The latest recommendations from the American Heart Association and the European Resuscitation Council invite allowance for the presence of relatives (PR) during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) as an extra measure of family care.

ObjectiveTo discover the opinion of health professionals on the PR during CPR.

MethodCross-sectional observational study through an online survey in Spain, based on a non-probability sample (n=315).

Results45% consider that the PR during CPR is not demanded by users. 64% value the implementation of this practice in a negative or a very negative way. 45% believe that the practice would avoid the feeling of abandonment that is instilled in the relatives, this being the most widely perceived potential benefit. 30% do not believe that it can help reduce the anxiety of relatives. The majority remarked that PR would cause situations of violence, psychological harm in witnesses, and more mistakes during care. 48% feel prepared to perform the role of companion.

ConclusionsMost professionals perceive more risks than benefits, and are not in favour of allowing PR due to a paternalistic attitude, and fear of the reactions that could be presented to the team. Extra-hospital emergency personnel seems to be the group most open to allowing this practice. Most professionals do not feel fully prepared to perform the role of companion.

Las últimas recomendaciones de la American Heart Association y de la European Resuscitation Council invitan a permitir la presencia de familiares (PF) durante la resucitación cardiopulmonar (RCP) como un cuidado familiar más.

ObjetivoConocer la opinión de los profesionales sanitarios sobre la PF durante las maniobras de RCP.

MétodoEstudio observacional descriptivo transversal realizado a través de una encuesta online en España, elaborada con muestreo no probabilístico (n=315).

ResultadosEl 45% cree que la PF durante la RCP no es una demanda de los usuarios. El 64% valora de forma negativa o muy negativa la implantación de esta práctica. El 45% opina que evitaría el sentimiento de abandono que se instala en los allegados, siendo este el beneficio potencial más percibido. El 30% no cree que pueda ayudar a reducir la ansiedad de los familiares. La mayoría señala que la PF provocaría situaciones de violencia, daño psicológico en los testigos y más errores durante la atención. El 48% se siente preparado para desempeñar el papel de acompañante.

ConclusionesLa mayoría de los profesionales percibe más riesgos que beneficios, mostrándose desfavorables a permitir la PF debido a una actitud paternalista y al miedo a las reacciones que estos pudieran presentar hacia el equipo. El personal de Urgencias y Emergencias extrahospitalarias parece el colectivo más abierto a permitir esta práctica. La mayoría de los profesionales no se sienten del todo preparados para desempeñar el papel de acompañante.

The latest publications, including the 2015 updates of the AHA and ERC, recommend allowing family members to be present during CPR manoeuvres due to the possible benefits of this practice.

This is a study of the opinions of doctors and nurses who work in Spain regarding allowing family members to be present during CPR manoeuvres, identifying and analysing the perceived benefits and barriers of this practice as a part of family care.

Implications of the studyThis work will be useful in aiding Emergency Department managers to plan protocol updates based on the latest recommendations of the AHA and ERC, given that the success of the measure depends on the involvement of all professionals. It offers a highly interesting basis for new studies, as well as the key points to understand doubts that healthcare personnel may feel about this proposed change to clinical practice.

Outpatient cardiorespiratory arrest is a potentially reversible catastrophic event that is highly important due to its very low average survival rate. In European countries the latter stands at 10.3% at 30 days, half of the corresponding figure in Spain. Thanks to cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) manoeuvres spontaneous circulation is recovered in 28.6% of cases in Europe, although considerable differences exist between countries. The figure in Spain stands at 33%. The average rate of incidence in the continent is 84 cases per year and 100,000 inhabitants (although this is far lower in Spain, at 28 cases).1

Events of this type mean that healthcare professionals need to display great skill to prevent or reduce associated damage as far as is possible, as well as to minimise the emotional impact they have on family members.

More than 2 decades ago the question started to be raised about whether family members should be allowed to be present during CPR manoeuvres. According to the data available then there was hardly any evidence to the contrary, and it also helped the family to accept a death, if this occurred, while eliminating doubts about whether everything possible had been done. It was also said to make the family feel useful, reducing depression and anxiety. There was abundant evidence in favour of this practice up to 2010, although possible negative effects of resuscitation in the presence of the family in Emergency departments were also in question. It was then said that it would be desirable for staff to feel free to request the family to leave for a while.2,3

The new recommendations of the European Resuscitation Council (ERC)4 and the American Heart Association (AHA)5 were drawn up in 2010. The content relating to ethics refers to a change of attitude among professionals, as they are now more disposed to allow family members to be present or take part in care of the patient. This is due to the supposed beneficial effects of this and the absence of any evidence to the contrary. That same year the AHA concluded that it is better to allow family members to be present (PR) during CPR, for adult patients (level iia, degree C) as well as for paediatric patients (level i, degree B).

The 2015 recommendations of the ERC6 once again emphasise the need to offer family members the possibility of being present, while taking sensitivity and cultural and social variables into account. Regarding paediatric CPR it states that in Western societies family mourning is better accepted when they are present at the death of their children, although this is not the case throughout Europe. Of the 32 European member countries of the ERC, only 10 normally allow family members to be present during CPR. This is allowed in 13 countries for paediatric patients. The cultural factor is decisive when supporting this practice, for children as well as for adults.6

The 2015 AHA update keeps its recommendation to allow the PR during CPR without any changes, except in the case of “excessive stress for personnel” or if this is considered to be harmful “for any reason”.7

The reported benefits for the patient of PR during CPR include increased perception of team members’ professionalism and the humanisation of care.8,9 Nevertheless, the family members of the patient benefit the most from this practice (always on condition that such presence is completely voluntary). There is increasing evidence that being present reduces their anxiety in comparison with waiting in a corridor or room,10–12 and that it also stops them feeling that they have abandoned their loved one as they are separated from them.10,13,14 Likewise, the feeling of being in control that arises from being heard when they want information and being close to the patient in what may be their last moments, and even being asked about ceasing life support manoeuvres also helps to reduce their anxiety levels.10,13,14 There is evidence that this reduces the rate of complicated mourning and depression,15 given that PR facilitates mourning by favouring acceptance, as they better understand descriptions of the state of the patient and know first-hand that everything possible was done.9,16,17 Positive effects on intrafamily relationships have also been reported,8,13,14 together with lower rates of post-traumatic stress and intrusive images12,14,18 even one year after the experience.15

PR during CPR manoeuvres may also have negative consequences,2 although this risk is outweighed by the expected benefits. This practice may increase stress and the possibilities of distraction in healthcare professionals.12,19 It may also interfere with personal coping mechanisms during care, such as humour or distancing.8,11,16 Even so, no harmful effects have been proven for patients or family members.11,14,18 Recent publications adds to the evidence against any supposed psychological hard due to this experience or an increase in lawsuits.9,10,14 Some authors even deny all of the said negative consequences and therefore suggest generalising the recommendation of the AHA to all outpatient cases.18

During emergencies of this type family members generally feel they have to play 3 roles: to accompany the patient at all times (needing to be close or in contact, above all in the case of children), being available to supply information to the care team, and to defend the patient by checking that professionals are doing their job.11 The literature describes the strong desire of family members to have the option of being present during CPR11,16,20 and that they consider it to be a fundamental right.12–14 This support for the practice seems to be firm, above all when the loved ones are children,10,14,17 when they have been present beforehand,10 when the family member in question works in healthcare and when they are asked while experiencing an actual emergency.17

The healthcare professionals who take part in CPR also benefit from this practice. The latest publications describe the possibility of asking family members for information about the patient, as well as increasing their trust in the medical team.11,13,21 The nursing personnel see this in terms of a reduction in the aggressiveness of those accompanying patients and a possible improvement in the image of the profession.10,14

Not much is known about the perceptions of healthcare professionals regarding PR during CPR. Publications to date show that it is understood in terms of family-oriented care. They are generally aware that it may have a positive impact on those who accompany patients at the most critical times, although it may also increase the stress for the medical team.8,12,20 The most common fears are of psychological harm for family members,8,11,12 increasing lawsuits,8,11,13 distractions that lead to errors,8,10,12 poorer quality care due to spending longer with patients,10,19,21 the impact on their own coping strategies8,16,20 and family members’ reactions.13,14,19 These concerns are not only unsupported by the evidence, as there is evidence to the contrary for the majority of them.11,14,18

The professionals in English-speaking countries currently seem to the most favourable to the PR during CPR. On the other hand South and Central America are the areas where they are the least in favour of it.22 Although healthcare systems usually respect the independence of their users, their decision-making capacity may be affected during CPR. When individual preferences are unknown or doubtful it is ethically correct for professionals to deal with emergency situations until such time that they have more information.6 Professional ethics encourages caring for the families of patients, satisfying their needs and preventing psychological harm.8 However, the interpretation of this duty depends on factors such as the sociocultural context,6 professional category,13 sex,17 age20 and years of experience in the profession.21 These factors will determine whether professionals consider their work to take place within the framework of the bioethical principle of independence or the principle of not causing harm in situations of this type.

