To determine the level of readiness of the healthcare team regarding family participation in the care of the critically ill adult and their relationship with the individual characteristics of the participants in a medical-surgical intensive care unit (ICU) in Santiago de Chile.

MethodA cross-sectional correlational study using a quantitative method and including a focus group to explore the perception of healthcare staff of family participation in the care of the critically ill patient.

ResultsThe level of readiness of the healthcare team for family participation in the care of the critically ill patient is medium, at 13.81 out of a total 20. The greater the readiness, the lower the age (r = −0.215; P = 0.019), the higher the rating of previous experience working with families (r = 0.304; P = 0.006), and the higher the perception of being comfortable with different activities in the care of the critical patient (r = 0.495: P < 0.001). The participants also state that the work environment of the unit, the patient's condition, the relatives’ characteristics, personal judgement, and the preparedness of relatives affect their readiness.

ConclusionsThe results contribute towards determining the healthcare team's level of readiness in a setting where the subject of the study has not been implemented. The readiness of the healthcare team is medium, and is related to individual characteristics of the healthcare staff, and to organizational and family aspects. Therefore, strategies are required to address these aspects that might increase readiness.

Identificar el nivel de disposición (readiness) del equipo de salud frente a la participación familiar en el cuidado del paciente crítico adulto y su relación con las características individuales de los participantes, en una unidad de paciente crítico (UCI) médico-quirúrgica de Santiago de Chile.

MétodoEstudio correlacional de corte transversal que utiliza un método cuantitativo e incorpora un grupo focal para profundizar en la percepción del personal de salud respecto a la participación familiar en el cuidado del paciente crítico.

ResultadosEl nivel de readiness (disposición) del equipo de salud frente la participación familiar en el cuidado del paciente crítico es medio, siendo 13,81 puntos de un total de 20. A mayor nivel de disposición menor edad (r = −0,215; p = 0,019), mejor calificación de la experiencia previa de trabajo con familias (r = 0,304; p = 0,006) y mayor percepción de comodidad frente a diferentes actividades del cuidado del paciente crítico (r = 0,495; p < 0,001). Los participantes afirman además que el contexto laboral de la unidad, la condición del paciente, las características de los familiares, el criterio personal y la preparación del familiar afectan su nivel de disposición.

ConclusionesLos resultados aportan al conocimiento de la disposición (readiness) del equipo de salud en un contexto donde la temática no se ha implementado. El nivel de disposición del equipo de salud es medio; se relaciona con algunas características individuales del personal de salud, así como con aspectos organizacionales y familiares, de modo que se requieren estrategias que aborden estos aspectos y así el nivel de disposición podría aumentar.

What is known

Family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient is an issue that brings benefits for the patient, the family and the healthcare staff. The healthcare team reaffirms the latter, but do report a series of barriers and facilitators in units where this practice has been carried out.

What it contributes

The contribution of this study was to increase knowledge regarding the individual characteristics of health personnel associated with their willingness to incorporate the family into patient care activities in a unit where this would be an innovation.

Study implications

Among the main implications of this study is the modification of clinical practice towards humanised practices centred on the patient and their family. It provides knowledge that will allow the institution to generate strategies that consider the willingness of professionals to implement the change, and in turn, gives rise to new research that addresses family participation as one of the central axes of care.

In the early 20th century, intensive care or critical patient units (ICUs) isolated patients from their families as this was thought to have a negative impact on their recovery.1 However, over the years, efforts have been made to make these units more accessible to the family, as evidence supports the importance of the patient-family bond for patient recovery.2–4

To achieve this, the family-centred care approach emerged at the beginning of this century.5 It seeks to promote the strengths of the patient and their family to improve their care, using education as the main tool.3 It recognises that both patients and their families are essential allies for the quality and safety of care, which translates into better health outcomes, better patient and family care experience, greater satisfaction of clinical staff and better use of resources.1 Specifically, family participation in the care of the critically ill patient (family involvement), as part of the family-centred care approach, refers to “the active interaction between healthcare professionals and patients and their families”.6 Under this perspective, the family is involved in a voluntary, progressive and directed manner, with the help of the professional, in the care of the patient.1

Evidence reports that family participation in the care of the critically ill patient is fundamental in the management of stress and family anxiety generated by the hospitalisation of a loved one in a unit of such complexity.2,3 It also facilitates closeness and communication between the parties involved.4 Last but not least, it allows the professional to get to know the patient holistically and thus provide better care.3

Family involvement has also been addressed as a topic by the North American Intensive Care Society,7 which recommends family involvement in its clinical guidelines, mainly in the neonatal context. In fact, an important role of the paediatric intensive care nurse internationally is to encourage parents to be involved in the care of their children,8 as they are recognised as key players in the patient's recovery.9 However, in the adult context, implementation of family involvement has been scarce. In fact, the literature reports a number of barriers perceived by the health care team to family involvement. Some of these include the need to protect privacy, lack of time to train family members and high workload, as well as their perception that the family may be afraid of harming the patient.10–14 While there are recommendations regarding the relevance of this issue in the context of the critically ill patient, the literature shows difficulties in its implementation in adult patients. Because of this, the adoption of active family involvement in patient care has rarely been reported internationally and has not been reported nationally. In an adult context therefore, they are considered innovative interventions.

