To describe, through an integrative literature review, the factors contributing to the development of burnout and moral distress in nursing professionals working in intensive care units and to identify the assessment tools used most frequently to assess burnout and moral distress.

MethodsAn integrative literature review was carried out. PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, SciELO, Dialnet, Web of Science, Scopus, and Cochrane databases were reviewed from January 2012 to February 2023. Additionally, snowball sampling was used. The results were analysed by using integrative synthesis, as proposed by Whittemore et al., the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme for literature reviews, the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines for quantitative observational studies, and the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist for qualitative research were used to evaluate evidence quality.

ResultsForty-one articles were selected for review: 36 were cross-sectional descriptive articles, and five were literature reviews. The articles were grouped into five-factor categories: 1) personal factors, 2) organisational factors, 3) labour relations factors, 4) end-of-life care factors, and 5) factors related to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey and the Moral Distress Survey-Revised instruments were the most commonly used to measure burnout and moral distress.

ConclusionsThis review highlights the multiple personal, organisational, relational, situational, and end-of-life factors promoting burnout and moral distress among critical care nurses. Interventions in these areas are necessary to achieve nurses’ job satisfaction and retention while improving nurses’ quality of care.

Describir, mediante una revisión integrativa de la literatura, los factores que contribuyen al desarrollo del burnout y del distrés moral en los profesionales de enfermería que trabajan en unidades de cuidados intensivos e identificar las herramientas de evaluación utilizadas con mayor frecuencia para evaluar el burnout y el distrés moral.

MetodologíaSe llevó a cabo una revisión integrativa de la literatura. Se revisaron las bases de datos PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, SciELO, Dialnet, Web of Science, Scopus y Cochrane desde enero de 2012 hasta febrero de 2023. Además, se utilizó el muestreo de bola de nieve. Los resultados se analizaron mediante el uso de la síntesis integradora, según lo propuesto por Whittemore et al. Para evaluar la calidad de la evidencia se utilizó el Critical Appraisal Skills Programme para revisiones bibliográficas, las directrices Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology para estudios observacionales cuantitativos y la herramienta del Joanna Briggs Institute para la investigación cualitativa.

ResultadosSe seleccionaron 41 artículos para su revisión: 36 eran artículos descriptivos transversales y 5 eran revisiones bibliográficas. Los artículos se agruparon en cinco categorías de factores: 1) factores personales, 2) factores organizativos, 3) factores de relaciones laborales, 4) factores de cuidados al final de la vida y 5) factores relacionados con la enfermedad por coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). Los instrumentos más utilizados para medir el burnout y el malestar moral fueron el Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey y el Moral Distress Survey-Revised.

ConclusionesEsta revisión destaca los múltiples factores personales, organizativos, relacionales, situacionales y del final de la vida que promueven el burnout y el distrés moral entre las enfermeras de cuidados intensivos. Las intervenciones en estas áreas son necesarias para lograr la satisfacción laboral y la retención de los enfermeros, al tiempo que se mejora la calidad de los cuidados de enfermería.

What is known/what it contributes

- •

Moral distress and burnout syndrome endanger the sustainability of the ICU workforce, the quality of clinical decision-making, and the care of severely ill patients and their relatives.

- •

The findings of this study synthesized the existing knowledge on the factors contributing to developing burnout and moral distress in ICUs. The appearance of burnout and/or moral distress is influenced by 1) personal factors, 2) organizational factors, 3) factors related to labor relations, and 4) end-of-life care factors.

Implications of the study

- •

Reducing burnout and moral distress would improve the quality of care and patient safety and contribute to job retention.

Healthcare personnel dedicated to caring for or assisting others experience high stress levels, mainly because of the personnel’s specific work characteristics.1 Health professionals under stress experience a series of sensations that include tension, frustration, anxiety, depression, disappointment, abandonment, and demotivation.2 Among the challenges faced by nursing professionals are protecting the patient from harm, providing care that prevents complications, and maintaining a healing psychological environment for patients and their families.3

Achieving these goals becomes particularly complex in intensive care units (ICUs), as these are areas of high work pressure and stress, with extreme situations that require adequate clinical experience and professional maturity to make difficult decisions.4 Frequently, these decisions also have ethical and moral implications that cause moral distress in nurses4,5; moral distress has been identified as one of the leading causes of professional dissatisfaction and exhaustion.6

Starting from the premise that nursing is a moral profession and that nurses are moral agents, Corley3 developed her moral distress theory, in which she defined the factors that can cause moral distress and its impact. Moral distress is understood as the perception of inadequate care and occurs when an individual knows the ethical and appropriate action to take but feels compelled to take another specific action.6 Moral distress can be related to internal limitations (such as doubt, anxiety about creating conflict, and lack of trust) or external restrictions (such as imbalances in perceived power, inadequate communication strategies, and pressure to reduce costs or avoid legal responsibilities).7 Thus, the problems faced during end-of-life care are triggering scenarios for the moral distress of many nurses in ICUs.8

Although some authors have pointed to the beneficial effects of moral distress, such as personal or professional growth and an increased ability for compassionate care,3 most research has focused on the detrimental effects of moral distress.9–11 Moral distress contributes to inadequate care, raises the prevalence of negligence, increases complications in care,12 and reduces patient safety.13–16 Moreover, if moral distress is not resolved, it can manifest as resignation, job dissatisfaction, reduced productivity at work, burnout, or even job abandonment.4,17,18

Growing evidence has suggested that moral distress is one cause of burnout in healthcare professionals,19 especially those working in critical care settings.20–22 Some experts have stated that the most damaging consequence of moral distress is burnout.23,24 Recent studies have reported a significant and positive relationship between these concepts, showing that moral distress is consistently related to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.25 Besides, Maunder et al.26 demonstrated a bidirectional relationship between both. Their study indicated that burnout is consistent with the interpretation that moral distress also contributes to experiencing burnout, perhaps because the depletion of internal psychological resources makes it more difficult to tolerate or respond effectively to circumstances of moral strain or uncertainty. The term “burnout” was coined by Freudenberger in 1974 and later adopted by Maslach in 1978. Burnout has been defined as chronic stress produced by client contact that leads to exhaustion and emotional distancing at work. According to Maslach et al.,27burnout syndrome (BOS) is a multifactorial phenomenon comprising three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal fulfilment. People who experience all three symptoms have the most burnout, although emotional exhaustion has been identified as the hallmark of this syndrome.28

This phenomenon has a relatively high prevalence in the nursing profession, with a notable incidence in ICUs.29,30 Between 23% and 43% of ICU nurses worldwide have been estimated to suffer from BOS.7,31 Additionally, frontline healthcare workers, such as ICU and emergency nurses, were particularly exposed to the consequences of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, where a clear scarcity of the resource capacity of healthcare systems and this lack of available responses to patient needs could also generate ethical conflicts in nursing ICU clinical practice.32 Moreover, some studies have shown that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected the well-being and mental health of nurses.33–35

Various studies36–38 have shown a positive correlation between moral distress and burnout. Considering the relationship between both phenomena and their negative consequences on nurses, patients and organizations, it is of great interest to delve deeper into the factors that influence the development of both moral distress and burnout. However, the literature shows that until now, these concepts have been explored separately. Therefore, this integrative literature review seeks to integrate them to address this gap, increasing our understanding of these concepts to shed light on how to improve nurses’ working environment in the ICU and consequently the care received by patients and their families.

AimsWe conducted the first known integrative literature review to describe the factors that contribute to the development of burnout and moral distress in nursing professionals who work in ICUs. A secondary aim was to identify the assessment tools that have been used most frequently to assess the phenomena of burnout and moral distress.

MethodsDesignAn integrative literature review was carried out. As noted by Whittemore & Knafl,39 the integrative literature review method is an approach that allows for the inclusion of diverse methodologies. Integrative literature reviews are the broadest type of research review method, allowing for the simultaneous inclusion of experimental and non-experimental research to understand a phenomenon of concern fully. The varied sampling frame of integrative literature reviews, in conjunction with the multiplicity of purposes, has the potential to result in a comprehensive portrayal of complex concepts, theories, or healthcare problems of importance to nursing.

As suggested by the same authors,39 the following steps were carried out: problem identification (described in the “Introduction” section), literature search (explained in the “Search methods” section), data evaluation (reported in the “Quality appraisal” section), data analysis (in the “Data abstraction” and “Synthesis” sections) and presentations of findings (in the “Results” section).

