To analyse the caregivers’ physical, anthropometrical and educational characteristics associated with adequate chest compression and full chest recoil during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

MethodsAn observational prospective research study was conducted. Emergency and critical care health professionals and students performed two minutes of chest compressions on a dummy. Depth and residual leaning after the compressions were assessed and their association with several variables (physical, anthropometrical, and educational) was analysed using logistic regression models.

ResultsTwo hundred thirty-eight volunteers participated. Previous experience of the rescuer in less than six CPRs (OR = 3.03; 95% CI 1.2–7.63) was related to a higher probability of not achieving an adequate depth of compressions. Greater height (OR: .93; 95% CI .87–.99) and grip strength (OR: .94; 95% CI .89–.99) were associated with correct performance of chest compression. We did not find any characteristic related to chest recoil.

ConclusionsThe caregiver’s previous experience with CPR was the strongest factor associated with adequate performance of chest compressions. To a lesser extent, the professional’s height and upper body muscle strength also have an influence. No factors associated with the adequacy of full chest recoil were identified.

Analizar las características físicas, antropométricas y formativas de los reanimadores asociadas a la correcta compresión y reexpansión torácica durante la reanimación cardiopulmonar.

MetodologíaEstudio observacional prospectivo. Profesionales y estudiantes sanitarios de urgencias y cuidados críticos realizaron 2 minutos de compresiones torácicas sobre un maniquí. Se evaluó la profundidad y la presión residual tras las compresiones y se estudió su asociación a diferentes variables (físicas, antropométricas y formativas) mediante la creación de modelos de regresión logística.

ResultadosParticiparon 238 voluntarios. Que el reanimador tuviese una experiencia previa en menos de 6 reanimaciones cardiopulmonares (OR = 0,03; IC 95% 1,2–7,63) se asoció a una mayor probabilidad de no lograr una profundidad adecuada en las compresiones. Una mayor estatura (OR: 0,93; IC 95% 0,87–0,99) y fuerza de aprehensión (OR: 0,94; IC 95% 0,89–0,99) fueron condiciones que actuaron como factores predisponentes a la ejecución de una técnica correcta. Ninguna característica se asoció a la adecuación de la reexpansión torácica.

ConclusionesLa experiencia previa del reanimador es el factor más fuertemente asociado a la correcta ejecución de las compresiones torácicas. En menor medida, también influye la estatura y la fuerza del tren superior del profesional. No se han identificado factores asociados a la adecuación de la reexpansión torácica tras las compresiones.

What is known?

- •

Popularly, it has been argued that there is a relevant relationship between the physical characteristics of the rescuer and the quality of the compressions performed during CPR, both in terms of achieving adequate depth of compression and allowing complete chest re-expansion.

What does this paper contribute?

- •

Anthropometric characteristics of the rescuer have little impact on chest compression performance during CPR.

- •

Previous experience or training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation is the most important factor influencing the correct depth of compressions.

- •

No rescuer factors have been associated with achieving complete chest re-expansion after compressions.

Study implications

- •

Real-time chest compression feedback mechanisms should be considered as an indispensable element during resuscitation.

The chances of survival after a cardiopulmonary arrest depend on multiple factors but, irrespective of other factors, high quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and early defibrillation are the interventions most likely to influence prognosis.1

The parameters that determine high quality CPR are mostly determined by the adequacy of chest compressions. CPR guidelines have been placing special emphasis on the need to perform quality chest compressions, involving the minimisation of interruptions, a frequency of 100–120 per minute, a depth of each compression of at least 50 mm and complete re-expansion of the chest after each compression.2,3 Poor achievement of these indicators may partially explain suboptimal survival outcomes, although this is a potentially correctable problem with corrective measures.

The achievement of these quality objectives may be determined by multiple factors, including, in addition to the patient’s own characteristics (such as chest elasticity), previous training or experience in life support techniques or factors related to the physical condition or anthropometry of the rescuer. Some recent research has already indicated that the weight, height or physical condition of the rescuer are associated with better results in the quality of chest compression,4–6 and may also be related to the achievement of complete chest re-expansion.7 However, the literature on this subject is not abundant and this is a clinical question addressed with different methodologies in different settings.

The aim of this study was to identify and analyse the association between different physical, anthropometric and training characteristics of the rescuer and correct chest compression and chest re-expansion during CPR manoeuvres.

MethodDesignA prospective observational study was conducted. The study obtained a favourable report from the Research Ethics Committee and was conducted in accordance with good practice guidelines.

Scope and subjectsThe study included healthcare professionals (doctors, nurses and emergency health technicians) who carried out their usual practice in the field of emergency or critical care in hospitals or emergency health services in the Basque Country. Also included were final-year nursing students with recent training (less than one year) in life support techniques in the context of their pre-clinical practice in hospital.

