To evaluate how nurses cope with the death of a paediatric patient, relate it to the different sociodemographic variables, and to describe personal coping strategies used by nurses in managing the process and accepting the death of the patient.

MethodologyAn observational, descriptive and cross-sectional study, carried out from January to June 2018 with nurses from the palliative care area, intensive care unit, neonatology and oncohaematology area of a tertiary paediatric hospital in Barcelona city. An ad hoc questionnaire was applied, divided into three parts: socio-demographic data, the Bugen Scale of coping with death and two open questions.

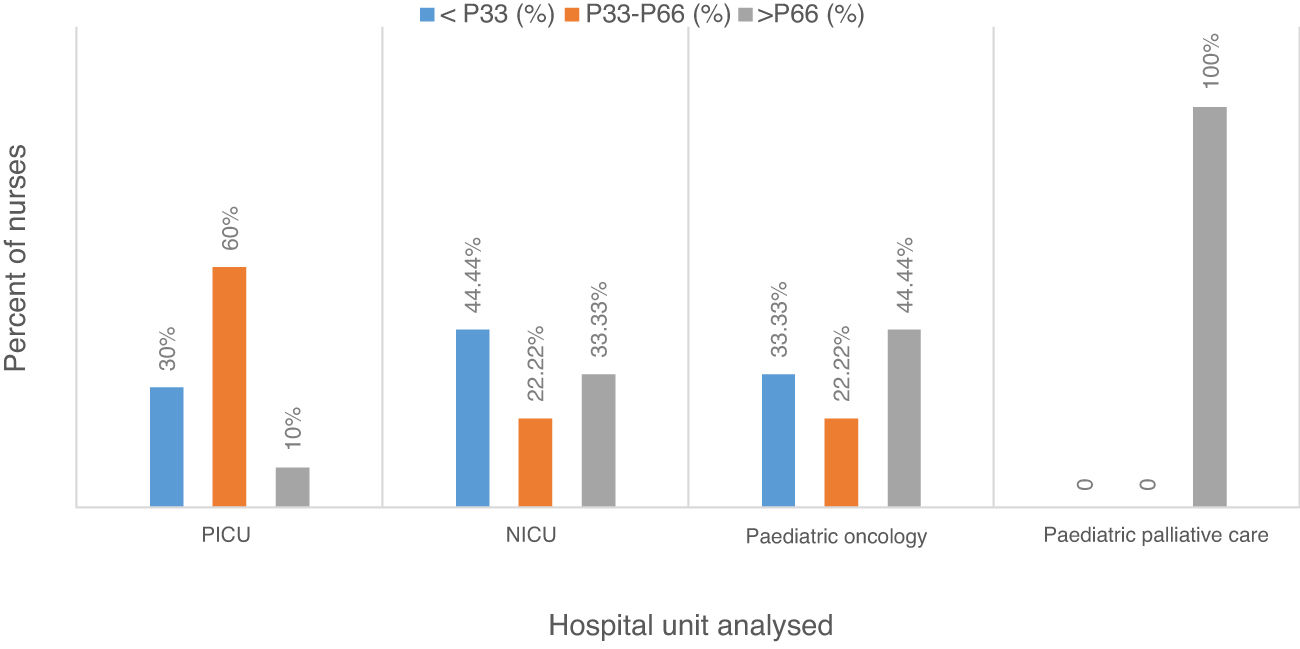

Results31.37% of the respondents faced the process of death of the paediatric patient adequately, while 33.33% did not cope well. The best coping was in paediatric palliative care, followed by paediatric oncohaematology, neonatology and, finally, the intensive care unit. In addition, the variables related to this coping are the work shift, the death of a loved one in less than 3 years and previous training. On the other hand, the age of the respondents, experience in the unit and having children are not related to coping. Moreover, the professionals surveyed demand more training to improve their coping in this area, as well as interdisciplinary sessions to discuss cases of deceased patients.

Evaluar el afrontamiento ante la muerte de un paciente pediátrico que realizan las enfermeras, relacionarlo con las diferentes variables sociodemográficas y describir las estrategias de afrontamiento personal que utilizan estos profesionales para manejar el proceso y aceptar la muerte del paciente.