From an innovation perspective, in order to measure the effectiveness of its implementation, the concept of “readiness”15 has emerged. This has been interpreted by various authors and defined as readiness for change,16,17 given that it defines the extent to which an individual believes that a change is necessary and has the capacity to implement it.17 There are two approaches, individual and organisational; the latter, unlike the individual, refers to the belief in the collective ability to make a change because they share the resolve to implement it.18,19 The concept of readiness covers 5 main areas: motivation, perceived need, staff attributes, organisational climate and institutional resources. Institucionales.20 Health team motivation is defined as a perceived need and pressure for change. In this case, motivation to adopt family involvement in the care of adult critically ill patients is perceived as being flexible to make changes. With regard to personal attributes, it refers to efficacy, influence and adaptation. In terms of organisational climate, it includes the perception of clarity of mission, cohesion, communication and openness to change. Finally, institutional resources include both physical resources and training.20,21

Thus, Weiner19 states that “readiness” is a predictor for the successful implementation of change. If this concept is taken to the context of family involvement, the greater the willingness of the healthcare team to involve the family in the care of the critically ill patient, the greater the probability of success in implementing this innovation in an ICU. Along these lines, international evidence, although it does not specifically refer to “readiness”, shows that healthcare teams with a more positive perception of the issue involve family members more actively in patient care.22 In this study, the word readiness will be used.

The evidence on family participation according to the perspective of the healthcare team indicates that there are different personal characteristics that affect in one way or another their opinion on the subject, such as age, educational level and years of experience in the ICU.13,14 Moreover, the team's previous experiences of family involvement in the ICU are directly related to the perception of the health care provider.10 Furthermore, studies exploring the perception of the health care team in adult ICUs report that it varies according to the nursing care activity in which the family member will participate.2,11,12,14 Given the relevance of family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient, it is essential to know the willingness of the healthcare team to do so prior to implementation. If it is known which aspects of the willingness are most negative, it is possible to work on improving this willingness and thus achieve greater success in implementation.19

With this in mind, the aim of this study was to determine the level of willingness of the health care team (doctors, nurses, nursing technicians and physiotherapists) to involve the family in the care of critically ill patients in a medical-surgical ICU of a private University Clinical Hospital in the Metropolitan Region of Santiago de Chile. In addition, the aim was to identify the relationship between the individual characteristics of the participants and their level of willingness to participate in family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient.

MethodDesign: cross-sectional correlational study, using a quantitative method and a qualitative approach, the latter through the use of a focus group to improve understanding of the responses provided by the healthcare team to family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient, as the Brief Individual Readiness for Change Scale (BIRCS) was used for the first time in this context.

Setting: the study was conducted in an ICU of a University Hospital in Santiago de Chile, between March and September 2019. The ICU under study consists of 2 medical-surgical units, with a total of 32 beds. It employs 180 people (20 doctors, 70 nurses, 20 physiotherapists and 70 nursing technicians). Visiting hours are extended from 13:00 to 19:00 from Monday to Sunday.

Subjects: the study population consisted of nurse technicians, doctors, nurses and physiotherapists who were actively working in the unit at the time of the study. Non-probabilistic convenience sampling was used. The sample size was calculated based on the study population (180), under the assumption of maximum indeterminacy (expecting 50% proportion) with a confidence interval (CI) of for example 95%, and an estimated precision of 5%, the sample size would be N = 123. Inclusion criteria were: work experience of more than 6 months (beyond the work placement period), direct patient care, not being on any type of leave that implies not being present in the unit (medical leave, maternity leave or other). Those who agreed to participate signed an informed consent form.

The focus group sample was intentional since a representative of each of the groups included in the study was recruited, and the inclusion criterion was to have previously answered the survey.

Variables: the main variable under study was the willingness of the healthcare team to involve the family in the care of the critically ill patient. Given that the literature does not report a specific instrument to measure the level of readiness for this issue, the Brief Individual Readiness for Change Scale (BIRCS).20 was used. This scale was designed to be adapted to any evidence-based practice,20 being used for example in an addictions programme20 and in the context of primary education for children.23 It was culturally adapted and validated in Spanish in Chile by Irarrázabal et al.24 in a study to determine the willingness of primary health care workers to be tested for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). This validation followed the recommended approaches, including back-translation and a face-to-face validation with a group of health professionals prior to its application with 150 participants, where a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.72 was obtained for the global scale. Prior to its application in the ICU setting, the suitability and relevance of the Spanish version was evaluated, replacing the words “rapid HIV test” in the Spanish version with the concept “family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient”. This evaluation was carried out by two nurses with more than 10 years of experience in adult ICU in Chile, in the hospital participating in the study, to corroborate the relevance of the scale with which the ICU participants were to measure the participants, prior to its application.

The scale considers the five pillars representing individual readiness to change: self-efficacy, relevance, organisational time-resources, organisational support and personal valence. The items are assessed according to a Likert scale from 0 to 4 points, where 0 = strongly disagree; 1 = disagree; 2 = neutral; 3 = agree and 4 = strongly agree. The total score is 20 points. For the purpose of this study the scale statement was adjusted to “willingness towards family involvement” (Appendix B Appendix 1).

