The study aim was to explore the experience of doctors and nursing assistants in the management of physical restraint (PR) in critical care units.

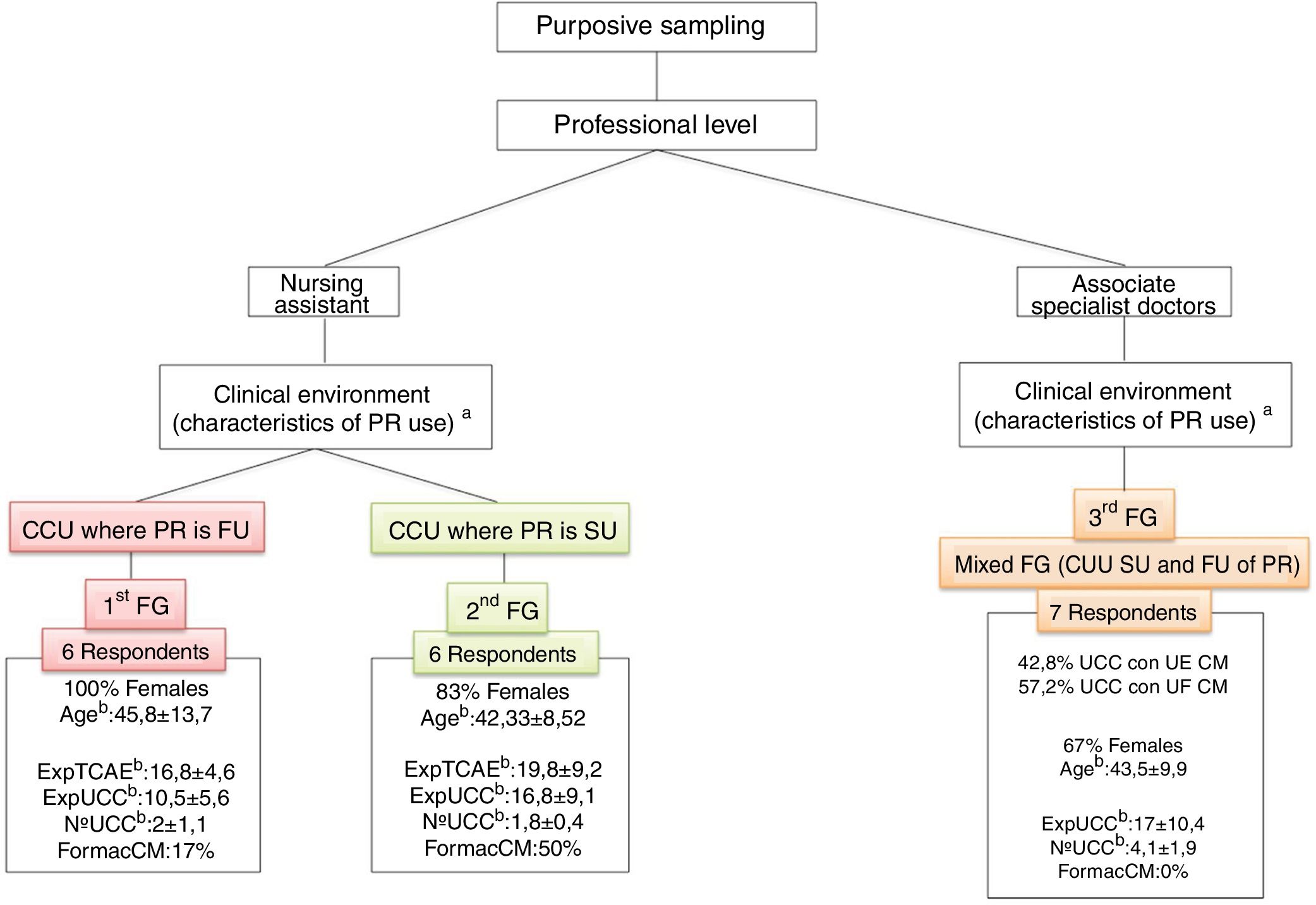

MethodA multicentre phenomenological study that included 14 critical care units (CCU) in Madrid (Spain). The CCU were stratified according to their use of physical restraint: “frequently used” versus “seldom used”. Three focus groups were formed: the first comprised nursing assistants from CCUs that frequently used physical restraint, the second comprised nursing assistants from CCUs that seldom used physical constraint, and the final group comprised doctors from both CCU subtypes.

Sampling method: purposive. Data analysis: thematic content analysis. Data saturation was achieved.

ResultsFour principle themes emerged: 1) concept of safety and risk (patient safety versus the safety of the professional), 2) types of restraint, 3) professional responsibilities (prescription, recording, and professional roles) and 4) “zero restraint” paradigm. The conceptualisation regarding the use of physical contentions shows differences in some of the principal themes, depending on the type of CCU, in terms of policies, use and management of physical constraint (frequently used versus seldom used).

ConclusionsThe real reduction in the use of physical restraint in CCU must be based on one crucial point: acceptance of the complexity of the phenomenon. The use of physical restraint observed in the different CCU is influenced by individual, group and organisational factors. These factors will determine how doctors and nursing assistants interpret safety and risk, the centre of care (patient or professional-centred care), the concept of restraint, professional responsibilities and interventions, interactions of the team and the leadership.

El objetivo fue explorar la experiencia de médicos y Técnicos en Cuidados Auxiliares de Enfermería (TCAE) respecto al manejo de contenciones mecánicas (CM) en Unidades de Cuidados Críticos.

MétodoEstudio fenomenológico multicéntrico que incluyó 14 Unidades de Cuidados Críticos (UCC) de Madrid (España). Las UCC fueron estratificadas en función del uso de contenciones mecánicas: “uso frecuente” versus “uso escaso”. Se realizaron tres grupos de discusión: el primero compuesto por TCAE procedentes de UCC con uso frecuente de contenciones mecánicas, el segundo grupo por TCAE de UCC de uso escaso de contenciones mecánicas y el último grupo por médicos de ambos subtipos de UCC. Método de muestreo: por propósito. Análisis de datos: análisis temático de contenido. Se alcanzó la saturación de los datos.

ResultadosEmergen cuatro temas principales: 1) concepto de seguridad y riesgo (seguridad del paciente versus seguridad del profesional), 2) tipos de contenciones, 3) responsabilidades profesionales (prescripción, registro y roles profesionales) y 4) paradigma “contención cero”. La conceptualización sobre el uso de contenciones mecánicas muestra diferencias en algunos de los temas principales dependiendo del tipo de UCC en cuanto a políticas, uso y manejo de contenciones mecánicas (uso frecuente versus uso escaso).

ConclusionesLa reducción real del uso de contenciones mecánicas en UCC debe partir de un punto clave: la aceptación de la complejidad del fenómeno. El uso de contenciones mecánicas observado en las diferentes UCC está influenciado por factores individuales, grupales y organizativos. Estos factores determinan las interpretaciones que médicos y TCAE realizan sobre seguridad y riesgo, el centro del cuidado (cuidado centrado en el paciente o en el profesional), el concepto de contención, las responsabilidades e intervenciones profesionales, y las interacciones del equipo y el liderazgo.

The use of physical restraint (PR) in critical care units is currently being reviewed. Although all studies give nurses a major role in the management of PR, this study examines in depth the conceptualisation by other actors such as doctors and nursing assistants who seem to be influencing nurses in terms of the joint conceptualisation of safety and risk, the concept of PR and the responsibilities and roles of the different professionals, etc. The discourse of doctors and nursing assistants opens the way to the possibility of “zero restraint” care practice and shared prescription if PR is strictly necessary.

Implications of the studyThe “zero restraint” paradigm is proposed as achievable from a comprehensive patient-centred care approach. A culture of safety focused on wellbeing, and judicious and consensual decision-making in which nurses are identified as key figures.