There is a directly proportional relationship between professional experience of participation in CPR and considering the PR as a users’ right which is supported in practice, and this increases with years of working in the profession.23

As well as these factors, including this practice as a means of caring for family members seems to be strongly influenced by the existence of guides, protocols and institutional support. The creation of the figure of facilitator—or the person in charge of family members—and training received in the hospital are also highly influential.24 Specific training programmes have been shown to be effective in increasing the support of the PR among medical and nursing staff. Institutions are therefore able to modify how professionals perceive this practice.14,23

Based on the above analysis of the situation and the latest recommendations by the ERC and the AHA which confirm the benefits of the PR in CPR, it would be interesting to discover the opinions of healthcare professionals in Spain on the implementation of the PR during CPR as a form of family-oriented care.

ObjectivesThe overall objective is to learn the opinion of healthcare professionals working in Emergency and Critical Care (E&CC) regarding the PR during CPR manoeuvres.

The specific objectives are:

- –

To determine the degree to which E&CC doctors and nurses accept the implementation of a protocol that allows the PR during CPR.

- –

To identify the expected consequences for healthcare personnel deriving from the implementation of a protocol that allows the PR during CPR.

- –

To analyse the degree to which healthcare personnel believe themselves to be prepared to intervene by accompanying family members during CPR.

A cross-sectional descriptive observational study in the form of a self-administered online survey (n=315). The sampling technique was by convenience (non-probabilistic).

AreaTo publicise the online survey within contexts suitable for the recruitment of desirable profiles, a request for collaboration was sent to healthcare workers known to the main researcher and who work in the following hospitals:

- –

University Hospital Gregorio Marañón (Madrid).

- –

University Hospitals Virgen del Rocío and Virgen Macarena (Seville).

- –

Clínica Quirón Sagrado Corazón (Seville).

- –

Primary Care Centres (Comunidad de Madrid): Ibiza, Campo de la Paloma, San Fernando, Alperchines, Reyes Católicos, Prosperidad, Castelló, Mejorada del Campo, Campohermoso, Londres and Miraflores.

- –

Primary Care Centres (Seville): El Greco and Ronda Histórica.

Health Centres are therefore of strategic importance in the recruitment of interviewee profiles, given that transfer selection process make it possible for staff with many years of experience to in other departments to finish their career in Primary Care.

Healthcare workers were also requested to take part in:

- –

Madrid Medical Emergencies Service (SUMMA 112).

- –

The Public Medical Emergency Company in Andalusia (EPES 061).

- –

XX Regional Congress of the Spanish Emergency Medicine Society—Andalusia (SEMES Andalucía).

- –

Official Nursing Associations: Seville and Navarre.

- –

Regional SATSE Trade Unions: Andalusia and Madrid.

- –

Online groups in connection with critically ill patient care: Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn.

Inclusion criteria: medical and/or nursing personnel with work experience in Emergency departments (in hospitals or outside hospitals) or Critical Care.

Exclusion criteria: medical and/or nursing personnel who are not members of a professional association in a Spanish province or city.

VariablesThe sociodemographic and professional variables studied are: sex, age, profession, professional association, years of experience in Emergency/ICU departments, and the department where they have worked the longest.

The dependent variables correspond to:

- –

Opinions on whether family members would like to be able to decide to be present or not during patient CPR.

- –

Opinion on the degree to which their colleagues would accept a protocol that permitted the PR during CPR.

- –

Opinion on the degree to which their colleagues would accept a protocol that permitted the PR during paediatric CPR.

- –

Degree of personal acceptance of the implementation of a protocol that permitted the PR during CPR.

- –

Degree of personal acceptance of the implementation of a protocol that permitted the PR during paediatric CPR.

- –

Consequences expected by healthcare personnel deriving from the implementation of a protocol that permitted the PR during CPR.

- –

Professional self-perception of the hypothetic task of accompanying and informing family members during patient CPR and reasons, in negative cases.