In addition, this study used a comfort questionnaire, developed through a review of the literature related to family involvement in the ICU, to measure the “comfort level” of the healthcare team on the subject. It consisted of 14 patient care activities described in different research.2,11,12,14. Rojas et al.,25 co-author of this study with experience in the validation of instruments in the area of intensive care, conducted an analysis of these activities in terms of clarity, consistency and relevance. In addition, this questionnaire was reviewed by the same 2 nurses mentioned above, prior to application with the participants. The activities included are related to: grooming and well-being, feeding, transfer and mobilisation of patients, application of lotions, emotional support and companionship. The questionnaire includes a Likert scale from zero to four points, being “0” (very uncomfortable); “1” (uncomfortable); “2” (neutral); “3” (comfortable) and “4” (very comfortable) (Appendix 1).

Finally, the socio-demographic data of the participants were obtained through a questionnaire that included professional and work-related aspects (Appendix B Appendix 1).

Data collection: The questionnaires were given to the participants by a member of the research team to all ICU staff who expressed their intention to participate, prior to a dissemination of the project by the principal investigator at a team meeting. All interested parties completed the questionnaire after signing the informed consent form. After completing the questionnaires, the participants left them in a mailbox provided for this purpose. Data collection from the survey took place between March and August 2019. Once the questionnaire collection process was completed, respondents were invited to participate in a focus group, as mentioned in the initial informed consent. For the focus group, a session was held with those respondents who agreed to participate, led by a trained guide with a Master's degree. The objective was to deepen the participants' opinion regarding family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient. A questionnaire was used for this purpose (Appendix 2), headed by a guiding question: "What do you think about the involvement of family members in the care of the critically ill patient? The focus group was conducted in September 2019, in a meeting room of the unit studied, lasting one hour. Theoretical saturation of the data was achieved where no new ideas emerged from the different focus group participants in relation to the topic.

Data analysis: descriptive statistics (frequency tables and percentages) and measures of central tendency were used to analyse the quantitative variables. In addition, a bivariate correlation analysis was performed between the dependent variable, “willingness” and each study variable: “age”, “sex”, “position”, “academic level”, “years of experience in the ICU”, “previous experience working with families and qualification of that experience” and “comfort index”. The level of statistical significance was set at a p-value of 0.05. The corresponding statistical analysis and tests were carried out with the SPSS® Statistics 25.26

For the data obtained from the focus group, a content analysis was carried out according to Krippendorff27 to identify the themes emerging from the session; COREQ recommendations for data analysis28 were also used. Field notes of the session and verbatim transcription of the narratives were made. The results were triangulated with three members of the research team and finally a member check was made with the session participants via email.

Ethical considerations: this study was approved by the Scientific Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. In addition, authorisation was obtained by letter from the management of the hospital studied and verbally from the head of the ICU.

It should be noted that participants were assured confidentiality and anonymity, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.29 In addition, the ethical aspects of the research were safeguarded by the Emmanuel et al.30 criteria for scientific research. All subjects agreed to participate in the study by signing the informed consent form.

Furthermore, the data obtained from this study were processed in accordance with the legislation on the protection of personal data and the guarantee of digital rights.31

ResultsSocio-demographic variablesThe study population consisted of 120 healthcare personnel, which corresponds to 97.6% of the calculated sample (123), all of whom provide direct care to critical patients in the ICU under study. The mean age was 32 years ± 7.8 with a minimum age of 20 and a maximum of 62 years. Seventy-one percent of the sample (85 participants) were nurses and nurse technicians; most of the participants were women (Table 1). Of those with university studies, 5.8% (7 persons) had postgraduate studies. Most of the participants had less than 5 years of ICU experience (Table 1).

Socio-demographic characteristics of the health team (n = 120).

| Variable | Characteristics | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20−29 | 48 | 40 |

| 30−35 | 49 | 41 | |

| 36−62 | 23 | 19 | |

| Total | 120 | 100 | |

| Sex | Male | 43 | 36 |

| Female | 77 | 64 | |

| Total (n) | 120 | 100 | |

| Position | Physician | 26 | 22 |

| Physiotherapist | 9 | 7 | |

| Nurse | 43 | 36 | |

| Nurse technician | 42 | 35 | |

| Total | 120 | 100 | |

| Level of education | Technical professional | 42 | 35 |

| University | 70 | 58 | |

| Master’s | 6 | 5 | |

| Doctorate/postgraduate | 1 | 1 | |

| Total | 119a | 99 | |

| Years of experience in the ICU | 0−4 | 61 | 51 |

| 5−9 | 35 | 29 | |

| 10 or more | 18 | 15 | |

| Total | 114b | 95 |

ICU: Intensive Care Unit.

The “abbreviated readiness for change scale” used in this study showed a Cronbach's alpha of 0.639 and a measurement error given the standard deviation of 0.156. That is, there is a reliability of the scale considered to be slightly low, but with a low measurement error. Low measurement error is related to a higher reliability of the instrument.32

The results of its application show that the overall willingness of the respondents towards accepting family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient was 13.81 points in a range from 0 to 20 points on the “abbreviated readiness for change scale” (SD: 0.25). In the item-by-item analysis, it could be observed that participants had a higher readiness towards the items alluding to the relevance of family involvement (3.08 ± 0.07), self-efficacy (2.92 ± 0.07) and personal valence (2.92 ± .09) (Table 2). This means that the participants considered family involvement in the context of the critically ill patient to be appropriate for the unit and believe they are mostly able to make this change. However, they show lower scores on those items referring to the organisation's resources, the time required to carry out the innovation and the support that the organisation could provide to implement such a change (Table 2).

