Intensive care units are hostile places, which must be conditioned to the needs of patients and families, and therefore the factors that influence their satisfaction must be known.

ObjectiveTo update the knowledge on the satisfaction of the patients admitted to an adult intensive care unit and that of their family caregivers as described in the scientific literature.

MethodologyA systematized literature review was carried out in PubMed, Scopus, Cinahl and WOS databases. Search strategy: “Personal Satisfaction” and (patients or caregivers) and “Intensive Care Units”. Inclusion criteria: studies published between 2013-2018, population aged between 19-64 years, English and Spanish language.

Results760 studies were located and 15 were selected. The factors that increased satisfaction are: good communication with professionals (n = 5), the quality of care (n = 4), and the cleanliness and environment of the units (n = 2). The factors that produced dissatisfaction are: the infrastructure of the waiting room (n = 5), inadequate communication (n = 4), and the involvement of families and patients in decision-making (n = 4). Training of professionals (n = 5), inclusion of the family during the process of hospitalization (n = 2) and redesigning the waiting room (n = 2) are some of the suggestions for improvement.

ConclusionsFactors related to professionals, environment and cleanliness of the units are satisfaction-generating factors. Factors generating dissatisfaction related to poor infrastructure, a lack of involvement in decision-making and poor professional communication. Strategies to improve patient and family satisfaction relate to the organization, professionals, family members, and infrastructure and environment.

Las unidades de cuidados intensivos son lugares hostiles que se deben acondicionar a las necesidades de los pacientes y familiares, para esto se deben conocer los factores que influyen en la satisfacción de estos.

ObjetivoActualizar el conocimiento sobre la satisfacción de los pacientes ingresados en una Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos (UCI) de adultos y la de sus cuidadores familiares descritos en la literatura científica.

MetodologíaSe realizó una revisión bibliográfica sistematizada en las bases de datos PubMed, Scopus, Cinahl y WOS. Estrategia de búsqueda: «Personal Satisfaction» and (patients or caregivers) and «Intensive Care Units». Criterios de inclusión: Estudios publicados entre 2013-2018, población entre 19-64 años, idioma inglés y castellano.

ResultadosSe localizaron 760 estudios y se seleccionaron 15. Los factores que generan satisfacción son: Buena comunicación con los profesionales (n = 5), calidad de cuidados (n = 4) y limpieza y ambiente de la unidad (n = 2). Los factores que producen insatisfacción son: Infraestructura de las salas de espera (n = 5), inadecuada comunicación (n = 4) y la implicación de familiares y pacientes en la toma de decisiones (n = 4). Como estrategias de mejora encontramos el entrenamiento de los profesionales (n = 5), inclusión familiar durante el proceso (n = 2) y rediseño de las salas de espera (n = 2).

ConclusionesEntre los factores generadores de satisfacción hallamos los relacionados con los profesionales y con el ambiente y limpieza. Los que causan insatisfacción se relacionan con una mala infraestructura, falta de implicación en la toma de decisiones de pacientes y familiares y mala comunicación con los profesionales. Las estrategias para mejorar la satisfacción de los pacientes y familiares están relacionadas con la organización, los profesionales, los familiares y con la infraestructura y ambiente.

As technology has advanced, so have the techniques used to save patients' lives. Therefore, intensive care units (ICU) can be hostile and daunting places, for patients and their relatives. The focus of healthcare professionals often tends to be more medical than psychosocial, and emotional needs can be overlooked.1

Admission to ICU is not only stressful for patients (multitude of equipment, wires and technology, unfamiliar noises), but also for family members due to visiting policies and uncertainties regarding diagnosis and prognosis.2

To cope with this difficult stage, care must focus on the family unit, which includes patients and relatives. Many of the decisions in the patient care process have to be made by family members, and therefore family-centred care benefits patient care and decision making for family members and health professionals alike.1,2

Family caregivers are women and homemakers in most cases (85% of caregivers), in half they are daughters, and in almost 70% of cases they are over 65 years of age who may even need care themselves.3

Holanda et al.1 recognise the traditional value placed on family members as patient representatives. They propose the need to be aware of patients' perceptions to contrast them with those of their relatives, and establish how well the two coincide. They found a fair degree of agreement between the two groups, although the patients rated the ICU environment (noise, privacy, and lighting) worse, whereas the family members rated the waiting rooms worse.