We have recently been witnessing a timid, but growingly critical look at the use of physical restraint (PR) in all areas of healthcare including critical care.1–11 Although for years the use of PR in critical care units (CCU) has been forgotten and kept silent, assuming it as an inevitable part of the care of critical patients,4,6,12,13 various authors and scientific societies are starting to take small steps forward by questioning the relevance of the measure and inviting individual reflection in each case, to assess whether there are options other than the use of PR or whether other approaches could help to reduce its use.1–11 “Zero restraint” policies are even being suggested.1

In the case of PR, even its name is controversial14: in the institutional field, the use of the name “therapeutic immobilisation” has been recommended (assuming its therapeutic effects).15 However, today the most appropriate names are “physical restraint” or “physical containment”, denying any therapeutic effects.9,10,14 Panels of experts, ethics committees and experts in care quality, among others, are also participating in this discussion on how it should be correctly conceptualised.9,10,14

The term PR will be used for this study, which is defined as “any action or procedure that prevents a person’s free body movement to a position of choice and/or normal access to his/her body by the use of any method, attached or adjacent to a person’s body that he/she cannot control or remove easily”.7,14

Although there are very few studies that analyse PR use in CCUs worldwide, the prevalence of PR use in CCU differs widely between countries. In the UK or Scandinavian countries PR is considered abusive and immoral, with close to 0% prevalence of use.1,5,11,12,16,17 In the other countries that have published some data on the subject, the prevalence seems high: 23% of patients admitted to CCU in the Netherlands or 76% of patients on mechanical ventilation in Canada.1,11,16,18–25 In Spain, the only data published to date show a prevalence of 15% and 43.9%.12,13,16 However, comparison of data between countries could be complicated by contextual differences in the type of patients admitted to CCU (with or without mechanical ventilation) or the existence of intermediate care units, among other associated factors.14,16

It seems clear at present that the systematic use of PR in CCU is increasingly difficult to justify, since adverse effects at both a physical and psychosocial level are well documented in the literature, and the use of PR undermines patient autonomy and dignity.6,7,10,11,26 In relation to ethical principles, its use could be justified on the basis of the principle of beneficence.7,10 However, a growing number of studies question the effectiveness of PR in achieving the objective proposed in CCU: to prevent self-removal of life support devices, such as the endotracheal tube.1,5,11,18,27–30 Moreover, PR is now starting to be viewed as deliriogenic and a relationship between PR and post-traumatic stress on discharge from CCU is starting to be suggested.1,3,11,24,31

Furthermore, in areas where the use of PR has been worked on in greater depth (geriatrics and mental health) the use of PR has been recognised as a complex and multifactorial issue in which a multitude of individual, group and institutional variables come into play and in which all parties must be involved to achieve a real decrease in its use.6,7,32–34 In this sense, different authors point out that PR could conform to the “iceberg theory”: the tip of the iceberg would be the use of PR, but at deeper levels there is an intricate network of relationships of different elements.34,35 In this theory, all healthcare actors would influence the main actors – nurses - in the use of PR.4,6,17,33,36 Similarly, other authors are beginning to approach the use of PR from new explanatory models, analysing the effect of social influences on nurses, who are now generally in charge of managing PR.4,34,36 In this regard, Vía-Clavero et al. apply the “theory of planned behaviour” to the use of PR in ICUs, finding that nurses are conditioned not only by intrapersonal factors, but also by interpersonal factors (exercised by peers and other ICU professionals) in the final process of intention and decision about the use of PR.6

In this regard, although nurses play a core role in the management and handling (placement, maintenance and removal) of PR, they do not appear to be alone in this decision-making process.4,6,17,33,36 Doctors and nursing assistants may be exerting a constant and powerful (and often invisible and discrepant) influence.4,6 The recognition of this interdisciplinarity in the use of PR seems consistent with the recognition of the complexity of the phenomenon made by other areas of social healthcare.6,7,32–34

Qualitative methodology is proposed as a powerful tool for the initial exploration of multifactorial problems, with multiple underlying elements, and marked by their invisibility.37,38 This study, therefore, aims to approach how professionals other than nurses (doctors and nursing assistants) conceptualise the use of PR in CCU and other associated factors, as well as how their experience influences nurses’ decision-making.

ObjectivesWith this background, the main aim of this study was to gain an understanding of the experience of doctors and nursing assistants in the management of PR in CCU.

To that end, we will specifically try to describe the experience of doctors and nursing assistants with regard to the decision-making process (placement, maintenance and removal) related to the use of PR in CCU; explore the different professional roles with respect to the management of PR of those involved in the care of the critical patient; understand the experiential differences of doctors and nursing assistants with regard to the use of PR (frequent versus low use) according to the environment in which they are immersed, and identify the determining factors that the doctors and nursing assistants indicate to enable them to work under the “zero restraint” paradigm.

MethodStudy designA qualitative phenomenological interpretive study39 that enabled an in-depth exploration of the experience of doctors and nursing assistants with regard to the management of PR in critical patients, as well as learning how this experience can influence nurses, the main actors involved in the management of PR in CCU.

Scope of the studyThe data collection took place between December 2015 and March 2017 and included professionals (nursing assistants and doctors) from CCUs belonging to 10 secondary and tertiary level public hospitals of the Community of Madrid. The nurse:patient ratios of all the CCUs ranged from 1:2 to 1:3, and the nursing assistant:patient ratios ranged from 1:4 to 1:5, in both cases depending on the work shifts (day versus night).

Participants and samplingPurposive sampling was carried out.37 In general, the inclusion criteria were: professionals (nursing assistants or doctors) who, at the time of the focus group (FG) were undertaking care activity in CCU, with a minimum of 3 years’ clinical experience in CCU (in the case of the nursing assistants) and who explicitly agreed to participate in the study by signing the informed consent form. The doctors had to have completed their residency training period and therefore hold the title of associate specialist in intensive care and/or anaesthetics and resuscitation. In the preparation of the participants’ datasheets the following were considered discourse-modulating experience criteria: general length of clinical experience, length of experience in CCU, number of CCUs they had worked in and having received specific training in PR. Other sociodemographic data such as gender and age were also collected.

In addition to the above criteria, and in continuity with the line of work already started,4 the CCUs to which the professionals belonged were stratified into “CCUs where PR is frequently/systematically used” (CUUs where PR is FU) or into “CCUs where PR is seldom/individually used” (CCUs where PR is SU). This stratification was made according to the frequency and criteria of applying PR (indications for use of PR, the existence of a standard or protocol guiding the use of PR specifically in critical patients, etc.). Both questions were included in a self-completed questionnaire (given the lack of valid resources in the literature). In this study, of the total 14 CCUs, 8 were CCUs where PR is FU and 6 were CCU where PR is SU. This classification, already explored satisfactorily, meets the need to obtain data to allow the comparison of clinical profiles consistent with different ways of understanding PR according to the clinical environment.

The respondents were accessed through care researchers (nurses) working in each of the centres. Data collection allowed data saturation by crossing the results with those previously collected in the FGs held with nurses.

Data collectionA total of 3 FGs were held with the participation of 6 professionals per group: 2 FG with nursing assistants (one FG with nursing assistants from CCUs where PR is FU and one FG with nursing assistants from CCUs where PR is SU) and a FG with doctors (mixed group with professionals from both subtypes of CCU and from both specialities). We sought criteria of heterogeneity in terms of work centre and years of professional experience, both of which highlighted as relevant in the references.16

The aim during the FGs was to build a shared sense structure in the group, based on individual and subjective experience of PR management in CCU, and to jointly explore the factors that favour/limit the use of PR guided in a superficial and non-directive way by the FG moderator.40 As in previous phases of this study, it was very advantageous pragmatically to turn the FGs into mini FGs,41 allowing appropriate discursive interactions at the same time as synergies in the discourse, building a group feeling towards the object of study, especially in more complex aspects or those requiring theories to be partially developed. These types of strategy and interaction for complex issues seem to be more difficult in FGs with a larger number of respondents.

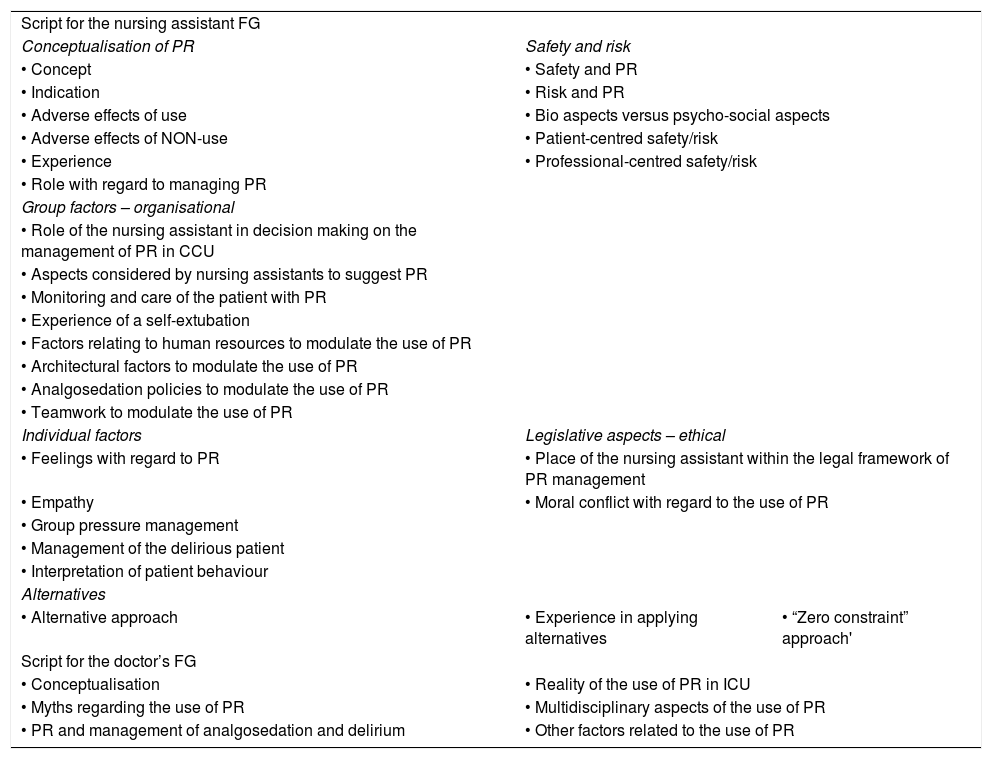

The 3 FGs were moderated and led by the principal investigator (PI), accompanied by a member of the research team with experience in qualitative research and who acted as an observer during the FG. The same script was used for the FG with nursing assistants (Table 1). For the FG with doctors, after preliminary analysis of the nursing assistant FG and triangulation with the results of the FG with nurses from previous phases of the study,4 a new, more directive script targeting specific aspects (Table 1) was created to increase the productivity of the FG. In this regard, the doctors’ FG could be understood as a true focus group,42 being more directive and integrating professionals from both subtypes of CCU (“frequently used” vs. “seldom used”) who had to give a shared response to more specific aspects of the use of PR in CCU from the sensitivities and realities of all involved.