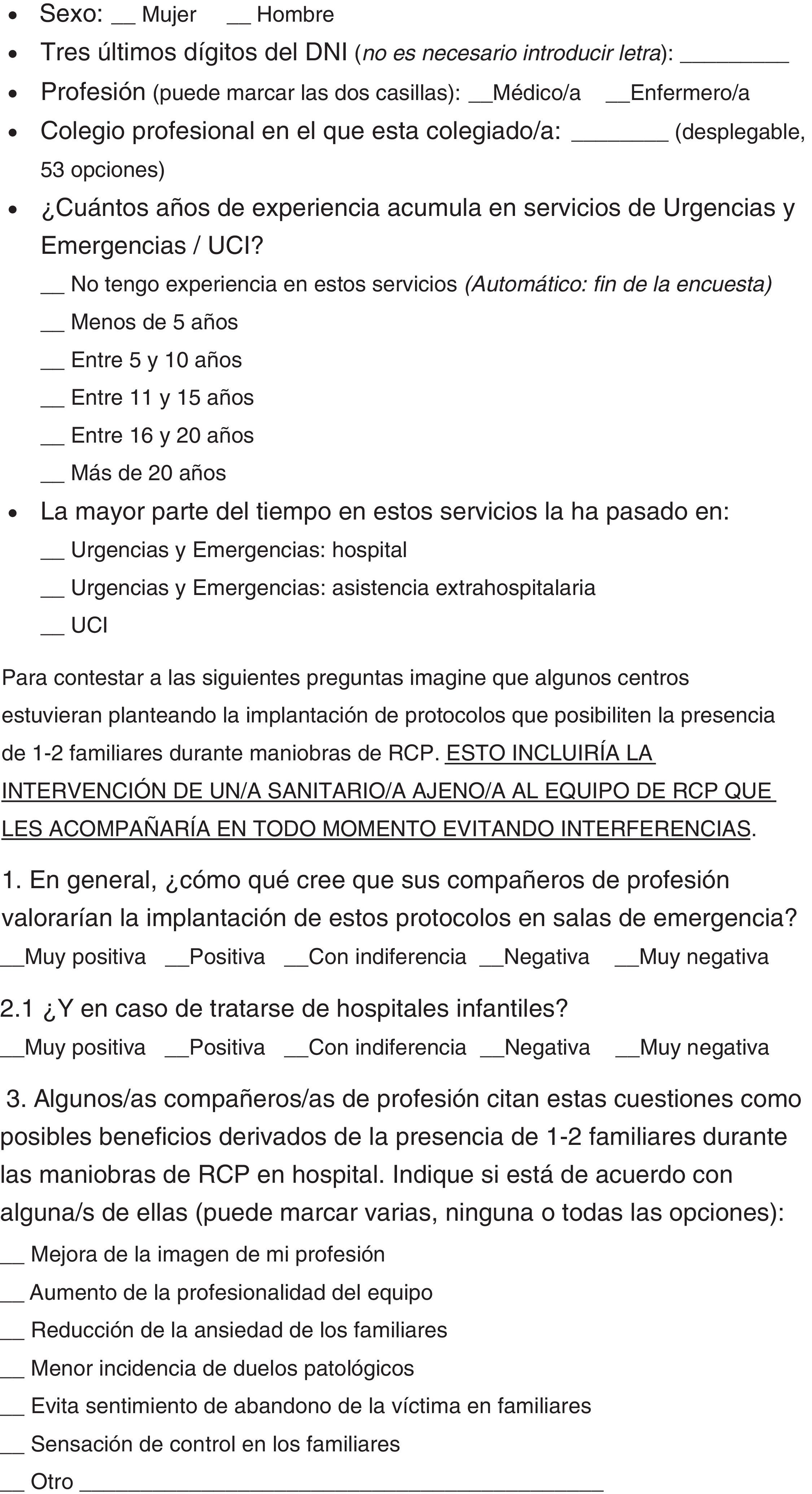

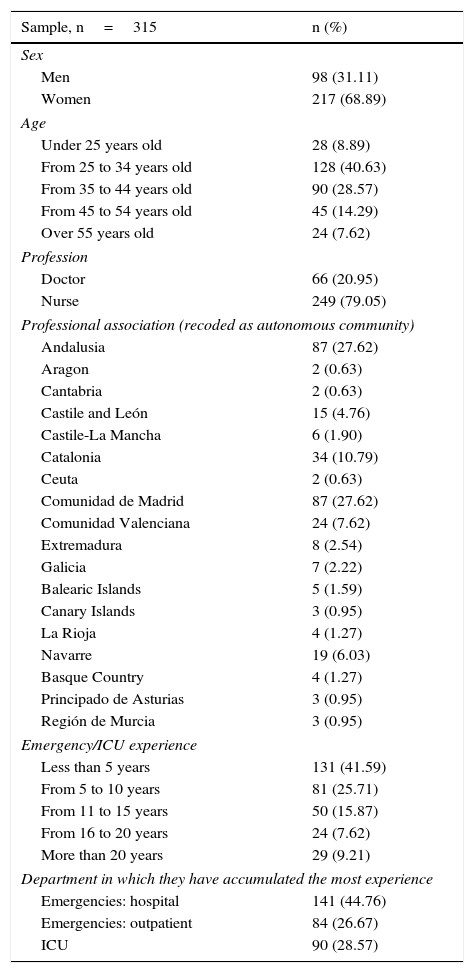

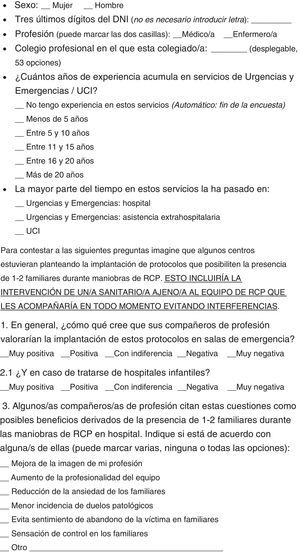

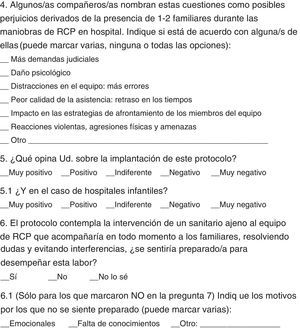

The questionnaire was designed using the online Google Docs word processor. This is shown in Appendix 1. Care was taken with the order of the questions to prevent spontaneous positions being taken regarding the PR during CPR. That is why questions about this are asked after examining the expected consequences of the practice, thereby favouring previous though about the question.

Given the possibility that a single individual could take part in the study twice, a control question was asked (the 3 last numbers of their identity card number).

Following trial of the document among healthcare workers in the area of the main researcher, the questionnaire was opened on 11 August 2015. Strategic individuals were then contacted to publicise the questionnaire. On 15 November 2015 the survey was closed and the records that fulfilled the exclusion criteria were screened out.

Data analysisV. 23.0 of the SPSS program was used for univariant descriptive analysis by percentages and frequencies, as well as bivariant analysis using the non-parametric chi-squared test, including statistics to synthesise relationships. Statistical tests were considered to be significant when the critical level observed was less than 5% (P<.05).

Ethical considerationsAlthough this study did not involve any intervention whatsoever in patients or professionals, the information gathered on interviewees’ perceptions and training is sensitive. Therefore, and in compliance with Organic Law 15/1999 on Personal Data Protection, each record is identified by an assigned number to guarantee the anonymity of the subject who answered the survey. This study was approved by the authorised Research Ethics Committee.

Prior to accessing the questionnaire, the participants were informed that this is a research project and the inclusion criteria were described. They were also informed that it is anonymous and given its estimated duration. The email address of the author was also supplied, for contact in case of doubts, comments or a request to access the results. The computer tool used was programmed to thank participants for their help, as they took part without any economic incentives, given that this work had no financing whatsoever.

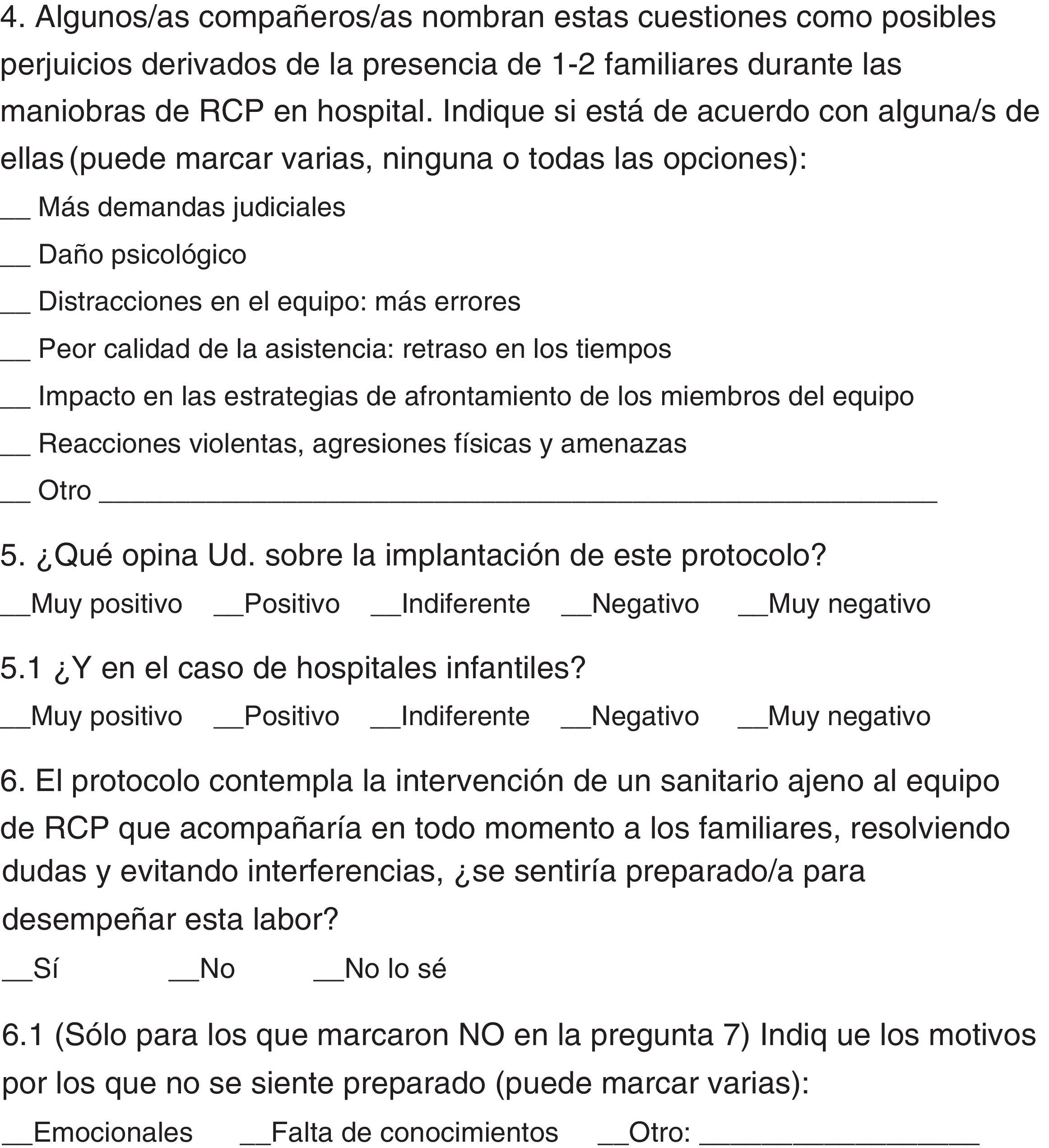

Results348 participations were registered, of which 315 (90.52%) fulfilled the requisites for admission in the study. The demographic and professional characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Demographic and professional characteristics of the participants.