Results of abbreviated scale of willingness to changea (n = 120).

| Item | Score (0−4) | Standard deviation (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | 2.92 | 0.07 |

| Relevance | 3.08 | 0.07 |

| Resources/time organisation | 2.38 | 0.09 |

| Organisational support | 2.46 | 0.09 |

| Personal valence | 2.92 | 0.09 |

Of the total number of participants, 68.3% (82 people) reported having had previous experience of working with families; of these participants, 39% were nurse technicians (32 people). Of this sample of 82 people with previous experience of working with families, 78% (64 people) indicated that the experience had been mostly positive or positive, while 5% rated it as mostly negative or negative.

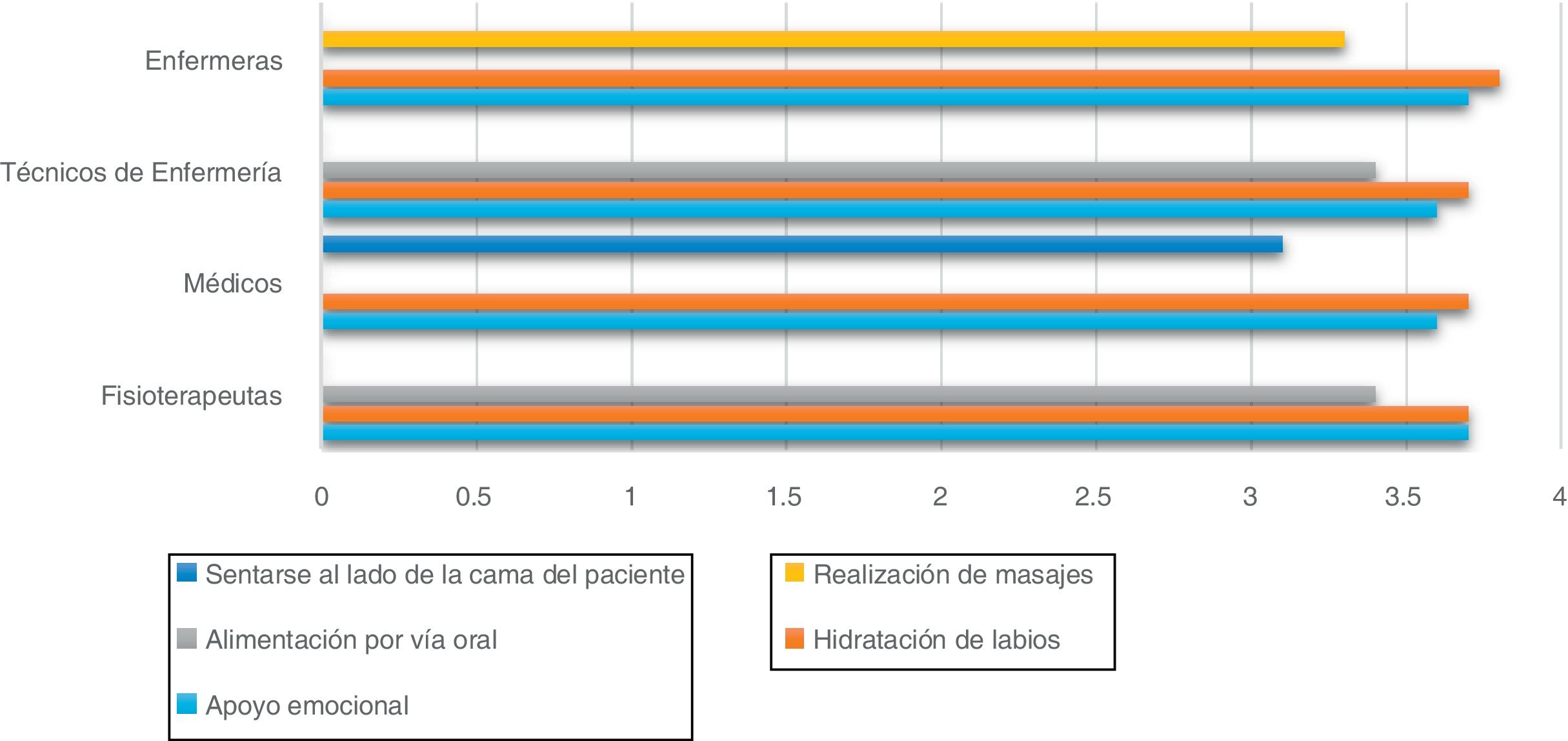

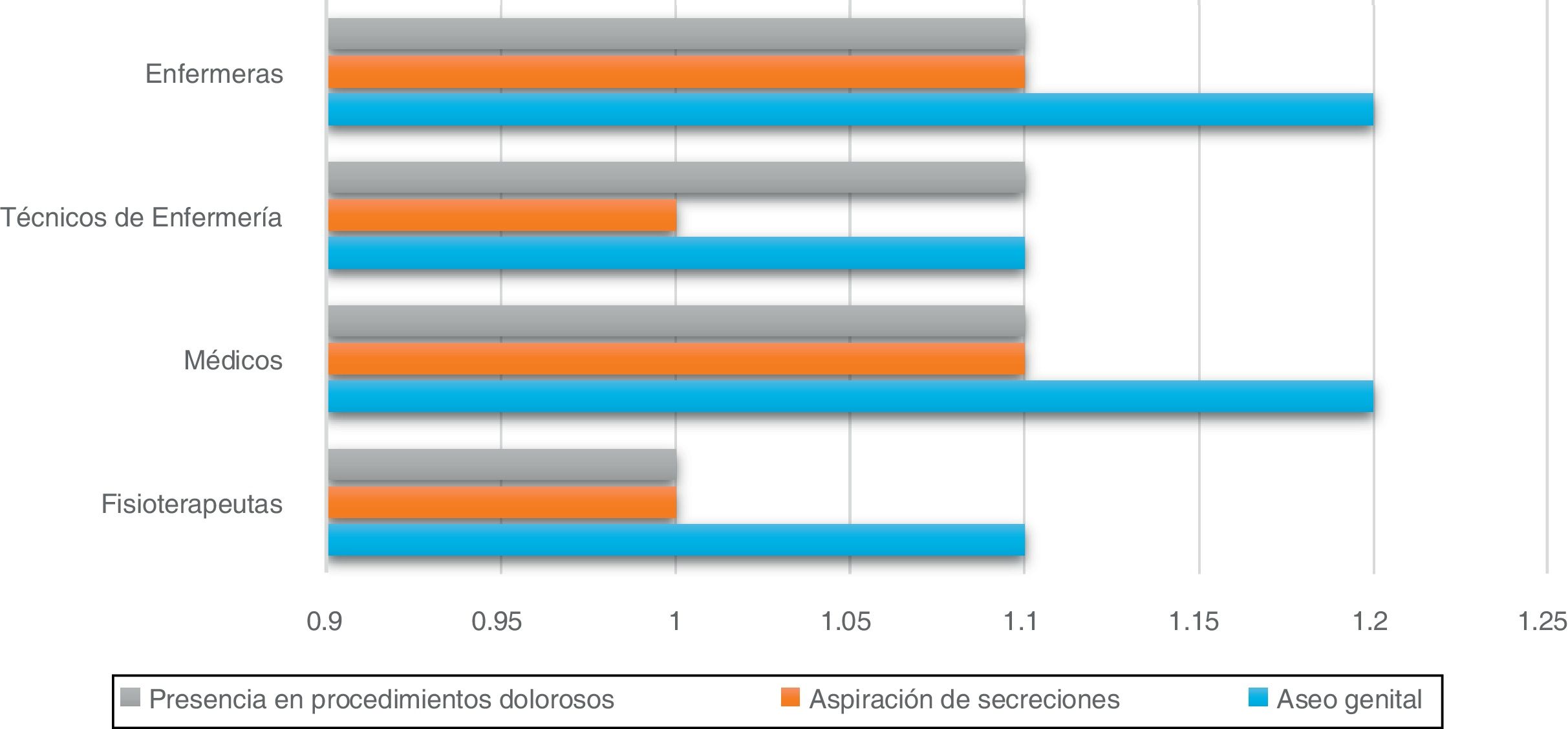

Out of a total of 52 items, the overall “comfort index” was 35 points (SD: 8.315), with higher scores in the group of doctors, nurses and physiotherapists versus nurse technicians (Table 3). Regarding the analysis by item, with a minimum score of zero points and a maximum of 4 points, in general it was observed that the health team felt more comfortable with the participation of the family in activities of patient wellbeing and skin care such as moisturising the lips (CI: 3.71 ± 0.57); emotional support (support, comfort, etc.); (CI: 3.64 ± 0.57) and oral feeding (CI: 3.38 ± .86), among others (Table 3). On the other hand, less comfort was observed in activities related to techniques and procedures sometimes required by critical patients such as secretion aspiration (CI: 1.05 ± 1.14), presence in painful procedures such as removal of drains (CI: 1.08 ± 1.14) and genital hygiene (CI: 1.18 ± 1.14) (Table 3).

