Nurses play an essential role in the care of emergency hospital patients, being the ones who have the most contact with the patient and the first to be able to detect their imminent deterioration. However, the literature shows the impact that this can have in terms of stress and insecurity among new nurses, with the consequent risk of resignation in the institution and in their learning process.

AimsTo explore the process of incorporation of new nurses in the emergency room, as well as to identify and understand their emotions, difficulties, needs and proposals for improvement.

MethodsQualitative research aimed at emergency room nurses in a tertiary level university hospital in Catalonia, between April 2022 and March 2023. Twelve semi-structured interviews were conducted with content analysis.

ResultsFour categories emerged: identification of deficiencies, emotional dimension, competencies of the expert nursing professional, and needs and proposals for improvement, as main themes.

ConclusionsInsufficient training and deficit of interdisciplinary communication skills appear as main stressors. The analysis of the results suggests the need to create an intervention program that protects the mental and emotional health of new nurses and ensures the integrity of their patients. Innovative and multimodal training adapted to generational change is called for, with virtual, immersive, and contextualized simulation scenarios, together with the implementation of tools such as debriefing and nursing clinical sessions.

Las enfermeras desempeñan un papel esencial en la atención al paciente emergente hospitalario, siendo las que mayor contacto tienen con el paciente y las primeras en poder detectar su deterioro inminente. No obstante, la literatura evidencia el impacto que ello puede suponer en términos de estrés e inseguridad entre las enfermeras principiantes, con el consiguiente riesgo de claudicación en la institución y en su proceso de aprendizaje.

ObjetivosExplorar el proceso de incorporación de las enfermeras principiantes en el box de emergencias, así como identificar y comprender sus emociones, dificultades, necesidades y propuestas de mejora.

MétodoInvestigación cualitativa dirigida a las enfermeras del box de emergencias en un hospital universitario de tercer nivel, en Catalunya, entre abril de 2022 y marzo de 2023. Se realizaron doce entrevistas semiestructuradas con análisis de contenido.

ResultadosEmergieron cuatro categorías: identificación de carencias, dimensión emocional, competencias de las enfermeras expertas; y necesidades y propuestas de mejora, como temáticas principales.

ConclusionesLa formación insuficiente y el déficit de habilidades de comunicación interdisciplinar aparecen como principales factores estresantes. El análisis de resultados sugiere la necesidad de crear un programa de intervención que proteja la salud mental y emocional de la enfermera principiante y asegure la integridad de sus pacientes. Se reclama una formación innovadora y multimodal adaptada al cambio generacional, con escenarios de simulación virtual, inmersiva y contextualizada, junto con la implantación de herramientas como el debriefing y las sesiones clínicas de enfermería.

The current evidence warns of the lack of preparation felt by nurses when they start work in critical care units. They recognise that their previous training is insufficient for the care they have to provide, with the consequent risk to the patient.

The study consolidates the great complexity involved in starting to work in critical care units, putting the mental health of novice nurses at stake. However, this can be attenuated with the promotion of specific training and support strategies, as the results obtained show.

Implications of the studyThe need for innovative and multimodal training adapted to generational change is evident, with complex and contextualised simulation of scenarios of emergent situations, where more levels of support are offered, not only clinical, but also social and emotional.

Emergency care units in hospitals serve users who need higher level and ongoing care. This requires health professionals to have a good knowledge of critical patient management, since their actions directly influence the progression and outcome of this type of patient. In the critical care process, fast response times and knowledge and management of new technologies are necessary, which add to the complexity of acute care.1,2 This puts nurses in a stressful situation, as they must identify and assess any deviation from a clinical picture of health or illness. This complex process is decisive for the survival of patients, and requires experienced nurses who provide immediate and quality care.3

Patricia Benner’s model for decision making suggests that technical expertise and the process of acquiring skills over clinical knowledge is paramount. The model consists of 5 stages: novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and expert.1,4,5 Based on this model, various scientific contributions warn of the insufficient prior training perceived by the professionals with respect to the care they must deliver when starting to work in critical care units.6–9 However, the main pillars that positively influence the learning process are the experience of participating in emergency situations, organising the integration of technology in care, clinical judgement, and the acquisition of skills.10–13 The literature also highlights the importance of including simulation, with contextualised scenarios, as a tool to improve the learning curve of professionals.11,14