| Sample, n=315 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Men | 98 (31.11) |

| Women | 217 (68.89) |

| Age | |

| Under 25 years old | 28 (8.89) |

| From 25 to 34 years old | 128 (40.63) |

| From 35 to 44 years old | 90 (28.57) |

| From 45 to 54 years old | 45 (14.29) |

| Over 55 years old | 24 (7.62) |

| Profession | |

| Doctor | 66 (20.95) |

| Nurse | 249 (79.05) |

| Professional association (recoded as autonomous community) | |

| Andalusia | 87 (27.62) |

| Aragon | 2 (0.63) |

| Cantabria | 2 (0.63) |

| Castile and León | 15 (4.76) |

| Castile-La Mancha | 6 (1.90) |

| Catalonia | 34 (10.79) |

| Ceuta | 2 (0.63) |

| Comunidad de Madrid | 87 (27.62) |

| Comunidad Valenciana | 24 (7.62) |

| Extremadura | 8 (2.54) |

| Galicia | 7 (2.22) |

| Balearic Islands | 5 (1.59) |

| Canary Islands | 3 (0.95) |

| La Rioja | 4 (1.27) |

| Navarre | 19 (6.03) |

| Basque Country | 4 (1.27) |

| Principado de Asturias | 3 (0.95) |

| Región de Murcia | 3 (0.95) |

| Emergency/ICU experience | |

| Less than 5 years | 131 (41.59) |

| From 5 to 10 years | 81 (25.71) |

| From 11 to 15 years | 50 (15.87) |

| From 16 to 20 years | 24 (7.62) |

| More than 20 years | 29 (9.21) |

| Department in which they have accumulated the most experience | |

| Emergencies: hospital | 141 (44.76) |

| Emergencies: outpatient | 84 (26.67) |

| ICU | 90 (28.57) |

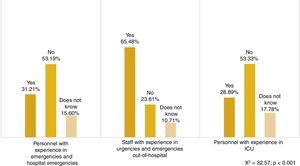

The study does not show a uniform response among professionals about whether the PR is a user demand. 45.40% of the professional surveyed (n=143) believe that they do not want the option of deciding whether to be present or not during the resuscitation of a family member or someone they are close to. However, 39.68% (n=125) believe that they do, while the others (14.92%, n=47) are unclear on this point.

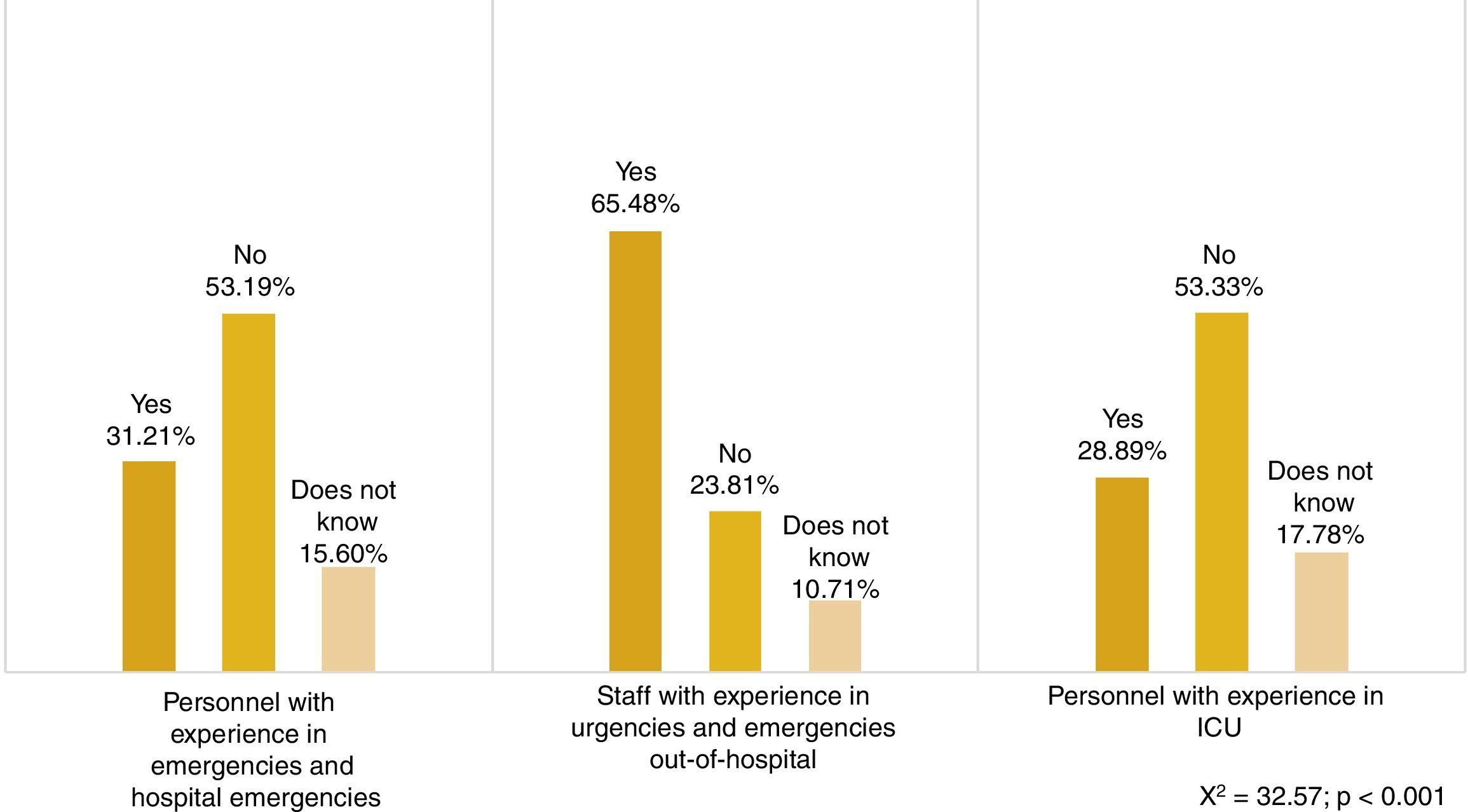

On the contrary, a significant finding is that almost 3 thirds of Emergency and outpatient emergency personnel (65.48%, n=55) believe that there is a demand among family members to be present (Fig. 1).

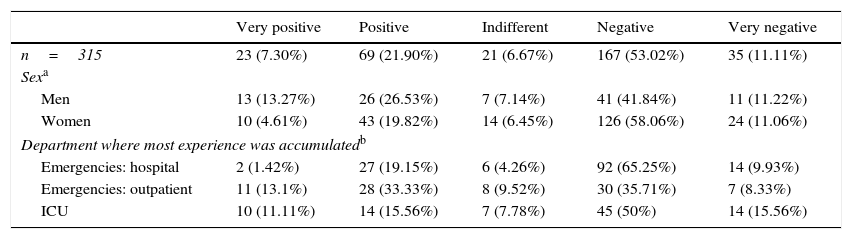

More than half of the participants (64.13%, n=202) consider the implementation of this practice in hospital emergency facilities to be negative or very negative (Table 2). Less than one third of the sample considered this option to be positive or very positive (29.20%, n=92), although the group with the greatest experience in the Emergency or outpatient emergency departments rejected this to a lesser degree (44.04%, n=37) (χ2=33.15; P<.001). Support for this protocol was significantly lower among the women (24.43%, n=53 vs 39.80%, n=39) (χ2=11.72; P=.020).