Results of comfort index per item.a

| Item | Score (0−4) | Standard deviation (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Moisturising lips | 3.71 | 0.57 |

| Emotional support (support, console, etc.) | 3.64 | 0.65 |

| Oral feeding | 3.38 | 0.86 |

| Giving the patient massages | 3.29 | 0.90 |

| Applying body lotion | 3.27 | 0.90 |

| Sitting beside the patient’s bed | 3.16 | 1.24 |

| Applying physical means to the patient to manage fever | 2.78 | 1.08 |

| Changing patient posture | 2.42 | 1.21 |

| Cavity hygiene (eyes, nose, mouth) | 2.32 | 1.18 |

| Transfer from one place to another (e.g., to a chair) and mobilising the patient (walking) | 1.91 | 1.27 |

| Bathing | 1.82 | 1.29 |

| Genital hygiene | 1.18 | 1.15 |

| Presence in painful procedures such as catheter removal | 1.08 | 1.14 |

| Secretion aspiration | 1.05 | 1.14 |

aTotal comfort index score: 35 points out of a maximum of 52; SD: 8.32.

In particular, the best evaluated activities were similar in all professional categories, only the group of technicians did not consider the activity “moisturising the lips” as one of the best evaluated (“comfortable” or “very comfortable”). On the other hand, all groups agreed on the three worst evaluated activities (“uncomfortable” or “very uncomfortable”). The details of the best and worst evaluated activities for each group can be seen in Figs. 1 and 2. It is worth mentioning that there was no statistical significance in the analysis of the variable “comfort index” with respect to the professional position.

