To evaluate the level of knowledge and the degree of satisfaction obtained through continuous training in simulation-debriefing methods as a learning tool in the care of cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA).

MethodA quasi-experimental study. Evaluation by ad hoc questionnaire (pre and post, and reassessment at 4 months) to all professionals (physicians and nurses) who passed any of the 6 editions of the course: ‘Simulation of situations of cardiopulmonary arrest or peri-arrest in hospitalisation units’. Descriptive and inferential statistics.

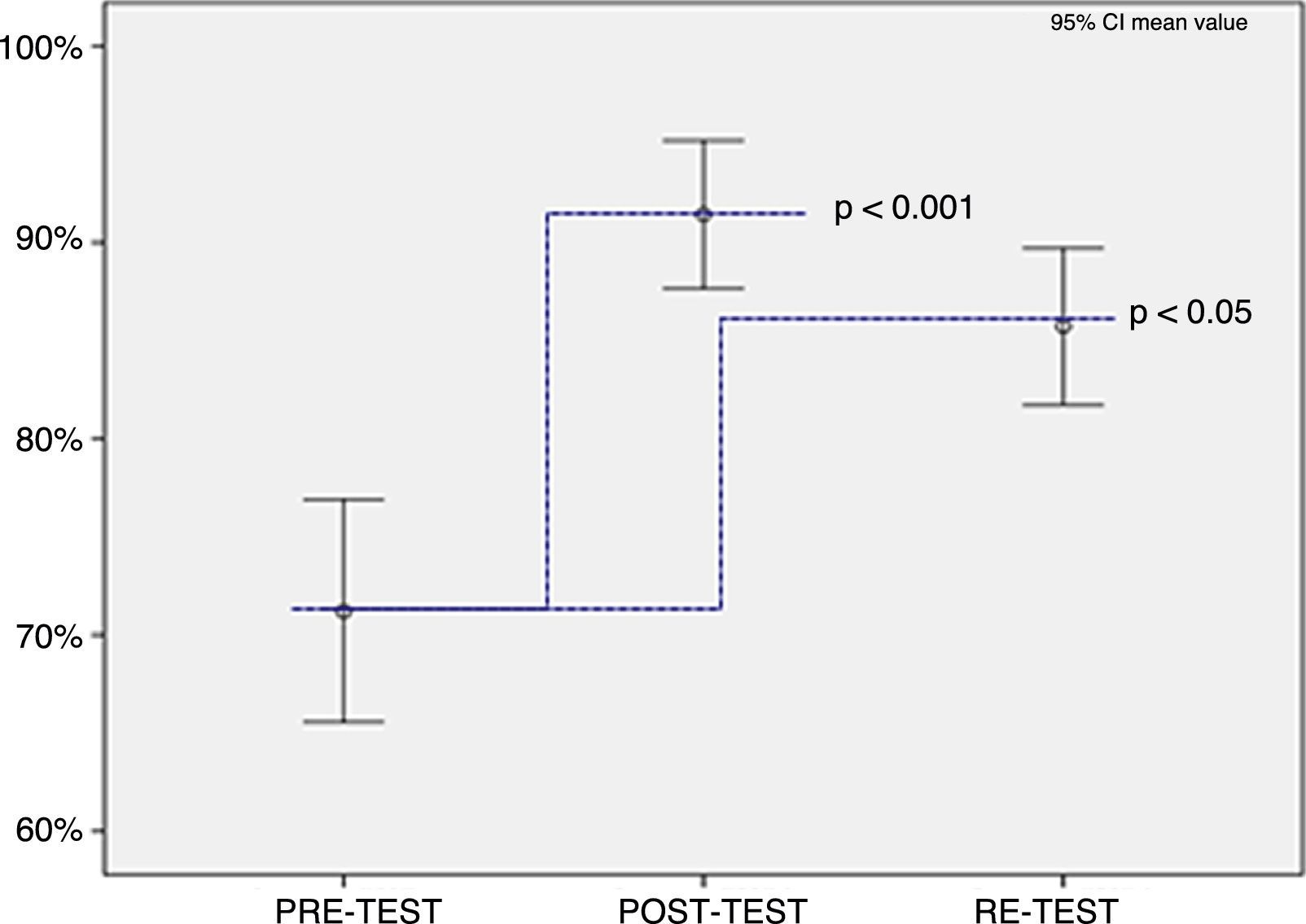

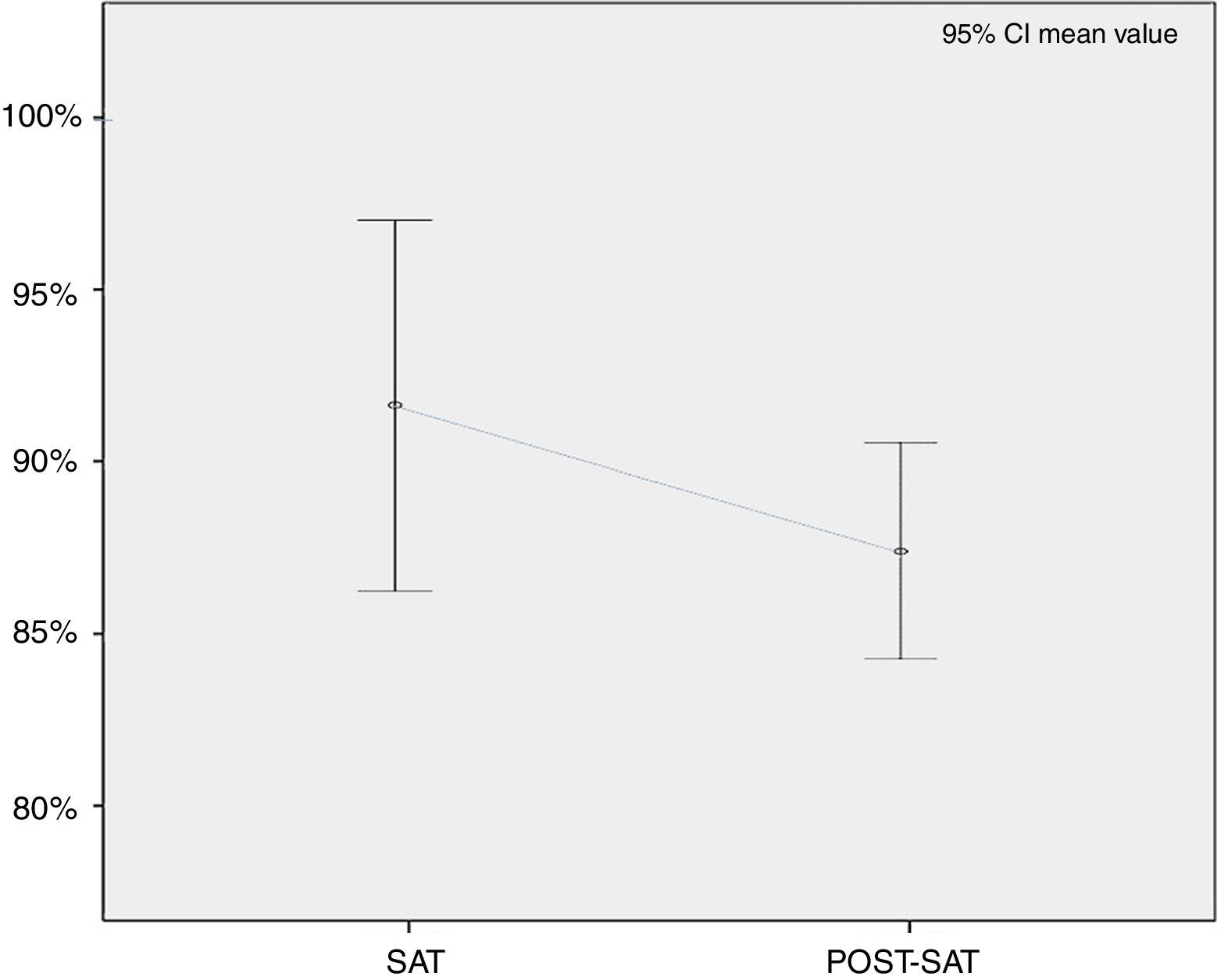

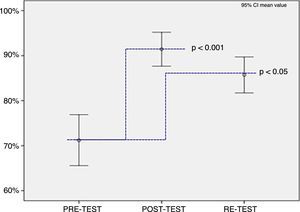

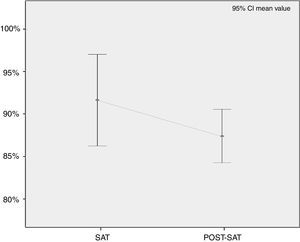

Results133 participants, 16 physicians, and 117 nurses. Before the course started, the level of knowledge was 78.5%, at the end of training it was 94.6% (p<.001), and after 4 months, it was 88% (p<.05). The satisfaction achieved was 91.8% at the end of the course, and subsequently 88.4%; this was significant (p<.05) among the younger professionals, with less experience and with a temporary contract. Eighty one point two percent of the participants expressed that they changed the way they acted during a cardiopulmonary arrest.

ConclusionsContinuous education in CPA, performed through simulation-debriefing, is consolidated in our field as an effective tool to acquire a suitable level of knowledge that lasts over time. The level of satisfaction achieved was high since this method of learning meets the expectations of the professionals and resembles real care practice.