Script used to moderate the focus groups.

| Script for the nursing assistant FG | ||

| Conceptualisation of PR | Safety and risk | |

| • Concept | • Safety and PR | |

| • Indication | • Risk and PR | |

| • Adverse effects of use | • Bio aspects versus psycho-social aspects | |

| • Adverse effects of NON-use | • Patient-centred safety/risk | |

| • Experience | • Professional-centred safety/risk | |

| • Role with regard to managing PR | ||

| Group factors – organisational | ||

| • Role of the nursing assistant in decision making on the management of PR in CCU | ||

| • Aspects considered by nursing assistants to suggest PR | ||

| • Monitoring and care of the patient with PR | ||

| • Experience of a self-extubation | ||

| • Factors relating to human resources to modulate the use of PR | ||

| • Architectural factors to modulate the use of PR | ||

| • Analgosedation policies to modulate the use of PR | ||

| • Teamwork to modulate the use of PR | ||

| Individual factors | Legislative aspects – ethical | |

| • Feelings with regard to PR | • Place of the nursing assistant within the legal framework of PR management | |

| • Empathy | • Moral conflict with regard to the use of PR | |

| • Group pressure management | ||

| • Management of the delirious patient | ||

| • Interpretation of patient behaviour | ||

| Alternatives | ||

| • Alternative approach | • Experience in applying alternatives | • “Zero constraint” approach' |

| Script for the doctor’s FG | ||

| • Conceptualisation | • Reality of the use of PR in ICU | |

| • Myths regarding the use of PR | • Multidisciplinary aspects of the use of PR | |

| • PR and management of analgosedation and delirium | • Other factors related to the use of PR | |

PR: physical restraint; FG: focus group; CCU: Critical Care Unit.

The FGs lasted approximately 90 min and took place in a quiet environment, without interruptions and unknown to both the researchers and all the FG members in order to avoid differences in perceived wellbeing. The FG were audio recorded and transcribed by an external, specialist company for subsequent analysis.

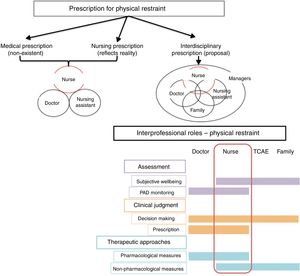

Data analysisA thematic analysis of the content of the discourse was carried out, free of theoretical frames of reference. 43,44 In an attempt to ensure the latter, the analysis was carried out by a different member of the team than the main analyst of the previous phase of the study. Finally, however, the results of the analysis were shared and discussed to be nuanced and polished, thus achieving solid and critical integration. The steps taken to co-construct the meaning of this experience are described below. Firstly, the discourse of the nursing assistants was analysed, and secondly, that of the doctors. Finally, a comparison was made, identifying common and differential elements, generating proposals linked to the influences inherent to sharing the same object of care. For each of the groups, the analysis began with a re-reading of the transcripts until the available information was known in depth. The significant discursive fragments were then identified to understand the study phenomenon in relation to the objectives. These discursive fragments were coded, and the codes assigned were defined (some of these definitions provided the seed for future memoranda or analytical reflections). Once the discourse had been fragmented into meaningful units, these were regrouped into thematic groups according to affinity or complementarity of meaning, in order to then build relationships between the different thematic groups and between the different elements within each thematic group. Once these relationships had been established, primary theoretic proposals were generated for each of the professional groups. These proposals were compared by identifying common and differential elements (parallel, convergent, divergent, tangential perspectives…) in order to generate new, more solid proposals with great potential to illustrate the results worked on previously from the experience of nurses.4 In order to stimulate the capacity for analysis (theoretical sensitivity) and integration of meanings, diagramming strategies were used which, in their most advanced versions, give the figures that illustrate the results.

Atlas.ti (version 7.5.18) software was used to support the data analysis process.

Criteria of rigourWe monitored the epistemological adaptation to the object of study in terms of relevance, validity and reflexivity.45 With regard to validity, triangulation was carried out between researchers during the analysis process, with sessions for sharing and consensus on the inferences made by each of the analysts, return sessions with clinical experts and some respondents (member checking), and verification of quality criteria for reporting qualitative research using the COREQ proposal.46 In terms of reflexivity, the proximity of the PI to the study phenomenon could have led to an interpretative bias; however their broad knowledge and experience in the subject (being-in-the-world) were used critically and judiciously, facilitating the research question and the analysis. In addition, as the study was carried out the PI kept a reflective journal and observational, inferential and theoretical memos that helped them to identify and bring to light preconceived ideas and guide the process in the different phases of data collection and analysis.47

Ethical aspectsA favourable opinion was received from the clinical research ethics committees of each of the centres involved. Department heads and nursing supervisors authorised the inclusion of the CCUs in the project. Each respondent was informed of the study objectives and method and showed their approval by signing the informed consent form.

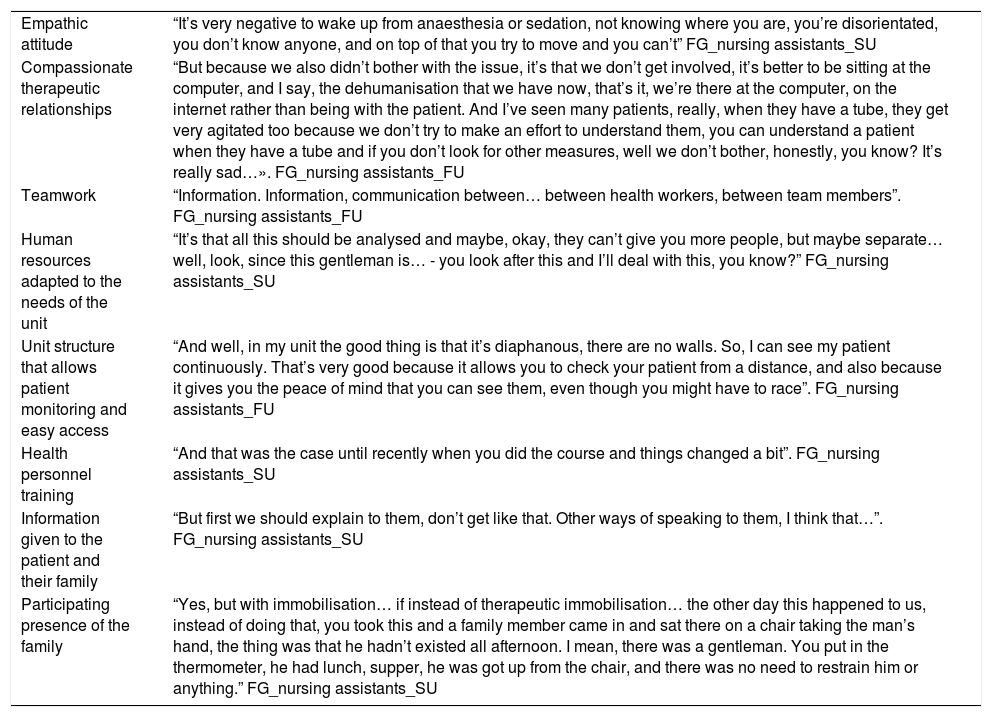

ResultsA total of 18 CCU professionals participated, grouped into 3 FGs. Fig. 1 shows the characteristics of the sample and of the FGs according to the population criteria and sampling procedures used.

Characteristics of the focus groups according to population criteria and sampling procedures.

aConceptual hypothesis: the clinical environment conditions the conceptualisation of PR use.

bData expressed as mean ± standard deviation. PR: physical restraint; ExpTCAE: years of experience as a nursing assistant; ExpUCC: years of experience working in critical care units; FEA: associate specialist doctor; FormacCM: percentage of respondents with specific training in physical restraint, not necessarily in the field of critical care; FG: focus group; N.º UCC: number of different critical care units in which they have undertaken their professional activity; CCU: critical care units; SU: scarce/individualised use; FU: frequent/systematic use; TCAE: nursing assistant.