When exploring the relationship between willingness towards family involvement and socio-demographic characteristics, it was observed that there was a significant correlation between willingness and age, a positive rating of previous experience and a higher comfort index. Thus, the younger the age, the higher the readiness towards family involvement (r = −0.215; p = 0.019). While those who rated their previous experience of working with families as positive, showed greater willingness towards family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient (r = 0.304; p = 0.006). Finally, it is observed that a higher comfort index of the participants is associated with a higher level of willingness towards family involvement in patient care (r = 0.495; p < 0.001).

No significant correlation was observed between the role within the health care team and the readiness towards family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient (p = 0.057). However, the group comparison analysis between nurses and nurse technicians showed a negative correlation (f = −2.394; p = 0.002) indicating that the willingness of the technician group is lower than that of nurses to family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient. Similarly, when comparing the groups of nurse technicians and physicians, a negative correlation was observed (f = −2.150; p = 0.025), reflecting that the readiness of the former group is lower than that of the medical team towards family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient.

Focus group outcomesThe scheduled focus group was conducted with eight participants from the health team; a doctor, 4 nurses, a physiotherapist and 2 nurse technicians who participated in the first quantitative stage. At least one representative from each of these groups was selected.

The analysis of the participants' responses to the guiding question: What do you think about the participation of family members in the care of the critically ill patient, followed by the questions in the focus group guide, made it possible to identify five themes that help to explain the results obtained in the quantitative data collection and more specifically in relation to the readiness scale. The 5 themes identified were: 1) Identification of the 5 pillars of readiness; 2) Relevance of the patient's condition; 3) Characteristics of family members; 4) Personal judgement and 5) Family readiness.

Regarding the “Identification of the 5 pillars of readiness”, the staff report being open to allowing the family to participate by including them in the activities of the care of the critically ill patient. The 5 pillars of readiness (self-efficacy, relevance, organisational resources/time, organisational support and personal valence) are identified in their discourse. They point out that the level of readiness increases when they perceive themselves as having the ability to perform a specific task, influenced by their work experience and the confidence they demonstrate, i.e. their perceived self-efficacy. If they feel they are being assessed by the family in their work, they are less willing to include the family in the care, as the following narrative shows: P.3 “... I have allowed family members to watch procedures..., you have to be very sure... but it helps a lot, it leaves them calm and the family realises that there is a job well done... in a way you validate yourself with the family, they are satisfied, calm...”.

Also, with respect to relevance, they affirm that the change is appropriate for the institution, similar to what was stated in the quantitative analysis, arguing that family participation is in accordance with the humanisation strategies that have been implemented in the health institution where the study was carried out. P.3: “Among the humanisation practices that we are trying to involve ourselves in is the family issue... there is a final objective that the family should be part of the patient's care...”.

In addition to the above, with regard to the resource/time aspects, they point out that the physical structure and tools of the unit, in addition to staff turnover and workload, hinder the relationship they establish with families as they have less time available to incorporate them into patient care. This could explain why the item related to resources/time of the abbreviated readiness scale, in the quantitative phase, had the highest score. P.6: “I was thinking that what also makes it difficult for the health team is the rotation of nursing staff. For example, when one changes shifts or there is a change of nurses who are at the bedside with the patient, communication and continuity is slightly lost, because they always get so used to a particular nurse. Another thing in all the shifts is the demand for care, no extra time...a terrible shift, there is no time to educate the family either...”.

In order to achieve family participation, the participants affirmed that organisational support is necessary in terms of having guidelines, protocols and plans of action to encourage the incorporation of the family in the care of the critical patient. This could be related to the fact that in the abbreviated readiness scale, the item alluding to organisational support obtained the second lowest score. P.7: “...as a unit it is not that we have a policy of incorporating the family into patient care, but it is something we do very instinctively...and clearly we need something that is much more protocolised, to establish the procedures in which the family is going to participate...”.

Finally, in relation to personal valence, they say that this subject contributes to personal benefit and/or positive results for the patient, for themselves and for the unit. These results are consistent with the item “personal valence” of the abbreviated readiness scale, which yields one of the best scores. P.1: “It (family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient) is positive, especially in patients who are more agitated, that figure of the family member calms them down a little more, gives them a bit more security...”. P.2: “...the fact that you teach the family member how to show the patient how to walk...is also useful because in a few days that patient will go home with that family member...”.

Other issues not linked to the pillars of the abbreviated readiness scale are related to the willingness of health personnel to involve the family in care.

In terms of the severity and chronicity of the patient, participants noted that the health condition of the patient is a factor that influences the level of readiness of the team for family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient. Specifically, it relates to the chronicity or severity of the patient's condition in routine patient care. According to the participants, the chronic patient is one who has been hospitalised for a long time, more than two to three days, or who has had frequent hospitalisations; they describe them as patients with haemodynamic stability and, therefore, stability in their health condition, which favours participation as care becomes habitual. On the other hand, the serious patient is when the patient's health condition is life-threatening; they state that in these cases the family member does not participate in the care. This is reflected in the following narratives: P.1: “...if they are chronic patients who have been here for a long time, they (family) get involved a bit more because it becomes part of their routine, like coming here, being with them (patients) all day long...”... P.5: “...we have to take into account that they start to learn, when they have been here for a long time the family gets involved and they start to ask questions and they start to learn...” P.6: “... with this condition, when they are in a serious condition, we hope that the family members are not there because the clinical situation of the patient means that one worries first about the vital aspects, until they are stabilised and then there is the family situation...”.