Evaluar el nivel de conocimiento y el grado de satisfacción conseguidos mediante la formación continuada en la modalidad de simulación-debriefing como herramienta de aprendizaje en la atención a la parada cardiorrespiratoria (PCR).

MétodoEstudio cuasiexperimental. Evaluación por cuestionario ad hoc (pre y post, y reevaluación a los 4 meses) a todos los profesionales (médicos y enfermeras) que aprobaron alguna de las 6 ediciones del curso: «Simulación de situaciones de parada o periparada en las unidades de hospitalización». Estadística descriptiva e inferencial.

ResultadosParticiparon 133 profesionales; 16 médicos y 117 enfermeras. Al inicio, el nivel de conocimiento fue del 78,5%, al finalizar la formación alcanzó el 94,6% (p<0,001), y al cabo de 4 meses se situó en el 88% (p<0,05). La satisfacción alcanzada fue del 91,8% al final del curso, y posteriormente del 88,4%, siendo significativa (p<0,05) entre los profesionales de menor edad, los de menor experiencia y eventuales. Referente al impacto (4 meses después), el 81,2% de los participantes expresaron que cambiaron su manera de actuar ante una PCR.

ConclusionesLa formación continuada en PCR, realizada a través de la simulación-debriefing, se consolida en nuestro ámbito como una herramienta eficaz para adquirir un nivel de conocimiento adecuado y perdurable a lo largo del tiempo. El grado de satisfacción conseguido ha sido elevado, ya que este método de aprendizaje cumple las expectativas del profesional y se asemeja a la práctica asistencial real.

Clinical healthcare education has traditionally been determined by the availability of real or simulation patients in clinical practice, so that the student may acquire some experience in professional practice. However, continuous professional training in critical emergency situations supports the use of techniques and systems with possible risks for the participants and for the people (patients) who serve as models for practice. As a result of this, a different type of “simulation” without technology, which is based on virtual scenarios and the application of the “debriefing” technique, has arisen. This teaching method is considered capable of solving the limitations of conventional methodology with faster, long-lasting acquisition of individual professional skills whilst team working.

Implications of the studyIn our case, the workshop “simulation of situations of cardiopulmonary arrest or peri-arrest in hospitalisation units” (CPA simulation-debriefing) is presented as a teaching/learning model or method which adapts to the organisation's needs and the professional expectations of professionals (it resembles real care practice and enhances satisfaction) and pre-emptively serves to acquire the established learning objectives (improving skills and/or knowledge), transference (implementation in healthcare practice) and impact or repercussion (achieves higher standards of organisational quality). Moreover, simulation with debriefing in critical situations is a useful tool for nursing practice teaching, management and research because it provides new teamwork opportunities and actions which need exploring and validating.