The literature also suggests a need for training that is closer to reality, with real clinical cases and in different contexts, where the main focus is not so much on general competencies but on more specific care, thus highlighting the importance of multidisciplinary work.12,13 The proposal in these training programmes is to integrate people and technology, promoting holistic and dual training programmes between patients and machines, while stimulating critical and reflective thinking.15–17 Various contributors propose the implementation of clinical sessions by and for nurses, where experiences are presented to help professionals to be prepared in the event of an emergency. The creation of clinical sessions as a tool for improvement favours the exchange of knowledge and reflective thinking, incorporating scientific evidence, and the consolidation of procedures.17,18

Another aspect highlighted in the literature about the training programme is the integration of social tools to facilitate communication between novice and expert nurses.1,15 The simulation of cases formed by interprofessional teams – doctors, nurses, healthcare assistants, etc. – helps foster these interpersonal relationships, teamwork, and patient safety.11,19 In addition, the integration of psychological interventions is proposed to encourage support among colleagues, so as to reduce symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress, thus lowering dissatisfaction and the risk of job burnout. These aspects also make it possible to stimulate professionals’ emotional intelligence, which is directly related to job stability.15,16

Investigating the experiences of new nurses in critical care units, finding out how they face the process of incorporation, the support they have found, and the resources they have put in place to manage the situation are the guidelines needed to create innovative training programmes aimed at the real needs of the professional collective. We start from the hypothesis that novice nurses starting work in emergency bays suffer a high level of stress and insecurity, which affects both their professional practice and their mental health. Based on Patricia Benner's model, the aim of this article is to explore the process of incorporation of novice nurses in the emergency bays, and to identify and understand their emotions, difficulties, and needs and put forward proposals for improvement of the current induction plan. The aim is to promote training and support strategies to empower novice nurses on their journey to excellence and good practice.

MethodDesignThis is a qualitative study with a descriptive approach, based on the phenomenology framework. It includes the use of semi-structured interviews with content analysis.

Phenomenology refers to a methodological approach focused on understanding individuals’ experiences from their perspective, based on their interpretation of the facts, their awareness and their reflections; in other words, it attempts to explain qualitatively the meaning that individuals attach to the social phenomena they experience in their lives, which is useful for our research.20

Scope of the studyThe study was conducted in a tertiary university hospital between April 2022 and March 2023. The specific context were the emergency bays of the emergency department, itself comprising 5 bays where patients with emergent conditions are treated, with a nurse/patient ratio of 1:2.

SubjectsTheoretical purposive sampling was used among the novice nurses in the emergency department. The aim of this type of sampling was to obtain in-depth knowledge of the phenomenon under study.21,22 The sample size was based on a population of 46 nurses from the different shifts working in the emergency department and practising in the emergency bays, of which 19 professionals were eligible to participate after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The following inclusion criteria were established: (1) length of service in the emergency bays of less than one year, and (2) working as a registered nurse with a degree or diploma. The exclusion criteria were those working as contracted nurses in critical care units or outpatient services.

The candidates were contacted personally and, after verifying that they met the selection criteria and had agreed to participate voluntarily, and providing them with the information sheet and informed consent form, they were invited for interview. To provide heterogeneity of discourse, we considered professionals of different ages, sexes, studies, and work shifts.

