nurses working in PICU was considered to describe the coping strategies used when faced with the death of paediatric patients in the unit.

The study was conducted in the PICU of the Meintegral Health Service Provider Institution. This institution is a referral centre for the paediatric population of the Eje Cafetero and surrounding departments, located in the city of Manizales, on the central mountain range of the Andes. The PICU has 12 beds where children with medical and surgical illnesses, as well as children with acute and chronic acute diseases are treated. This variety is what makes Meintegral a suitable place to examine the phenomenon under study.

Convenience sampling was used to select the participants and saturation of information was taken into account, the selection criteria were to be a nurse and have working experience of more than one year in the PICU. The exclusion criteria included being a nurse with no experience of the death of a paediatric patient. There were 10 participants: 8 women and 2 men between the ages of 26 and 38 years. The study objectives and the methodology to be used was explained to each of the participants, who freely agreed to sign their consent; each participant was able to decide and express voluntarily whether they agreed to participate in the study, and they were offered no financial or other remuneration. The investigator exercised no pressure or coercion to achieve greater participation. The investigator announced that the interview would end when they decided; all the interviews were completed with no setbacks. The privacy of the participants and the confidentiality of the information were ensured by avoiding the use of proper names, for which a numbering system was designed to identify each of the interviews.

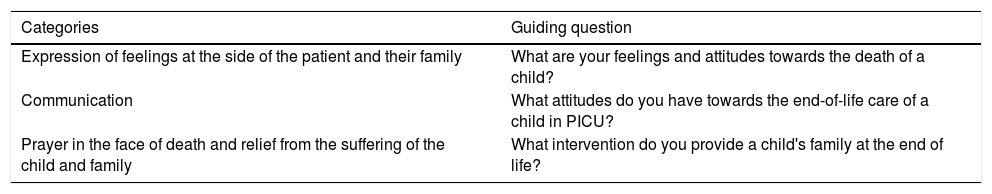

A semi-structured interview was conducted to collect the information, based on a central question, as shown in Table 1. The following questions formed part of each of the interviews according to their content; each were 40 mins in duration with each nurse. The meetings were held during October and November 2017. The results were returned to each of the respondents in December in order to validate each of the categories and interpretations given to the interviews. In all cases the nurses showed willingness to take part in the interviews, thus ensuring the fidelity and credibility of the analysis.14

Guiding questions and categories.

| Categories | Guiding question |

|---|---|

| Expression of feelings at the side of the patient and their family | What are your feelings and attitudes towards the death of a child? |

| Communication | What attitudes do you have towards the end-of-life care of a child in PICU? |

| Prayer in the face of death and relief from the suffering of the child and family | What intervention do you provide a child's family at the end of life? |

The data was analysed according to the scheme proposed by Cohen, Kahn and Steeves.15 The objective was to obtain a description of the coping strategies used by PICU nurses faced with death.

The first step of the analysis was to make a faithful transcription of the interview as soon as it was over, without omitting phrases or expressions of the respondent within their contexts, and to compare it with the recording, which enabled them to be stored on audio, paper and magnetic media.15

The data were then immersed and each interview was read line by line. The initial interpretation revealed general aspects; each of these data was then coded and analysed, which is equivalent to transforming them into significant data.

The topics were labelled separately, on a sheet with the number of the interview and the page from which they were taken, as well as the consecutive number, in order to precisely locate sections of the interview.

Reducing the data led to determining which were relevant for the investigator and they were developed within a conceptual framework that explains the phenomenon in which the respondent was immersed.15 Interpretation of the data shows the point of view of the respondents and the depth that the investigator gave to each of the findings; this reflects reality, but respects what the respondents expressed.