MétodoEstudio observacional, descriptivo, correlacional y transversal, realizado de enero a junio de 2018 con enfermeras de las áreas de cuidados paliativos pediátricos, Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos Pediátricos, Neonatología y Oncohematología de un hospital pediátrico de tercer nivel asistencial de la ciudad de Barcelona. Se administró un cuestionario ad hoc dividido en tres partes: datos sociodemográficos, escala de Bugen de afrontamiento a la muerte y dos preguntas abiertas.

ResultadosEl 31,37% de los encuestados afronta el proceso de muerte del paciente pediátrico de forma adecuada, mientras que el 33,33% tiene un mal afrontamiento. El mejor afrontamiento se obtuvo en cuidados paliativos pediátricos, seguido de oncología pediátrica, neonatología y, por último, cuidados intensivos. Además, las variables relacionadas con este afrontamiento son el turno de trabajo, la muerte de un ser querido en menos de tres años y la formación previa. Por el contrario, la edad, la experiencia y los hijos no se relacionan con el afrontamiento. Los profesionales encuestados demandan una mayor formación sobre esta temática para mejorar su afrontamiento y la necesidad de contar en el ámbito de trabajo con un apoyo psicológico profesional.

The literature consulted described how nurses find themselves in close contact with death and the process of a patient’s death. Studies present an analysis of the feelings and attitudes of nurses in these situations.

What does this paper contribute?This article provides a description of how nurses cope with the death of a paediatric patient, differentiating according to the hospital unit in which they work. In addition, it details the coping mechanisms used by these professionals and the need to receive more specific, in-depth training in this matter that the male and female nurses perceive.

Upon analysing different units, the differences in coping can be observed. This makes it possible to institute improvements for the female and male nurses with respect to coping with the death of a paediatric patient. Such measures could include training and case closure sessions.

IntroductionThe social and cultural context of a person has an impact on coping with the death of a patient, insofar as society creates a shared reality arising from its values, beliefs and standards.1,2 In addition, we must add the fact that society considers death a threatening, strange process that is surrounded by strong fears. This is why an individual reacts with fear and anxiety when facing death.3

This conceptual idea of the process of death that exists in society is reflected in the healthcare world, among which we find the paediatric context. The increased survival of these patients has led to a change in the concept of child mortality, currently associating it with that of underdeveloped societies and the elderly.3

Another consideration is that the development of nursing knowledge has taken place within the health sciences. However, the close contact with the patient and the family cause the daily practice of nursing to be imbued with historical context, social beliefs and personal experiences. This lends a subjective part to a nurse’s day-by-day work stemming from the socially constructed meanings. Consequently, the permeations of society and the personal experiences of each nurse are reflected in his or her actions and how the individual acts towards the patient in the process of death.4,5

Likewise, during the history of the health sciences, the objective has been focused on resolving the threats that put the life of the patient at risk; it is considered a success if the patient survives and a failure if the patient does not.6,7 Consequently, the professionals are educated to take care of the patients with the goal of maintaining health and life.7 Death is not accepted as a natural occurrence and the healthcare professional receives little training on coping with patient death and on the communication and relationship skills needed to deal with these patients. This lack of preparation and training in these skills can increase the levels of stress in the professional.8–10

The contact with and the attention of the nurse to the death of a patient represents a very emotional, impactful experience. It is one of the most stressful occurrences due to the contact with someone else’s pain, the feeling of loss, the suffering of the patients and their death.1,2,11,12 The other important factor involved that creates higher levels of anxiety for the nurses, because of the factors mentioned before, is that the patient is a child.3,13

The feelings and emotions that the nurses show most frequently are related with emotional fatigue; they are expressed with anguish, frustration, guilt, desperation, resignation, sadness and deception.9,13–18 In some cases, the death of a patient can be experienced as failure in the nurse’s actions and the therapeutic efforts to save the patient’s life, which can lead to feeling of professional failure and, consequently, of impotence.5,16 Likewise, these occurrences generate fear and impotence due to the fear of the unknown and to the impossibility of controlling the situation.16,19