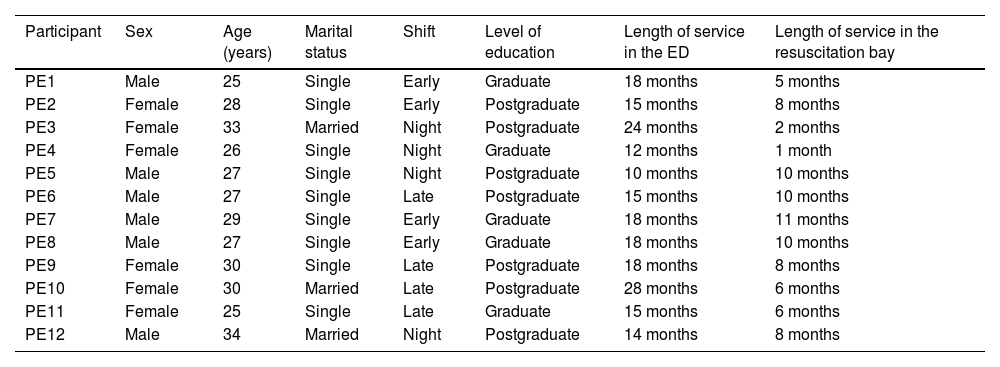

The final sample was formed progressively during the course of the research, until saturation of categories,21,22 because no information other than that collected was obtained and it became repetitive after open coding, resulting in a final sample of 12 participants, with variability in sex, age, and training (Table 1).

Data of the nurses working in the resuscitation bays.

| Participant | Sex | Age (years) | Marital status | Shift | Level of education | Length of service in the ED | Length of service in the resuscitation bay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE1 | Male | 25 | Single | Early | Graduate | 18 months | 5 months |

| PE2 | Female | 28 | Single | Early | Postgraduate | 15 months | 8 months |

| PE3 | Female | 33 | Married | Night | Postgraduate | 24 months | 2 months |

| PE4 | Female | 26 | Single | Night | Graduate | 12 months | 1 month |

| PE5 | Male | 27 | Single | Night | Postgraduate | 10 months | 10 months |

| PE6 | Male | 27 | Single | Late | Postgraduate | 15 months | 10 months |

| PE7 | Male | 29 | Single | Early | Graduate | 18 months | 11 months |

| PE8 | Male | 27 | Single | Early | Graduate | 18 months | 10 months |

| PE9 | Female | 30 | Single | Late | Postgraduate | 18 months | 8 months |

| PE10 | Female | 30 | Married | Late | Postgraduate | 28 months | 6 months |

| PE11 | Female | 25 | Single | Late | Graduate | 15 months | 6 months |

| PE12 | Male | 34 | Married | Night | Postgraduate | 14 months | 8 months |

The semi-structured interview technique was used, to probe the process of initiation and incorporation of novice nurses in emergency bays, identifying their difficulties, needs, and proposals for improvement in the current induction plan. Observations, thoughts, and questions were recorded in a field diary and the information was then systematised and analysed thematically.5,20,23

Twelve interviews were conducted, with an average duration of 70 min, recorded and transcribed ad verbatim, with the prior written consent of the participants, whose names have been anonymised and replaced by pseudonyms.20,23

In accordance with the literature on the needs of the novice nurse, an interview script was developed consisting of an introduction, a framework and guiding, starting, and thematic questions: (1) What was it like for you to start working in an emergency department; (2) what feelings and emotions did you experience; (3) have you had difficulties in the adaptation process? (4) What knowledge do you think a nurse should have to perform a good physical examination in the context of critical and emergency patients? (5) Could you explain what knowledge an emergency bay nurse should have? (6) Have you experienced stressful situations or situations that you did not know how to solve? Tell me about those moments.

It is important to mention that the interview is based on a guide; however, the interviewer was free to include questions to probe the information.

The interviews were conducted in the emergency department in a personal and private manner in the doctor's office, outside the working day of each respondent, so as not to interfere with their activities. A tape recorder and a field diary were used during the interviews – with the consent of the respondents – in which the researcher recorded the most relevant aspects of the respondents' non-verbal language. To respect the scientific rigour of qualitative research, each interview was transcribed verbatim, thus fulfilling the conformability criterion. Finally, the interviews were presented to the respondents for approval, following the principles of transferability and credibility.

As an adjuvant tool, a photograph of the emergency bays was used, showing the different stretchers and equipment, without the presence of any patient or professional. The photograph was shown to the respondents during the interviews to elicit emotions and memories.

Data analysisA phenomenological analysis of the nurses' experiences was conducted based on the information collected in the field diary and their narratives, where the aim was to reflect the overall meaning of the text using interpretative, symbolic, and semantic elements.

Once the interviews had been transcribed, they were read line by line until patterns that stood out in the text were identified. A conceptual map was then used to organise and relate the key words, using open and selective coding to analyse the information. The interviews were coded for analysis, identifying themes and patterns, comparing possible variations, and establishing relationships between codes. Finally, this selective coding allowed the integration of the concepts around a category, obtaining the foundations and the initial structure to build a theory.