Regarding the “evaluation of the family member characteristics”, the participants indicated that the characteristics of the family members impact the willingness of the health team to involve them, as well as the rating of the previous experience of working with families reported in the instrument. Both the physical capacities and the emotional stability of the family member are aspects considered by the health team, as the following narrative shows: P.2: “... If you are going to make a patient walk, they have to have the physical capacity to help and not become a risk (family member).”

The bond of trust generated between the patient-family-health team triad is another characteristic mentioned that plays an important role in the willingness of the health team. The greater the bond of trust and the better the communication between the actors, the better the health team perceives the experience of family participation. P.6: “... when there is good communication, family members form a bond with the health team and this leads to the participation of the family members”. P.7: “... you also give a vote of confidence to the family and little by little this bond is strengthened..., team work is also carried out with the family”. P.4: “... I realise that sometimes I find it difficult to incorporate the family because it depends a lot on the type of family. There are some families who get in the way of the work with a bombardment of questions or because some parameter is altered and they immediately become distressed... on the other hand there are other relatives who are very willing, they really feel like they are genuine support for the patient, they do not distress the patient, they reassure him/her”.

The fourth theme identified is strongly related to the instrument's Comfort Index and the level of willingness to involve the family in care. Protection of privacy and risk assessment is under the personal judgement of the health care team, which seeks to protect the patient's privacy and intimacy. This criterion was associated with the perceived comfort of the team and the type of care activities in which the family member can participate. P.4: “... there are many patients who are even very self-conscious with their own family... with a ventilated patient you are not going to know... it is a bit delicate because you can go in there and violate the patient a little...”.

On the one hand, the participants point out that the aim is to protect the patient's privacy by not allowing the family member to enter the unit during a procedure, as they could violate the patient's privacy, for example during bathing. They state that if the patient does not have the capacity to express that they want the family member to stay, they prefer to make them leave. P1: “... I mean, when they (the patients) talk, you can ask them for authorisation, but if not, if they are asleep, you really prefer to safeguard their privacy and remove them (the relative) because they (the patients) have no way of saying 'yes, I authorise it'...”.

In relation to the type of activity that generates a greater or lesser degree of comfort in the healthcare team for the family member to participate in care, this depends on whether it is considered easier or more complex to carry out in terms of the risk involved (causing an adverse event for the patient). The care activities that are perceived as favourable to involve the family are those that are defined as “simpler” and involving basic care. For example, brushing teeth, transferring the patient to the chair or moving them, feeding, use of the bedpan or urinal, presence during the cannulation of a central line, postural changes, application of creams, eye hygiene, shaving and aspiration of secretions from the mouth. On the other hand, those perceived as unfavourable to incorporate into the family due to the risk and/or difficulty involved are bathing, genital hygiene, presence during intubation, aspiration of secretions in intubated patients, and oral hygiene in intubated patients. Likewise, there is a greater willingness for the family member to only observe the activity that the staff is carrying out at the patient's side, instead of assisting in its execution. P.1: “From my personal experience, I feel that the easiest way for the family to stay is during healing tasks, even if they don't help, they can observe...”.

Finally, a fifth and last theme emerges called “family preparation”, which was not addressed in the questionnaire and which alludes to the fact that the health team considers it relevant to train the family to participate in patient care as collaborators of care, since the health team is ultimately responsible for it. In some cases, the willingness of the team to involve the family member is negative because they believe that the care activity would be carried out exclusively by a family member who is not trained in this activity, which would imply a greater risk for the patient. P.2: “... yes, I think that collaboration is the key and not to leave it to them (responsibility for care)...”. P.4: “... I imagine that the issue of participation has to be always supervised because the patient is always under the care of the team. Obviously, if we are going to allow the family to participate, we are always going to have to be in a process of continuous education with the family and supervising. What they are going to do is help us, they are not going to have to do things on their own with the patient...”.

This study is a first approach to understanding the willingness of the health care team in an ICU to involve the family in the care of the critically ill patient.

As for authors who previously used this questionnaire, such as Irarrázabal et al.,24 whose study applied the readiness scale to measure readiness for behavioural change related to the application of an HIV test, the scale was adequate to determine the readiness of the health team for activities considered innovative in the ICU, because family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient is not a standard.

The results show that the level of readiness measured was in the middle of the maximum score, although a higher score is desirable considering that the greater the readiness, the greater the success in implementation.18 The results per item of this scale are consistent with the research of Al Mutair et al. and Heras et al.2,4 on family engagement in the critical care setting, in that they recognise the benefits of family engagement for the institution and staff in general, but also point to both personal and organisational barriers that need to be addressed for implementation.2,4 Thus, the item associated with relevance was identified as having a higher score, meaning that participants consider family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient to be appropriate and beneficial to the unit. In addition, the item associated with personal valence, understood as the perceived personal benefit from the change, was one of the best evaluated items, similar to what is described in the studies mentioned above.2,4

However, items associated with organisational support and organisational resources/time were given the lowest scores in this study. These results are similar to those reported in Zaforteza et al., conducted with various ICU professionals. Zaforteza et al33 also identify that the family may hinder the provision of patient care due to factors such as physical space, and highly mechanised work routines that encourage working without “spectators”. The latter does not appear in the current study, but could be another element that affects the willingness of the health team to involve the family in the care of the critically ill patient.