According to the theory of Cumplido Corbacho and Molina Venegas,20 when people find themselves in a context in which the situation exceeds the resources that they have available and their personal well-being is put in danger, they take cognitive and behavioural steps to reduce and handle the internal and/or external demands. That is, in the face of the stressful situation, people evaluate the situation and their own skills for coping with it, which will be what give rise to stress reactions. Based on these reactions, coping mechanisms arise. Consequently, coping is understood to be the behavioural and/or cognitive actions that help to face the stressful situations. All this means that, faced with the situation of the death of a paediatric patient, the professional searches for coping mechanisms to reduce the intensity of the feelings that this process of death generates and make those feelings more tolerable.15,21 To accomplish this, 2 types of mechanisms can be used: maladaptive, using resources that are ineffective in reducing the stress, and adaptive mechanisms, those in which protective strategies are marshalled.21 A study carried out in Colombia indicated that nurses principally used maladaptive strategies aimed at inhibiting their feelings in front of the patient and family, although favouring comforting to relieve suffering.22

This study has arisen from all of what has been indicated. Our general objective was to describe how nurses cope with the process of the death of a paediatric patient. The specific objectives stemming from this were: (1) evaluating the level of coping the nurses achieve when faced with the death of a paediatric patient; (2) analysing the nurses’ coping with deaths of paediatric patients and the various sociodemographic variables of the nurses; and (3) describing the main coping strategies that these professionals use to handle the process and accept the death of the patient.

This study has been structured following the recommendations of the Declaration of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) initiative.23

Materials and methodThis was an observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study, from January to June 2018, in which we included the nurses forming part of the areas of Paediatric Palliative Care (PPC), Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU), Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) and oncology and haematology service at a tertiary paediatric hospital in the city of Barcelona (Spain).

The study population consisted of 149 nurses that worked in those units/services, distributed as follows: 4 PPC, 45 PICU, 80 NICU and 20 oncology and haematology. The study participants were selected using a non-probabilistic and intentional sampling, given that the professionals were offered the possibility of participating in the study and voluntarily decided if they wished to do so. We included professionals with an age of 25 years or older, who signed an informed consent; nurses with less than 2 years of experience working at the hospital were excluded.

The sociodemographic variables recorded were as follows: age, sex, years worked, work shift, number of children, the death or not of a loved one in the last 3 years and previous studies about coping with death. The result variable corresponded to the level of coping achieved by the professionals analysed.

To study this degree of coping, we used an ad hoc survey created with Adobe Acrobat Pro DC® that consisted of 3 blocks: sociodemographic variables, the Bugen Coping with Death Scale, and 2 open questions to answer: 1) What strategies do you use to cope with the death of a patient? and 2) What resources do you believe would be adequate for helping you to cope with patient death?

It is important to mention that the main measurement tool in the study, the Bugen Coping with Death Scale, has been adapted to Spanish by Schmidt Río-Valle,24 and has shown adequate measurement properties of validity and reliability (internal consistence determined by Cronbach coefficient of 0.824). In addition, the adapted scale was validated in 2017 for palliative care professionals.25 The scale is composed of items that investigate the skills and capacities for coping with death, as well as beliefs and attitudes towards it. There are 30 items with a Likert-type evaluation scale from 1 to 7, in which 1 represents not agreeing at all with the statement and 7, being completely in agreement. The final score is computed by inverting the value of Items 13 and 24 and adding up all the scores. A score lower than the 33rd percentile (P33) indicates poor coping, while a score above the 66th percentile (P66) corresponds to good coping.

The data gathering procedure lasted for a month and consisted of 3 phases. In the first phase, information was given about the study, informed consents were signed, and the participants were told that they would receive the survey via email. The second phase consisted of receiving the completed 3 blocks of the ad hoc survey online and compiling the answers. The third phase took place 2 weeks after the beginning of the study and consisted of a reminder about the study, through both email and on-site, for all the professionals, especially those that forgot and had indicated that they wanted to answer the survey.

Statistical analysisThe data were analysed using the statistical programme RStudio®. The quantitative variables were described with the mean, standard deviation, median or interquartile range, as appropriate. The categorical variables were described using frequencies (n) and percent (%). The scores obtained on the Bugen Scale were compared among the independent variables with the Student t-test or the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U, according to distribution. In addition, depending on the type of variable, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used with the Benferroni test as a post hoc test.

As for the 2 open questions, a thematic analysis was performed on them. The answers were coded into similar ideas or categories and interrelationships among them were sought.

The data were considered statistically significant if the P value was ≤0.05.

Ethical considerationsDuring the entire process, the ethical principles reflected in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Belmont Report were followed. The Committee of Ethics and Clinical Research at the centre where the study was carried out also certified the study. Once certification had been obtained, the possible participants were informed about the objectives of our research, and verbal and written informed consent for free and voluntary participation was given.