A study on ICU patients’ perception suggested that the internal culture of the service is dominated by technical care and the organisation is centred around health professionals, and therefore there is a tendency towards dehumanised care.4

The degree of patient satisfaction is an indicator of quality of care.4 However, the questionnaires for measuring patient satisfaction in the ICU are not as well developed as those for family members. This is because patients are unable to communicate well for various reasons, such as orotracheal intubation, the severity of their clinical condition, or impaired level of consciousness.1

The Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units5 published a consensus document on quality indicators in the critically ill patient in 2017. In relation to the satisfaction dimension, these indicators were flexible visiting hours, satisfaction surveys on discharge from the service, adequacy of end-of-life care, adequate information from doctors and nurses to the family, decision-making instructions, informed consent, and limitation of life-sustaining treatment. These indicators are referred to in various studies when assessing patient and family satisfaction, although some were a cause of family dissatisfaction.1,2,6

On the other hand, Pardavila and Vivar2 highlight the importance of the nurse identifying the needs of family members and providing support and advice. They classify these needs into four types: 1. Cognitive needs: Information is the family's greatest need, but they perceive it to be unclear, provided infrequently and without consistency. 2. Emotional needs: This need is fundamental, as is the need to be close to the patient and the need to participate more in care. 3. Social needs: The flexible timetable is of note among the findings, adapted to the needs and responsibilities of the relatives; this flexibility and increased visiting hours also help the relatives to feel more involved in care. 4. Practical needs: This refers to the infrastructure and the environment and, in this regard, relatives are dissatisfied with the waiting rooms.2

Pérez et al.6 found that 94% of relatives reported that the waiting rooms were inadequate. The information received from professionals is also criticised, 89% of them considering it to be clear but brusque and tactless, and they are often given information late (90% of cases). Regarding visiting hours, the results indicate that relatives of conscious patients would like to have more visiting time, while relatives of intubated or sedated patients consider the times they are allowed to be adequate. Of those surveyed, 68% consider the time they are allowed adequate. And 68% of those surveyed feel the need to extend visiting hours to adjust better to their needs outside the hospital, such as work or family.

The project for humanising intensive care units proposes the training of professionals, greater presence of relatives, more flexible visiting hours and redesigning waiting rooms, among other proposals.7 There are other cases, such as the Hospital Virgen de Macarena (Seville) which has extended its visiting hours from three to five visits per day,8 and the redesigned ICU waiting rooms of the Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez (Huelva), based on satisfaction surveys carried out with relatives.9

The general objective of this study was to update knowledge on the satisfaction of patients admitted to the adult ICU and that of their family caregivers, as described in the scientific literature. The specific objectives were: 1. To describe the characteristics of the studies covering the factors that influence the satisfaction of adult ICU patients and that of their family caregivers. 2. To analyse the factors that influence the satisfaction of adult ICU patients and their family caregivers. 3. To determine the strategies used to improve the satisfaction of adult ICU patients and their family caregivers.

MethodologyTo meet our objectives, we conducted a systematised bibliographic review in the PubMed, Scopus, WOS, and CINAHL databases. The search strategy was: “Personal Satisfaction” and (patients or caregivers) and “Intensive Care Units”. We used the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) descriptors. The Boolean operators "and" and for intersection "OR" were used to link related terms.