The technique of content analysis allowed us to identify, select, and analyse the concepts that emerged in the texts of the interview transcripts. It is an appropriate approach in qualitative methodology to evaluate the content produced during the interviews to identify patterns and common elements of the texts, and to identify, interpret, and understand the underlying meanings that the subjects gave to their lived experience.

The results were triangulated using the different techniques, with the aim of validating the information and detecting elements of contradiction that would allow us to open up spaces for discussion. Nvivo10 software was used for data analysis.

Ethical considerationsThe study was authorised by the ethics committee of the hospital where it was conducted (Reg. HCB/2021/1322). All persons who participated in the research had been previously informed and asked to collaborate voluntarily, and were explained the characteristics and objectives of the research, by means of the information sheet and informed consent form.

The interviews were anonymous, and identification was anonymised to guarantee data protection in accordance with Organic Law 3/2018 of 5 December.24 The study complies with the ethical principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki on medical research on human subjects25 and with the Code of Nursing Ethics.26

ResultsA total of 12 interviews were conducted with nurses from the emergency bays, based on an equal sample between men (6 participants) and women (6 participants) and between the different work shifts (4 professionals from each shift), with a mean age of 28.4 years (28.2 for men and 28.7 for women), with a standard deviation of 2.9. A total of 58.3% had a postgraduate degree and 41.7% a bachelor’s degree. The mean time worked in the emergency department was 17.1 months (standard deviation 4.9) and in the emergency bays it was 7.1 months (standard deviation 3.2). Four categories emerged as the main axes: (1) identification of shortcomings; (2) emotional dimension; (3) competencies of the expert nurse; and (4) needs detected and proposals for improvement.

Identification of shortcomingsInstitutional and organisational shortcomingsThe novice nurses highlight the importance of participating in a progressive induction plan for the first days of incorporation into the service, previous training and a good working environment being essential aspects to promote their self-confidence and security. However, their experience highlights the lack of a real and standardised induction plan. The guidelines for incorporation into the service are usually informal and with little gender perspective, with the consequent bias in the individual training of the professionals, reproducing the actions of more experienced and expert professionals, without a joint institutional strategy. “I don't feel that I was given an induction, either in terms of training or practically” (PE01). “[…] your learning depends on the colleagues you are with for the first few weeks, you end up repeating their actions, with their good and bad habits”. (PE04) "There is no joint or balanced training strategy". (PE07) "I really think that the ratio of male nurses who go down to the emergency bays is much higher than that of female nurses". (PE09)

The worst rated aspects in the emergency bays are the lack of interdisciplinary communication and the excess of professionals in the bays. The lack of organisation between the different professionals attending an emergency situation is a problem, relegating less experienced professionals and promoting a bad working environment, which directly affects the quality of care. "Too many people come down when a team goes on strike, it’s impossible to work well like that". (PE03) "[…] residents, nursing students, ambulance technicians, where practically nobody is doing anything, just watching and obstructing, and in the end, it’s the patient who’s most affected". (PE10)

Many of the difficulties experienced by new nurses are related to communication between nurses and the medical team, highlighting feelings of vulnerability based on hierarchical relationships: "The dynamic is based on doctors giving orders to nurses without taking each of the nurses’ roles into account". (PE09)

It emerges that novice nurses have to act according to the instructions of the more experienced nurses, who demand immediate, high-quality action, without considering the nurses' knowledge of the practice in question or giving them time to reason out their actions. In addition, medical professionals do not usually share the care plan with nurses, which often leads to great insecurity among novice nurses, which in turn underpins the lack of empowerment of the profession. "Nurses don't believe in our importance in an ICU or resuscitation bay, and if we believed it more, we would lead in more things". (PE04) "[Doctors] are often reluctant to listen and value our opinion". (PE11)

However, the importance and satisfaction derived from working among functioning teams is highlighted, bringing serenity, greater autonomy, continuous learning, and better adrenaline management: "You really feel very fulfilled when you feel supported by your colleagues, working in a coordinated and efficient way". (PE09) "It’s amazing how adrenaline is managed in these situations and the great autonomy we have as professionals". (PE10)