Continuous professional training is defined as “an active, permanent teaching/learning process which health professionals have the right to and are obliged to follow. It begins when degree or specialist studies end and is aimed at updating and improving their knowledge, skills, and attitudes towards scientific and technological development as well as the demands and needs of society and the system itself”.1

Thanks to continuous professional training professionals are able to acquire knowledge which induces them to gradually change the way they act, as a result of training experience.2 For this reason, continuous training must comply with a series of basic requirements or premises which determine use, such as3:

- •

Adaptation to the organisation's need and the professionals’ expectations.

- •

Implementation with the highest quality standards.

- •

Compliance with rigorous planning.

- •

Achievement of the intended objectives.

Increase in continuous professional training activities in the healthcare area has not always been complemented by the necessary assessment of results to determine whether the learning process is genuinely useful for changing or modifying professional practice. This is due to the fact that it is based on traditional teaching systems. Clinical teaching in the healthcare environment has always been determined by the availability of real or simulated patients (standard patients) for practice, so that the student may acquire some experience in professional practice. However, this involves the use of techniques and systems with possible risks attached for the participants and the people (patients) who serve as models for practice.4,5

In the light of this, “simulation” emerges as a teaching and pedagogical tool which is able to surpass the limitations of conventional methodology,6 since it may be used in undergraduate, post-graduate, specialised and continuous professional training, with individual professional skill acquisition enhanced by team work.7

According to the Royal Academy of Spanish Language dictionary, the term “simulates” means8: “to represent something by pretending or imitating what it is not”. For the Centre for Medical Simulation (Cambridge, Massachusetts) “simulation” is defined as9 “a situation or setting which has been created to allow people to experience the representation of a real event, aimed at practising, learning, assessment, testing or acquiring knowledge of systems or human actions”.

Simulation is no replacement for reality, but it is much closer than any other mode of learning.7 this technique aims at extending and substituting real experiences for directed ones, which reproduce the major, essential aspects of a real situation that may be an everyday one, or an unusual, infrequent but nevertheless real situation.6

The development of simulation techniques is firstly linked to the development of computing technology (the need for the creation of virtual settings) and secondly to the need for reducing adverse risks associated with the activity.6 The development of this technology also leads to a major advance of teaching methods with simulation, among which the debriefing (simulation-debriefing) technique is noted for its innovative approach. This method of learning is based on discussion in which participants and observers analyse the actions and experiences gained during simulation, measured by guided reflection of the teacher or instructor, searching for ways in which to optimise outcome.10–12

Similarly to any other continuous professional learning method, learning based on simulation-debriefing must conform to assessment to measure the level of satisfaction with the activity performed and preferably comply with an assessment which includes learning (assimilation of acquired knowledge), transference (putting knowledge into real care practice), and impact or repercussion (changes in practice on an organisational level).13–15

The aim of our study was to evaluate the level of knowledge and satisfaction from continuous education in the simulation with debriefing model as a learning tool on cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA).

MethodDesign. A quasi experimental study was carried out in three phases: pre-evaluation, post-evaluation and re-evaluation.

Area. The study was wholly developed in the simulation classrooms of a public health university hospital complex (UHC), of the Galician health service (Sergas). The research period was from September 2013 to May 2014.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria: the study population comprised all professionals (doctors and nurses) who had obtained the classification of “apt” (inclusion criteria) in some of the 6 editions of the course-workshop “simulation of cardiopulmonary arrest or peri-arrest situations in hospital units” (hereinafter called “CPA simulation”). i.e. those students who had passed the right to be certified for the course, who passed after several theoretical and practical exams with 70% or above of the established maximum and who had attended 95% of the classes. Those who did not obtain this qualification or who did not wish to participate in the study were excluded.

Determination of the sample size. 133 subjects were studied which resulted in the characteristics on knowledge and satisfaction were able to be determined with a ±8% precision and 95% dependability, on the assumption of 5% possible losses.