The opinions of the participants on permitting the practice.

| Very positive | Positive | Indifferent | Negative | Very negative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=315 | 23 (7.30%) | 69 (21.90%) | 21 (6.67%) | 167 (53.02%) | 35 (11.11%) |

| Sexa | |||||

| Men | 13 (13.27%) | 26 (26.53%) | 7 (7.14%) | 41 (41.84%) | 11 (11.22%) |

| Women | 10 (4.61%) | 43 (19.82%) | 14 (6.45%) | 126 (58.06%) | 24 (11.06%) |

| Department where most experience was accumulatedb | |||||

| Emergencies: hospital | 2 (1.42%) | 27 (19.15%) | 6 (4.26%) | 92 (65.25%) | 14 (9.93%) |

| Emergencies: outpatient | 11 (13.1%) | 28 (33.33%) | 8 (9.52%) | 30 (35.71%) | 7 (8.33%) |

| ICU | 10 (11.11%) | 14 (15.56%) | 7 (7.78%) | 45 (50%) | 14 (15.56%) |

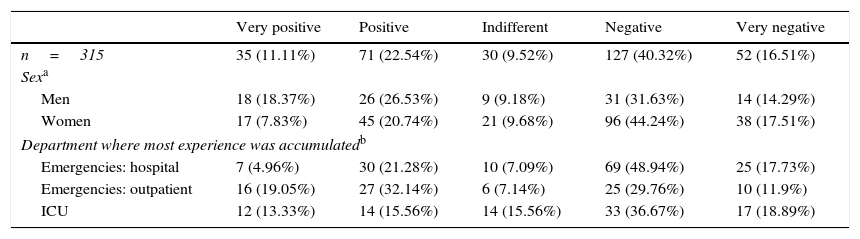

When they were asked about the implementation of this practice in paediatric emergency wards (Table 3) rejection of the PR during CPR fell by 7.30% and support for this protocol rose by 4.45%. Support remained significantly lower among the women (28.57%, n=62) (χ2=10.85; P=.028), although there was less rejection of this measure than was the case for adult patients (61.75%, n=134 vs 69.12%; n=150). The only group in favour of permitting the PR during CPR in paediatric patients were workers in the Emergency and outpatient emergency departments (51.19%, n=43) (χ2=26.99; P=.001).

The opinions of the participants on permitting the practice in paediatric emergency wards.

| Very positive | Positive | Indifferent | Negative | Very negative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=315 | 35 (11.11%) | 71 (22.54%) | 30 (9.52%) | 127 (40.32%) | 52 (16.51%) |

| Sexa | |||||

| Men | 18 (18.37%) | 26 (26.53%) | 9 (9.18%) | 31 (31.63%) | 14 (14.29%) |

| Women | 17 (7.83%) | 45 (20.74%) | 21 (9.68%) | 96 (44.24%) | 38 (17.51%) |

| Department where most experience was accumulatedb | |||||

| Emergencies: hospital | 7 (4.96%) | 30 (21.28%) | 10 (7.09%) | 69 (48.94%) | 25 (17.73%) |

| Emergencies: outpatient | 16 (19.05%) | 27 (32.14%) | 6 (7.14%) | 25 (29.76%) | 10 (11.9%) |

| ICU | 12 (13.33%) | 14 (15.56%) | 14 (15.56%) | 33 (36.67%) | 17 (18.89%) |

These participants are generally more in favour of the PR during CPR than their colleagues (29.20%, n=106 vs 10.48%, n=92), as the latter are generally thought to have a more negative opinion than that of the sample (85.71%, n=270 vs 64.13%, n=202).

If the change in protocol affected only paediatric Emergency wards the participants still believe that they are more in favour of this than their colleagues (33.65%, n=106 vs 20.00%, n=63), as they find the entrance of family members less negative (56.83%, n=179 vs 72.92%, n=236).

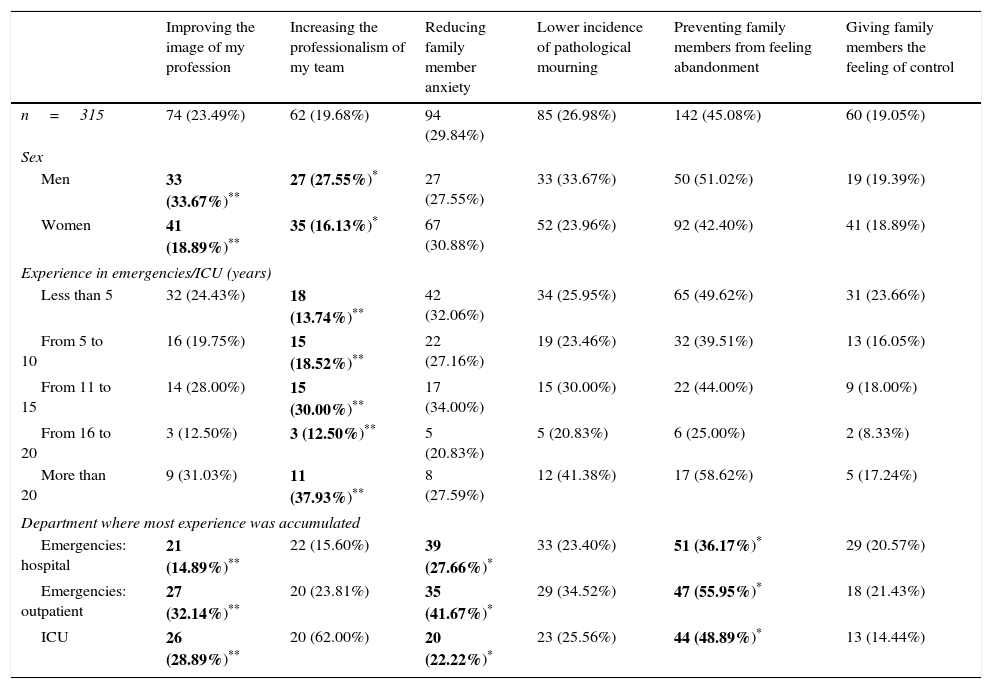

Expected consequences for healthcare staff deriving from the implementation of a protocol that permits the presence of family members during cardiopulmonary resuscitationA list of the benefits and negative effects cited by healthcare professionals in the literature as the expected results of the implementation of this protocol was suggested.

45.08% of the sample (n=142) believe that allowing the PR would prevent the feeling of abandonment felt by those close to a patient being treated in another room. This is the most widely expected benefit, although not even half of the sample marked this box in the survey. Not even one third of the professionals (29.84%, n=94) support the idea that this protocol could help to reduce the anxiety felt by family members, even though it was the second most-expected benefit. The majority of the outpatient healthcare workers stated that the PR could help to reduce the feeling of abandonment felt by those close to patients (55.95%, n=47) (χ2=9.06; P=.011), and they consider the possible improvement in the image of the profession to be more positive than do the others (32.14%, n=27) (χ2=10.76; P=.005), as well as reducing the anxiety felt by family members (41.67%, n=35) (χ2=8.43; P=.015).

There were also significant results in terms of sex. 37.67% of the male participants (n=33) state that the PR may improve the image of their profession, vs 18.89% of the women (n=41) (χ2=8.20; P=.004). They identified the improvement in the professionalism of the medical team more clearly as a possible result of PR (27.33%, n=35 vs 16.13%, n=27) (χ2=5.57; P=.018). The participants with more than 20 years’ experience in caring for critically ill patients were more likely to perceive this benefit (37.93%, n=11) than the other profiles (χ2=13.25; P=.010).