Some of the difficulties that the novice nurse experiences in the induction process is the feeling of not knowing what is being done and the difficulty of starting to work in a team without sufficient communication tools, as the following quotes indicate: "I had the feeling that I was far from well prepared to care for this type of patient and that I could be a danger". (PE07) "I constantly have the feeling that I don't know what I am doing". (PE04) "Communication between the team in complex situations… I think this is what most of us struggle with the most". (PE09) "No one has made sure that I have the level to react to critical situations… I am always afraid that at any moment a disaster could happen". (PE12)

In the emergency bays, the novice nurses act according to the instructions of the more experienced professionals, who demand immediate, high-quality action without considering the knowledge they have of the practice in question, or giving them time to reason their actions. In their narratives they argue an absence of stimulation of clinical and reflective judgement, thus furthering their sense of frustration and insecurity: "When we attend an arrest, we simply act following the indications of the expert nurses, without stopping to think about why we are acting". (PE06) "There is no encouragement at all to think about your actions… this creates a great sense of helplessness". (PE05)

Novice nurses express many feelings and emotions. From the nerves of starting to work in an unfamiliar environment, to the fear of being judged, abuse, or distress. This even leads them to define their workplace as "a battlefield" where there is constant tension. This tension is reflected in the field diary, where the shouting and demands of the more experienced nurses and doctors dominate: "Working in emergency bays, and even more so as a novice nurse, is like being on a battlefield". (PE02) "There are colleagues who become nervous under pressure and raise their voices or speak badly to you". (PE03)

This generates a great deal of stress and frustration among the more junior nurses: "Fear, frustration, stress…. I was frustrated to see that, for them, the things they were asking me were very obvious, and for me it was a total lack of knowledge". (PE06) "They told me that they didn't know how I’d been allowed into the bays, that I was a danger… ".

These situations lead to feelings of discouragement and insecurity, even to the point of questioning their own professionalism: "I became depressed at the beginning of my career". (PE01) "You get comments that can seriously affect the mental health of professionals who are starting out in the bays, making us feel that we are not valid". (PE05)

However, emotions interpreted in more negative terms, such as fear, nerves, and distress are also articulated with emotions seen as positive, such as interest and motivation: "Starting work in a resuscitation bay involves continuous stress mixed with motivation to help and vocation for the profession". (PE07)

Understanding professional competencies as the set of skills, knowledge, and aptitudes expected of an expert nurse, the most valued by novice nurses is the ability to know "what is going to be done and what is being looked for" from the moment the patient walks in the door: "In the critically ill patient it is important to know how to prioritise because otherwise you are lost"- (PE05)

To do this, it is necessary to "have tables, experience, and previous training" (PE07) and be very reflective: "A nurse working with these complex patients must be very reflective, and be agile in analysing what’s happening and what might happen". (PE10)

According to their narratives, expert nurses must be able to integrate technology into their patients' care, know how to apply reasoning and use effective, clear, and correct communication to work as a team. "An expert nurse must know how to handle devices and monitors, know how to reason their actions, and know how to communicate this to their colleagues correctly and clearly". (PE09)

With regard to the theoretical knowledge expressed, the expert professional must be up to date on the different emergency codes, master them, and know how to apply them in different contexts in a humanised way. It is also important for the most expert professionals to master and manage the most emotional part, and to manage communication strategies with the rest of the team. "You should use a calm voice to communicate, and not lose your temper". (PE03) "The leader should always make clear the message they want to give and to whom". (PE07)

A veteran nurse "must be trained in social skills, use positive reinforcement and take responsibility for the mental health of their team, knowing the limitations of each member". (PE08)

The narratives of the novice nurses highlight management of the ventilator and airway, the interpretation of arrhythmias, and teamwork as the greatest challenges in the process of adapting in emergency bays: "I would highlight the difficulty in handling technology and social skills". (PE08) "I found it very difficult to interpret the ventilator parameters and to learn to communicate correctly with the team". (PE09)