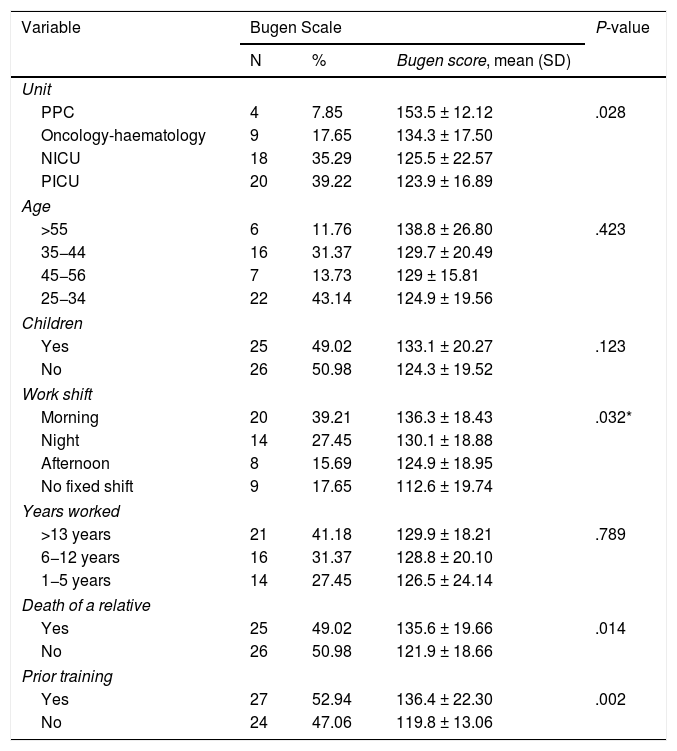

ResultsThe rate of response in the study was 34.23%; of the total of 149 male and female nurses given the survey, 51 completed and returned it. Classifying by hospital service/unit, there were 4 professionals that worked in PPC (7.85%), 20 in PICU (39.22%), 18 in NICU (35.29%) and 9 in oncology and haematology (17.65%). Out of the total nurses that could answer from each service, 100% of the nurses in PPC responded, 45% in paediatric oncology, 44.44% in PICU and, lastly, 22.5% in NICU (Table 1).

Statistical analysis of the Bugen Scale and the sociodemographic variables.

| Variable | Bugen Scale | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | Bugen score, mean (SD) | ||

| Unit | ||||

| PPC | 4 | 7.85 | 153.5 ± 12.12 | .028 |

| Oncology-haematology | 9 | 17.65 | 134.3 ± 17.50 | |

| NICU | 18 | 35.29 | 125.5 ± 22.57 | |

| PICU | 20 | 39.22 | 123.9 ± 16.89 | |

| Age | ||||

| >55 | 6 | 11.76 | 138.8 ± 26.80 | .423 |

| 35−44 | 16 | 31.37 | 129.7 ± 20.49 | |

| 45−56 | 7 | 13.73 | 129 ± 15.81 | |

| 25−34 | 22 | 43.14 | 124.9 ± 19.56 | |

| Children | ||||

| Yes | 25 | 49.02 | 133.1 ± 20.27 | .123 |

| No | 26 | 50.98 | 124.3 ± 19.52 | |

| Work shift | ||||

| Morning | 20 | 39.21 | 136.3 ± 18.43 | .032* |

| Night | 14 | 27.45 | 130.1 ± 18.88 | |

| Afternoon | 8 | 15.69 | 124.9 ± 18.95 | |

| No fixed shift | 9 | 17.65 | 112.6 ± 19.74 | |

| Years worked | ||||

| >13 years | 21 | 41.18 | 129.9 ± 18.21 | .789 |

| 6−12 years | 16 | 31.37 | 128.8 ± 20.10 | |

| 1−5 years | 14 | 27.45 | 126.5 ± 24.14 | |

| Death of a relative | ||||

| Yes | 25 | 49.02 | 135.6 ± 19.66 | .014 |

| No | 26 | 50.98 | 121.9 ± 18.66 | |

| Prior training | ||||

| Yes | 27 | 52.94 | 136.4 ± 22.30 | .002 |

| No | 24 | 47.06 | 119.8 ± 13.06 | |

NICU: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit; PICU: Paediatric Intensive Care Unit; PPC: Paediatric Palliative Care; SD: standard deviation.