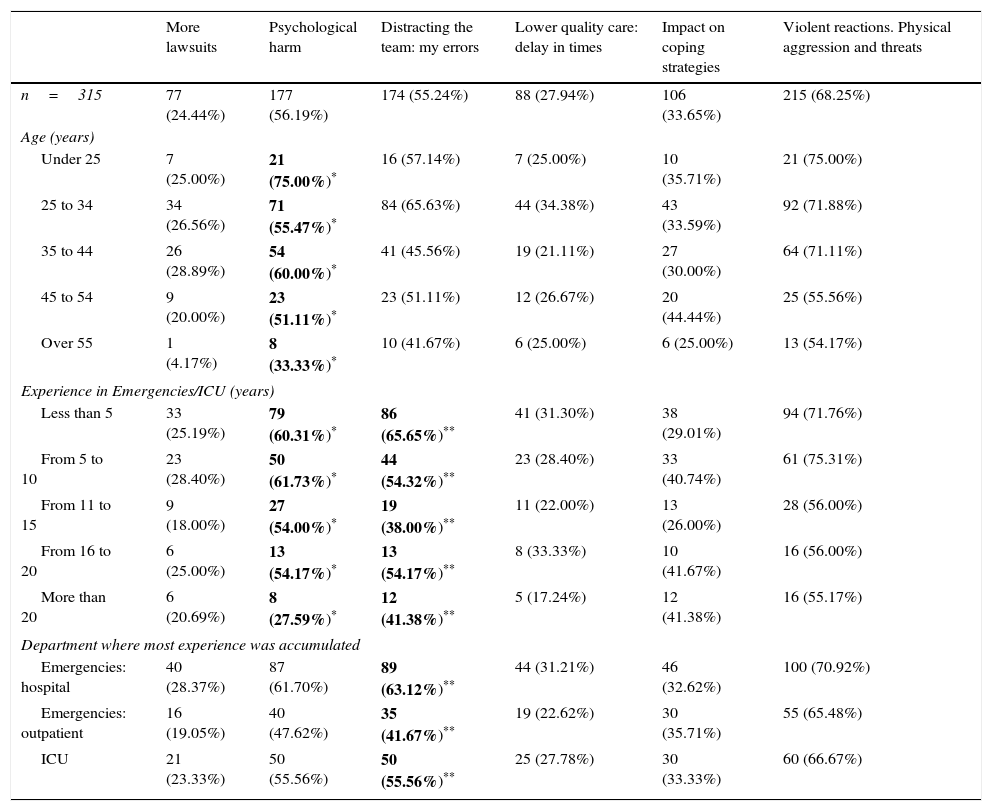

Regarding the expected negative effects of this protocol, the majority of the participants state that it would give rise to violent situations and physical aggression as well as threats (68.25%, n=215), with psychological harm for those present (56.19%, n=177) and more errors during treatment due to distraction of the medical team (55.24%, n=174).

The older professionals and those with more experience seem less likely to believe that the PR may give rise to psychological harm. The participants aged over 55 years old were the only group where a majority did not support this idea (33.33%, n=8) (χ2=10.15; P=.038). This was also the case for the workers with more than 20 years’ experience (27.59%, n=8) (χ2=11.69; P=.020). There is a positive association between years of experience and the perception that this practice is psychologically harmful.

Significantly more of the professionals with less than 5 years’ experience of working with critically ill patients believe that the PR during CPR may lead to errors due to distraction (65.65%, n=86) (χ2=14.04; P=.007). On the contrary, the group of workers in the Emergency and outpatient Emergency departments are significantly less likely than the other respondents to perceive this risk (41.67%, n=37) (χ2=0.176; P=.007).

The open questions detected other possible benefits and negative effects that were not included in the survey. These answers were grouped around 3 potential benefits: improvement in the communication between healthcare workers and families (n=2), the possibility that those close to patients would not feel any doubts about whether everything possible had been done (n=2), and their participation in the process (n=1). 3 possible negative effects were also mentioned: increased anxiety of family members (n=4), of healthcare workers (n=2) and the obligation to physically adapt Emergency facilities to permit the PR (n=1).

The significant results in connection with the positive and negative effects which respondents expect are shown in Tables 4 and 5, respectively.

Benefits the participants expect deriving from the practice.

| Improving the image of my profession | Increasing the professionalism of my team | Reducing family member anxiety | Lower incidence of pathological mourning | Preventing family members from feeling abandonment | Giving family members the feeling of control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=315 | 74 (23.49%) | 62 (19.68%) | 94 (29.84%) | 85 (26.98%) | 142 (45.08%) | 60 (19.05%) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 33 (33.67%)** | 27 (27.55%)* | 27 (27.55%) | 33 (33.67%) | 50 (51.02%) | 19 (19.39%) |

| Women | 41 (18.89%)** | 35 (16.13%)* | 67 (30.88%) | 52 (23.96%) | 92 (42.40%) | 41 (18.89%) |

| Experience in emergencies/ICU (years) | ||||||

| Less than 5 | 32 (24.43%) | 18 (13.74%)** | 42 (32.06%) | 34 (25.95%) | 65 (49.62%) | 31 (23.66%) |

| From 5 to 10 | 16 (19.75%) | 15 (18.52%)** | 22 (27.16%) | 19 (23.46%) | 32 (39.51%) | 13 (16.05%) |

| From 11 to 15 | 14 (28.00%) | 15 (30.00%)** | 17 (34.00%) | 15 (30.00%) | 22 (44.00%) | 9 (18.00%) |

| From 16 to 20 | 3 (12.50%) | 3 (12.50%)** | 5 (20.83%) | 5 (20.83%) | 6 (25.00%) | 2 (8.33%) |

| More than 20 | 9 (31.03%) | 11 (37.93%)** | 8 (27.59%) | 12 (41.38%) | 17 (58.62%) | 5 (17.24%) |

| Department where most experience was accumulated | ||||||

| Emergencies: hospital | 21 (14.89%)** | 22 (15.60%) | 39 (27.66%)* | 33 (23.40%) | 51 (36.17%)* | 29 (20.57%) |

| Emergencies: outpatient | 27 (32.14%)** | 20 (23.81%) | 35 (41.67%)* | 29 (34.52%) | 47 (55.95%)* | 18 (21.43%) |

| ICU | 26 (28.89%)** | 20 (62.00%) | 20 (22.22%)* | 23 (25.56%) | 44 (48.89%)* | 13 (14.44%) |

Negative effects expected by the participants deriving from the practice.

| More lawsuits | Psychological harm | Distracting the team: my errors | Lower quality care: delay in times | Impact on coping strategies | Violent reactions. Physical aggression and threats | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=315 | 77 (24.44%) | 177 (56.19%) | 174 (55.24%) | 88 (27.94%) | 106 (33.65%) | 215 (68.25%) |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Under 25 | 7 (25.00%) | 21 (75.00%)* | 16 (57.14%) | 7 (25.00%) | 10 (35.71%) | 21 (75.00%) |

| 25 to 34 | 34 (26.56%) | 71 (55.47%)* | 84 (65.63%) | 44 (34.38%) | 43 (33.59%) | 92 (71.88%) |

| 35 to 44 | 26 (28.89%) | 54 (60.00%)* | 41 (45.56%) | 19 (21.11%) | 27 (30.00%) | 64 (71.11%) |

| 45 to 54 | 9 (20.00%) | 23 (51.11%)* | 23 (51.11%) | 12 (26.67%) | 20 (44.44%) | 25 (55.56%) |

| Over 55 | 1 (4.17%) | 8 (33.33%)* | 10 (41.67%) | 6 (25.00%) | 6 (25.00%) | 13 (54.17%) |

| Experience in Emergencies/ICU (years) | ||||||

| Less than 5 | 33 (25.19%) | 79 (60.31%)* | 86 (65.65%)** | 41 (31.30%) | 38 (29.01%) | 94 (71.76%) |

| From 5 to 10 | 23 (28.40%) | 50 (61.73%)* | 44 (54.32%)** | 23 (28.40%) | 33 (40.74%) | 61 (75.31%) |

| From 11 to 15 | 9 (18.00%) | 27 (54.00%)* | 19 (38.00%)** | 11 (22.00%) | 13 (26.00%) | 28 (56.00%) |

| From 16 to 20 | 6 (25.00%) | 13 (54.17%)* | 13 (54.17%)** | 8 (33.33%) | 10 (41.67%) | 16 (56.00%) |

| More than 20 | 6 (20.69%) | 8 (27.59%)* | 12 (41.38%)** | 5 (17.24%) | 12 (41.38%) | 16 (55.17%) |

| Department where most experience was accumulated | ||||||

| Emergencies: hospital | 40 (28.37%) | 87 (61.70%) | 89 (63.12%)** | 44 (31.21%) | 46 (32.62%) | 100 (70.92%) |

| Emergencies: outpatient | 16 (19.05%) | 40 (47.62%) | 35 (41.67%)** | 19 (22.62%) | 30 (35.71%) | 55 (65.48%) |