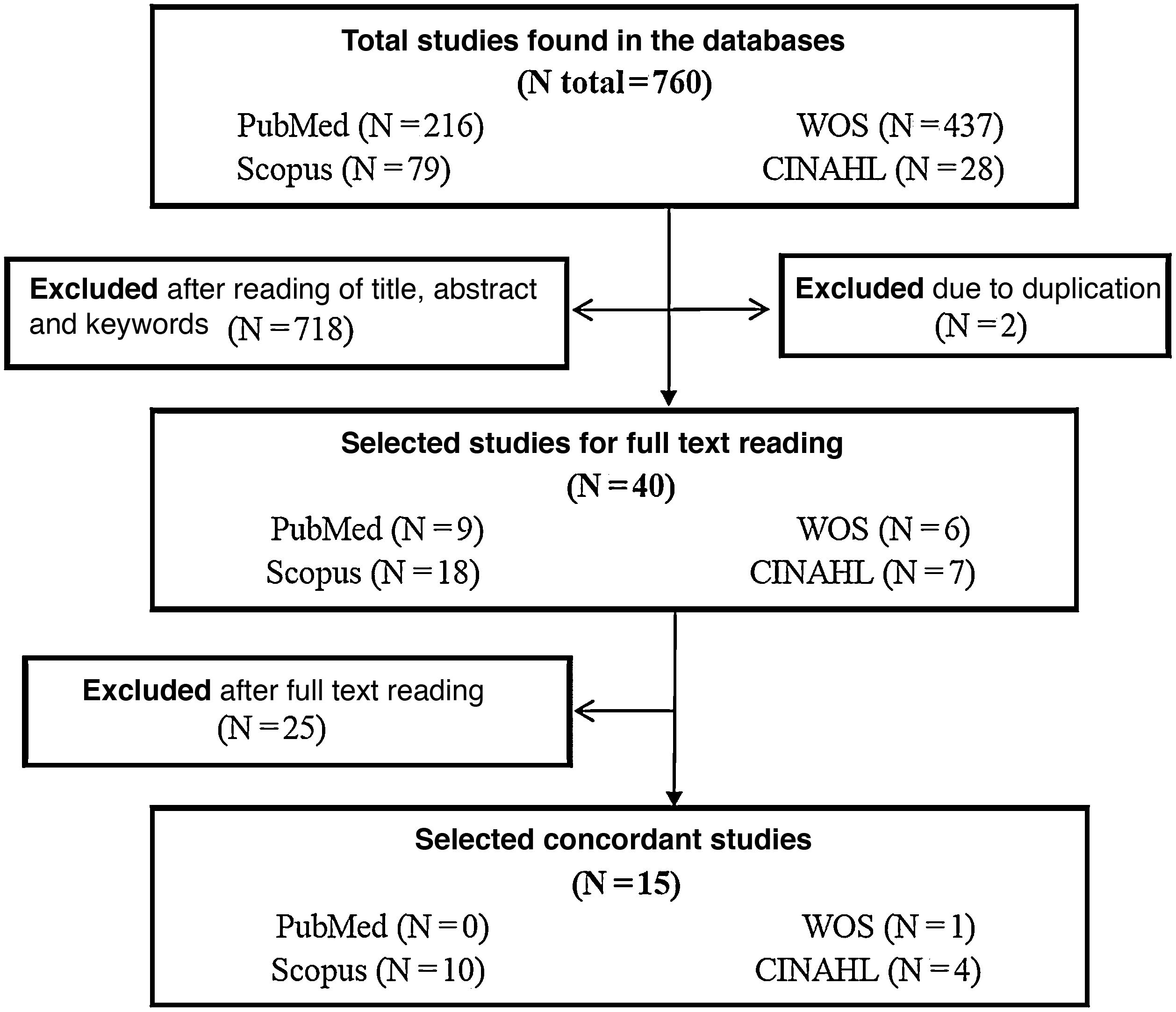

The selection process for the studies used three-stage screening. First, studies were located using the described search strategy, second, we conducted a reading of titles, abstracts, and keywords to assess the adequacy of the studies and duplicates were discarded, and third, we undertook a critical full text reading of the included studies, after which we selected the studies that matched the theme of study.

The inclusion criteria were research studies covering ICU patient satisfaction and published in scientific journals. The limits applied in the searches were studies published between 2013-2018, in English and Spanish. The exclusion criteria were studies comprising children under 19 years of age and those over 64 years of age.

A narrative synthesis was used to analyse the data. The data were summarised in a table with the characteristics of the studies, where the following data were collected: 1. Author/s and year. 2. Objective/s. 3. Study design and tools used. 4. Study period/country/sample. 5. Main findings.

ResultsStudy selection processThe initial search strategies identified a total of 760 studies, a final selection of 15 was made after the three screenings. Fig. 1 shows the process of study selection based on the objectives set out in a flow chart. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the studies.

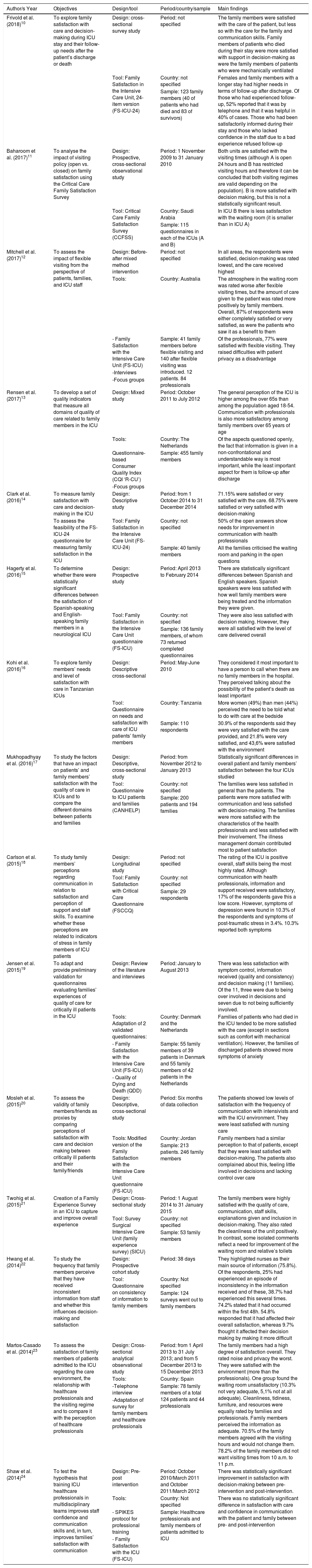

Characteristics of the studies selected.