In order to ensure the validity and reliability of the study, a preliminary interview was conducted to assess the investigator's ability to communicate and interact with the respondent. The questions were also assessed to identify those that generated answers that would later enrich the analysis. The revision of the findings by experts with professional experience in intensive care and mental health enabled coping to be examined in greater depth. Likewise, each interview respondent estimated to what extent the procedures used adapted to the reality of the object under study and favoured its replicability.14

The privacy of the participants and confidentiality of the information were protected in this research study by avoiding the use of names, and to that end a numbering system was designed to identify each interview. This study respected the international guidelines relating to the recommendations for research involving human beings contained in the Nuremberg Code,16 the Declaration of Helsinki17 and the Belmont Report.18 It also complied with the recommendations made in Resolution 8430 of 199319 of the Colombian Ministry of Health20 and the Ethics Committee of the Institution.

ResultsCoping refers to a person's efforts to anticipate, challenge, or change conditions, to alter a situation that has been assessed as stressful. Paediatric intensive care units entail countless events that nurses must face, and in particular end-of-life care and the death of patients make these situations difficult to deal with.

The results reveal how the team of nurses working in the PICU have developed coping strategies to deal with the death of children, such as: expressing feelings at the side of the patient and their family, communication and prayer in the face of death, and relief from the suffering of the child and their family.

Expression of feelings at the side of the patient and their familyThe nurses when facing the end-of-life care and death of paediatric patients interpret this situation through their values; in particular, the meaning that each nurse attaches to death (it is a painful event for most) depends on the expression of feelings that in some cases can be visualised in the form of crying alone and with no witnesses. Many of my patients have died and I still cry for every one of my patients, it's not easy to make that decision “Do I keep on doing it, do I stop doing it?” We often believe that what we are doing is the best for the patient, but in reality it is not what they need and we realize that later. I1 It's a painful thing, it's a process that you try to assimilate because often you know that a patient who is going to die, when that time comes …, it is always going to be very difficult. Because to me a child is a person who has just started to live.I3 Sadness and often helplessness. Because as nurses we always try to do our best for a patient to pull through but our efforts are not always the best.I6

Communication is a fundamental pillar in the interaction of the nurse with the paediatric patient at the end of life. It helps the nurse feel at ease when expressing the importance of transcending with death. However, a resource frequently used by nurses relates to the spiritual component, where accompaniment in prayer and strengthening religious belief helps in coping with death. Nursing is this part of accompaniment, like speaking with them, telling them “you’re going to be better on the other side”, “your parents are going to be very sad… but at the moment you’re suffering a lot and as time passes, they won’t forget you… they’re going to remember you, they will keep you in their minds, with the best of memories” then I think that this is care as well. I3 … A child is an inspiration for you and I think that by talking to them, they say that the last thing you lose is your hearing and I think they often listen to you and often there are people who let go of that, but I think that the nursing group should undertake this process and tell them “your mission in life is complete, and now it's time to transcend”. I3 I think it is important to touch the children, to hug them, all of a sudden it's something strange, because I’m not very Catholic, but… I pray and I put holy water on them… I2

Interaction between the nurse and the family creates an environment of tranquillity for each patient. The child's critical state of health produces different feelings, which are expressed by families as: sadness, pain, anguish, which leads nurses to seek conditions under which the family can stay as long as they can with no restriction inside the cubicle, while providing the closeness of spiritual help of some kind within the PICU. There are times when death is inevitable and then I call the parents to accompany the child, to say goodbye, to become part of that grief, to tell the child to be calm, that they should also stay calm, I talk to them, I know that words at that time are hard, but I try to find a way to ensure that they are calm, that the child will be better, that they are not going to suffer. I4

In this situation the family has a bifurcated path and the direction they take depends on the nurse in charge of the child during that shift. Sometimes they are allowed to be next to the patient in the transcendence from life to death, however, nurses acknowledge that at other times it is better for them to be distant, which calls into question whether accompaniment is the most appropriate for the patient and their family. This care is acknowledged as empirical and arises from each nurse's actions in a different way. What we always do as health professionals when a person is critical, in other words: “the family shouldn’t come in”, “friends shouldn’t come in”, “nobody should come in because they are in a really bad way” and we just phone these people when the patient has already died, I believe that this should be reconsidered. I7 So no-one is prepared for loss and grief and still what we do is empirical and often associated with the way you are, the way you want to interact with that family, your daily life, your being, what you are because not all of us will act in the same way. I10

The death of a child generates feelings of pain and loss in the nurses, in some cases they consider this pain their own.11 In this study, crying is described as an expression of helplessness and sadness; the literature describes various emotional responses on the part of nurses towards the death of patients, such as: disbelief, helplessness, loss and guilt,21 feelings that correlate with the findings from the participants in this research study. The nurses deal with these situations using evasive behaviours; they distance themselves from the child and their family, protecting themselves from suffering, “crying alone”.