| ICU | 21 (23.33%) | 50 (55.56%) | 50 (55.56%)** | 25 (27.78%) | 30 (33.33%) | 60 (66.67%) |

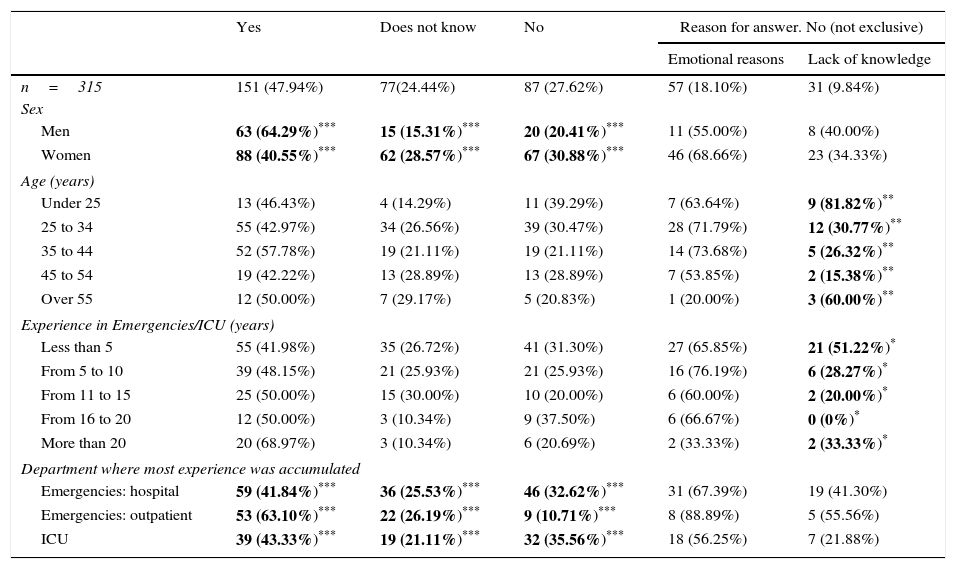

47.94% of the respondents (n=151) state that they feel prepared to accompany family members and resolve their doubts, preventing possible interference with the work of the medical team (Table 6).

Degree to which they consider themselves prepared for the task of accompanying.

| Yes | Does not know | No | Reason for answer. No (not exclusive) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional reasons | Lack of knowledge | ||||

| n=315 | 151 (47.94%) | 77(24.44%) | 87 (27.62%) | 57 (18.10%) | 31 (9.84%) |

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 63 (64.29%)*** | 15 (15.31%)*** | 20 (20.41%)*** | 11 (55.00%) | 8 (40.00%) |

| Women | 88 (40.55%)*** | 62 (28.57%)*** | 67 (30.88%)*** | 46 (68.66%) | 23 (34.33%) |

| Age (years) | |||||

| Under 25 | 13 (46.43%) | 4 (14.29%) | 11 (39.29%) | 7 (63.64%) | 9 (81.82%)** |

| 25 to 34 | 55 (42.97%) | 34 (26.56%) | 39 (30.47%) | 28 (71.79%) | 12 (30.77%)** |

| 35 to 44 | 52 (57.78%) | 19 (21.11%) | 19 (21.11%) | 14 (73.68%) | 5 (26.32%)** |

| 45 to 54 | 19 (42.22%) | 13 (28.89%) | 13 (28.89%) | 7 (53.85%) | 2 (15.38%)** |

| Over 55 | 12 (50.00%) | 7 (29.17%) | 5 (20.83%) | 1 (20.00%) | 3 (60.00%)** |

| Experience in Emergencies/ICU (years) | |||||

| Less than 5 | 55 (41.98%) | 35 (26.72%) | 41 (31.30%) | 27 (65.85%) | 21 (51.22%)* |

| From 5 to 10 | 39 (48.15%) | 21 (25.93%) | 21 (25.93%) | 16 (76.19%) | 6 (28.27%)* |

| From 11 to 15 | 25 (50.00%) | 15 (30.00%) | 10 (20.00%) | 6 (60.00%) | 2 (20.00%)* |

| From 16 to 20 | 12 (50.00%) | 3 (10.34%) | 9 (37.50%) | 6 (66.67%) | 0 (0%)* |

| More than 20 | 20 (68.97%) | 3 (10.34%) | 6 (20.69%) | 2 (33.33%) | 2 (33.33%)* |

| Department where most experience was accumulated | |||||

| Emergencies: hospital | 59 (41.84%)*** | 36 (25.53%)*** | 46 (32.62%)*** | 31 (67.39%) | 19 (41.30%) |

| Emergencies: outpatient | 53 (63.10%)*** | 22 (26.19%)*** | 9 (10.71%)*** | 8 (88.89%) | 5 (55.56%) |

| ICU | 39 (43.33%)*** | 19 (21.11%)*** | 32 (35.56%)*** | 18 (56.25%) | 7 (21.88%) |

27.62% (n=87) state that they do not feel prepared for such tasks. This would seem to have more to do with emotional motives than it does any lack of knowledge (65.52%, n=57 vs 35.63%, n=31). 24.44% (n=77) doubt their academic preparation for performing the tasks involved.

Men consider themselves to be more prepared for these tasks (64.29%, n=63) (χ2=15.47; P=.000), closely followed by the group of workers in the Emergency and outpatient Emergency departments (63.10%, n=53) (χ2=18.12; P=.001). The youngest group (those under the age of 25 years old) feel less prepared than the other participants due to lack of knowledge (81.82%, n=9) (χ2=14.97; P=.005), as do those with less than 5 years’ experience working in the departments studied (51.22%, n=21) (χ2=10.86; P=.028).

Replies to the open question on the reasons why personnel stated that they did not feel prepared included the following: it is a task for psychologists or personnel trained in managing crisis situations (n=3); discrepancy of clinical criteria with colleagues (n=2) and moral reasons (n=1).

DiscussionDegree of acceptation of the implementation of a protocol that permits the presence of family members during cardiopulmonary resuscitationThe study, which cannot be extrapolated due to methodological questions, reflects the unfavourable opinion of E&CC healthcare professionals regarding the implementation of a protocol that permits the PR during CPR manoeuvres (64.13% are against this).

No significant differences were found between the answers of medical and nursing personnel, as is suggested by McAlvin and Carew-Lyons,10 Achury-Saldaña et al.12 as well as Fell.13

Although the PR is considered to be a right by the users themselves,12–14 6 of every 4 participants did not clearly identify this demand in their everyday work. Kosowan and Jensen25 investigated this matter at a local level in Edmonton (Canada) and found similar results.

If they are representative, the results of this work would indicate that Spanish professionals are more open to permitting the PR than is the case in Germany, according to the survey published by Köberich et al.19 This used a similar methodology for male and female Intensive Care nurses (29.2% vs 17.5%). Unlike their Spanish counterparts, they did not seem to consider themselves to be much more favourable to the PR than their colleagues. It would be interesting to study if this erroneous perception of the opinions of their colleagues would be a barrier against the implementation of this practice in Spain.

The approval rating in this study of the PR during CPR is within the range where Colbert and Adler22 locate the European average (at 25–30%). Nevertheless, this datum has to be accepted with care as almost 80% of the participants in this study work in France.

As Dall’Orso and Concha20 rightly intuited, there is a significant difference between perceptions within hospitals and in outpatient departments. The workers in Emergency departments and outpatient Emergencies are the only ones in favour of the PR, which they clearly recognise to be a user demand. This is one of the main findings of this study, as CPR often takes place in homes, where there is usually PR. This fact should lead us to reflect, given that they probably do not imagine the CPR context considered in the survey, but rather where they remember it occurring.

Based on their own review Dall’Orso and Concha20 correctly state that there may be difference in the degree to which the PR is accepted between adult and paediatric care. Parents clearly want to be present during the CPR of their children.10 Although this research does not differentiate between general and paediatric Emergency wards, this practice is rejected less in the case of children. 51.19% of outpatient Emergency workers support the PR in these cases.

This study does not investigate why the age of the patient modifies the degree to which the PR is accepted. It may be explained by the hypothesis that the participants answered this question as if they were emotionally-motivated users rather than professionals. It would have been highly interesting to add a variable that would indicate whether the participants were parents or lived with children.