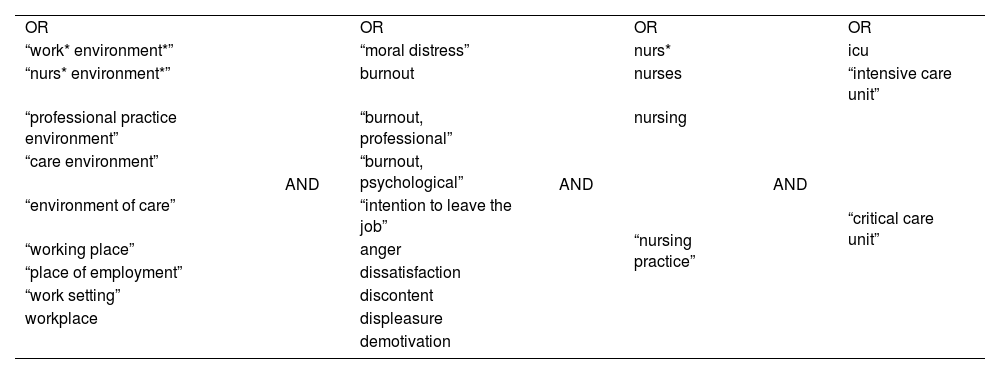

Search methodsA PICO question was formulated: what are the factors that contribute to the development of burnout and moral distress in nursing professionals who work in ICUs? The population corresponded to the nursing professionals who work in ICUs, intervention referred to the factors, there was no comparison group, and the outcome was the development of burnout and moral distress. A bibliographic search was performed in the PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, SciELO, Dialnet, Web of Science, Scopus, and Cochrane databases in February 2023. The following keywords were searched: “workplace”, “burnout”, “moral distress”, “nurse”, and “intensive care unit”. The complete list of search terms and their combination with Boolean operators are shown in Table 1. The limits placed on the search were language (English and/or Spanish) and the years of publication (from January 2012 to February 2023). This time limit was applied to find the most recent scientific evidence. Additionally, the snowball sampling technique was used to avoid missing any articles that could be of interest. It was not considered to have any loss of potentially selectable articles, since in case of not having access, interlibrary loans would be requested to the Library Service of the University of Navarra.

Combination of keywords.

| OR | AND | OR | AND | OR | AND | OR |

| “work* environment*” | “moral distress” | nurs* | icu | |||

| “nurs* environment*” | burnout | nurses | “intensive care unit” | |||

| “professional practice environment” | “burnout, professional” | nursing | “critical care unit” | |||

| “care environment” | “burnout, psychological” | “nursing practice” | ||||

| “environment of care” | “intention to leave the job” | |||||

| “working place” | anger | |||||

| “place of employment” | dissatisfaction | |||||

| “work setting” | discontent | |||||

| workplace | displeasure | |||||

| demotivation |

Limits: language (English and Spanish) and articles published in the past 11 years (from January 2012 to February 2023).

Before the search was performed, the selection criteria were established.

- •

Inclusion criteria: Articles in which the sample consisted of adult ICU nurses; Articles that addressed the causes of the development of burnout and moral distress in nurses; Articles published in the past 11 years; Articles written in English or Spanish; Original articles and systematic reviews.

- •

Exclusion criteria: Articles that focused on non-ICU areas (such as primary care, geriatric hospitalization, oncology, emergencies, and perioperative) or pediatric ICUs; Articles that sought consequences or effects of the demotivation of nurses; Grey literature.

Once each study was read in depth, critical reading tools, including the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) questionnaire,40 the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines,41 and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist,42 were used. The CASP questionnaire was used for the systematic reviews, the STROBE guidelines were used for the quantitative observational studies, and the JBI checklist was used for qualitative research. These instruments aim, on the one hand, to evaluate the quality of the evidence provided by the studies and, on the other hand, to facilitate the synthesis and understanding of the information.

Data abstractionOne researcher (VS) conducted the database searches after agreeing with the rest of the research team on the search strategy. Two researchers (VS and MP) independently reviewed the title and abstract of the articles according to the selection criteria. Any differences in the selection of articles and the subset of articles that would proceed to the in-depth reading phase were agreed upon by the entire research team.

SynthesisThe data extracted from the studies were as follows: study authors and date, country, study aims, study design and data collection (measurement tools), participant characteristics, complete descriptions of the results, and study quality.

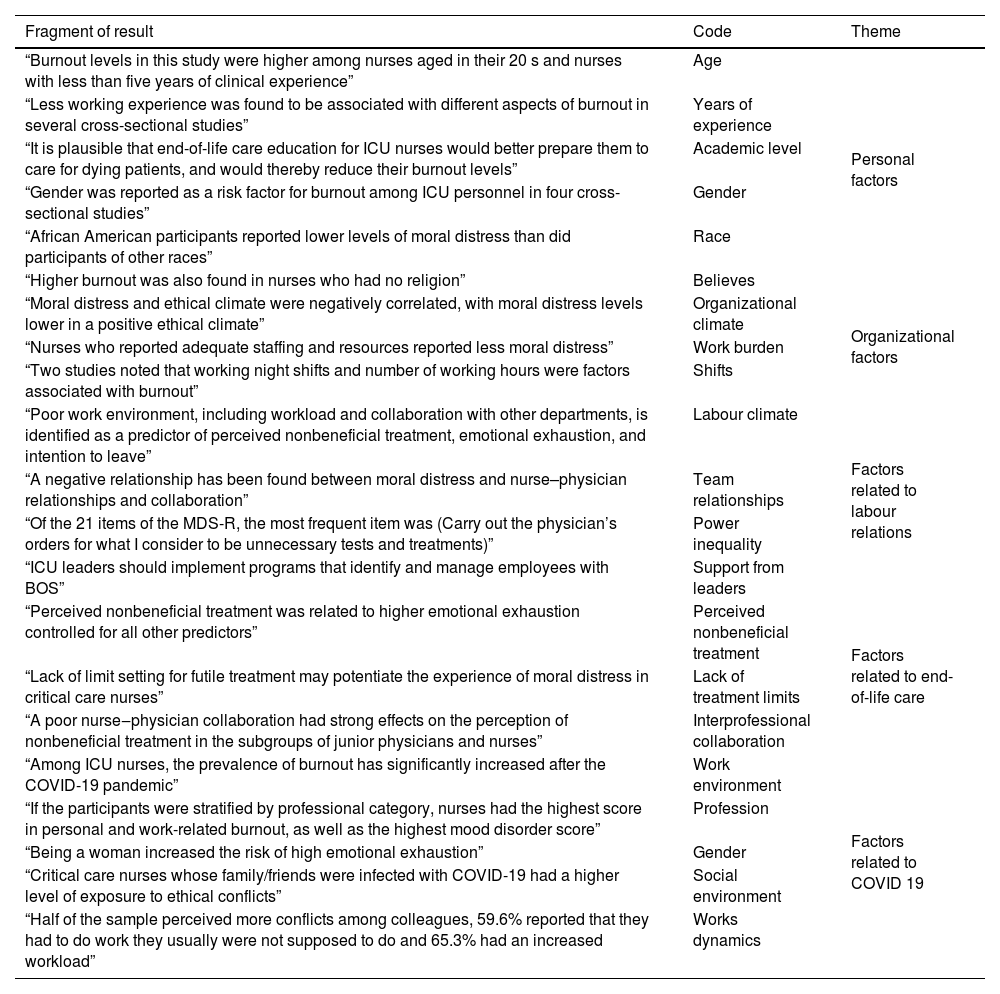

For the data analysis and the knowledge synthesis, an integrative synthesis was performed based on Whittemore43 and Whittemore et al.39 One of the advantages of this approach is the ability to combine different types of research designs to include empirical and/or theoretical literature. We organized, visualized, and compared the data until we integrated the phenomena. The data evaluation stage focused on extracting common themes from the primary studies for later analysis. This process was intended to reach a unified conclusion about the existing research on the problem through constant comparison. This method also helped us explore the similarities and differences between the results of the studies concerning the factors that contribute to the development of burnout and moral distress and to articulate the methodological limitations of the review. This analysis was first performed separately by two of the researchers (VS and MO), and then pooling was carried out with the entire research team to compare, clarify, and reach a consensus on the findings. This process promoted reliability. See Table 2 for an example of this process.