| Author/s Year | Objectives | Design/tool | Period/country/sample | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frivold et al. (2018)10 | To explore family satisfaction with care and decision-making during ICU stay and their follow-up needs after the patient’s discharge or death | Design: cross-sectional survey study | Period: not specified | The family members were satisfied with the care of the patient, but less so with the care for the family and communication skills. Family members of patients who died during their stay were more satisfied with support in decision-making as were the family members of patients who were mechanically ventilated |

| Tool: Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit, 24-item version (FS-ICU-24) | Country: not specified | Females and family members with a longer stay had higher needs in terms of follow-up after discharge. Of those who had experienced follow-up, 52% reported that it was by telephone and that it was helpful in 40% of cases. Those who had been satisfactorily informed during their stay and those who lacked confidence in the staff due to a bad experience refused follow-up | ||

| Sample: 123 family members (40 of patients who had died and 83 of survivors) | ||||

| Baharoom et al. (2017)11 | To analyse the impact of visiting policy (open vs. closed) on family satisfaction using the Critical Care Family Satisfaction Survey | Design: Prospective, cross-sectional observational study | Period: 1 November 2009 to 31 January 2010 | Both units are satisfied with the visiting times (although A is open 24 hours and B has restricted visiting hours and therefore it can be concluded that both visiting regimes are valid depending on the population). B is more satisfied with decision making, but this is not a statistically significant result. |

| Tool: Critical Care Family Satisfaction Survey (CCFSS) | Country: Saudi Arabia | In ICU B there is less satisfaction with the waiting room (it is smaller than in ICU A) | ||

| Sample: 115 questionnaires in each of the ICUs (A and B) | ||||

| Mitchell et al. (2017)12 | To assess the impact of flexible visiting from the perspective of patients, families, and ICU staff | Design: Before-after mixed method intervention | Period: not specified | In all areas, the respondents were satisfied, decision-making was rated lowest, and the care received highest |

| Tools: | Country: Australia | The atmosphere in the waiting room was rated worse after flexible visiting times, but the amount of care given to the patient was rated more positively by family members. Overall, 87% of respondents were either completely satisfied or very satisfied, as were the patients who saw it as a benefit to them | ||

| - Family Satisfaction with the Intensive Care Unit (FS-ICU) | Sample: 41 family members before flexible visiting and 140 after flexible visiting was introduced. 12 patients. 84 professionals | Of the professionals, 77% were satisfied with flexible visiting. They raised difficulties with patient privacy as a disadvantage | ||

| -Interviews | ||||

| -Focus groups | ||||

| Rensen et al. (2017)13 | To develop a set of quality indicators that measure all domains of quality of care related to family members in the ICU | Design: Mixed study | Period: October 2011 to July 2012 | The general perception of the ICU is higher among the over 65s than among the population aged 18-54. Communication with professionals is also more satisfactory among family members over 65 years of age |

| Tools: | Country: The Netherlands | Of the aspects questioned openly, the fact that information is given in a non-confrontational and understandable way is most important, while the least important aspect for them is follow-up after discharge | ||

| Questionnaire-based Consumer Quality Index (CQI ‘R-CU’) | Sample: 455 family members | |||

| -Focus groups | ||||

| Clark et al. (2016)14 | To measure family satisfaction with care and decision-making in the ICU | Design: Descriptive study | Period: from 1 October 2014 to 31 December 2014 | 71.15% were satisfied or very satisfied with the care. 68.75% were satisfied or very satisfied with decision-making |

| To assess the feasibility of the FS-ICU-24 questionnaire for measuring family satisfaction in the ICU | Tool: Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit (FS-ICU-24) | Country: not specified | 50% of the open answers show needs for improvement in communication with health professionals | |

| Sample: 40 family members | All the families criticised the waiting room and parking in the open questions | |||

| Hagerty et al. (2016)15 | To determine whether there were statistically significant differences between the satisfaction of Spanish-speaking and English-speaking family members in a neurological ICU | Design: Prospective study | Period: April 2013 to February 2014 | There are statistically significant differences between Spanish and English speakers. Spanish speakers were less satisfied with how well family members were being treated and the information they were given. |