Those with a temporary or permanent physical disability related to pathologies or situations that could interfere with the performance of the test, such as musculoskeletal injuries to the limbs or pregnancy of more than 3 months, were excluded.

The sample was obtained through an accidental non-probability system, by advertising the study in two hospitals and requesting the participation of volunteers who met the inclusion criteria. The sampling was complemented by the snowball technique, where the included volunteers invited other colleagues who met the selection criteria to participate. All participants were informed of the aim of the study and gave informed consent.

In the absence of any recent studies applicable to the regional idiosyncrasy on which to base sample size calculations, a pilot test was conducted with 20 participants. Based on the results obtained for the proportion of rescuers under and over 65 kg who performed a mean chest compression depth between 50 and 60 mm, a minimum sample size of 230 subjects was estimated, accepting an alpha risk of .05 and a beta risk of .2 in a bilateral contrast.

Data collectionThe sessions were conducted over 4 months in different clinical simulation laboratories of the Basque Health Service (Osakidetza) and the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) and consisted of 2 min of compressions-only CPR on a Laerdal® Resusci Anne® Q-CPR torso (Stavanger, Norway) placed on the floor and equipped with the standard compression spring (45 kg), controlling the frequency of compressions by means of a metronome at 110 bits per minute. Depth and residual pressure metrics were recorded on the re-expansion of chest compressions delivered by each rescuer using the Laerdal® SimPad with SkillReporter device.

Prior to the start of the simulation exercise, 2 external observers consulted the following data corresponding to each participant: age, sex and whether they had experience in more than 5 real CPRs. Additionally, they determined weight and height, and measured the maximum grip strength of the dominant hand (using a Takei® 5101 hand dynamometer), as an indirect approximation to the integrity and functional strength of the upper trunk.8

The dependent variables in this study were: (a) adequate chest compression (when the mean depth of compressions during the CPR cycle was between 50 and 60 mm) and (b) complete chest re-expansion after compressions (when the mean residual pressure after chest re-expansion was equal to or less than 5 mm, equivalent to 2.5 kg).

Data analysisThe sample characteristics were described using absolute frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables and median and interquartile range for quantitative variables.