Example of the analysis process.

| Fragment of result | Code | Theme |

|---|---|---|

| “Burnout levels in this study were higher among nurses aged in their 20 s and nurses with less than five years of clinical experience” | Age | Personal factors |

| “Less working experience was found to be associated with different aspects of burnout in several cross-sectional studies” | Years of experience | |

| “It is plausible that end-of-life care education for ICU nurses would better prepare them to care for dying patients, and would thereby reduce their burnout levels” | Academic level | |

| “Gender was reported as a risk factor for burnout among ICU personnel in four cross-sectional studies” | Gender | |

| “African American participants reported lower levels of moral distress than did participants of other races” | Race | |

| “Higher burnout was also found in nurses who had no religion” | Believes | |

| “Moral distress and ethical climate were negatively correlated, with moral distress levels lower in a positive ethical climate” | Organizational climate | Organizational factors |

| “Nurses who reported adequate staffing and resources reported less moral distress” | Work burden | |

| “Two studies noted that working night shifts and number of working hours were factors associated with burnout” | Shifts | |

| “Poor work environment, including workload and collaboration with other departments, is identified as a predictor of perceived nonbeneficial treatment, emotional exhaustion, and intention to leave” | Labour climate | Factors related to labour relations |

| “A negative relationship has been found between moral distress and nurse–physician relationships and collaboration” | Team relationships | |

| “Of the 21 items of the MDS-R, the most frequent item was (Carry out the physician’s orders for what I consider to be unnecessary tests and treatments)” | Power inequality | |

| “ICU leaders should implement programs that identify and manage employees with BOS” | Support from leaders | |

| “Perceived nonbeneficial treatment was related to higher emotional exhaustion controlled for all other predictors” | Perceived nonbeneficial treatment | Factors related to end-of-life care |

| “Lack of limit setting for futile treatment may potentiate the experience of moral distress in critical care nurses” | Lack of treatment limits | |

| “A poor nurse‒physician collaboration had strong effects on the perception of nonbeneficial treatment in the subgroups of junior physicians and nurses” | Interprofessional collaboration | |

| “Among ICU nurses, the prevalence of burnout has significantly increased after the COVID-19 pandemic” | Work environment | Factors related to COVID 19 |

| “If the participants were stratified by professional category, nurses had the highest score in personal and work-related burnout, as well as the highest mood disorder score” | Profession | |

| “Being a woman increased the risk of high emotional exhaustion” | Gender | |

| “Critical care nurses whose family/friends were infected with COVID-19 had a higher level of exposure to ethical conflicts” | Social environment | |

| “Half of the sample perceived more conflicts among colleagues, 59.6% reported that they had to do work they usually were not supposed to do and 65.3% had an increased workload” | Works dynamics |

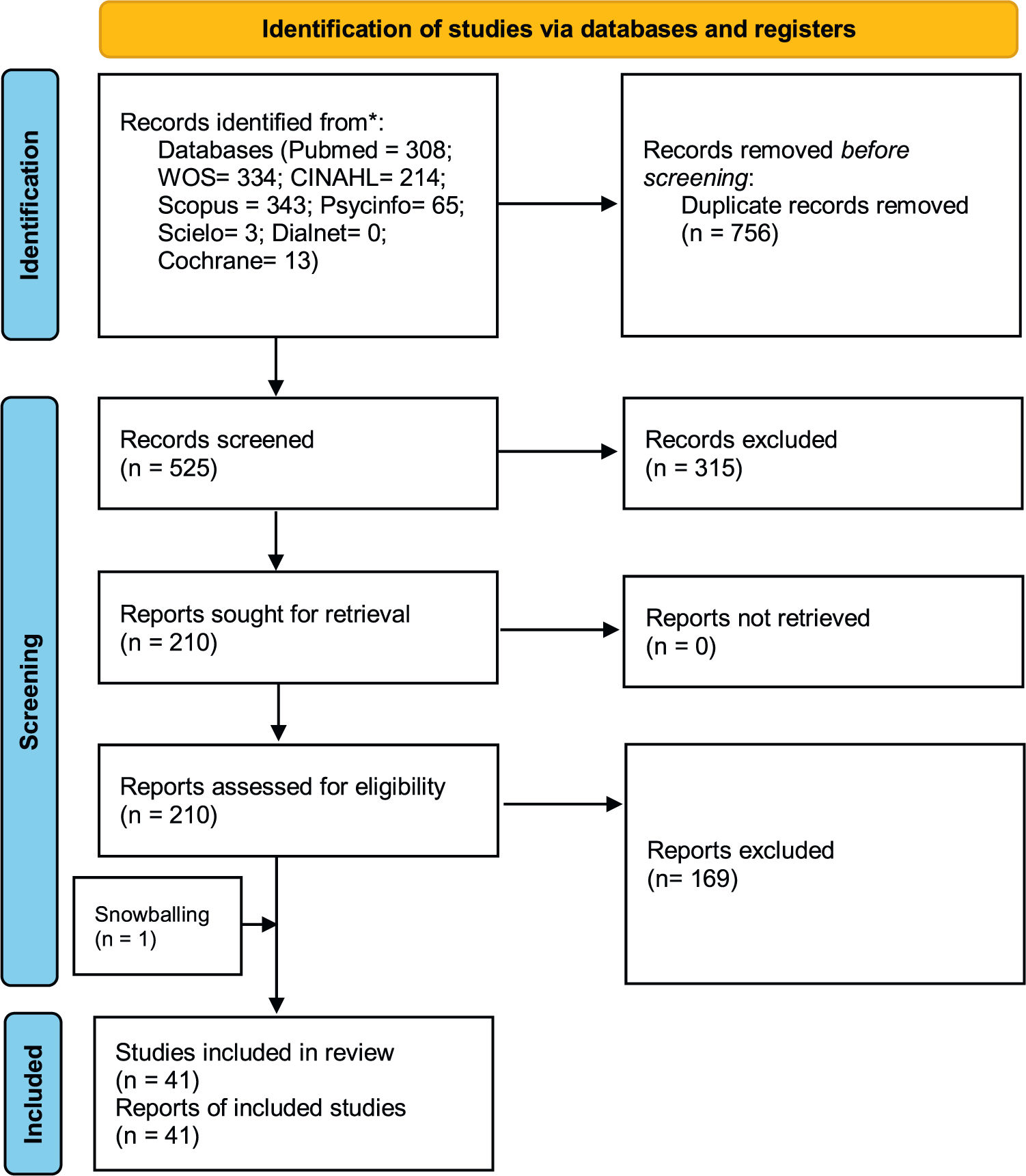

The search resulted in 1281 eligible articles. Two researchers (VS and MP) read the 525 preselected articles in depth; several articles were excluded for not fulfilling the selection criteria. Finally, the other two researchers (MO and JM) corroborated the inclusion of the final 41 studies in the review. The complete selection process is presented in Fig. 1 and was carried out based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Study characteristicsForty-one studies were included in this review. Of these, 36 were cross-sectional descriptive articles,5,8,14,30–32,35,44–72 and five were literature reviews that included quantitative,73 qualitative, and mixed methods articles.4,7,74,75 Regarding the critical appraisal, no studies were removed after the quality assessment evaluation, and in general, the quality of the articles included was high. The methodological characteristics and findings of the included studies are summarized in Table 3.