Questionnaire design and variables selection. As no validated questionnaire on this subject was found in the literature, an ad hoc questionnaire was designed to measure the level of knowledge in the pre-post and re-evaluation (TEST questionnaire) phases. It contained 6 questions with a single true response, awarding one point for each right answer and zero points for wrong answers. The satisfaction level was assessed at the end of the course with an ad hoc questionnaire which is used in a standardised way by the Continuous Training Unit of the UHC in all course taught, and this consisted of a Likert type 6-question questionnaire with scores from 1 to 5 where 1 was “dissatisfied” and 5 “highly satisfied” (SAT questionnaire). Finally, to assess the degree of satisfaction and impact for long-term improvement, an ad hoc questionnaire was designed (POST-SAT questionnaire) which included 10 questions, with one point given to the responses when they were correct with regards to satisfaction and 0 points when not.

All the questionnaires designed for the study were based on the latest references and were subject to previous pilot studies (15 instruction experts licensed in simulation teaching collaborated), and from them the most relevant questions were selected, erroneous items were identified, together with possible problems of legality. Other demographic and professional data were also collected (age, professional status, professional experience and employment situation) and an open-ended question was included for comments or suggestions.

Research training and teaching experience. The “simulation of cardiopulmonary arrest or peri-arrest in hospitalisation units” (CPA) course-workshop was imparted by 15 medical and nursing professionals from the Emergency and ICU services. They were all licensed as instructors of basic and advanced life support by the American Heart Association (AHA) and the Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine (SEMES). 4 teachers were licensed as instructors in Advanced Clinical Simulation by the Institute for Medical Simulation (IMS). The others held the title of “Teacher trainer in simulation”, endorsed by the Health Knowledge Agency (ACIS) of Sergas’ own accrediting authority.

A schedule of 6 editions of the course-workshop was established, aimed at area specialists and hospitalisation nurses. Lecture time consisted of 9.5 hours theory and practice (1.8 CPT credits) in a face-to-face environment for 2 consecutive days. During the course-workshop 6 virtual “simulation and debriefing” sessions took place on ventricular and supraventricular tachycardias (several cases with and without a pulse), non-shockable rhythms, (VF and VT with no pulses) and non-shockable and blocks. 5 groups of 4 people were established to carry out simulation. All the courses took place in the hospital simulation rooms used for teaching. The maximum number of places for each course was 24.

Date collection. The data collection procedure began on the first day of the activity with the teachers giving out and collecting a pre test for initial knowledge. On finalisation of the course, on the last day, the teachers gave a post-test with identical questions as those of the pre-test and a satisfaction questionnaire (SAT) as well. All questionnaires given in to the teachers were handed over to the main researcher of the course.

After 4 months, the CPA simulation course re-assessment was carried out, using the email address the student indicated in their course inscription application. The email sent by the Continuous Training Unit of the UHCF to participants contained an electronic link to the Google Drive® IT tool for self-completion of two on-line questionnaires: re-evaluation questionnaire of knowledge (RE-TEST) with identical questions to that of the pre and post test and the satisfaction and long-term impact questionnaire (POST-SAT). The participants were given a 15 day period to respond. Two reminders were sent to capture the highest number of students and avoid losses.

Data analysis. For tabulation and statistical analysis of data descriptive statistics were used, with estimation of frequencies, percentages and dispersion measures (standard deviation) (SD), along with the application of inferential statistics to determine the degree of association and compare the questionnaire questions among variables. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests were used to confirm normality, the ranges with the Wilcoxon sign to compare paired samples and the Kruskal–Wallis test to confirm the associations between the different variables. All data were tabulated and calculated with the statistical SPSS v.21® package, the EPIDAT v.4 programme (for sample estimation) and the Excel 2010®spreadsheet.

Ethical considerations. The study upheld all ethical requirements and the necessary administrative permits for execution. Participants were previously informed in writing about the data confidentiality guarantee, the subject under investigation and the aim of the study, together with legal data treatment and its rights.