Of the professionals returning surveys, 4 were men (7.84%) and 47 were women (92.16%). The mean age of those surveyed was 38.19 ± 10.21 years; 50.98% (n = 26) did not have any children. As for age, 43.14% (n = 22) of the study sample were in the range of 25–34 years old, followed by 29.41% (n = 16) that were between 35 and 44 years old, 15.69% (n = 7) fell in the range of 45–54 years old and 11.76% (n = 6) were older than 55 years old. Of those collaborating, 39.21% (n = 20) worked the morning shift, and 41.18% (n = 21) had more than 13 years of work experience (Table 1).

The mean score obtained on the Bugen Coping Scale was 128.63 ± 20.18 points (the maximum points for the Scale were 210). Analysing the means of the different services, there were statistically significant differences between them (P = .028, Table 1). Afterwards, PPC was compared with the rest of the services, given that it was the one that presented the highest mean. Statistically significant differences were also seen with respect to coping with the death of a paediatric patient (P = .081).

An analysis by percentiles revealed that the P33 obtained in the sample was located at 121.48 points, while the P66 corresponded to 135 points. A total of 17 professionals (33.33%) were below P33, indicating poor coping with death; 16 nurses (31.37%) were above P66, indicating that they coped with the process of death adequately. Analysing these percentiles differentiating among the 4 services, it was found that 100% (n = 4) of the professionals in PPC coped well in the face of the death of a patient; in contrast, 10% (n = 2) in PICU, 33.33% (n = 6) in NICU and 44.44% (n = 4) in oncology and haematology coped well (Fig. 1).

The scores obtained were analysed by age groups as follows: 25–34, 35–44, 45–54 and >55 years old (Table 1). No statistical significance was obtained (P = .423) upon comparing the groups, so age is not a variable related with coping with death. These age groups were also compared with percentiles 33 and 66 and, again, no statistical significance was found. There were no statistically significant differences between the professionals that had children and those that did not (P = .123, Table 1).

The Bugen Scale results were analysed differentiating between the various work contracts (permanent staff and intermittent), finding statistically significant differences in the means of the total score (Table 1). The mean scores on the Bugen Coping Scale for the nurses that had a permanent shift (regardless of which shift it was) were higher than the means of those that had a varying shift. A statistically significant difference was found between the 2 groups (P = .032).

The mean of years worked was 12.31 ± 9.82 years for the total study sample. The following classification was used for the analysis, differentiating according to years of work experience26: low = 1–5 years, medium = 6–12 years, and high ≥13 years. No statistical significance was obtained (P = .7894) based on time worked.

A statistically significant relationship was observed between the professionals that had suffered the loss of a relative in the last 3 years and those that had not (P = .014). For that reason, we focused on that analysis, evaluating Item 21 on the Bugen Scale («I feel capable of handling the death of others close to me»). It was found that the mean score for this item was 4.52 ± 1.39 points for those that had suffered the death of a relative, versus 3.31 ± 1.64 for those that had not. This correlates with better coping in the first group.

As for prior training in the matter of coping with death, a total of 27 professionals surveyed (52.94%) indicated that they had received such training. The mean of those that had training was higher than those that had not (136.4 ± 22.3 versus 129.8 ± 13.1 points), with statistical significance (P = .002, Table 1).

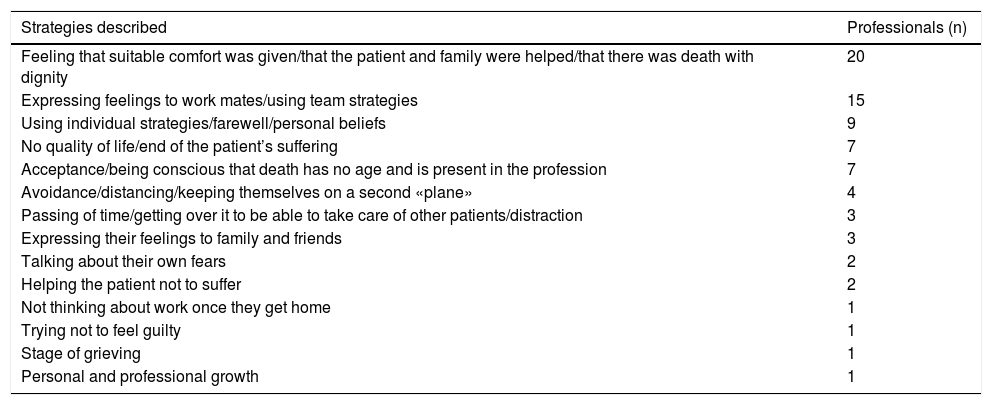

Turning to the open questions, 39.22% of those surveyed (n = 20) said that, to accept the death of a child, it helped them to feel that they had accompanied them with dignity during the process, preventing the suffering of the patients and offering them with best care possible. In addition, 29.41% (n = 15) mentioned that talking with their work colleagues helped them to be able to express their feelings openly (Table 2).