Among the proposals collected were the need to be able to go down to the emergency bays as an observer during the first month of adaptation to the service, to learn to view the patient holistically from a more relaxed perspective: "To have had the opportunity to go down before as an observer to take in the work dynamics". (PE01) "Being able to see real situations or in video format, even if only of expert nurses in action and doing their care work, would help a great deal to reduce stress". (PE11)

A proposal is made that this observation exercise be implemented through a virtual platform, with simulation cases by expert nurses and in the actual bays, to bring the real environment closer to novices. In addition, during the first weeks of adapting to the bays, a mentor figure from expert professionals is called for. "An expert colleague who, at the end of a complex case, asks you why things have been done one way or another, this would help a lot". (PE03)

The idea emerges of creating a programme not only to support novice nurses, but all professionals in their learning process, updating and standardising concepts, with regulated training and well-defined competencies. Among the most frequent proposals was to create a virtual technological support tool, adapted to the generational change, where it would be possible to consult recordings of interprofessional simulations where case resolution is done. At the same time, the idea was put forward of promoting clinical sessions given by nurses, in video format, where complex situations are presented and how they were resolved: "A platform where basic information on each subject can be consulted quickly and focused on nursing care". (PE02) "…] using virtual simulation. Avatars that simulate real and complex situations". (PE05) "…] virtual training adapted to our times… Paper is now a thing of the past and nobody reads long protocols". (PE09) "Presenting our experiences in clinical sessions would be an incredible recognition for our profession". (PE10)

The importance of implementing debriefing sessions in daily practice also emerged, in a scenario in which professionals report that this practice rarely or never takes place after a complex situation: "It would be nice if after every complex situation there was a kind of debriefing where colleagues could talk to each other about how they felt". (PE03) "The theory is very different from the practice… hospitals boast about the importance of debriefing and in reality, it is not done correctly or not done in most cases". (PE09)

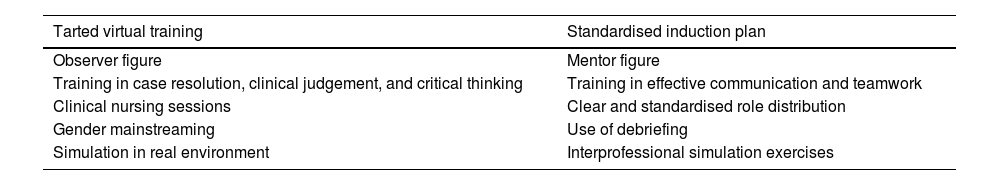

We have made a summary table with the aspects to be improved, to reinforce the impact and help the reader to consult the needs and proposals collected by the nurses (Table 2).

Proposals for improvement gathered.

| Tarted virtual training | Standardised induction plan |

|---|---|

| Observer figure | Mentor figure |

| Training in case resolution, clinical judgement, and critical thinking | Training in effective communication and teamwork |

| Clinical nursing sessions | Clear and standardised role distribution |

| Gender mainstreaming | Use of debriefing |

| Simulation in real environment | Interprofessional simulation exercises |

In the narratives analysed, the professionals flag up the inadequacy of the current induction plan, which is alien to the real needs of the group and far from fulfilling what they consider to be the 2 main axes: individual and collective training and the promotion of a good working environment. This is in line with previous contributions, which warned of this and highlighted the need to create standardised curricula, where more levels of support are offered, not only at a clinical level, but also in the social and emotional sphere.7,13,15 From the data presented, there is a mismatch between the positive experiences that novice nurses report having with their colleagues and the current lack of institutional organisation, indicating the need for a paradigm shift in the current organisational model.

In the analysis of the interviews and field diary entries, the most common feelings among novice nurses emerged as fear, insecurity, and stress. These negative feelings are somewhat related to those reported in the literature reviewed,2,12,15 where depression and anxiety are referred to as the main feelings. To cope with these situations, nurses emphasise the importance of learning to manage emotions, which has already been advocated by several precedents in terms of a direct relationship between emotional intelligence and job stability.3,12,15 Therefore, the data from the present study reflect the mental health risk presented by these professionals, coinciding with the high incidence of burnout syndrome in nurses reported by other authors.14,15

Among the aspects of greatest concern in emergency bays are the lack of interdisciplinary communication in complex situations and the difficulty for clinical and reflective judgement. No studies were found evaluating aspects of a service as specific as emergency bays. However, the most highly valued aspects were never feeling alone, gaining autonomy, and adrenaline management. Another highly valued item was communication between nurses, coinciding with other scientific contributions,15,16 which show the good strategies they undertake between them and the lack of teamwork skills of other specialties. In this sense, some contributors11,16,19 defend the need to implement teamwork dynamics led by nurses, offering communicative strategies to the other professionals to work in an interdisciplinary and efficient manner and in turn promoting the role of the nurse as a leader.