Summary of the selected studies.

| Author/Year/Country | Objective | Design/Data collection | Sample | Results | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmadi et al., 201430 Iran | To determine the effect of nurses’ workplaces on BOS among nurses. | Cross-sectional study | 100 nurses | - Greater emotional exhaustion in women than in men. | STROBE 18/22 |

| - Scale: (Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey) MBI-HSS | - Greater exhaustion in emergency and ICU nurses than in dialysis and orthopaedic nurses. | ||||

| Alenazy et al., 202144 Saudi Arabia | To examine the relationship between the perception of the nursing practice environment (NPE), job satisfaction and intention to leave (ITL) among critical care nurses working in the state of Ha’il in KSA | Cross-sectional correlational (observational) design | 152 nurses | The NPE was largely favourable (mean (M) = 2.89, standard deviation (SD) = 0.44); however, nurse participation in hospital affairs (M = 2.83, SD = 0.47) and staffing and resource adequacy (M = 2.88, SD = 0.47) scored the lowest. The NPE was found to be significantly correlated with job satisfaction (rs = .287, p value (P) < .01). A significant negative relationship was found between the NPE and the ITL (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rs) = −0.277**, P < .01). However, job satisfaction was associated with ITL (rs = −.007, P = .930). | STROBE 21/22 |

| - Scales: Nursing Workplace Satisfaction Questionnaire (NWSQ) | |||||

| Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI) | |||||

| Turnover Intention Scale (TIS-6) | |||||

| Altaker et al., 20188 USA | To evaluate the relationships between moral distress, empowerment, an ethical climate and access to palliative care in ICUs. | Cross-sectional descriptive study | 238 nurses | - MDS-R scores were from 0 to 225, with a mean (SD) score of 96.5 (55.8). | STROBE 21/22 |

| - Scales: Moral Distress Scale-Revised (MDS-R) | - More knowledge and empowerment were not enough to mitigate moral distress. | ||||

| Psychological Empowerment Index | - Better ethical climates resulted in less moral distress. | ||||

| Hospital Ethical Climate Survey (HECS) | - Work in palliative care increased moral distress. | ||||

| Palliative care questionnaire | |||||

| Aragão et al., 202145 Brazil | To estimate the prevalence of and factors associated with BOS in intensive care nurses in a city in the state of Bahia. | Cross-sectional study | 65 nurses | BOS prevalence was 53.6%; an association was observed with age, tobacco consumption, alcohol use, weekly night shift hours, employment relationship, having an intensive care specialist title, number of patients on duty, monthly income, and considering an active or high-strain job. | STROBE 20/22 |

| - Scale: MBI-HSS | |||||

| Asgari et al., 201946 Iran | To determine the relationship of moral distress and the ethical climate with job satisfaction in critical care nurses. | Descriptive correlational study | 142 nurses | - The mean MDS-R score was 87.02 ± 44.56. | STROBE 18/22 |

| - Scales: Demographic questionnaire | (range 0–336). | ||||

| MDS-R | - A significant relationship was found between the work environment and satisfaction but not between the work environment and moral distress. | ||||

| Olson’s HECS | |||||

| Brayfield and Rothe job satisfaction index | |||||

| Atefi et al., 201447 Iran | To explore factors related to critical care and medical-surgical nurses’ job satisfaction and dissatisfaction. | Qualitative descriptive study | 85 nurses | Three main themes that influenced nurses’ job satisfaction and dissatisfaction are identified: (1) spiritual feeling, (2) work environmental factors, and (3) motivation. | JBI 9/10 |

| Butera et al., 202148 Belgium | To assess the prevalence of burnout risk among nurses before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. | Cross-sectional study | 422 nurses | - The overall prevalence of the risk of burnout was higher among ICU nurses and increased significantly. | STROBE 18/22 |

| To evaluate associated individual and work-related factors. | - Scale: MBI-HSS | - Changes in workload and lack of personal protective equipment were associated with a higher likelihood of burnout risk. | |||

| - Social support from colleagues, superiors, and managers was associated with a lower likelihood of burnout risk. | |||||

| Chuang et al., 201673 China | To determine the prevalence of burnout in ICUs and to identify the factors associated with burnout in ICU professionals. | Review of original articles from observational studies | 25 studies | - Burnout was 35% in Europe and up to 60% in the US. | CASP 10/10 |

| - The prevalence of burnout varied from 6% to 47% (MBI). | |||||

| - Risk factors associated with burnout: | |||||

| - Age < 40. | |||||

| - Single and childless. | |||||

| - Less experience in ICUs. | |||||

| - Organizational factors associated with burnout: | |||||

| - Lack of ability to choose days off, workload > 36 h/week. | |||||

| - Night shifts. | |||||

| - Decision to withdraw life support. | |||||

| - Vulnerable personality. | |||||

| Dodek et al., 20165 Canada | To determine the demographic characteristics associated with moral distress in ICU professionals. | Cross-sectional descriptive study | 428 nurses, 301 physicians, and 211 other health professionals | - MDS (median): nurses: 83 (55, 119); other health professionals: 76 (48, 115); physicians: 57 (45, 70). | STROBE 15/22 |

| - Scale: MDS-R | - Moral distress was greater in nursing professionals than in other groups and was | ||||

| - related to years of experience and | |||||

| - associated with ITL. | |||||

| Emmamally et al., 202049 South Africa | To determine the frequency, intensity, and overall severity of moral distress among critical care nurses working in the critical care environment of a private hospital in South Africa. | Descriptive survey | 74 nurses | Analysis of the relationship between sociodemographic variables and the moral distress composite scores revealed that female respondents experienced higher distress scores than males (P = .013). There was an inverse relationship between composite scores and an increase in age (P = .009) and years of service (P = .022). | STROBE 19/22 |

| - Scale: MDS-R | |||||

| Epp, 201274 Canada | To explore how chronic stressors influence burnout and the forms of burnout prevention. | Literature review | Crucial role of leaders in prevention by creating healthy environments, promoting relationships between disciplines, and debriefing after stressful situations. | CASPE 6/10 | |

| Filho et al., 201931 Brazil | To examine burnout in ICU nurses and nursing technicians. | Cross-sectional descriptive study | 209 nurses in four ICUs of three hospitals | - Nurses presented greater burnout and depersonalization: nurse = 11.05 (3.98) and nurse technician = 9.47 (4.12). | STROBE 20/22 |

| - Scales: Scale of Environmental Practice | - Contributing factors: environment and workload. | ||||

| MBI-HSS | |||||

| Friganović et al., 202051 Croatia | To assess the prevalence of burnout in critical care nurses in Croatia and explore the association of burnout with demographic features. | A cross-sectional study | 620 nurses | Most of the sample were female nursing staff (87.7%), aged 26−35 (38.9%). The results showed that approximately every fifth nurse (22.1%) expressed a high emotional exhaustion, with the lesser burden of a high depersonalization in 7.9%, yet every third nurse (34.5%) scored low on personal accomplishment. Male nurses reported more depersonalization (P = .045), yet neither emotional exhaustion nor personal accomplishment differed by gender. | STROBE 19/22 |

| - Scale: MBI-HSS | |||||

| Friganović et al., 202150 Croatia | To explore the associations between levels of BOS, coping mechanisms, and job satisfaction in critical care nurses in multivariate modelling process. | Cross-sectional multicentre study | 620 nurses | No significant association between gender, coping mechanisms, and job satisfaction was found. However, significant negative associations between burnout and job satisfaction (odds ratio (OR) = 0.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.00−0.02, p-value (P) < .001) and a positive association between burnout and passive coping (OR = 9.93, 95%CI = 4.01−24.61, P < .001) were found. | STROBE 19/22 |

| To explore whether coping and job satisfaction in critical care nurses are gender related. | - Scales: MBI-HSS and the Ways of Coping and Job Satisfaction Scale | ||||

| Guirardello et al., 201714 Brazil | To evaluate nurses’ perceptions of the practice environment and their relationship with burnout. | Cross-sectional descriptive study | 114 nurses | MBI mean (SD): | STROBE 18/22 |

| - Scales: Nursing Work Index-Revised | - Exhaustion 20.74 (6.36). | ||||

| MBI-HSS and Safety Attitude Questionnaire (Short Form 2006) | - Personal fulfilment 30.88 (4.20). | ||||

| - Depersonalization 9.15 (3.39). | |||||

| - Protective factors: autonomy, good relationships with the team, and control over the environment. | |||||

| Habibzadeh et al., 202052 Iran | To determine the level of moral distress and related factors in nurses working in the ICUs of Guilan Province, Iran. | Cross-sectional study | 414 nurses | Most of the studied samples were women (90.6%), married (67.4%), full-time employees (44.6%), undergraduate (90.3%) with M ± SD work experience of 75.69 ± 9.93 months in the ICUs. The mean total score of moral distress was 91.30 ± 65.03 (out of 0−332 scores). Based on the final logistics regression model, gender (OR = 2.410, 95%CI; 1.19−5.6, P = .016) and work experience in the ICU (OR = 0.64, 95%CI; 0.43−0.94, P = .023) were identified as two factors related to moral distress. | STROBE 20/22 |