Coping strategies used by the nurses (n = 51 professionals*).

| Strategies described | Professionals (n) |

|---|---|

| Feeling that suitable comfort was given/that the patient and family were helped/that there was death with dignity | 20 |

| Expressing feelings to work mates/using team strategies | 15 |

| Using individual strategies/farewell/personal beliefs | 9 |

| No quality of life/end of the patient’s suffering | 7 |

| Acceptance/being conscious that death has no age and is present in the profession | 7 |

| Avoidance/distancing/keeping themselves on a second «plane» | 4 |

| Passing of time/getting over it to be able to take care of other patients/distraction | 3 |

| Expressing their feelings to family and friends | 3 |

| Talking about their own fears | 2 |

| Helping the patient not to suffer | 2 |

| Not thinking about work once they get home | 1 |

| Trying not to feel guilty | 1 |

| Stage of grieving | 1 |

| Personal and professional growth | 1 |

Finally, we explored the proposals that the participants made for improving the processes of comforting during the grieving process and coping with death. It was observed that 25.49% (n = 13) of the nurses indicated the need to carry out therapies with an interdisciplinary team to have a space where they could talk about their feelings and emotions that arose from the death of a patient. In addition, 17.65% (n = 9) of the nurses believed that being able to contact a psychologist from the centre to handle their feelings would also be helpful. Lastly, 27.45% (n = 14) expressed their wish to receive more training in this matter, so as to have more tools and coping strategies available.

DiscussionThe results of our study make it possible to objectify that, of the participating professionals, 33.33% cope poorly with the death of a patient, while 31.37% cope with the process of the death adequately. More specifically, the best coping occurs in the PPC unit, given that 100% of those surveyed obtained good coping results. Paediatric oncology and haematology come second in the ranking, with 44.44% of the professionals achieving good coping, while NICU follow with 33.33% and, lastly, PICU with 10%. The better coping shown by those in the PPC of the hospital analysed could be related to the continuous education on death and the process of death that takes place, as well as the interdisciplinary sessions to discuss the cases of patients that died.

In this study, the average of total points of those surveyed on the Bugen Scale is similar to that of another study that used the same instrument26 (128.66 points in our study versus 129.33 points in the study mentioned). Nevertheless, in our study the percent of professionals with poor coping was lower (33.33% versus 37%, respectively).

The age of the nurses surveyed is not a variable that conditions coping with patient death in this research, which coincides with another 2 studies.2,4 We have found articles that state that there is a relationship between work experience and coping with the death of a patient,4,12,13 as well as a greater likelihood of burnout syndrome.27 Even so, we have not found a relationship between work experience and coping, a fact that coincides with the results given in another article.8 This discrepancy about coping, based on work experience, could be due to the type of coping that occurs in the face of death; that is, whether the coping is adaptive or maladaptive.

With respect to the 2 variables of age and work experience, there is a discrepancy about their relationship with coping with the death of a patient. For that reason, there should be more in-depth research about the issue, which combines both quantitative methodology (to evaluate coping with death) and qualitative methodology (to analyse the coping strategies that the individuals use).

In spite of the results of the present study, 4 articles state that the nurses see their children and/or grandchildren reflected in the patients. This is a fact that leads to more anxiety and suffering.3,18,28

According to the literature, work shift affects coping: working shifts generates greater emotional fatigue or burnout syndrome27 and working the morning shift reflects a greater emotional expression.29 These conclusions agree with the results obtained in the present study, in which the professionals without a fixed work shift cope negatively with the death of a patient. This may be due to the fact that changes in the work shift can interfere with neurophysiological and circadian rhythms and/or involve social isolation, given that varying shifts make it difficult to maintain social and family life.29 Further research is needed to evaluate coping based on shifts to ascertain whether working with varying shifts increases emotional fatigue, as current literature suggests.