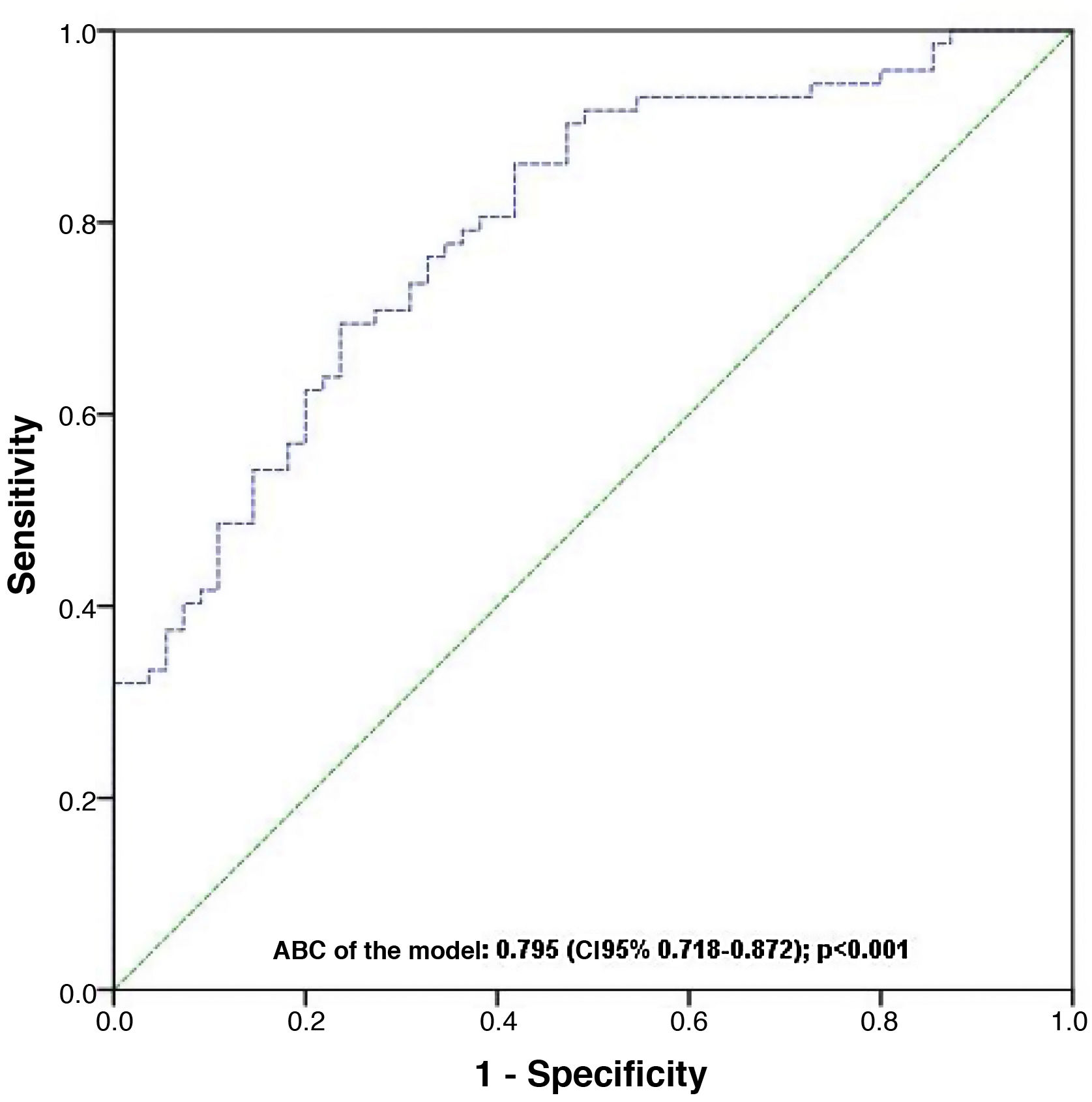

To assess the magnitude of association between rescuer characteristics and the different dependent variables, multivariate logistic regression models were created in which those variables with p < .05 resulting from a previous bivariate analysis were included, obtaining the odds ratio (OR) adjusted calculation and its 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). In the resulting multivariate logistic regression model, 2 continuous independent variables (height and maximum grip strength) and a dichotomised one (previous experience in less than 6 CPR) were introduced. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to determine goodness-of-fit and calibrate the model.

Finally, a diagnostic performance curve (ROC) of the resulting model was performed and the area under the curve (ABC) was calculated.

Statistical treatment of the data was performed using IBM-SPSS® v.25. Statistical significance was considered when the bilateral p < .05.

ResultsA total of 238 volunteers participated in the study, where 190 (79.8%) were female, 156 (65.5%) were under 40 years of age, 58 (24.4%) were undergraduate students and 84 (35.3%) had previously performed more than 5 real resuscitations. The remaining characteristics of the sample are described in Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n = 238).

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Age in years; Me (IQR) | 33 (28–43) |

| Female sex; n (%) | 190 (79.8) |

| Weight in kg; Me (IQR) | 62.5 (55.6–74.1) |

| Height in cm; Me (IQR) | 165 (161–171) |

| Maximum gripping strength in kg; Me (IQR) | 30 (26.5–36.9) |

| Five or fewer previous RCP performed; n (%) | 154 (64.7) |

CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation; IQR: interquartile range; Me: median.

In 92 (38.7%) simulations the mean depth of compressions was between 50 and 60 mm and in 155 (65.1%) the mean residual pressure after chest re-expansion was ≤2.5 kg.

Table 2 shows the results of the univariate analysis for the 2 dependent variables studied. After performing multivariate logistic regression analyses for both effects, no statistically significant factor associated with incomplete chest re-expansion was found. The adjusted regression model created for the variable “inadequate chest compression” yielded 3 statistically significant independent variables: rescuer experience in 5 or fewer CPR situations was associated with an increased risk of inadequacy (OR: 3.03; 95% CI: 1.2–7.63), while greater height (OR: .93; 95% CI: .87–.99) and apprehension strength (OR: .94; 95% CI: .89–.99) were conditions that acted as predisposing factors to the performance of correct technique (Table 3). The ABC-ROC of the model was .795 (95% CI: .718–.872); p < .001 (Fig. 1).

Bivariate analysis of the magnitude of the association between different rescuer characteristics and the adequacy of chest compressions during CPR.

| Inadequate chest compression | Incomplete chest re-expansion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR (95% CI) | P value | Crude OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.00 (.98–1.02) | .92 | 1 (.97–1.02) | .90 |

| Sex (woman) | 7.18 (3.48–14.81) | <.001 | .5 (.26–.96) | .04 |

| Experience (≤5 CPR) | 2.63 (1.52–4.55) | <.001 | 1.35 (.77–2.34) | .29 |

| Height | .91 (.87–.94) | <.001 | 1.03 (.97–1.06) | .85 |

| Weight | .95 (.93–.97) | <.001 | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | .70 |

| Maximum gripping strength | .90(.86–.95) | <.001 | 1.03 (.99–1.07) | .10 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Multivariate logistic regression modelling of factors associated with inadequate chest compression during CPR.

| Coefficient | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experience (≤5CPR) | 1.12 | 3.03 (1.20–7.63) | .02 |

| Height | −.074 | .93 (.87–.99) | .03 |

| Maximum gripping strength | −.064 | .94 (.89–.99) | .03 |

| Constant | 12.681 | .02 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation; OR: odds ratio.