| Tool: Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit questionnaire (FS-ICU) | Country: not specified | They were also less satisfied with decision making. However, they were all satisfied with the level of care delivered overall | ||

| Sample: 136 family members, of whom 73 returned completed questionnaires | ||||

| Kohi et al. (2016)16 | To explore family members’ needs and level of satisfaction with care in Tanzanian ICUs | Design: Descriptive cross-sectional | Period: May-June 2010 | They considered it most important to have a person to call when there are no family members in the hospital. They perceived talking about the possibility of the patient’s death as least important |

| Tool: Questionnaire on needs and satisfaction with care of ICU patients’ family members | Country: Tanzania | More women (49%) than men (44%) perceived the need to be told what to do with care at the bedside | ||

| Sample: 110 respondents | 30.9% of the respondents said they were very satisfied with the care provided, and 21.8% were very satisfied, and 43,6% were satisfied with the environment | |||

| Mukhopadhyay et al. (2016)17 | To study the factors that have an impact on patients’ and family members’ satisfaction with the quality of care in ICUs and to compare the different domains between patients and families | Design: Descriptive, cross-sectional study | Period: from November 2012 to January 2013 | Statistically significant differences in overall patient and family members’ satisfaction between the four ICUs studied |

| Tool: Questionnaire to ICU patients and families (CANHELP) | Country: not specified | The families were less satisfied in general than the patients. The patients were more satisfied with communication and less satisfied with decision-making. The families were more satisfied with the characteristics of the health professionals and less satisfied with their involvement. The illness management domain contributed most to patient satisfaction | ||

| Sample: 200 patients and 194 families | ||||

| Carlson et al. (2015)18 | To study family members’ perceptions regarding communication in relation to satisfaction and perception of support and staff skills. To examine whether these perceptions are related to indicators of stress in family members of ICU patients | Design: Longitudinal study | Period: not specified | The rating of the ICU is positive overall, staff skills being the most highly rated. Although communication with health professionals, information and support received were satisfactory, 17% of the respondents gave this a low score. However, symptoms of depression were found in 10.3% of the respondents and symptoms of post-traumatic stress in 3.4%. 10.3% reported both symptoms |

| Tool: Family Satisfaction with Critical Care Questionnaire (FSCCQ) | Country: not specified | |||

| Sample: 29 respondents | ||||

| Jensen et al. (2015)19 | To adapt and provide preliminary validation for questionnaires evaluating families’ experiences of quality of care for critically ill patients in the ICU | Design: Review of the literature and interviews | Period: January to August 2013 | There was less satisfaction with symptom control, information received (quality and consistency) and decision making (11 families). Of the 11, three were due to being over involved in decisions and seven due to not being sufficiently involved. |

| Tools: Adaptation of 2 validated questionnaires: | Country: Denmark and the Netherlands | Families of patients who had died in the ICU tended to be more satisfied with the care (except in sections such as comfort with mechanical ventilation). However, the families of discharged patients showed more symptoms of anxiety | ||

| - Family Satisfaction with the Intensive Care Unit (FS-ICU) | Sample: 55 family members of 39 patients in Denmark and 55 family members of 42 patients in the Netherlands | |||

| - Quality of Dying and Death (QDD) | ||||

| Mosleh et al. (2015)20 | To assess the validity of family members/friends as proxies by comparing perceptions of satisfaction with care and decision making between critically ill patients and their family/friends | Design: Descriptive, cross-sectional study | Period: Six months of data collection | The patients showed low levels of satisfaction with the frequency of communication with intensivists and with the ICU environment. They were least satisfied with nursing care |

| Tools: Modified version of the Family Satisfaction with the Intensive Care Unit questionnaire (FS-ICU) | Country: Jordan | Family members had a similar perception to that of patients, except that they were least satisfied with decision-making. The patients also complained about this, feeling little involved in decisions and lacking control over care | ||

| Sample: 213 patients. 246 family members | ||||

| Twohig et al. (2015)21 | Creation of a Family Experience Survey in an ICU to capture and improve overall experience | Design: Cross-sectional study | Period: 1 August 2014 to 31 January 2015 | The family members were highly satisfied with the quality of care, communication, staff skills, explanations given and inclusion in decision-making. They also rated the cleanliness of the unit positively. In contrast, some isolated comments reflect a need for improvement of the waiting room and relative’s toilets |

| Tool: Survey Surgical Intensive Care Unit (family experience survey) (SICU) | Country: not specified | |||