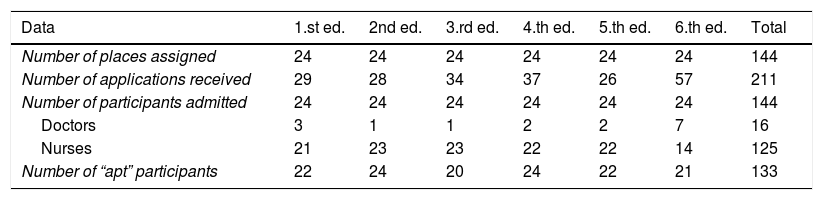

ResultsSix CPA simulation courses were held, all aimed at doctors and nurses in the health area of reference. 24 places were offered for each edition (n=144), and there was a total of 211 applicants. 144 students were finally admitted and 77 were placed on a reserve list. Of those admitted, 3 withdrew during the course (losses) and 133 (91.7%) satisfactorily completed the course with “apt” (Table 1).

Data from the “CPA simulation” courses.

| Data | 1.st ed. | 2nd ed. | 3.rd ed. | 4.th ed. | 5.th ed. | 6.th ed. | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of places assigned | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 144 |

| Number of applications received | 29 | 28 | 34 | 37 | 26 | 57 | 211 |

| Number of participants admitted | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 144 |

| Doctors | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 16 |

| Nurses | 21 | 23 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 14 | 125 |

| Number of “apt” participants | 22 | 24 | 20 | 24 | 22 | 21 | 133 |

ed.: edition.

Sample estimation for inferences was n=92, for 80% statistical power and 95% dependability, on the assumption of 5% possible losses.

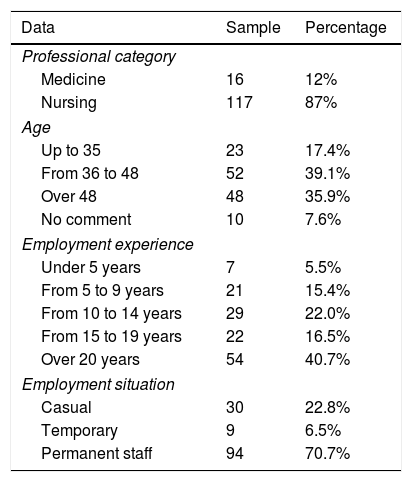

The standard sample profile was a nursing professional aged between 36 and 48, who was permanently employed and had over 20 years of experience. Table 2 describes the socio demographic characteristics of the studied sample (n=133).

Socio-demographic data of the sample.

| Data | Sample | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Professional category | ||

| Medicine | 16 | 12% |

| Nursing | 117 | 87% |

| Age | ||

| Up to 35 | 23 | 17.4% |

| From 36 to 48 | 52 | 39.1% |

| Over 48 | 48 | 35.9% |

| No comment | 10 | 7.6% |

| Employment experience | ||

| Under 5 years | 7 | 5.5% |

| From 5 to 9 years | 21 | 15.4% |

| From 10 to 14 years | 29 | 22.0% |

| From 15 to 19 years | 22 | 16.5% |

| Over 20 years | 54 | 40.7% |

| Employment situation | ||

| Casual | 30 | 22.8% |

| Temporary | 9 | 6.5% |

| Permanent staff | 94 | 70.7% |

The rate of participation was 100% (n=133) for the pre-test, with a knowledge level of 78.5% (SD=1.25). Participation for the post-test was also 100% (n=133) and knowledge level was 94.6% (SD=.78). Finally, in the re-test participation was 69.2% (n=92), with a knowledge level of 88% (SD=.95).

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test value for comparing results obtained in the different tests showed that the variable “number of correct answers” did not have a normal distribution and in the case of the non parametric test of the ranges with the Wilcoxon signal for comparing median and (Fig. 1), there was a significance (p<.001) of the difference between the post-test compared with the re-test (95%CI) (.91–.98). The difference between the re-test and the pre-test (95% CI) (.50–.63) was also significant.