The experience of the death of someone close in the last 3 years leads to better coping in the nurses.4 In spite of this, there are 2 articles in which it is stated that this causes greater difficulty in controlling emotions.11,30

The lack of training is widely documented in the literature as a triggering factor in poor management of the process of death.1–4,11,12,21,26,31 For that reason, educational programmes should be part of both undergraduate studies and continuous education, to improve patient healthcare and ensure the physical and psychosocial integrity of the professionals.21,32 The best educational intervention that professionals can receive to improve their personal skills should therefore be investigated.

Coinciding with the adaptive strategies described in the literature for coping with the death of a patient,21,33 the strategy most used by the participating professionals is self-confidence; that is, feeling that they have accompanied the patient with dignity in the process of death. Another very used adaptive resource is expressing feelings with a multidisciplinary team.6,13,14,21,34,35 It might be of interest to have sessions in which to discuss the cases of patients that died,30,34 such as those carried out periodically in the PPC service in the hospital in which the present study was performed.

Some of the nurses state that accepting death as a natural part of life, that does not depend on the age of the patient, and that is a natural element of their work setting helps them to cope with it.13,21,33 Likewise, they seek a meaning for death, thinking that the patient would not have had a life of quality and that it keeps them from suffering more from their illness.1,14 In a different vein, the death of a patient is harder to assimilate if it is sudden.33 As our results confirm, only 10% of the professionals working in the PICU have good coping. This could be related to sudden patient death, because it is the unit in which the most cases are produced.

In contrast, the present study reveals a strategy considered to be one of the most maladaptive in coping with the death of a patient: emotional detachment from the situation.1,4,13,18,21,34 Because of the feelings of anxiety and insecurity that the professional may experience, this detachment serves as an attempt to separate oneself from pain and suffering. This avoidance behaviour generates a non-confronted grief that can undermine the professional’s work capabilities.14

Those surveyed indicated the need to be able to count on professional psychological support in the work setting,1,19,28,33,36 in order to minimise the impact that the death of a patient can cause.28 There was just 1 article in which the professionals surveyed had a support psychiatrist available and, coincidently, they were the only ones that indicated that they enjoyed the relationships with those patients and their families.35 It would be of interest to analyse, in a hospital setting, the role of a psychologist specifically trained in coping with death and the grieving process, to which the professionals could turn if needed. It would also be beneficial to carry out a study on beginning to institute case sessions with an interdisciplinary team, analysing whether there is a positive effect on the professionals and on their coping in the face of the death of a paediatric patient.

The limited sample of the present study is its main limitation. In addition, there is quantitative inequality between the units analysed, which makes it difficult to compare them. Likewise, the results of this study are not transferable to other hospitals. To deal with both these issues, there could be future multicentre studies with various paediatric hospitals that have the clinical units that we analysed available. For an in-depth analysis of both the resources that the professionals have available and those that would help them to improve their handling of these situations, a qualitative study is needed in which the method of data collection would be detailed interviews with the nurses.

The results of the present research makes it possible to conclude that the paediatric palliative care unit copes better with the death of a patient. This might be related to the continuous education in place on death and the process of death, as well as their interdisciplinary sessions to discuss the cases of patients that died. The offer in specific training on this issues should therefore be increased and case sessions with the interdisciplinary team that takes care of the patient should be established.

In the hospital setting, coping with the death of a paediatric patient has to be improved. It would be beneficial to carry out a detailed analysis of the role of a psychologist to which the professionals could turn if needed, a psychologist specifically trained in this issue and in the process of grieving.

Commenting on the variables analysed, age and experience in the unit/service are not related to coping with the death of a patient. In contrast, in the literature previously mentioned, they are indeed related. Consequently, research to analyse this is needed, studies that combine both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. In addition, shift work does impact coping with patient death, showing worse levels in professionals that vary shifts. This should be studied in greater depth to objectivise whether worse coping may be due to greater emotional fatigue, as current literature suggests.

FundingThis project has not received any type of funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We wish to express our gratitude to the nurses at the Hospital Sant Joan de Déu for their participation in the study, without any financial gain, given that the study could not have been carried out without their collaboration.

Please cite this article as: Lledó-Morera À, Bosch-Alcaraz A. Análisis del afrontamiento de la enfermera frente a la muerte de un paciente pediátrico. Enferm Intensiva. 2021;32:117–124.