| - Scale: Corley’s MDS standard questionnaire | |||||

| Hancock et al., 202053 Canada | To explore personal and organizational factors that contribute to burnout and moral distress in a Canadian academic ICU healthcare team. | Qualitative study | 35 participants (21 nurses) | Themes were concordant between the professions and included 1) organizational issues, 2) exposure to high-intensity situations, and 3) poor team experiences. Participants reported negative impacts on emotional and physical well-being, family dynamics, and patient care. Suggestions to build resilience were categorized into the three main themes: organizational issues, exposure to high intensity situations, and poor team experiences. | JBI 9/10 |

| Hiler et al., 201854 USA | To explore the relationships between the severity of moral distress, the practice environment, and patient safety in ICUs. | Descriptive correlational study | 328 nurses | - Greater moral distress resulted in a greater intention to rotate. | STROBE 21/22 |

| - Scales: MDS-R | - Relation between work environment, perception of safety, and quality of care. | ||||

| Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index | - A better environment resulted in less moral distress. | ||||

| Hu et al., 202135 China | To investigate the severity of burnout and its associated factors among doctors and nurses in ICUs in mainland China. | Cross-sectional study | 2411 participants (1289 nurses) | A total of 881 nurses (68.3% of all nurses) were deemed to be burned out. People working in the general ICU were most likely to burn out. Factors associated with burnout included having low frequency of exercise, having comorbidities, working in a high-quality hospital, having more years of work experience, having more night shifts, and having fewer paid vacation days. | STROBE 19/22 |

| Johnson-Coyle et al., 201655 Canada | To describe and compare the prevalence of and factors that contribute to moral distress and burnout among ICU professionals. | Cross-sectional descriptive study | 169 professionals, of whom 77% were nurses | - High levels of stress and BOS in nurses. | STROBE 20/22 |

| - Scales: MDS-R | - Moral distress scores were the highest among registered nurses and nurse practitioners (med [interquartile rating (IQR)] 80 [57−110]) and registered respiratory therapists (85 [61−104]) compared to AH (54 [39−66]) and physicians (66 [43−82], P = .05). | ||||

| MBI-HSS | - The following factors contributed to these results: nonbeneficial treatment, bad relationships with the team, and end-of-life decision-making. | ||||

| Job satisfaction questionnaire | |||||

| Karanikola et al., 201456 Italy | To explore the level of moral distress and the potential associations between indices of moral distress and (1) nurse‒physician collaboration, (2) autonomy, (3) professional satisfaction, (4) intention to quit, and (5) workload. | Cross-sectional study | 566 nurses | - The moral distress was associated with the intention to resign. | STROBE 21/22 |

| - Scales: Corley MDS (CMDS) | - Poor doctor‒nurse collaboration seems to be a fundamental factor that explains the moral anguish of nurses. | ||||

| Autonomy Scale (VAS) | |||||

| Bagg Scale of Collaboration and Satisfaction with Care Decisions (CSACD) | |||||

| Kelly et al., 202157 USA | To identify the key elements of a healthy work environment associated with burnout, secondary trauma, and compassion satisfaction, and the effect of burnout and the work environment on nurse turnover. | Prospective study | 779 nurses | Among the nurses in the sample, 61% experience moderate burnout. In models controlling for key nurse characteristics, including age, level of education, and professional recognition, three key elements of the work environment emerged as significant predictors of burnout: staffing, meaningful recognition, and effective decision-making. The latter two elements also predicted more compassion satisfaction among critical care nurses. In line with previous research, these findings affirm that younger age is associated with more burnout and less compassion satisfaction. | STROBE 21/22 |

| - Scale: Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) | |||||

| Khanal et al., 202232 Spain | To analyse the level of exposure to the ethical conflict of Spanish intensive care nurses and the association of ethical conflict with sociodemographic, labour and COVID-19-related variables. | Cross-sectional study | 117 nurses | - Moderate level of exposure to ethical conflicts. | STROBE 22/22 |

| - Scales: Ethical Conflict in Nursing Questionnaire-Critical Care Version | - The most frequent ethical conflicts were related to “treatment and clinical procedures”. | ||||

| - The most intense ethical conflicts were related to “clinical treatment and procedures” and “service dynamics and work environment”. | |||||

| - Intensive care nurses whose relatives/friends were infected with COVID-19 had a higher level of exposure. | |||||

| Kim et al., 201858 South Korea | To describe the spiritual well-being and burnout of ICU nurses and to examine the relationship between these factors. | Cross-sectional descriptive study | 318 nurses | - The mean burnout score was 3.18 of 5 (range 1.65–5). | STROBE 21/22 |

| - Scales: Spiritual Well-Being Scale and the Pines and Kanner burnout scale (1982) | - Greater spiritual well-being resulted in less burnout. | ||||

| - Professing a religion, being married, having a high level of education, and experience in end-of-life care were associated with less burnout. | |||||

| Klopper et al., 201259 South Africa | To describe the practice environment, job satisfaction and burnout of critical care nurses (CCNs) in South Africa (SA) and the relationship between these variables. | Cross-sectional study | 934 nurses | The high degree of burnout is related to dissatisfaction with | STROBE 20/22 |

| - Scales: RN4CAST | - salaries, | ||||

| MBI-HSS | - opportunities for advancement, | ||||

| - inadequate personnel and resources, and | |||||

| - the lack of participation of nurses in hospital affairs. | |||||

| Lasalvia et al., 202160 Italy | To determine levels of burnout and associated factors among healthcare personnel working in a tertiary hospital in a highly affected area of northeastern Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. | Cross-sectional study | 1961 healthcare workers (687 nurses) | - Burnout was frequent among staff working in ICUs. | STROBE 20/22 |

| - Scale: MBI-HSS | - Compared with those working in non-COVID wards, healthcare staff directly treating COVID-19 patients showed more EE. | ||||

| Lin et al., 202161 Taiwan | Evaluate the state of exhaustion and mood disorder of health workers during this COVID-19 period. | Cross-sectional study | 2029 healthcare workers (301 nurses) | - Among the healthcare workers studied, 44.4% showed moderate exhaustion, and 45.5% showed severe exhaustion. | STROBE 21/22 |

| - Scale: Burnout inventory developed by the Institute of Labour, Occupational Safety and Health, Ministry of Labour of Taiwan and derived from the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory | - Compared to employees during the nonpandemic period (2019), employees working during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020) have higher burnout scores and percentages of severe burnout. | ||||

| - Nurses are more exhausted than other professionals. | |||||

| - Females have higher levels of exhaustion. | |||||

| Liu et al., 201262 China | To examine the relationship between hospital work environments and job satisfaction, work-related burnout, and ITL among nurses. | Cross-sectional study | 1104 nurses | - Burnout and job dissatisfaction are high. | STROBE 20/22 |

| - Scale: MBI-HSS | - Better work environments for nurses were associated with decreased job dissatisfaction and work-related burnout. | ||||

| Iglesias et al., 201372 Spain | To measure the prevalence of BOS, job satisfaction, job stress, and clinical manifestations of stress; and to demonstrate the relationship between these variables among Spanish critical care nurses. | Cross-sectional study | 74 nurses | - Heavy workload and extensive responsibilities but limited authority. | STROBE 19/22 |

| - Scales: MBI-HSS | - Personal and occupational factors. | ||||

| Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS) | - Higher stress but lower job satisfaction. | ||||

| Nursing Stress Scale (NSS) | |||||

| McAndrew et al., 20184 USA | To determine the measurement, contributing factors, impact, and interventions of moral distress. | Literature review | 12 qualitative, 24 quantitative, and six mixed-methods studies | - Inconsistencies in measurements. | CASP 9/10 |

| - Problems of communication and end-of-life care. | |||||

| - Ineffective interventions. | |||||

| Moss et al., 20167 USA | To summarize the available literature and to increase awareness of BOS. | Literature review | Articles published in PubMed and Cochrane in the previous 10 years | - 25%–33% of nurses suffered symptoms of severe BOS. | CASP 8/10 |

| - Nurses, especially ICU nurses, had a higher risk of burnout syndrome than did other health groups. | |||||

| - Related factors | |||||

| Özden et al., 201363 Turkey | To investigate the levels of job satisfaction and exhaustion suffered by intensive care nurses and the relationship between them through the futility dimension of the problem. | Cross-sectional study | 138 nurses | - The application of futility demoralizes health professionals, who had low levels of job satisfaction but high levels of depersonalization. | STROBE 21/22 |

| - Scale: MBI-HSS | - The satisfaction and job sensitivity of nurses are positively affected when they consider that futility does not contradict the purposes of medicine. | ||||