Results of the “satisfaction level” variableThe overall level of satisfaction from respondents (n=133) at the end of the training activity was 91.8% (SD=.39). After4 months, the level of satisfaction of participants who responded (n=92) was established at a mean of 88.4% (95% CI [85.9–91.0]), which showed a high level of satisfaction with the teaching received (Fig. 2).

In general:

- -

50% considered that their knowledge had improved “a lot” with the training received.

- -

96.7% referred to CPA simulation as “very appropriate” for acquiring practical sills faster than with standard learning.

- -

51.6% of professionals stated that after his course “they felt sufficiently prepared” to deal with a CPA.

- -

85.9% of the participants considered that this training activity fully met with their expectations.

- -

91.9% considered that the simulation of emergency situations should be protocolised and should be obligatory.

The following percentages and evaluations were obtained from the transfer and assimilation of knowledge to practical healthcare:

- -

81.5% of professionals stated that “they have varied or would vary” the way they acted to a CPA situation.

- -

82.2% (n=68) of professionals who had not already been in a CPA situation “believe” that the simulation training received “would” change the way they acted.

- -

83.5% (n=18) professionals who had already attended to a patient with CPA, after the simulation training received, stated that they had altered the way in which they proceeded with this situation.

Comparing the level of satisfaction with the socio-demographic data from the questionnaire, we obtained the following statistical data, by using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test:

- •

Professional category: despite the fact that the middle degree of satisfaction was higher in nursing professionals than in medical staff (89% compared with 87%), the difference was not significant (p=.532).

- •

Age range: the level of satisfaction and age variables were connected (p=.027). As age increased, the professionals were “less satisfied” with the CPA simulation course.

- •

Years of experience: it was observed that the differences were significant (p=.026). The professionals with less working experience showed a higher level of satisfaction.

- •

Employment status: there were also significant differences (p=.018) between the three groups (casual, temporary, permanent) with casual and temporary staff being more satisfied with this training than the permanent staff.

Distribution was not normal. In the Kruskal–Wallis test it was observed that the level of satisfaction dropped with age. It was higher in casual and temporary staff, and professionals with less experience.

Finally, 23 comments and/or suggestions were collected, grouped into common themes. They referred to the fact that CPA simulation should be periodically taught in the units, should be obligatory for all staff, and there was also a request that the training be extended to other healthcare collectives. Respondents also commented upon the expediency of developing other training activities involving simulation for other emergency situations.

DiscussionIn this study we started out from the hypothesis that continuous professional training in CPA based on simulation with debriefing has a positive effect on the consolidation of knowledge, meets expectations and has repercussions on satisfaction and transference of acquired knowledge. In the light of the results observed we may maintain that this probably is the case.

The differed assessment method which we used in this study (4 months after training completion) was in keeping with current references, in which it comes to light that on making a final assessment after training, immediate scores may be conditioned by emotional aspects, group situations or either bias, and it is therefore recommendable to verify the training impact over time.3,16 For this reason making an assessment 3–4 months after the end of training and even after longer periods (6 months, one year), provides valid information for optimising the quality of the individual and collective training (repercussion in the organisation) and this in turn highlights any defects and benefits generated by the elements as a whole making up this training process3: teachers, students, organisation, resources, etc., with the establishment of which aspects of the CPA simulation programme have been effective and which could be improved. Examples could be extending the training to other professionals, improving contents, extending schedules, extending training to outside the classroom, developing other simulation contents to emergency situations, etc.

Furthermore, similarly to conventional training activities, in our case, training with simulation also included the evaluation of three essential needs or characteristics16,17:

- -

Diagnosis or initial: the simulation training programme used in the study was designed based on reality and the training needs of the recipients (physicians and nurses), detected by the organisation through surveys on “training needs” and as one of the most solicited courses (221 inscriptions for 144 places).

- -

Training or process: after the first edition of the CPA simulation course, 5 further editions were programmed, due to demand and the innovative teaching method (simulation) and to provide a solution to the “heavy” waiting list of students who had requested a place.