With regard to demographic characteristics, specifically age, the results of this research show that the lower the age, the greater the willingness to involve the family in the care of the critically ill patient. This is similar to that reported by Hetland et al.13 However, Al Mutair et al.2, whose study was conducted with similar professionals and different geographical contexts, report that age does not influence family involvement in care. The different findings reported in the studies presented regarding age as a factor influencing family involvement could be due to the fact that they were conducted in different socio-cultural contexts. Here, there could be other demographic variables that are preponderant given the setting of the studies, and the existing health system, among others.

In terms of previous experience, the results of this study show that willingness is influenced by the team's previous experience of family involvement and positive evaluation of that experience. These results are similar to those reported by McConell and Moroney,10 who found that nurses who had had negative previous experiences were less willing to include the family in the care of the critically ill patient.10

The perception of comfort with family involvement in certain care activities was similar to that reported by Hetland et al.13 whose study showed that they feel more comfortable with family involvement in activities related to basic care, such as applying lotions or massaging the patient, and less so in activities considered more intimate or invasive, such as bathing and genital hygiene, as they evaluate the possible benefits and risks for the patient. These results are consistent with the present research in that all the groups studied report greater comfort in basic care activities such as applying lotions and, on the other hand, less comfort in activities that could violate the patient's privacy, such as genital grooming. A 2015 literature review on the need for the role of the patient's relatives in the ICU reports that some activities that relatives may perform are massages, skin hydration and passive mobilisation of the limbs.34 Likewise, in relation to care that the participants were not comfortable with, such as secretion aspiration, the literature also shows that the healthcare team, especially the nurses, are less willing to do this, as it is considered a more complex action that entails greater risk for the patient.12,13,20

As for the qualitative results, the analysis of the focus group made it possible to probe into the issues addressed at the quantitative level; in addition, it made it possible to identify new ones that facilitated understanding, particularly of the willingness of the health care team to involve the family. In this context, from the analysis of the focus group, themes independent of the five pillars of readiness emerged, such as the seriousness of the patient's condition, which hinders family participation, and, on the contrary, the chronicity of the patient's condition, with care that becomes routine, favours family participation. This finding is consistent with the study by Hetland et al.,35 in which nurses express that there are times when the patient's condition of severity makes family participation in care not possible; consequently, they do not involve family members in these cases.

Likewise, establishing a relationship of trust between the family and the healthcare team has been described, as in this study, as a factor favouring family involvement in the care of the critically ill patient, as it has been associated with better previous experiences. This is described by Heras et al.36 and Davidson et al.37 in their action plans and guidelines for humanisation in care, stating that a key aspect for a successful care process is communication between patient, family and health care team.The health care team's concern for the protection of patients' privacy was found to be relevant in the focus group. This is also an important aspect in the study by Liput et al.,20 who state that maintaining the patient's privacy is a challenge because the patient cannot express his or her willingness to want or not want the presence of the family member in his or her care. Zaforteza et al.30 further state that because the ICU is an open distribution space, the presence of relatives could infringe on the patient's privacy, consistent with the narratives of the focus group participants in this research.

As a final theme emerging from the focus group analysis, it was noted that participants considered training of family members to be essential in order to involve them in the care of their loved one. Similar findings are reported by Hetland et al.13 who acknowledge that while involving the family in the care of the patient improves communication between the actors involved, it is necessary to have family members trained in these tasks. On the other hand, current evidence and international humanisation plans support family involvement and urge the health team to consider the family as a “partner in care” and to integrate them in patient care activities such as hygiene, feeding, early mobilisation or rehabilitation, under the supervision of the health team.5,38 The latter is mentioned in the focus group of this research, in which it is stated that family participation should be supervised as the ultimate responsibility for the patient's wellbeing lies with the staff in charge.

Finally, as limitations of the study, the abbreviated scale of readiness to change shows results that allow a first interpretation of the level of readiness of the sample, considering that it is interpreted from an established minimum and maximum score. However, because the scale has been used in other settings and was adapted for the first time to the context of family involvement, the results should be analysed with this limitation in mind. The Cronbach's alpha obtained in this study was below 0.7, which could indicate a weak relationship between the questions.

Furthermore, the sample of this study was selected by convenience, so the results cannot be extrapolated to other critical patient contexts, and more evidence is needed in other adult ICUs in the country. Finally, the method of data collection was self-reporting, so there could be a bias of desirable responses in relation to the perspective and the humanisation plan of the institution studied.

ConclusionThis research study made it possible to determine, by means of the BIRCS scale, the level of willingness of the healthcare team in an ICU in Santiago de Chile, with regard to family participation in the care of the critically ill patient. The overall results showed a medium level of willingness (13.8/20 points). Specific factors influencing willingness to participate in family involvement were identified as positive previous experience of family involvement, especially in relation to family interventions related to skin and nutrition, and being young medical professionals and nurses. Other factors related to the characteristics of family groups such as knowledge, skills and closeness to the health care team, as well as those related to the severity of the patients, need to be analysed in future research that addresses family involvement as a central element of the care that should be provided in intensive care units, in order to make these care environments more inclusive and humanised.

It is important to consider the willingness of health care staff to consider new care strategies such as family involvement in the care of critically ill patients in ICU services. The factors identified in this study associated with the willingness of the healthcare team can guide future decision-makers and teams in ICU services in the implementation of this care.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

To the Hospital Clínico Red de Salud UC Christus, to Camila Molina González, nursing student, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile for support in data collection and to MNS Camila Villarroel Fuenzalida, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, for support as focus group guide.