The aim of this study was to determine the characteristics of rescuers that may influence the correct performance of chest compressions during CPR. The previous experience of the professional in other CPR procedures was shown to be the most important factor conditioning the achievement of chest compressions with adequate depth and, to a lesser extent, the height and strength of the upper body. In contrast, no factors were found to be associated with complete chest re-expansion after compressions. In addition, this study also provides evidence that the overall quality of chest compressions performed by healthcare professionals or final-year nursing students has room for improvement.

The information from this experiment, carried out on a sample of healthcare workers who were in a real position to perform CPR manoeuvres in their working context, shows several differences with that of other previous investigations. However, although it is possible to find several articles on this subject in the bibliography, there is great methodological heterogeneity in their approach, which makes it difficult to make a fair comparison between results.

The fact that the rescuer is a woman has been associated in the literature with a lower depth of chest compressions.9,10 Along the same lines as other studies,5 in our study, when the sex factor was adjusted for the other anthropometric variables, it disappeared from the predictive model. This situation may be explained by the fact that sex is not in itself a factor that conditions CPR performance, but it is possible to assume an association between being a woman and having less upper body strength or a shorter average height than men.

The fact that the anthropometry of the rescuer has a direct impact on the quality of chest compressions has been documented by other authors based on bivariate analysis. Weight has been the anthropometric characteristic that in the largest number of publications has been related to correct chest compression or decompression during CPR.6,11 Kessler et al.12 recently found that the body mass index (BMI) of healthcare professionals was related to the ability to achieve adequate depth of compressions (but with no association with chest re-expansion) and Contri et al.7 associated chest compression and re-expansion with gender, weight and BMI when resuscitation was performed by citizens recently trained in basic CPR techniques.

In view of our results, it seems reasonable to think that, independently of the physical characteristics of the rescuer, the factors involved in achieving the quality parameters of cardiac massage may have a greater relationship with experience, training or the development of technical skills. In fact, experiences have been described of additional manoeuvres or skills during CPR that manage to adjust the depth of compressions performed by rescuers with an apparently unfavourable anthropometry.13

As practical aspects, this work may justify the initiation of some strategies aimed at improving the quality of CPR performed by healthcare professionals. Since the importance of previous practical experience in CPR manoeuvres has been demonstrated, special attention should be given to regular training or simulation exercises in life support, emphasising the need for quality compressions. It can be common for healthcare professionals to overestimate their ability and mistakenly believe that the quality of the CPR they perform is higher than the real one.14,15 Teaching based on clinical simulation with real-time feedback mechanisms allows the detection of deficiencies in the technique used that could be easily corrected.16–18 In a complementary manner, it might be appropriate for professionals who habitually attend to CRA situations to exercise their upper body muscles, a recommendation that has also been put forward by other researchers.4,19 Finally, although it is not possible to influence the personal height of the professional, it is worth remembering that appropriate height positioning on the compression plane may favour the correct performance of resuscitation.

LimitationsThis study has some limitations that are worth discussing. Firstly, the time of the experiment was restricted to a single CPR cycle. Under real-world conditions, the same rescuer might have to assume to perform compressions for more than one cycle, so the quality of compressions would certainly have been diminished in such a situation due to fatigue. The same could have happened if the rhythm was not controlled by metronome.20 Finally, the disparity between the number of male and female participants may come as a surprise, but it corresponds to the actual proportion among health professionals in our environment, where approximately 77% of professionals are women.21

ConclusionsBased on the data from this study, it can be concluded that there are some characteristics of rescuers that are associated with the quality of chest compressions. The fact that the health professional has previous experience of less than 6 CPRs is associated with a poorer achievement of the standards of adequate depth of chest compressions. The relationship between greater height and upper body strength and chest compression depth is limited. However, the physical characteristics or experience of rescuers do not seem to have a determining influence on achieving adequate quality parameters for chest re-expansion during CPR.

FinancingThis study was funded by the Organización Sanitaria Integrada de Bilbao-Basurto (Osakidetza – Basque Health Service), grant code: OSIBB 19/015.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

To Iraia Isasi, Elixabete Aramendi, Unai Irusta, Ander Herreros and Eider Díez, for their help in the fieldwork and in data extraction.