| Panunto et al., 201364 Brazil | To evaluate the characteristics of the professional practice environment of nurses and their relationship with burnout, perception of quality of care, job satisfaction, and the ITL in the next 12 months. | Cross-sectional study | 129 nurses | - The characteristics of the practice environment influence job satisfaction, perception of quality of care, and ITL. | STROBE 20/22 |

| - Scale: MBI-HSS | - Little autonomy, less control over the environment, and having bad relations with the doctor presents a higher level of emotional exhaustion. | ||||

| Purvis et al., 201965 USA | To characterize resilience and burnout among ICU health professionals. | Descriptive study | 55 nurses and 10 physicians | - Among those studied, 45% experienced emotional burnout, and 28% experienced depersonalization. | STROBE 16/22 |

| - Scales: MBI-HSS and the Connor-Davidson scale | - The MBI median (IQR) scores for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment were 8 (6–11), 3 (0–6), and 15 (13–16). | ||||

| - Resilience increased with age. | |||||

| - Catholics had greater resilience. | |||||

| Ramírez-Elvira et al., 202175 Spain | To analyse the levels, prevalence and related factors of burnout in ICU nurses. | A systematic review and meta-analysis | 1986 nurses | The meta-analytic estimate prevalence for high emotional exhaustion was 31% (95%CI, 8%–59%), for high depersonalization was 18% (95%CI, 8%–30%), and for low personal accomplishment was 46% (95%CI, 20%–74%). Within the dimensions of burnout, emotional exhaustion had a significant relationship with depression and personality factors. Both sociodemographic factors (being younger, having a marital status of single, and having less professional experience in the ICU) and working conditions (workload and working longer hours) influence the risk of burnout syndrome. | CASP 9/10 |

| Rivaz et al., 202066 Iran | To determine the relationship between ethical climate and burnout in nurses working in ICUs. | Cross-sectional study | 212 nurses | Ethical climate was favourable (3.5 ± 0.6). The intensity (32.2 ± 12.4) and frequency (25.5 ± 12.4) of burnout were high. Ethical climate had significant and inverse relationships with the frequency of burnout (r = −0.23, P = .001) and the intensity of burnout (r = −0.186, P = .007). Ethical climate explained 5.9% of the burnout. Statistically significant relationships were also found between these factors: age with ethical climate (P = .001), work shifts with burnout (P = .02), and gender and with intensity frequency of burnout in ICU nurses (P = .038). The results of the Spearman correlation coefficient showed significant and inverse relationships between ethical climate and job burnout (r = −0.243, P < .001). | STROBE 21/22 |

| - Scales: Olson’s HECS | |||||

| MBI-HSS | |||||

| Salehi et al., 202067 Iran | To determine the relationship between a healthy work environment, job satisfaction, and anticipated turnover among ICU nurses. | Cross-sectional study | 270 nurses | Healthy Work Environment had a significant and positive relationship with job satisfaction (r = 0.831, P < .001), and a significant but inverse relationship with intention to leave (r = −0.558, P < .001). Marital status had the greatest correlation with job satisfaction and Healthy Work Environment (beta = 0.25, P = .01) and ITL (P < .001, beta = 0.223). | STROBE 19/22 |

| - Scales: Healthy Work Environment (AACN, 2005) | |||||

| Minnesota job satisfaction questionnaire | |||||

| Anticipated Turnover Scale (ATS) | |||||

| Schwarzkopf et al., 201768 Germany | To research the predictors and consequences of perceived nonbeneficial treatment and to compare nurses with junior and senior physicians. | Cross-sectional descriptive study | 778 professionals and 574 nurses | - Perceiving a treatment as nonbeneficial was related to burnout and might increase ITL. | STROBE 21/22 |

| - Scale: MBI-HSS | - Nurses had the highest perception of nonbeneficial treatments. | ||||

| - Nurses and junior doctors reported similar levels of emotional exhaustion (2.6 [2−3.4] and 2.4 [1.8−3.2], respectively; P = .157). | |||||

| Shooride et al., 201569 Iran | To determine the correlation between moral distress with burnout and anticipated turnover in ICU nurses. | Descriptive correlational study | 150 nurses | Mean score of the IMDS was 2.08 + 0.98 (range 0–4). | STROBE 19/22 |

| - Scales: Iranian ICU Nurses’ Moral Distress Scale (IMDS), Copenhagen Burnout Inventory | Positive statistical correlation between distress/burnout and the nurse‒patient relationship, age, work experience, and care ratio. | ||||

| Hinshaw and Atwood’s Anticipated Turnover Scale | |||||

| Demographic questionnaire | |||||

| Teixeira et al., 201370 Portugal | To study the incidence and risk factors of burnout in Portuguese ICUs. | Cross-sectional study | 82 physicians and 218 nurses | - Among those studied, 31% had a high level of exhaustion. | STROBE 20/22 |

| - Scale: MBI-HSS | - Female status increases the risk of burnout. | ||||

| - Higher levels of burnout were associated with conflicts, ethical decision-making regarding treatment withdrawal, and having a temporary employment contract. | |||||

| Tekindal et al., 201271 Turkey | To investigate the levels of burnout of nurses and the unsatisfied needs of the relatives of patients related to nursing care. | Cross-sectional study | 225 nurses and 222 relatives | - Nurses’ burnout levels were high. | STROBE 17/22 |

| - Scale: MBI-HSS | - Younger ages, lack of experience in the profession; lower levels of education; having chosen the profession and the unit in which they work inadvertently; and working in environments, such as intensive care, increases burnout. | ||||

| - As a consequence, family satisfaction decreases. |

The studies were conducted in 17 countries: six studies were from the United States of America4,7,8,54,57,65; five were from Iran,46,47,52,66,69 four were from Canada5,53,55,74 and Brazil14,31,45,64; three were from Spain32,72,75 and China35,61,73; two were from Turkey,63,71 Croatia,50,51 Israel,30,67 Italy,56,60 and South Africa49,59; and one each was from Portugal,70 Germany,68 South Korea,58 Saudi Arabia,44 Belgium,48 and Taiwan.61 The included articles, excluding the literature reviews, involved 13,172 nurses.

Factors impacting burnout and moral distressAfter reading and analysing the selected literature in depth, we grouped the results into five-factor categories that influenced the appearance of BOS and/or moral distress: 1) personal factors (n = 22), 2) organizational factors (n = 25), 3) factors related to labour relations (n = 10), 4) factors related to end-of-life care (n = 11) and 5) COVID period (n = 4). In the final part of the results, the measurement instruments used most in the literature to explore burnout and moral distress are discussed. The selected articles are summarized in Table 3.

Personal factorsProfessional age was a factor to consider, but the results were controversial. Younger people might be more sensitive to job burnout7,52,57,58,71,73,75 because of their lower ability to cope with job requirements and continuous shift changes.73 However, two studies did not find significant differences by age,55,65 and other studies even correlated an older age with a higher risk of exhaustion69 and moral distress.5 Nevertheless, other authors stated that experienced nurses became more skilled and committed, experiencing a lower level of exhaustion.71,73

Additionally, the influence of autonomy and the academic level of nurses are worthy of consideration. Three studies14,58,71 found that less-trained professionals had higher levels of BOS because of a lack of autonomy. However, Altaker et al.8 found that professionals with a diploma in nursing reported less moral distress than those with higher levels of education (bachelor’s and master’s degrees) because nurses with higher degrees were qualified to care for more complex patients.

The professionals’ gender was also considered in some articles, although the results diverged. While few studies found more significant moral distress and burnout among female professionals,4,49,70 others found no significant difference between male and female professions after analysing moral distress and burnout,50,51,55 and others found even lower levels of BOS in female professionals.30,52,73 Another aspect that some studies explored was the link between support systems outside of work and BOS. Being single, having no children, and not having a stable social group increased the risk of exhaustion.7,58,73

Regarding nurses’ places of origin, McAndrew et al.4 found higher levels of moral distress in southern European nurses than in other European nurses. Except for Altaker et al.8 the studies that considered race8,54,65 did not find significantly lower BOS65 and moral distress54 in African Americans. Two studies also evaluated participants’ beliefs and found that being Catholic65 and having spiritual well-being were protective factors, while being agnostic was a risk factor for BOS.58

Concerning the personality traits related to how individuals react to stressful situations in the workplace, the most self-critical, idealistic, perfectionist people were found to have the highest level of commitment.7 Moreover, those who felt more vulnerable or had depression73,75 were shown to have a higher risk of BOS.