- -

Summative: this is where the study focused on objectives, since we tried to see whether the changes made in the training programme (of the conventional model of teaching CPA to the simulation training) would have the desired interest for this type of learning, which would help us take decisions on future simulation training actions. In the questionnaire 93.5% of participants responded that they “would advise” other colleagues to do the CPA simulation course. The mean score received for the course was 8.4 out of 10.

This study therefore confirms what other publications say when they state that simulation with debriefing in CPA has positive effects in controlling emotions and acquiring better behaviour and cognitive skills.18–24 We consider it to be an excellent learning tool for more practical and objective learning, enabling us to identify and understand what the barriers to implementation and appropriately training professionals for this emergency situation are.25–28

Similarly to our study, the literature also states that training with simulation based on debriefing is fun, natural and produces greater satisfaction,18,22–25 provided that the student is not ridiculed and improvisations are avoided.

However, there are also studies which found that there was no statistical significance with respect to the improvement following training, through learning with debriefing-based simulation.27–29 Our study does reveal a statistical significance in this aspect (p≤.05)in line with the results obtained by Leal et al.30

In line with the studies by Galindo y Visbal31 and Martinez et al.,11 suggestions from professionals provide very important information to guide future training programmes. In the studies of reference, the suggestions and comments received coincide with continuing and fostering simulation in units (outside the classrooms) and the inclusion of interdisciplinary teams.

Moreover, we detected the need to improve the assimilation of knowledge, several months later, with some type of revision or feed-back, since it is confirmed that the loss of knowledge is lineal and progressive over time.

The limitations of this study include the possibility of the existence of an undetected repetition of the questionnaire (bias for repetition). The questionnaire sent was on-line on two separate occasions, as described in the methodology. Despite the fact that the emails stressed the fact that professionals who had already responded did not need to do so again, there is a possibility that a risk of bias in the study existed, if a duplication went undetected. Furthermore, the questionnaires used for data collection were of ad hoc design, which could mean a reliability bias existed, on not using a previously validated tool. There could also have been validity bias in several questions which could have contributed to greater incidence of “non assessable” responses on the Likert scales designed for this research, with the subsequent loss of information and corresponding bias.

With this research study, new lines of investigation have been initiated, with regards to:

- •

Conducting research studies (clinical and quasi-experimental trials), with simulation-debriefing around multidisciplinary training, incorporating the entire interdisciplinary team, to study the transfer of knowledge and practical applicability in professional practice, not on an individual level but with healthcare and non healthcare teams.

- •

Designing and validating systems and models that allow for the formalisation of an assessment procedure for knowledge and the educational impact of simulation, together with its deliverance in the work place.

- •

Applying simulation on different training levels (undergraduate, post graduate and continuous professional development).

- •

Implementing evidence-based healthcare in clinical practice, through simulation.

To conclude, continuous training in CPA, through simulation with debriefing, is consolidated in our environment as an effective tool for acquiring an appropriate and long-lasting level of knowledge. The level of satisfaction achieved was high, since the applied learning method met with participant expectations (it resembled reality) and, above all, because the results improved the skills of the trained professionals (impact), their transfer (implementation) to the work place.

For our part, we would highly recommend that continuous training follows this learning method based on simulation-debriefing, and that the said learning is protocolised in the healthcare area, due to the good results when introducing good practices in approaches to patients in a critical situation as is the case of CPA.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed comply with the ethical regulations of the corresponding committee for human experimentation and the World Medical Association and Declarations of Helsinki.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have adhered to the protocols of their place or work on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The author wishes to thank the Integrated Management Director of Ferrol for their willingness in carrying out this study. Thanks are due to Mr. José A. Pesado and Mr. Ramón Delgado, for their invaluable support and tutoring during the research design phase. Also to all teachers and professionals who collaborated in the surveys, in bibliographic research, in methodology and translation. Finally, thanks are due to Mr. Luis Arantón and Mr. José María Rumbo, for participating as external reviewers and for their advice in redacting this article.

Please cite this article as: Fraga-Sampedro ML. La simulación como herramienta de aprendizaje para la formación continuada ante una parada cardiorrespiratoria. Enferm Intensiva. 2018;29:72–79.