Four main topics emerge: 1) concept of safety and risk; 2) types of restraint; 3) professional responsibilities; and 4) “zero restraint” paradigm, with nuances in the conceptualisation depending on the type of CCU in terms of PR management (frequently used versus seldom used).

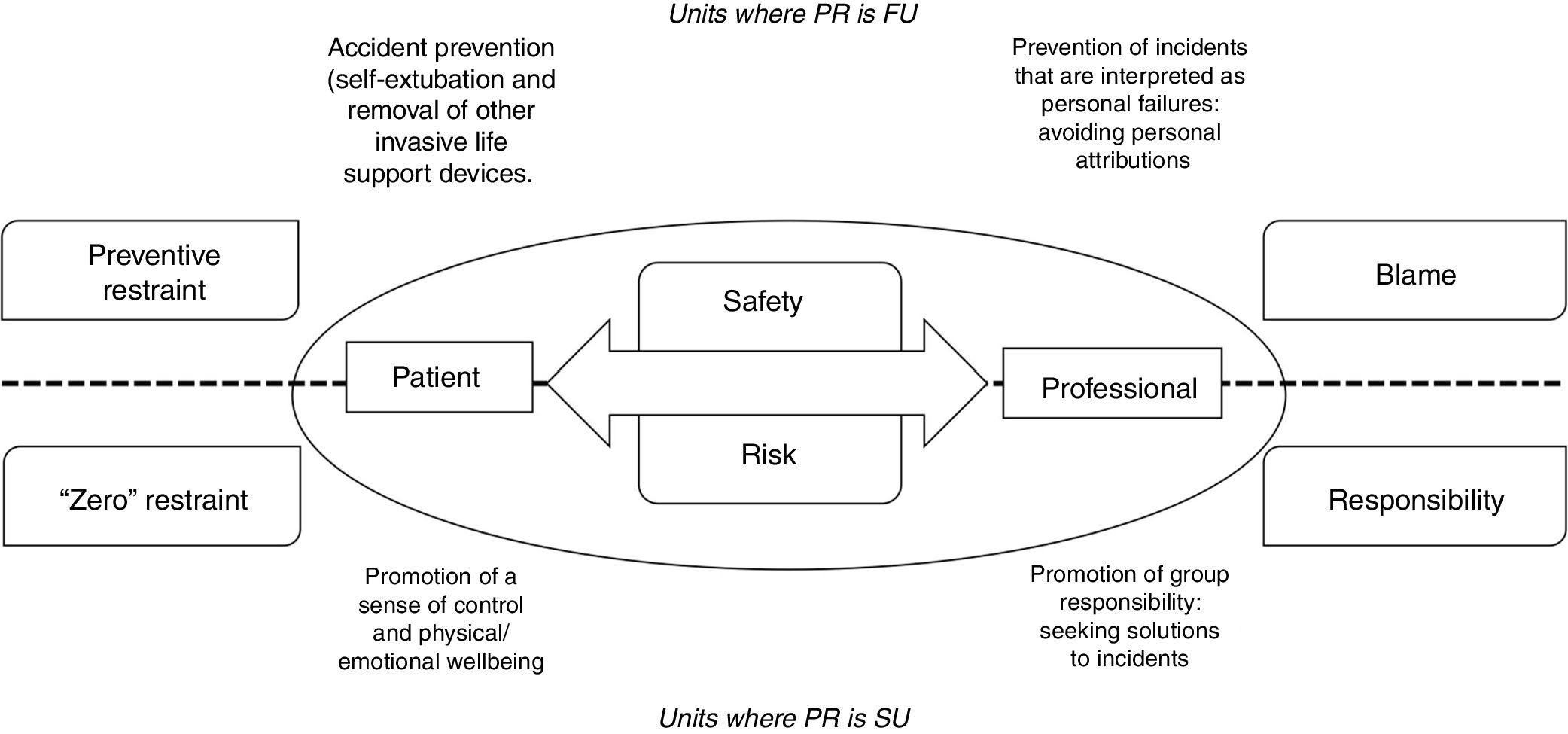

Concept of safety and riskThe use of PR has as its theoretical basis the concept of safety and risk managed by professionals. The concept of safety is viewed from two perspectives that are placed at opposite poles of the same continuum: safety referring to the patient and safety referring to the professional in relation to their performance at work (Fig. 2).

In CCUs where PR is FU, the discourse of the nursing assistants was based on risk prevention (principally the risk of self-removal of invasive devices) which they conceptualised as “preventive restraint”, together with the avoidance of “blame” in the event of accidents.

“Preventive restraint” refers to the habitual and systematic use of PR (not individualised) with the idea of ensuring patient safety. This preventive attitude presupposes that all patients admitted to CCU (mainly those who are being taken off sedation to then remove mechanical ventilation) are exposed to universal risk situations (not considering the particular situation to which the patient is exposed and how he or she interacts with it). This risk of suffering accidents (such as self-extubation) is attributed to patient behaviour such as psychomotor agitation without considering the causes or the magnitude of the consequence of the risk or the preventive interventions themselves (restraint).

Mixed doctors’ FG: “[…] a patient who was awake, was a little agitated […] and then they came to put the wrist restraints on him […]. And I say, ``What are you doing, when I’m talking to them?'' ``No, no, it’s in case they get agitated''. […] and a lot of patients as they come from the operating theatre, or if you’ve just intubated them, the wrist restraints are on.”

In relation to healthcare professional-centred safety, there is a culture that focuses on defensive intervention with the aim of minimising possible incidents that can be attributed to the professional. “Preventive restraint” is established as a defensive shield to avoid incidents while one is directly responsible for the patient

In contrast to “preventive restraint”, in the units where PR is SU, the discourse of the doctors and nursing assistants shows their commitment to promoting the wellbeing and comfort of the patient by avoiding protocolised interventions and using individualised assessment to guide clinical judgment and decision making. The objective is to use PR in the fewest possible cases and always conscientiously (justified intervention, bearing in mind possible complications from its use).

FG_nursing assistants _SU: “[…] minimal restraint […] and conscientiously […]. Well … I can’t conceive of preventive (restraint). I mean, if we are already saying that it’s a complicated issue to use therapeutic immobilisation, if we use therapeutic immobilisation, if we make it preventive… What do we do? Do we tie everyone up before we wake them up?”.

Mixed doctors’ FG: “See what you’ve done? I told you I had to keep him tied up”, and this creates a dynamic […] it’s a question of the global dynamics of people, that is, the feeling of thinking what you shouldn’t do […] more in specific cases and times, it has to be a collective thing because if there’s someone less inclined to do it it’s like they’re being told off with the idea of “Do you see what you’ve caused?”.

On the other hand, the concept of safety and professional risk is approached from a different perspective. Thus, in the CCUs where PR is SU, both the doctors and the nursing assistants interpret the risk of undesired events as intrinsic to professional practice, although resources and advances in knowledge mean that these are less frequent, and work is carried out with much greater safety.

Mixed doctors’ FG: “Truly inevitable risks […] are very few, what happens is that with current knowledge, since there are things that we now cannot prevent, but if you analyse all the factors that influence the famous Emmental cheese, with all those little holes, if you go around plugging those holes, well, there comes a time when it is very difficult for those mistakes and errors to be made”.

Thus, they do not understand the use of PR as a resource to avoid incidents that could demonstrate personal failure in professional practice, but they understand that the real solution to undesired events occurring is a sense of group responsibility.

Mixed doctors’ FG: “… it is the fear of feeling guilty and being blamed for something that you think may be a personal failure when it’s really the usual thing, we are going to look for the guilty party and we are not going to look for solutions and why things happen […] working together with the whole team and not looking for blame but trying to find solutions”.

In this context, the concept of security acquires a more humanistic perspective focussed on the subjective experience of the patient and a holistic approach to care.

FG_nursing assistants_SU: [If we were to ask a patient: What does it mean to you to be safe in an ICU, what would you say? [Think about it]. “To be cared for, […] to be accompanied, not to feel alone. They know that they are being cared for, watched, protected. That they are with good professionals […] that they trust the professionals”.