Organizational factorsOne of the aspects that was found to influence the motivation of ICU nurses was the organizational ethical climate. This finding reflected the perceived work environment, which could be described as organizational support in ethically challenging situations and related to managing ethical problems in the ICU. Seven studies found that the quality of the perceived work environment was negatively correlated with moral distress,8,15,46,50,59,72 burnout, and dissatisfaction in the workplace,44,47,55 with nurses being the health professionals who were least satisfied with their work.55,73 The study by Rivaz et al.66 showed that although the ethical climate was favourable, burnout was high.

Nurse workload in terms of the complexity of care and the number of beds and resources available was another factor influencing the development of moral distress5,8,76 and burnout.7,31,71,75 In addition, the overwhelming burden that nurses bore was associated with the unpredictable nature of their work and with the considerable time dedicated to patient care; both of these factors contributed to nurse exhaustion by decreasing nurses’ ability to meet demands.35,59,73

To these factors, we must add working days with long and rotating shifts and working nights, which influenced both the recovery time until the next shift and the quantity and quality of rest,73 thereby increasing the risk of exhaustion. These working conditions were found to be related to the following causes of moral distress54 and BOS7,59,73: the perception of having insufficient rewards, the lack of ability to choose days off, and few opportunities to participate in research. A high level of technological development in the hospital also contributed to moral distress 4. Furthermore, belonging to a university hospital was associated with higher BOS.7

Factors related to labour relationsSeveral studies have discussed the impact of the work environment on patient care outcomes and nursing professionals. Six of these studies showed that ICU environments in which the nurse had autonomy, control over the environment, and good relationships with the medical team led to lower levels of burnout, greater professional satisfaction, less intention to leave the job, and better results regarding the quality of care and patient safety.4,7,14,56,64,67 Additionally, Hancock et al.53 reported how personal and organizational factors contributing to burnout and moral distress negatively impacted emotional and physical well-being, family dynamics, and patient care.

Some studies highlighted that ICU nurses needed quick judgement abilities that, together with decision-making abilities about care and responses to different patient needs, could conflict with the perspective of the doctor and/or of families.46,71 The power imbalance (imposed by the hierarchy still present in many organizations) between medical and nursing personnel and the need for obedience to which nurses felt subjected on numerous occasions affected the relationship between these personnel and negatively impacted the quality of care provided.46 A feeling of impotence was considered a fundamental characteristic of moral distress5; this feeling was accentuated if support was lacking from leaders in mediating these conflicts.4,54,74

Factors related to end-of-life careWorking in an ICU has become especially stressful due to patients’ high morbidity and mortality and workers’ regular encounters with ethical problems.7 Notably, due to demographic changes and the chronicity of diseases, nurses increasingly directly participate in the care of terminal patients with a limited probability of recovery. Given this situation, professionals have increasingly been forced to provide treatment that they consider futile or nonbeneficial.68

The phrase “futile or nonbeneficial treatment” has been used to define excessive care that neither benefits the patient nor meets that person’s objectives or expectations.68 In several studies, the perception frequency of nonbeneficial treatment was related to the emotional exhaustion of nurses,55,58,63 moral distress,55 and a greater intention to leave the job; thus, the perception frequency of nonbeneficial treatment was also related to lower quality of care.7,73

Based on this situation, the failure to establish limits for treatment, controversies concerning end-of-life care, and the lack of interprofessional collaboration were shown to further enhance the experience of moral distress among critical care nurses.4,5,55,68

Factors related to the COVID-19 pandemicIt is known that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected the well-being and mental health of nurses, but few studies have analysed how the pandemic affected the risk of burnout in nurses.48

Some studies suggest that compared to employees during the nonpandemic period (2019), employees who worked during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020) had higher overall burnout scores and severe burnout figures; approximately 40% of healthcare employees working during the pandemic experienced burnout.60,61 Professionals in direct contact with COVID patients have been shown to have higher emotional exhaustion.60 In this sense, the overall prevalence of burnout risk increased significantly among intensive care nurses,48 presenting more significant increases in emotional exhaustion than physicians.60 Changes in workload, lack of personal protective equipment,48 and being female were associated with a higher risk of burnout.61

The study by Khanal et al.32 identified no statistical significance between sociodemographic variables and the level of exposure to ethical conflict. However, the authors observed that intensive care nurses whose family members/friends were infected with COVID-19 were more exposed to ethical conflict. In addition, the most intense ethical conflicts were related to “treatment and clinical procedures” and “service dynamics and work environment”.

It should be noted that only three studies studied the phenomena of BOS and moral distress together.53,55,69 However, after integrating all the results, it has been identified that, except for personal factors, where there is more significant variability, common factors influencing the occurrence of BOS and moral distress were identified in the other four themes. Among the organizational factors, the perceived poor quality of the work environment, the excessive workload of the nurses, and rotating shifts with many nights were highlighted. In terms of working relationships, poor team experiences, hostility, lack of inclusion in the team, and disrespect were also found to contribute to BOS and moral distress. Finally, the provision of futile end-of-life care and experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic influenced the occurrence of both phenomena as well.

Measurement scales of burnout and moral distressMost of the studies analysed agreed on the assessment instruments used for measuring both burnout (Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey, MBI-HSS)27 and moral distress (Moral Distress Survey-Revised, MDS-R).17 These instruments were frequently accompanied by demographic questionnaires; satisfaction scales77; and environmental assessments, including the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index78 and the Ethical Climate Survey.79

The MBI-HSS27 was administered in 22 of the studies reviewed.7,14,31,55,65,68,73 This instrument aims to measure the physical and emotional burnout of professionals by evaluating their feelings towards their work. The instrument contains 22 items classified into three subscales: emotional exhaustion, personal fulfilment, and depersonalization. Through this questionnaire, professionals are diagnosed with burnout (low, moderate, or high) if their stress exceeds a cutoff value. Schwarzkopf et al.68 administered the German-validated version of the MBI-HSS, and Filho et al.31 administered the Brazilian-validated version. Most of the studies14,15,30,35,48,50,51,55,59,60,63,64,66,70–73,80 used the original version of the MBI-HSS, while Purvis et al.65 administered the abbreviated version.

The framework that guided Corley3 in developing the Moral Distress Scale (MDS) included Jameton’s conceptualization of moral distress,6 House and Rizzo’s role conflict theory,81 and Rokeach’s theory of values.82 The developed scale was based on research on the moral problems faced by nurses in hospital practice. Subsequently, Hamric et al.83 conducted a review of the MDS to create the MDS-R. With unique tools for each professional group, this scale is the one most commonly used to measure moral distress in health professionals. The MDS-R was administered in seven of the reviewed studies.4,5,8,46,49,54,55 The MDS-R comprises 21 items stratified into two levels (frequency and disturbance level), with items answered on a Likert-type scale (0–5). The last section of the instrument asks whether the respondent intends to leave his or her job or has contemplated changing positions due to moral distress. Six of the studies administered the original version of the scale,4,5,8,49,54,55 while another study administered the validated Iranian version.46

The remaining studies used Corley’s MDS,52,56 the Ethical Conflict in Nursing Questionnaire-Critical Care Version,4,32 the Moral Distress Thermometer,4 the ProQOL,57 and the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory.69 Another scale used to measure burnout was the burnout inventory developed by the Institute of Labour, Occupational Safety and Health, Ministry of Labour of Taiwan; this scale was derived from the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory61 and the Burnout Scale developed by Pines and Kanner.58

DiscussionFor the first time, the findings of this study synthesized the existing knowledge on the factors that contribute to developing burnout and moral distress in ICUs. Specifically, this study identified underlying factors related to the work environment characteristics that, together with personal factors, can increase the risk of having moral distress and/or burnout and that can therefore be an indicator of the quality of the work environment. Below, we discuss the results and reflect on the aspects most attracted our attention.