End-of-life care is a personal experience, each nurse perceives it differently.22 In this study, the nurses use prayer as a means of coping with the death of a patient; in this regard a systematic review found the importance of faith-based spiritual practices an essential mechanism used by nurses to help coping.22

Within spiritual rituals as a coping strategy, nurses refer to using “holy water” along with talking to the patient to enable transcendence, “let them go”; they also use the presence of a spiritual leader if the parents so request, actions that contrast with scientific evidence22 and that help nurses to face death, making the experience easier.11

The family is the cornerstone of end-of-life care, not only because they provide care at home, but also because as they know the patient, their needs and tastes, they can provide that information to the nurses.23

The family group goes through a similar and parallel process to that of the terminally ill child and therefore must be included in care plans. The closeness of the family and their accompaniment in the dying process relieves the patient's suffering and promotes functional family grief.23 However, in this research study the nurses accept that they distance the patient from their family, only allowing accompaniment at the end of the process of when the child has “already died”, a situation that they themselves describe as inappropriate, and suggest the need for this to be changed, i.e., they recognise the importance of the closeness of relatives at the end of life, but do not take actions to promote this. This situation could be improved if nursing staff had adequate undergraduate training in palliative care.

Caring for the family at the end of life is a quality criterion,23 recognising the family caregiver and the group that offers them social support will generate nursing interventions that target them, promoting the relief of fear and increasing their emotional and physical wellbeing,23 and help coping on the part of both the family and the healthcare professional.

Families beg for time to be with the patient, privacy and intimacy, they ask for physical and emotional contact, spiritual support, and the space to express their distress, anger and fears.23 In this research study the nurses acknowledge their lack of preparation for loss and grief, and also the empiricism in acts of care, which depend on specific experience. Recognising the needs of families in crisis, as well as the importance of care plans that include them, will help nurses and families to cope, reducing the stress generated by the situation of crisis experienced.

ConclusionsCaring for paediatric patients at the end of life is a great challenge for nursing staff,24 this process being one of the most stressful in the clinical environment, which requires extensive knowledge and experience,22 elements that are a weakness in the Colombian context and affect how nurses cope.

Nurses in PICU have to permanently face the death of their patients. In order to face this situation adequately, avoiding negative personal and professional impact, it is necessary to strengthen this line of research, since progress in palliative care, end of life and coping with the death of patients might show the importance of including this training in undergraduate programmes.

The end-of-life care received by children in PICU and their families depends on the coping capacity of the nurse in charge. The coping strategies employed can range from distancing (evasive measures) to promoting spiritual support; each nurse uses resources according to their own experience and empirical care is offered in this situation. Being in possession of formal tools will allow for better, humanised care, and functional grief in families and nurses.

End-of-life care competencies not only help patients and their families, they also strengthen nurses’ coping and make the difficult situation of providing care more peaceful as death approaches.

Studies are needed to measure the level of coping by nurses, and the strategies they use to face the death of a critically ill child. This knowledge will contribute to nursing science, increasing the quality of care at the end of a child's life and promoting effective coping and functional grief in families and nurses.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare

The authors would like to thank the participants in this research study for their time and support towards disciplinary knowledge.

Please cite this article as: Henao-Castaño ÁM, Quiñonez-Mora MA. Afrontamiento de las enfermeras ante la muerte del paciente en la Unidad de Cuidado Intensivo Pediátrico. Enferm Intensiva. 2019;30:163–169.