| Sample: 53 family members | ||||

| Hwang et al. (2014)22 | To study the frequency that family members perceive that they have received inconsistent information from staff and whether this influences decision-making and satisfaction | Design: Prospective cohort study | Period: 38 days | They highlighted nurses as their main source of information (75.8%). Of the respondents, 25% had experienced an episode of inconsistency in the information received and of these, 38.7% had experienced this several times. 74.2% stated that it had occurred within the first 48h. 54.8% responded that it had affected their overall satisfaction, whereas 9.7% thought it affected their decision making by making it more difficult |

| Tool: Questionnaire on consistency of information to family members | Country: Not specified | |||

| Sample: 124 surveys went out to family members | ||||

| Martos-Casado et al. (2014)23 | To assess the satisfaction of family members of patients admitted to the ICU regarding the care environment, the relationship with healthcare professionals and the visiting regime and to compare it with the perception of healthcare professionals | Design: Cross-sectional analytical observational study | Period: from 1 April 2013 to 31 July 2013; and from 5 December 2013 to 15 December 2013 | The family members had a high degree of satisfaction overall. They rated noise and privacy the worst. They were satisfied with the environment (more than the professionals). One group found the waiting room unsatisfactory (10.3% not very adequate, 5,1% not at all adequate). Cleanliness, tidiness, furniture, and resources were equally rated by families and professionals. Family members perceived the information as adequate. 70.5% of the family members agreed with the visiting hours and would not change them. 78.2% of the family members did not want visiting times from 10 a.m. to 11 p.m. |

| Tools: | Country: Spain | |||

| -Telephone interview | Sample: 78 family members of a total 124 patients and 44 professionals | |||

| -Adaptation of survey for family members and healthcare professionals | ||||

| Shaw et al. (2014)24 | To test the hypothesis that training ICU healthcare professionals in multidisciplinary teams improves staff confidence and communication skills and, in turn, improves families’ satisfaction with communication | Design: Pre-post intervention | Period: October 2010/March 2011 and October 2011/March 2012 | There was statistically significant improvement in satisfaction with decision-making between pre-intervention and post-intervention. |

| Tools: | Country: Not specified | There was no statistically significant difference in satisfaction with care and confidence in communication with the patient and family between pre- and post-intervention | ||

| - SPIKES protocol for professional training | Sample: Healthcare professionals and family members of patients admitted to ICU | |||

| - Family Satisfaction with the ICU (FS-ICU) |

CANHELP: Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project questionnaires. CCFSS: Critical Care Family Satisfaction. CQI ‘R-ICU’: Questionnaire-based Consumer Quality Index ‘Relatives in Intensive Care Unit’. FS-ICU: Family Satisfaction with the Intensive Care Unit. FSCCQ: Family Satisfaction with Critical Care Questionnaire. FS-ICU-24: Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit, 24-item version. QDD: Quality of Dying and Death. SICU: Surgical Intensive Care Unit (family experience survey). SPIKES: Setup, Perception, Invitation, Knowledge, Emotions, Strategy.

In terms of year of publication, one study was published 2018,10 three in 2017,11–13 four in 2016,14–17 four in 2015,18–21 and three in 2014.22–24 In terms of language, one study is published in Spanish,23 while the remaining fourteen are in English.10,24 Regarding the design of the studies, two are mixed studies (qualitative and quantitative)12,13 and 13 are quantitative.10,11,14–24 In terms of tools, five studies used the family satisfaction with the ICU questionnaire (FS-ICU)12,15,19,20,24 and two the adapted questionnaire (FS-ICU-24).10,14 Eight of the studies do not specify where they were conducted.10,14,15,17,18,21,22,24 The countries of the remaining seven are as follows: Denmark and the Netherlands,19 the Netherlands,13 Saudi Arabia,11 Jordan,20 Tanzania,16 Australia,12 and Spain.23 Regarding satisfaction, 11 studies analyse the satisfaction of ICU patients’ family members,10,11,13–15,18,19,21–24 and four studies examine the satisfaction of family members and patients.12,16,17,20

Factors influencing satisfactionIn terms of factors that may influence satisfaction, two studies compared the satisfaction of relatives of patients who died during their stay in the ICU and of those who were discharged.10,19 Quality of care was identified as satisfactory for both relatives and patients in four of the 15 studies.12,14,16,21 Five studies report that effective communication is a source of satisfaction for relatives and patients.13,17,18,21,23 Regarding flexible or restricted hours, three studies refer to flexible or restricted hours.11,12,23 Two studies cover the environment and cleanliness of the unit.21,23 We found one study on the skills of health professional.21 One study covers the factors that generate patient and family satisfaction in ICU.17