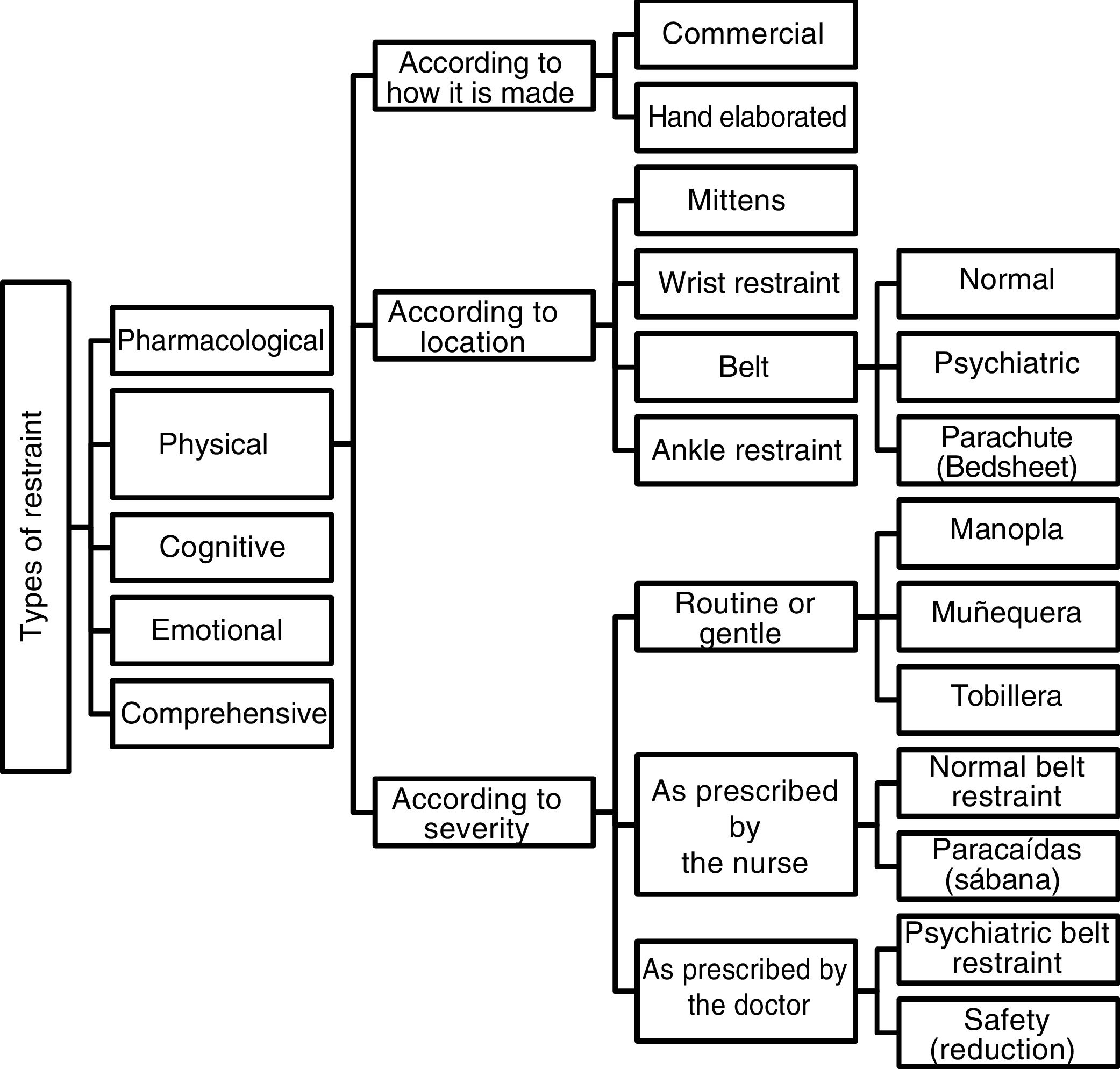

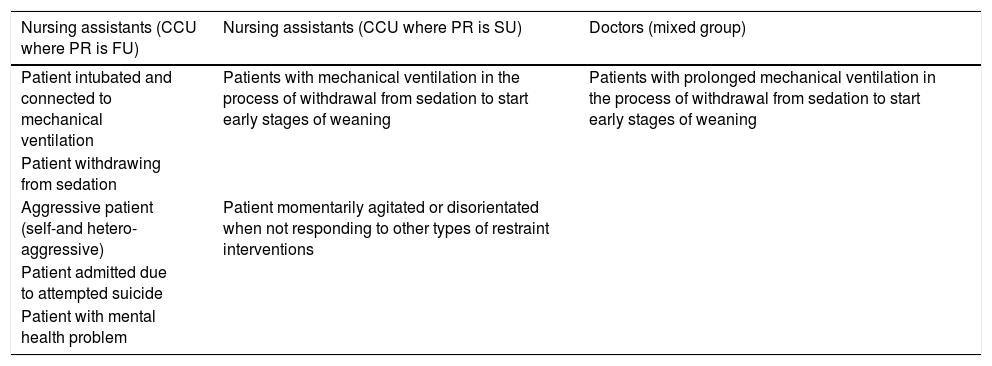

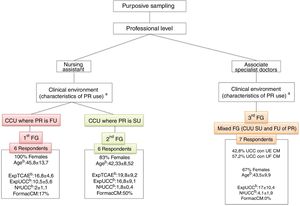

Types of restraintIn addition to the classification of PR by the nursing assistants according to how it is made, placed or its severity (Fig. 3), it is interesting to note that in the discourse of the nursing assistants from units where PR is FU only mentions of pharmacological and physical restraint (PR) are identified. The nursing assistants from units with SU, however, refer to other types of restraint such as cognitive, emotional and, as a whole, those that would be termed “comprehensive restraint”. The indications for the use of PR identified by the nursing assistants from both types of CCU and the doctors (Table 2) reinforce these differences in the conceptualisation of PR.

Indications for physical restraint (according to consensus/tacit agreement of work teams).

| Nursing assistants (CCU where PR is FU) | Nursing assistants (CCU where PR is SU) | Doctors (mixed group) |

|---|---|---|

| Patient intubated and connected to mechanical ventilation | Patients with mechanical ventilation in the process of withdrawal from sedation to start early stages of weaning | Patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation in the process of withdrawal from sedation to start early stages of weaning |

| Patient withdrawing from sedation | ||

| Aggressive patient (self-and hetero-aggressive) | Patient momentarily agitated or disorientated when not responding to other types of restraint interventions | |

| Patient admitted due to attempted suicide | ||

| Patient with mental health problem |

PR: Physical Restraint; CCU: critical care units; SU: seldom used; FU: frequently used.

With regard to pharmacological restraint, even though it is considered in both clinical scenarios, in units where PR is FU the conceptualization is close to the idea of over-sedation (without clear awareness of the patient experiencing pain or anxiety), while in the units with SU it refers to the use of analgosedation to reduce the patient's perception of environmental stimuli (internal and external) that may negatively condition their recovery process.

In general, the nursing assistants understand that the purpose of using PR is to control some of the behavioural manifestations of patients. However, it should be noted that in the units where PR is FU, PR is attributed a capacity as resolution therapy, while in units with SU it is interpreted as a partial measure that only acquires meaning if used in an integrated manner with the other restraints (pharmacological, cognitive and emotional) when the latter 3, as a whole, are not fully effective (Table 2).

The nursing assistants from the CCU where PR is SU speak of cognitive restraint when they think of interventions such as information or education given to patients/family, which make it possible for the patient to implement cognitive coping strategies to deal with serious situations. Information, in this sense, provides the patient with a sense of control and safety (which results in better emotional and physical wellbeing).

FG_nursing assistants_SU: “[…] there are patients who have not had their situation explained to them […] PR, well, because it’s a preventive measure so […] I don’t have to keep an eye on things, I don’t have to stay in the cubicle or be constantly watching […] they’re used systematically in most cases […] sometimes you speak with the patients, you ask them to collaborate and they collaborate […] if you explain things a bit with them, patients do collaborate and they understand you”.

FG_nursing assistants_SU: “It should be valued very much if it’s really necessary […] you might be able to calm the patient down […] just being with them, explaining where they are […] it’s often because of pain”.

For its part, emotional restraint derives from care interventions such as emotional support or relaxation and distraction techniques that result, on the one hand, in making the patient switch off and, on the other, able to control their thoughts to modulate their emotions and behaviours (agitation).

FG_nursing assistants_SU: «[…] when I see someone like that, nervous, I have the habit of putting my hand on their forehead […]. One hand on their forehead and the other on their arm and they calm down. And they calm down for me.”

FG_nursing assistants_SU: “[…] there should be a protocol with music therapy […] they control pain, they control anxiety […]”.