An outstanding finding is that women display significantly less support than men for the practice in question, in general as well as for paediatric patients in particular. However, Dwyer17 states that the majority of the population residing in Central Queensland (Australia) support it, without any significant differences according to sex. This was not the case for paediatric patients, where women are more in favour. Nor did Dall’Orso and Concha20 find any significant crossed differences between these variables in the study they undertook in the Bío-Bío region of Chile. It would be interesting to analyse this question according to sex, given that in Dwyer's study men and women were said to have different reasons for not wanting to be present during CPR: while women fear feeling too much pain, the men worry about hindering the work of the team. It seems evident that, if the results can be extrapolated, this work underlines a difference between Spain and Australia in terms of sex.

Expected consequences for healthcare personnelTo understand the rejection by a majority of healthcare staff of the PR during CPR, it is necessary to know why they expect the consequences of the experience to be more negative than positive.

The potential benefit identified by workers the most often is that of preventing the feeling of abandonment in family members (45.08%), although this is not enough for them to believe their presence would be justified. The professionals working in the Emergency and outpatient Emergency departments are more likely to identify this as a possible benefit. This difference in opinions may be due, as was pointed out above, to the fact that this group is being asked about something they habitually do rather than a hypothetical situation they have to imagine.

It should be pointed out that the majority of respondents, contrary to the findings of the study by Achury-Saldaña et al.,12 do not perceive one of the potential benefits of the PR best supported by the evidence: a reduction in the anxiety of those present,10–12 even over the long term.15 Although more Emergency and outpatient Emergency department participants identify this than is the case in other groups, not even half of them believe that the PR may help family members in this way. If this is representative, it would be interesting to prepare a qualitative research project to understand the motivations leading to this result.

Some results of this study are illuminating, unexpected and hard to interpret. Men are more likely than women to believe that the PR during CPR may improve the image of their profession, independently of whether they are medical or nursing personnel. More clearly than the other profiles, they also identify the capacity of this practice to improve the professionalism of the team. I.e., while they state that their work in care is better than the social image of the same (“we work better than people think”), they also admit that there is room for improvement in team professionalism (“we’d work better if people were watching”). Although a priori this seems to be a contradiction, we lack sufficient data for the creation of a hypothesis that would explain it. One point that should guide us is the fact that Emergency and outpatient Emergency department professionals are more likely than other groups to support this statement (32.14%), and that those with more than 20 years’ experience stand out by identifying it as the second potential benefit mentioned (37.93%).

The negative effects expected the most widely by the participants were violent reactions by those close to patients (68.25%), psychological harm that may be caused by the experience (56.19%) and the increase in errors due to distraction (55.24%). From the frequencies of the answers obtained it may be deduced that this practice is considered to be harmful above all for the medical team itself, followed by family members and finally for the patient, who would be the last to suffer the impact of the consequences.

Evaluation of the benefit-risk balance corresponding to this practice currently seems to be clearly in favour of the same in the latest scientific publications and international recommendations. Evidence exists that goes against the harmful effects most widely expected by participants,9,12,14 so that the results of this study underline rejection due to prejudice. Mottillo and Delaney18 mention 4 aggressive or conflictive reactions to healthcare personnel in the 507 cases included in their study (less than 1% of the sample), which was undertaken in Montreal. Such prejudice may explain why this practice is not included a priori in the bioethical principle of Independence or beneficence, but rather in the absence of harm: they try to prevent harm to the patient and those close to the patient. This is therefore a paternalistic attitude. The most experienced group is here the one that seems to lack this prejudice.

To continue the tendency towards including the PR as a part of family-oriented care specific educational intervention seems to be required, as this has been shown to be effective in eliminating prejudice and therefore modifies the attitudes of professionals.14,23 It is important to underline that the majority of staff will not support such care if they continue to see family members or people close to patients as a potential threat. Nevertheless, workers do eventually come to consider this practice as a part of defending independence or benefiting themselves.

As could be expected, the least expert personnel associate the PR with a higher probability of committing errors due to distraction. Kosowan and Jensen25 state that fewer than half of the professionals they surveyed after CPR with the PR felt that their work had been affected. This association between the PR and distractions may be due among less experienced workers to the fact that they still consider themselves to be learning, so that the PR may multiply the consequences of any error they make.

Degree to which healthcare personnel consider themselves to be ready to act by accompanying family members during cardiopulmonary resuscitationIt should be pointed out that solely outpatient Emergency workers feel prepared to offer this care. Although they are more used to dealing with patient family members than those who work in hospitals (63.10% vs 42.42%), the degree to which they consider themselves to be prepared reveals a certain degree of insecurity in outpatient healthcare workers regarding family care at critical junctures. Although the majority of the respondents (the women above all) mention emotional reasons, a notable percentage of professionals admit to a lack of knowledge, as Dall’Orso and Concha20 found. As could be expected, this is so above all for those under the age of 25 years old and those with less than 5 years’ experience in treating critically ill patients.

This confirms one of the conclusions of the study that preceded this research.24 This identified the training of professionals as one of the key points in acceptation of this practice by healthcare personnel. As Feagan and Fisher23 point out, specific training not only affects self-evaluation of their skills to carry out the work of accompanying family members, as it also affects the perception of FP as one more part of family care. Ferreira et al.21 go further and propose complementing this training with a programme to raise the awareness of professionals to promote the practice in paediatric emergency wards.

Study limitationThe chief methodological limitation of this study is the difficulty of calculating a representative sample. This is because the Ministry of Health is currently unaware of how many healthcare professionals are working in Spain.26 Due to temporary restrictions no provincial data were requested from the 104 professional associations (52 Medical ones and 52 for Nursing).

The results cannot be generalised because sampling was undertaken “by convenience”. This non-probabilistic sampling means that the sample size is not defined by statistical parameters but rather by economic and temporal limitations.

The study does not take into account the context in which professionals acquired their professional experience or how many cardiorespiratory arrests they have treated.

Additionally, the speciality of Emergencies does not exist in all of the autonomous communities. This is why such departments usually contain professionals in Family and Community Medicine or Intensive Care. Nurses usually require specific training to work with critically ill patients, although this is not a legal obligation. This means that not all teams are composed of professionals who have received the same training.

Another limitation to be taken into account is the functional difference between the different emergency teams, given that this depends on the regulations in each autonomous community and the medical equipment in the area.

ConclusionsAfter undertaking this research and based on the objectives that were set for the same, the conclusions that may be drawn are:

- –

The level of acceptance among healthcare professionals who treat critically ill patients of the implementation of a protocol that permits the PR during CPR in Emergency wards is at a low level, and it is not clearly identified as a user demand.

- –

The consequences that healthcare personnel expect to arise from the implementation of this protocol seem to centre on the possibility of violent reactions by family members, avoidable emotional harm and errors by the medical team caused by distractions.

- –

The degree to which they consider themselves to be prepared to undertake the tasks of accompanying and informing family members during CPR is insufficient, as somewhat more than half of them do not feel fully prepared to undertake these, due to emotional reasons above all.

The conclusion is therefore that the unfavourable opinion of E&CC healthcare professionals on permitting the PR during CPR shows a considerable gap between the published evidence on expected consequences and those expressed by the participants. Their attitude is therefore paternalistic and strongly marked by fear of the reactions of those close to patients to the members of medical teams. It would therefore be of interest for future studies to use a qualitative approach to discover the reasons why professionals give answers that are so far removed from a clear evidence-based tendency in favour of allowing the PR during CPR.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank Dr. Ángel Lizcano Álvarez, PhD, the Academic Regulatory Vice deacon of Rey Juan Carlos University, Madrid, for his help.

Dear Colleague,

This short questionnaire is part of the methodology of a study on the presence of family members during CPR. If you are a doctor/and/or a nurse with experience in Emergencies or an ICU, we would be very grateful for your help. The estimated duration of this questionnaire is 4min and it is completely anonymous. Thank you very much.

Please cite this article as: Asencio-Gutiérrez JM, Reguera-Burgos I. La opinión de los profesionales sanitarios sobre la presencia de familiares durante las maniobras de resucitación cardiopulmonar. Enferm Intensiva. 2017;28:144–159.