An important aspect to note is that only three studies have been identified that have studied the concepts of BOS and moral distress together.53,55,69 This is noteworthy given that there is a growing literature that studies the relationship between the two phenomena. Recent studies show that moral distress is likely part of a complex interplay of mediating and moderating factors that develop into burnout.25,84 Therefore, a significant, positive relationship exists between moral distress and burnout,37,85 with moral distress being a significant predictor of all three aspects of burnout.21 However, it should be noted that most of the pandemic-era studies are cross-sectional surveys, so there is a need for further longitudinal research to help determine the factors contributing to moral distress, including dimensions of burnout.26

Delving deeper into the factors that influence exhaustion, Ntantana et al.86 supported the data in the present review because these authors found that personality traits, job satisfaction, and how end-of-life care was practised influenced exhaustion in the ICU. However, the authors added that age and work experience were not associated with any of the dimensions of burnout; this finding contrasts with the results of this review, in which all studies found such an association, except Johnson-Coyle et al.55 In addition, a European survey showed that deficits in interdisciplinary collaboration, a subjectively high work intensity, and more workdays on weekends and per month increased the risk of perceived overtreatment.87 These data were consistent with the results of our study, which showed that long shifts and the perception of an excessive workload promoted BOS.

The scales used in the various studies assessed the role of interpersonal relationships in burnout by assessing the level of depersonalization.27 This phenomenon describes situations where an insensitive/distant reaction is experienced towards peers, patients, and/or family members. Depersonalization can be understood as a protective mechanism for advanced exhaustion.88 As in this review, other studies have indicated the heavy influence of these interpersonal relationships; furthermore, the lack of support from unit supervisors and the lack of recognition by doctors and patients were related to the depersonalization of nursing professionals.89 Difficulties with the medicinal hierarchy experienced by nurses could reduce their achievement.90 In contrast, our review indicates that a better work environment91 and nursing leadership that guarantees this environment92 were related to less emotional exhaustion.

The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) has acknowledged the inseparable link between the quality of the work environment, the excellence of nursing practice, and the results of patient and family care.93 Establishing and maintaining a healthy work environment that fosters respect can be an essential strategy for combatting stress and BOS in the ICU work environment.7 According to a report from the AACN,93 six characteristics are needed to establish and maintain a healthy work environment: (1) skilful communication, (2) true collaboration, (3) effective decision-making, (4) adequate staffing, (5) recognition for work performed, and (6) authentic leadership. In addition, this review and other studies have identified that the lack of specific personal coping mechanisms may contribute to the moral distress associated with BOS.29,94 Therefore, when designing strategies to improve this situation, the factors that should be considered include workload, staffing, number of hours worked, and shift rotation of the nurses in the units.5,73 Additionally, components that improve the work environment should be considered; these components include organizational strategies that allow effective decision-making, collaboration with the team, and authentic leadership.93

Although some studies included in this review identified that the quality of the perceived work environment was negatively correlated with moral distress, Robichaux95 showed that moral distress could be exacerbated in organizations with a deficient ethical climate. For this author, several organizational factors—such as fear of reprisal for actions and/or limited access to ethics resources when dealing with ethical situations, lack of ethical supervisory support, inadequate and/or incompetent staff, and excessive workloads—were sources of moral distress and inhibited its resolution. This author suggested that a lack of supportive leadership could contribute to or directly cause moral distress because if the nurse feels that he or she will not be supported when speaking up in an ethical situation, patient safety may be compromised, and the nurse’s moral integrity may be impaired. Lamiani et al.96 added a lack of participation in decision-making to the causes described by Robichaux95; this factor might cause nurses to feel they are not heard and leave them unable to express their opinions or advocate for their patient’s care.

In relation to end-of-life care, Falcó-Pegueroles et al.97 supported one of the results of this review: having to give a treatment perceived as nonbeneficial was one of the factors that contributed to developing BOS and moral distress in ICU nurses. This result was contrary to another study,98 which concluded that the degree of moral distress was not correlated with end-of-life care and that only the degree of moral distress could explain ethical conflict. This result also contradicted Johnson-Coyle et al.,55 who stated that the degree of moral distress was related more to the disturbance that the distress caused in those who experienced it than the occurrence frequency.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, frontline healthcare professionals have been under tremendous work-related or mental stress.61 The finding that burnout is more prevalent among frontline healthcare workers than among staff working in non-COVID wards contrasts with a recent study conducted in China; this study reported that frontline staff had a lower frequency of burnout than those working in the usual wards.99 We may speculate that the healthcare system in China was more ready than those in other countries to tackle the challenge posed by the COVID-19 pandemic because the system had already developed protocols and procedures to counteract past outbreaks.60 Additionally, unlike a shorter job tenure, night shifts, or lower wages, sociodemographic variables were not associated with an increased risk of burnout in Zhou et al.100

Concerning the scales most frequently used to measure moral distress and burnout, in addition to being valid and useful for cross-sectional measurements, the MDS-R has recently been shown to be sensitive in detecting changes in longitudinal studies in which measurements were taken at 6 months.84 Moreover, although there is almost unanimity in the type of scale used to measure burnout results (the MBI-HSS27), there is no consensus on the interpretation of the results. Precise cutoff values have not been set for critical care providers,7 so the diagnostic criteria for BOS varied among studies, making comparisons difficult. This difference in findings might also have arisen because job satisfaction is affected by moral distress and the different policies of health centres.5,31,73 Ethical priorities and institutional cultural norms influenced how professionals conceptualized autonomy and beneficence, which affected communication about resuscitation decisions and inappropriately aggressive end-of-life care.101 The same was true of the academic level of nurses since differences in the degree required in each country could increase the sample heterogeneity.8

LimitationsThis review has certain limitations, including the analysis of a limited number of databases, the search for articles written only in English or Spanish, and that the reported results and not the original data from the studies were analysed. However, this work has several strengths, including a rigorous search for and selection of articles, an in-depth analysis of the literature found, the presentation of results supported by high-quality research, and important implications for practice.

Implications and recommendations for practiceThis review highlighted the importance of personal, organizational, labour relation, situational and end-of-life care factors in developing burnout and moral distress in nursing professionals who work in ICUs. These results suggested the need to intervene in the work environment, especially regarding organizational factors related to the lack of ethical and supportive leadership. The presence of ethical leaders who serve as mentors and role models for nurses enhances the moral community and could mitigate the causes and effects of moral distress and burnout.95 Future studies should provide tools that empower the ability of these leaders to preserve the moral integrity of nurses by developing and implementing policies and protocols that address the identified concerns, such as provider incompetence or rudeness, insecure staffing, and disturbing behaviours of patients/family members. Future studies should also ensure that nurses are aware of and have access to ethical resources, continuing ethics education, and consultation services.

Moreover, nurses need personal and professional competencies to reduce burnout and moral distress. Health organizations may wish to promote educational and supportive interventions to improve nurses’ empowerment, autonomy, and ethical knowledge; additionally, these organizations may wish to consider effective communication and conflict participation skills and self-care competencies. Ethics education gives nurses the necessary decision-making tools and individual coping skills. Therefore, it can improve self-confidence, reduce fear, and enhance the ability to address complex ethical dilemmas.80 Organizations that provide specific ethical support mechanisms, such as access and support for the use of ethics committees, help nurses learn better and grow after experiencing ethical dilemmas and conflicts. Future interventions in this field may include establishing multidisciplinary ethics rounds and debriefing clinical cases after morally charged events. In addition, helping nurses cope with their environment may include resilience-promoting strategies, such as stress reduction based on mindfulness, self-reflection, self-enhancement awareness, and strong communication.

ConclusionThe findings herein align with or clarify those of previous studies and have important clinical implications that should be considered. Moral distress and BOS endanger the sustainability of the ICU workforce, the quality of clinical decision-making, and the care of severely ill patients and their relatives. Therefore, reducing moral distress and BOS would improve the quality of care and patient safety and contribute to job retention. Thus, this review’s results could help identify aspects to target to prevent moral distress and BOS among ICU nurses. Additionally, the results highlight the importance of support from supervisors and other professionals on the ICU nurses’ team and the importance of strategies focused on improving the work environment and teamwork.

Conflict of interestNo conflicts of interest have been declared by the authors.

Ethical statementThis study is a literature review and therefore no research ethics committee approval is required. No individual's rights have been violated and no participants have been included in the study.

Data availability statementData available on request from the authors.

CRediT authorship contribution statementV. Salas-Bergüés: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. M. Pereira-Sánchez: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. J. Martín-Martín: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. M. Olano-Lizarraga: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization.

We thank the researchers of the “Innovation for Person-Centred Care” (ICCP-UNAV) group of the Faculty of Nursing of the Universidad de Navarra for their contributions to the work discussions.