One of the topics most represented in the literature,8,9,14,15,18,19 and discussed in our study, is the need for innovative and targeted training programmes, in the work environment, to help integrate theory with practice and support nurses in their learning process. This is evidence to support the creation of multimodal, targeted, and innovative training programmes, where simulation is combined with the use of virtual platforms, using complex and contextualised simulation scenarios for emergent situations.

Another aspect to assess in the training programme, in line with other authors,10,12,13 would be the integration of social tools to facilitate communication between novice nurses and more experienced nurses, a skill which, according to the literature,16 is clear in nurses, but lacking in other specialties. The simulation of cases formed by an interprofessional team (doctors, nurses, care assistants, managers, etc.) would help to foster these interpersonal relationships, teamwork, and patient safety.

Linking the information gathered from our narratives with that of other authors8,14,18,19 we can extract the main pillars on which we should focus our training programmes: the integration of technology in care, clinical judgement in emergent situations, communication between professionals, the acquisition of skills, and decision-making. This support tool would also make it possible to implement clinical nursing sessions, a new paradigm already resonating in the current literature,17,18 and included in our study, in which complex situations and how they were resolved are presented. This represents a qualitative leap in our profession and in patient safety, as well as an advance in our practice, incorporating the use of scientific evidence and standardising of procedures.

In addition to the aforementioned simulation programmes, it is striking that debriefing (guided reflection) is little used as a tool for continuous improvement in our field of study. The current literature6 shows a substantial increase in the learning curve thanks to this practice, which also makes it possible to learn from mistakes together and improve communication and relationship skills among peers, as the respondents in our study agree. From the narratives analysed, the idea also emerges of integrating psychological interventions during debriefing sessions to encourage peer support, to avoid the symptoms of anxiety, stress, and insecurity expressed in the interviews conducted, which would also reduce job dissatisfaction and resignation, as stated in the current literature.11,14

The main limitations of this study are the difficulty of generalising the results outside the geographical and temporal context in which the research was conducted, and therefore, caution should be exercised in extrapolating the results obtained to all clinical professionals. Although our results seem to provide valid information to determine key aspects in the formative and emotional management of novice nurses, enlarging the sample in future research in other hospitals should serve to contribute to this object of study. At the same time, it is important to mention that due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many nurses with no previous experience were forced by the crisis itself to work in emergency bays. Some of these were included in the interviews, the context of the pandemic itself being considered a stressful component.

ConclusionsThe experiences reported by novice nurses warn that the complexity of working in emergency bays can exceed expectations and raise questions about whether one is sufficiently qualified or trained for the job. In this context, the process of learning and progressive adaptation of novice nurses has several shortcomings at institutional, organisational, and interdisciplinary levels. Elements such as the absence of induction plans, the lack of reasoning about actions that are taken, or the uncertainty about their role in the bays, make emergency intervention difficult and put the emotional health of nurses at stake.

The difficulty in developing clinical and reflective judgement, the high level of stress, the insufficient training, and the lack of interdisciplinary communication and teamwork skills suggest a real induction plan should be rethought, with specific training and support strategies to improve interventions in the emergency context, to protect the mental health of novice nurses and to ensure the integrity of patients. In this sense, there is a call to explore multimodal and immersive training projects, combining simulation with the use of virtual platforms, together with the implementation of tools such as debriefing and clinical nursing sessions, where more levels of support are offered, not only on a clinical level, but also in the social and emotional spheres.

FundingNo specific support from public sector agencies, commercial sector, or not-for-profit organisations was received for this research study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

We would like to thank the head of the emergency department of the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Gemma Gallardo Gonzalez, for her management model that encourages and helps nursing research, and for all her support in the present study.