Regarding factors that may cause dissatisfaction, four studies mention the infrastructure and atmosphere of the waiting room as a factor that negatively affects the overall satisfaction of relatives.11,12,14,21,23 Four studies describe encouraging the involvement of relatives and patients in the decision-making process as an aspect that could be improved.12,17,19,20 Four studies emphasise the need to improve communication between relatives and patients and healthcare professionals.14,19,20,22 Inconsistent information received from professionals was reported as unsatisfactory in one study.22

Improvement strategiesDifferent strategies for improvement are proposed in the studies, and some include several strategies. Five mention the desirability of improving communication between health professionals and relatives and patients.10,12,21,22,24 Five studies highlight the desirability of improving different aspects that influence satisfaction, such as training professionals in communication skills, emotional support, conflict management and coping.10,14,20,23,24 Improvements in the infrastructures of ICUs as well as waiting rooms are proposed in five.12,14,20,21,23 The involvement of family members and patients in decision-making is described as an improvement in three.10,20,24 Two studies report the involvement of the family in the care process as a strategy.10,12 The following are proposed as improvements in other studies: extending spiritual and cultural care to the family,21 improving the organisation of the unit,22 providing support between professionals for flexible visits,12 the consistent assignment of a professional to each patient and family support by a multidisciplinary team,14 and telephone follow-up after discharge.10

DiscussionCharacteristics of the studiesIn more than half the studies, the family members group primarily comprises women aged between 35 and 50 years, generally the patients’ partners or daughters.12,13,16–18,20,22,23 This is consistent with the results obtained from other studies, which show that women are primary caregivers.3 In this review, we found no studies dealing exclusively with the satisfaction of ICU patients, which may be due to communication difficulties.1

Factors influencing satisfactionRegarding the factors that generate satisfaction among ICU patients and relatives, Mukhopadhyay et al.17 report that for patients, the first factor is appropriate management of their disease, and for families, the characteristics of the healthcare professionals, whereas the relationship with the doctors comes second for both groups.

Frivold et al.10 and Jensen et al.19 report greater satisfaction in the family members of patients who died during their stay in the ICU than in those discharged; the relatives of the latter tending to be more anxious. However, in the study by Holanda et al.,1 no significant differences were found in the degree of satisfaction between the relatives of deceased patients and of survivors.

The study by Carlson et al.18 suggests that communication with the family should be improved to reduce the symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress that they presented. On the other hand, Rensen et al.,13 report greater satisfaction with communication and other aspects in general among the population over 65 years of age, than among younger people. Another study not included in this review states that involving family members in the care of critically ill patients reduces their anxiety and is a source of satisfaction for patients and relatives alike.6

Regarding communication and information received by professionals, the study by Mosleh et al.,20 comparing the perceptions of satisfaction of relatives and patients in critical care units, obtains fairly comparable results, although patients are less satisfied with the care provided and relatives are less satisfied with decision-making. They also suggest that the limited time professionals have to deliver care to patients may contribute to their not including family members in the care process.20 In this regard, a study outside this review argues that effective communication between relatives and healthcare professionals is necessary to improve the family's understanding, allowing them to express their concerns and thus, reduce their emotional burden. However, staff require adequate time for patient care.25

In the study by Hwang et al.,22 just over half the relatives were involved in episodes that affected their overall satisfaction, a third of the participants described nurses as the main source of information and a quarter reported inconsistencies in the information provided to them. Another study states that the role of the nurse needs to be humanised and reflective, with critical patients rating effective communication and kind treatment as satisfactory.4

Regarding infrastructure and environment, different authors state that ICUs are not prepared to preserve the privacy and intimacy of the patient,12,23 they complain about relatives’ toilets,21 and the noise in the unit,23 which gives rise to an unsatisfactory environment.20 This review found no study that provides a positive assessment of waiting rooms. Several studies suggest that waiting rooms should be improved and redesigned,11,12,14,20,21,23 which is consistent with other studies.1,6

Regarding visiting hours, although SEMICYUC5 recommends flexible or “open door” policies as an advantage and a necessity for the family, the results obtained in this review do not show a clear tendency towards one over the other. Mitchell et al.12 report an increase in family members' satisfaction with the care provided when flexible visiting is implemented, and that the family provides significant support to nurses and values the care more highly. They also report that flexible hours in the ICU encourage closeness and family support, communication and critical substitute decision making.12 Other studies suggest that open visiting hours are beneficial for patients and their relatives, as they help to reduce stress, and patients benefit from having their relatives close by, as they can be more involved in their care.2,26

Mitchell et al.12 report that, by moving from a restrictive to a flexible schedule, the atmosphere became worse in the waiting room.12 Other studies report that family members give the worst rating to the waiting room.1,2,6