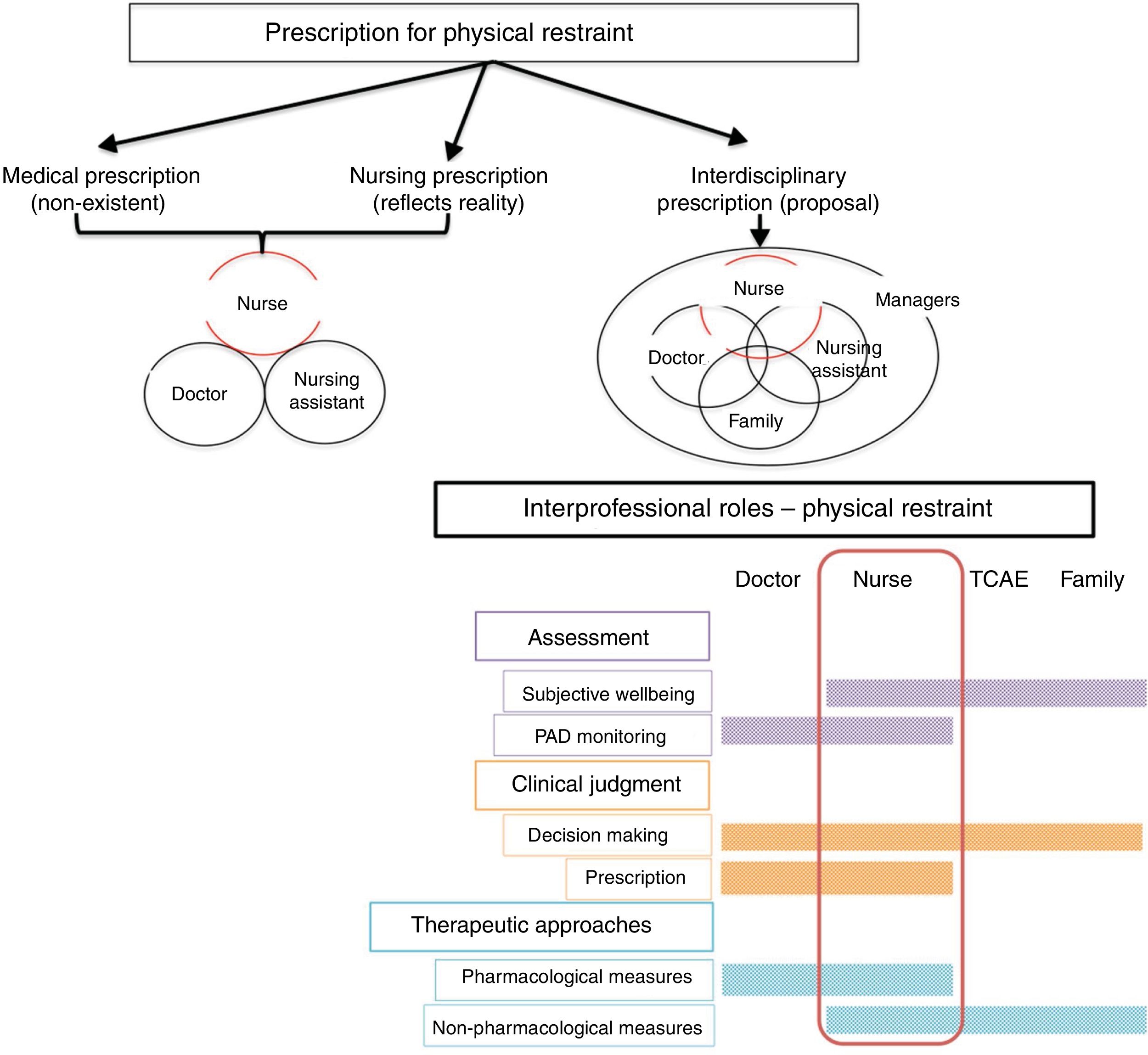

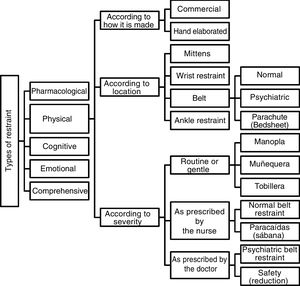

Professional responsibilities: prescription and recordingThe discourse of the professionals indicates remarkable invisibility of PR and haziness regarding prescription, and its use is generally not recorded.

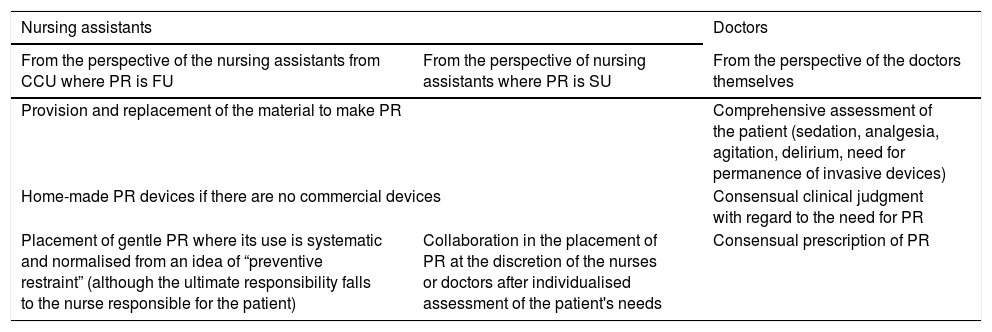

From the perspective of the nursing assistants, decision-making on the use of PR is supported by protocols or policies (explicit or implicit) on “preventive restraint”. So that any professional can take the initiative in using devices classified as routine or gentle (Fig. 3). However, the more severe the PR exercised by devices, the more decision-making shifts to other professional groups with more training and professional responsibility (Table 3). Most of the decision-making would fall to the nurse who, in addition to being considered ultimately responsible for the use of PR classified as gentle, indicates the use of belts and other handcrafted devices such as the “parachute”. Only in the case of psychiatric PR or the intervention of security personnel is the need for prescription by a doctor clearly identified. In the meantime, it is recognised that there is a lack of regulation or rules on prescription, which is reflected in the lack of recording of its use.

Self-perceived professional roles in relation to physical restraint.

| Nursing assistants | Doctors | |

|---|---|---|

| From the perspective of the nursing assistants from CCU where PR is FU | From the perspective of nursing assistants where PR is SU | From the perspective of the doctors themselves |

| Provision and replacement of the material to make PR | Comprehensive assessment of the patient (sedation, analgesia, agitation, delirium, need for permanence of invasive devices) | |

| Home-made PR devices if there are no commercial devices | Consensual clinical judgment with regard to the need for PR | |

| Placement of gentle PR where its use is systematic and normalised from an idea of “preventive restraint” (although the ultimate responsibility falls to the nurse responsible for the patient) | Collaboration in the placement of PR at the discretion of the nurses or doctors after individualised assessment of the patient's needs | Consensual prescription of PR |

PR: physical restraint; CCU: critical care unit; SU: seldom used; FU: frequently used.

FG_nursing assistants_FU: “The nurse’s judgement […] sometimes you see the situation and say — I’m going to get a wrist restraint—, you don’t need to be told, right? It’s obvious. But most of the time it’s up to the nurse […] but it’s a medical order. Where is this medical order? It never appears”.

FG_nursing assistants_FU: “And when we had them tied up and restrained, the anaesthetist came in and said, “who gave the order for them to be tied up?”. It’s just that… you know, a legal vacuum and that, and the responsibility of the nurse […] all the responsibility falls to the nurse […] and to the nursing assistants […]. They say ``yes, it’s there'', but as we have no responsibility…”.

The doctors, for their part, refer to the “trivialisation of restraint” normalising its use in daily care, trivialising or undervaluing the possible consequences of its use.

Mixed doctors’ FG: “[…] physical restraint is very trivialised […] the patient comes in and as he arrives […] they put on the wrist restraints […] it seems to be inherent to the care of any critical patient […] it isn’t given the importance it deserves, we need to rethink this problem, whether or not it’s really necessary”.

Given this trivialisation, they advocate judicious use guided by routine, multi-component and inter-professional assessment. According to the doctors’ discourse, clinical judgement and therapeutic planning should be joint and based on integrated and consensual protocols, thus leaving to one side decision-making centred exclusively on medical judgment and ending in ambiguity and uncertainty. This implies working with a single object of care (the patient), with common therapeutic objectives, under agreed outcome criteria, in an environment of communication and teamwork, and with a portfolio of interventions based on the notion of comprehensive restraint.

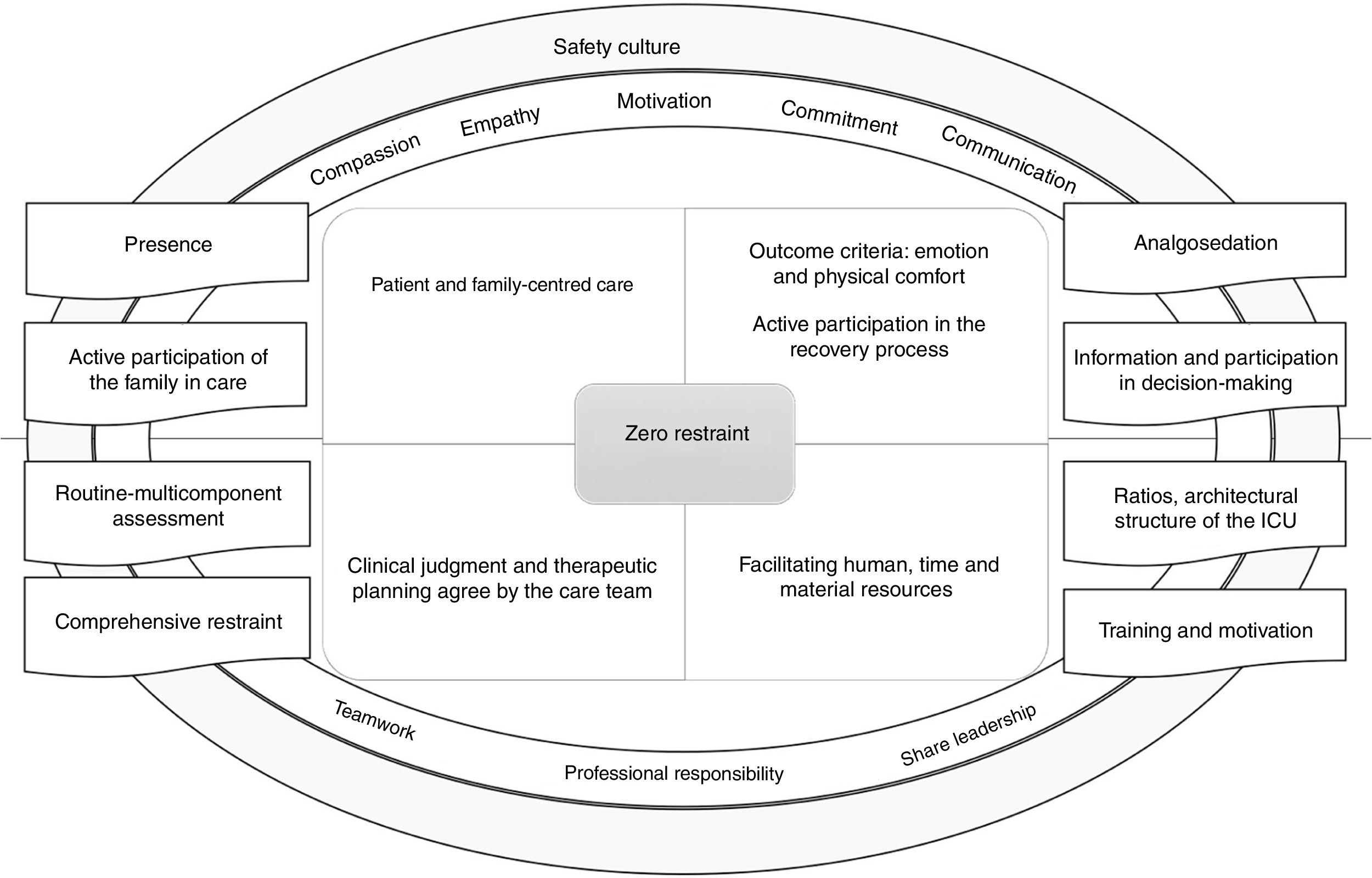

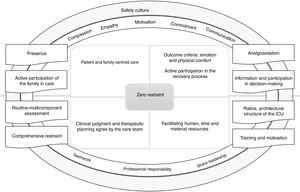

Zero restraintAn approach to working under the “zero restraint” paradigm appears in the discourse of the nursing assistants from CCU where PR is SU and of the doctors as natural and credible. This approach is based on 4 premises: patient and family-centred care, wellbeing -comfort and self-determination as outcome criteria, clinical judgement and planning consensual interdisciplinary care interventions, and provision of appropriate human and material resources (Table 4).

Factors favouring a physical restraint-free critical care unit.

| Empathic attitude | “It’s very negative to wake up from anaesthesia or sedation, not knowing where you are, you’re disorientated, you don’t know anyone, and on top of that you try to move and you can’t” FG_nursing assistants_SU |

| Compassionate therapeutic relationships | “But because we also didn’t bother with the issue, it’s that we don’t get involved, it’s better to be sitting at the computer, and I say, the dehumanisation that we have now, that’s it, we’re there at the computer, on the internet rather than being with the patient. And I’ve seen many patients, really, when they have a tube, they get very agitated too because we don’t try to make an effort to understand them, you can understand a patient when they have a tube and if you don’t look for other measures, well we don’t bother, honestly, you know? It’s really sad…». FG_nursing assistants_FU |

| Teamwork | “Information. Information, communication between… between health workers, between team members”. FG_nursing assistants_FU |

| Human resources adapted to the needs of the unit | “It’s that all this should be analysed and maybe, okay, they can’t give you more people, but maybe separate… well, look, since this gentleman is… - you look after this and I’ll deal with this, you know?” FG_nursing assistants_SU |

| Unit structure that allows patient monitoring and easy access | “And well, in my unit the good thing is that it’s diaphanous, there are no walls. So, I can see my patient continuously. That’s very good because it allows you to check your patient from a distance, and also because it gives you the peace of mind that you can see them, even though you might have to race”. FG_nursing assistants_FU |

| Health personnel training | “And that was the case until recently when you did the course and things changed a bit”. FG_nursing assistants_SU |

| Information given to the patient and their family | “But first we should explain to them, don’t get like that. Other ways of speaking to them, I think that…”. FG_nursing assistants_SU |

| Participating presence of the family | “Yes, but with immobilisation… if instead of therapeutic immobilisation… the other day this happened to us, instead of doing that, you took this and a family member came in and sat there on a chair taking the man’s hand, the thing was that he hadn’t existed all afternoon. I mean, there was a gentleman. You put in the thermometer, he had lunch, supper, he was got up from the chair, and there was no need to restrain him or anything.” FG_nursing assistants_SU |

Mixed doctors’ FG: “When are we going to be interested in it? Well, when everyone is aware that what is being done is not entirely correct, we may not reach 0% restraint, but we can definitely use less […] there has to be some kind of intention”.

Understanding the patient as the object of care implies taking patient safety as the axis of care, placing clinicians in the role of advocate. From this perspective achieving a subjective sense of wellbeing and comfort is seen as a priority. Some key elements to facilitate this wellbeing are linked to the presence of an effective reference and support figure. In the respondents’ discourse this figure is represented by the nurse, although it is considered that the family can contribute to providing emotional care with appropriate support from nurses.

On the other hand, correct analgosedation is essential for the patient to be in the best condition to work on self-control and consciously participate in the recovery process. Information provided to the patient and their family on clinical state and training in care interventions is essential to make decisions and participate in care, and thus gain a sense of control and self-esteem.

Mixed doctors’ group:"[…] until a few years ago it was thought that the intensive care patient had to be asleep and no […] he has to be awake, cooperative and pain-free and if you achieve that, well the tube will bother him a little, but well […]".

FG_nursing assistants_SU: "[…] if instead of putting therapeutic immobilisation in place […] a family member comes in and stays […] holding the man’s hand, the thing is he hadn’t existed all afternoon […] there was no need to tie him up or anything else".

None of this is possible, however, without a consensual interdisciplinary approach based on in-depth knowledge of the patient and joint decision-making. Routine multi-component assessment stands as key in this decision-making process, covering the monitoring of pain sedation-agitation, delirium and risk factors for its development and the necessity of continuing with invasive devices. This integrated and comprehensive interdisciplinary approach is reflected in the proposal for “comprehensive restraint” and would involve the creation of joint protocols. In this context, interpersonal communication (verbal and written recording) is essential, as is regulating the prescription of PR which, as it is ambiguous, generates invisibility and dilution of responsibilities.

FG_nursing assistant_SU: «[…] we’re all colleagues. […] I’ve never had problems with nurses when I explain my opinion to them, but speaking, you know, not disrespectfully ``no, it’s just that the nurse'', no, we play our part too”.

Mixed doctor’s FG: “[…] just like a nurse ``hey, we’re going for a blood sugar of 250, open the insulin line'', I should say to you ``hey, look there’s no way to keep this patient calm, I’m scared'', and we assess it together […] it’s verbalising a joint problem. […] we’re not at the foot of the bed 24 h a day […] it’s delegated to the nursing staff, nurses are competent, and many things that you’re not going to see in the 10 min you spend in each shift or hour […] it’s very odd how even assistants. […] Perhaps the key is to include the team a bit […] cohesion […] most issues start there, from a lack of a common objective and communication.”

Finally, in relation to human and material resources, different factors are identified as favouring the promotion of restraint-free CCUs (Table 4). For example, an adjusted nurse-patient ratio that facilitates the proximity and presence of the nurse at the bedside, pharmacological resources for elective analgosedation and team training in aspects of assessment and psycho-social-emotional interventions.

Finally, we return to a key directive from the professionals’ discourse, motivation. Motivation is needed that will drive the team towards a change of organisational culture and care, which implies, firstly, an awareness of how we are working and the purpose of our work, and secondly, planning a transition strategy with resources that favour a harmonious and integrative process based on communication, teamwork, shared leadership and compassionate, empathetic and committed care (Fig. 4).

Mixed doctors’ group: “Of course, no one thinks that maybe patients shouldn’t be tied up, perhaps we’re doing things wrong […] it’s also very difficult to break with… […] and I see it as a problem that is trivialised and it is cultural, so it must be changed […] it has to be brought back to the table, as a measure that is not trivial, routine, but something exceptional”.

DiscussionIn this study, the main findings revolve around the differences in the conceptualization of the concepts of safety and risk in CCUs where PR is frequently used versus seldom used, the types of restraint (physical and other) identified and the professional responsibilities that each entail. Finally, a theoretical but feasible work paradigm is identified of "zero restraint", proposed by both the doctors and the nursing assistants.