In relation to visiting times, Baharoom et al.,11 when comparing satisfaction with an ICU with flexible versus another with restricted visiting, conclude that users of both units are satisfied with both, with no statistically significant differences. They question whether the change in ICU visiting policies would be perceived positively or negatively.11 In the study by Martos-Casado et al.,23 almost a third of the relatives were satisfied with the visiting hours and when offered longer and uninterrupted visiting (from 10 am to 11 pm), almost 80% were not in favour of the change. They conclude that families are happy with the established restricted times.23

Strategies for improvementFrivold et al.10 propose patient follow-up after hospital discharge as a strategy to improve the satisfaction of ICU patients and relatives. They report that women and relatives of patients who have had a long stay demand this follow-up most although they note that only 40% of the families who received discharge follow-up considered it useful.10 In another study, relatives rated follow-up after discharge as a factor that least influenced satisfaction, rating clear, understandable information without contradictions as the most relevant.13 The follow-up service for ICU patients on the ward was rated very high.1

Shaw et al.24 suggest as a strategy for improvement, training for professionals to improve confidence and communication skills with relatives and ICU patients. Family members reported that it improved their participation in decision-making. The authors argue that efforts should focus on improving communication between professionals and family members, rather than on follow-up after discharge.24 In this regard, Kohi et al.16 state that it is important to improve communication regarding the care process with relatives and that women are most involved in this process. Other authors suggest that adequate systematic information that meets the needs of the relatives of critically ill patients, and adequate training for professionals are very important.2

Another strategy for improvement is to implement a care model centred on the patient and family, in which they participate in the care process and in shared decision-making.12,20,21 In this regard, some authors argue that the care unit should be recognised as a system where families and patients are interconnected and influenced.2,26 Likewise, the manual of quality indicators in critically ill patients5 of the Spanish Society of Critical Intensive Care Medicine and Coronary Units, in the satisfaction dimension of the survey of perceived quality on discharge from the intensive care service, states that patient- and family-centred care is one of the main objectives of care.

In terms of infrastructure and environment, strategies focus, on the one hand, on improving the ICU so that there is less noise, so that patients and families can have greater privacy and intimacy, and also so that toilet facilities are adapted to the needs of family members.12,20,21,23 It is also suggested that waiting rooms should be designed based on the needs of relatives.14,20,21,23

As a strategy for improvement regarding the organisation of the unit, daily meetings of the multidisciplinary team were held to prepare the most frequent questions from family members, to provide consistent answers and avoid incoherence and inconsistencies in information.22 Another study describes the consistent assignment of a professional to each patient and support for families by a multidisciplinary team as strategies for improving satisfaction.14

With regard to visiting hours, support among more and less experienced professionals for the appropriate implementation of flexible visiting times is raised as a strategy for improvement.12 Other authors state that visiting hours should be adapted to the needs of ICU patients, and therefore must be tailored to the needs of the individual.6 Open visiting also has beneficial effects for relatives, and thus increases their satisfaction.26

Limitations of the reviewThe heterogeneity of the studies is a limitation of this review, which we have tried to overcome by treating the data in a rigorous and methodical way,27 another is the impossibility of retrieving all the information on the subject of the study, and further limitation is that we did not conduct an analysis of the quality of the studies.

Proposals for future researchFurther research on the factors influencing the satisfaction not only of patients and relatives, but also of health professionals would be desirable. To compare agreement between the opinions of ICU patients and those of their relatives and to establish whether the latter can be considered appropriate representatives. The impact of the improvements implemented in both ICUs and waiting rooms should also be analysed to determine whether the measures taken are effective.

ConclusionsPatient and family caregiver satisfaction in the adult ICU is linked to the infrastructure and environment of the ICU and the waiting room; to communication between health professionals, patients, and families; to family support and to shared decision-making between family members and patients as a model of care. It is also influenced by the training and education of healthcare professionals, their job stability, and the organisation of the service through teamwork and regular meetings.

What is known? What does this paper contribute?

ICUs are hostile and stressful places, both for the patient and their family caregivers. There are few studies that analyse patient satisfaction. Therefore, in this study we have investigated satisfaction among both groups and proposed strategies for improvement.

Implications of the study

We present factors generating satisfaction and dissatisfaction, as well as areas for improvement related to the organisation, health professionals, relatives, infrastructure, and environment. This knowledge can be used in clinical management for decision-making since user satisfaction is an indicator of quality of care.

No funding was received for this work.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Guerra-Martín MD, González-Fernández P. Satisfacción de pacientes y cuidadores familiares en unidades de cuidados intensivos de adultos: revisión de la literatura. Enferm Intensiva. 2021;32:207–219.