The use of PR in critical patients is now being tentatively but increasingly looked at, 1–11 but there seems no simple path. This is a complex and multifactorial issue with various actors involved that will require complex responses in order to really reduce its use.4,6,7,32–35 The results make it clear that the management of critical patient safety is possible through a policy of “zero restraint”, although we recognise some of the limitations of this study on this point. It would have been desirable to have had a profile of the FG participants, especially in the case of the nursing assistant group, who are more heterogeneous, but recruitment of volunteer professionals is difficult when working on such a complex issue. The discrepancy of approaches in relation to the current use of PR may have been influenced by the more likely voluntary participation of professional profiles more in favour of “zero restraint” and their discourse being more likely to be politically correct, and some participants might even have influenced others as the FGs developed. Furthermore, given the lack of reliable data in the literature and in the CCUs involved on the actual prevalence of PR use and factors modulating its use, the CCUs were stratified based on a non-validated self-prepared questionnaire, but agreed by the entire investigating team.

A zero restraint approach would be possible from a comprehensive and integrated, patient-centred approach, from a culture of safety focused on the perception of control and the emotion and physical wellbeing of the patient, and judicious and consensual decision-making.2,5,10,34,35 The need for a cultural change demanded by the respondents is also contemplated by other authors.1,2,5,10,35,48,49 In this regard, the main reason given by the professionals to justify the use of PR “the preservation of patient safety related to life support devices” must be modified by other meanings of the term “patient safety” from a more contemporary frame of reference. The conceptualisation of safety/risk from a more biological point of view is predominant in care models where the use of PR is common.4,6,35 With reference to the latter, Vía-Clavero et al. indicate that CCU professionals, in their case nurses, make a majority social construction of CCUs relating to physical safety.6 Nurses feel pressure from doctors to use PR and great pressure from the team in general to use PR.4,6 They feel that they are losing the “battle” and are using restraints on patients as a "lesser evil”,4,32 limiting patient safety to the prevention of adverse events and protecting themselves from blame, but with severe consequences in terms of moral suffering.6,17,50

In contrast, a comprehensive patient-centred approach with outcome criteria of wellbeing and control would be the alternative. This interpretation of the concept of safety is also described by other authors under the concept of “early Comfort using Analgesia, minimal Sedatives and maximal Humane care (eCash)”, which offers an excellent benchmark to guide the care of the critical patient from the prevention of pain, anxiety, agitation, delirium, immobilisation and promoting a situation of calm, comfort and cooperation.2 A key point to ensure this wellbeing and control is the meticulous management of analgosedation.2,3,8,11,21,51,52 Mehta et al.3 condense into 10 the basic strategies for managing pain, anxiety, distress and sleep disturbances in critically ill patients to optimise wellbeing, while avoiding over-sedation. With regard to non-pharmacological measures, the eCash proposal refers to therapeutic communication, information and training of the patient with respect to the recovery process and care interventions, time and space orientation, control of external stimuli (noise, light, manipulations…), facilitating night-time sleep, encouraging exercise and early mobilisation, cognitive stimulation, occupational therapy and involvement of families in the care process.2 To the interventions mentioned earlier Mehta et al.3 add relaxation techniques, music therapy, spiritual care, distraction techniques, animal therapy… The proposal for an anti-delirium approach in the Bundle ABCDEF of Ely et al.48 includes all of the above establishing clearly defined lines of action under the clear premise of an interdisciplinary approach.53,54

In the context of this necessarily interdisciplinary approach, nurses are key figures responsible for learning about the patient and his/her needs in depth to guide decision-making in analgesia management and the implementation of pharmacological (under nurse-guided protocols)53,55 and non-pharmacological measures.53,54 The nurse is considered by both the doctors and the assistants to be the figure who centralises information and serves to manage the patient’s needs by coordinating therapeutic interventions. This consensual definition of the nursing role is also brought up in a very similar way in relation to the maintenance of life support devices, with nurses being primarily responsible for the early identification of risk situations and potential complications to avoid treatment disruptions and ensure maximum patient safety during treatment in close collaboration and communication with the other members of the care team.56,57 Decision-making, however, does not seem to be a simple process, as mentioned by Goethals et al.32,33,50 It is a dynamic process whose central axis is the continuous assessment and evaluation of the patient. Nevertheless, two key principles are identified as the basis for judicious decision-making: reasoned and reflective process, focussed on patient safety.50

Discussing professional responsibilities necessarily leads the respondents to discuss the reality of prescribing PR. The current picture regarding PR prescribing in the CCUs in our environment seems to be the “non-existence of medical prescription” and the “routinisation” and “invisibility” of decision- making.4,6,9,10 In this regard, the proposal made previously by our working group to include PR prescribing as a field of nursing prescription would provide a response to a reality reflected in the respondents’ discourse: managing PR in CCUs falls to nurses.4 However, looking further towards a more current and desirable model of care, PR could be an example of interdisciplinary prescribing, in which only after the collection and analysis of comprehensive information and real balancing of pros and cons for the use/non-use of PR is a decision made. Thus, the prescription for the use of PR would have to be after unanimous and explicit agreement of all the professionals responsible for the patient’s care (Fig. 5). This approach is taken in the Belgian context where, even if the nurse has legal competence to prescribe PR, it is proposed that the decision should always be taken by the care teams jointly in terms of shared responsibility.56 This is termed inter-personal network as a forum for decision-making.33

When speaking of a judicious and consensual decision-making process, the fundamental pillars are the assessment of pain, anxiety, agitation and rest/sleep.3,4,11,52 Integrated multidimensional information guides the planning of care interventions at a pharmacological and non-pharmacological level, which in turn implies impeccable coordination between the different professionals. At this point, we must mention that other actors with a voice and operational capacity, the family, can exert major influence. Taking Haines’57 contributions as a reference, family participation can be understood gradually from transactional participation, through transitional participation, to transformational participation. The latter would cover the maximum achievable and would translate as true dialogue between clinicians and family as a result of continuous interaction guiding decision-making, leading to the design and implementation of pluralistic decision-making models.58 These models must evolve from the family-centred care model to a model of family engagement (empowered family actively included in decision-making from a perspective of commitment), where the role of the family unit takes a proactive stance in responding to their own values and needs.59 Moreover, the role of middle and senior managers should also be considered. With regard to the latter, the healthcare professionals highlight the passivity of managers with regard to the use of PR.6 These results seem consistent with the lack of involvement of managers detected in the discourse of both the doctors and the nursing assistants, as well as in the FG’s held with nurses previously. Institutional positioning and involvement could be key to achieving changes in clinical practice with the establishment of policies and strategic lines that generate a culture of restraint-free care and provide the structural resources (material and human) and knowledge necessary to accomplish it.33

ConclusionsThe situation in which we are immersed of extensive use of PR in critical patient care is currently under review. It is a complex phenomenon with various actors involved who jointly construct a care culture that determines the use of PR in each CCU.

Exploring the discourse underlying the experience makes it possible to become aware of beliefs, prejudices, myths and rituals, and thus understand the nature and basis of our actions and identify proposals for improvement.

The experience of the doctors and nursing assistants regarding PR management in CCU is conditioned by the safety culture, i.e., the concepts of safety and risk that they manage and what they understand by PR and the taxonomies built around it.

A patient-centred conceptualisation of safety and the notion of group responsibility points towards the possibility of reducing the use of PR. The lack of clarification of roles and professional competencies in relation to PR hinders consensual and joint communication and decision-making, which compromises its justified, reported and recorded use.

A PR-free model seems possible if elements such as safety are worked on from a holistic perspective; wellbeing is the objective and the patient is the focus of care. This model requires the involvement of all team members and consensual and integrated assignment of professional responsibilities and roles, where the nurse acts as the central reference figure. The nurse is responsible for centralising, integrating and transmitting to the care team the data describing the patient’s situation in relation to a comprehensive and multi-component assessment that results in judicious and consensual decision-making and that ensures patient safety. In this context the family should be considered and trained as care agents in relation to emotional-cognitive restraint and become empowered in CCUs to actively participate in making some decisions along with clinicians.

FundingThis study received funding from the Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda as the winner of the First Prize for the Best National Care Research Project (second edition-November 2016).

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to show our full appreciation to all of the people involved in the qualitative phase of the study (nurses, doctors and nursing assistants) who acted as respondents in the focus groups; without their sincerity, courage and involvement it would have been impossible to approach this complex reality of our ICUs.

Please cite this article as: Acevedo-Nuevo M, González-Gil MT, Solís-Muñoz M, Arias-Rivera S, Toraño-Olivera MJ, Carrasco Rodríguez-Rey LF, et al. La contención mecánica en unidades de cuidados críticos desde la experiencia de los médicos y técnicos en cuidados auxiliares de enfermería: buscando una lectura interdisciplinar. Enferm Intensiva. 2020;31:19–34.